chapter 21 Allergies

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

One problem that has so far limited our ability to successfully treat allergy is what Dr Merv Garrett of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine refers to as ‘labelling disease’.1 Allergy is a multifactorial problem, attributable to so many causal factors and appearing in so many different ways that labelling all its manifestations as allergy can mislead the practitioner into a narrow pattern of diagnosis and treatment. Any diagnosis of allergy should include a thorough investigation of the influences on that particular case, and investigation into the likely effectiveness and appropriateness of different possible treatments.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Some people, however, may have many of the symptoms of classical allergy, but reactions, which may occur hours or days after the exposure, involving little or no IgE. While these people may experience delayed skin reactions, their immediate skin reactions and blood tests for allergens may be negative or weak. More than a decade later, there is much wider recognition of the diversity of allergic responses, and of the fact that IgE-mediated responses do not account for all allergies, especially food allergies.2–4

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

It is difficult to obtain solid, consistent, up-to-date statistics on allergy, but throughout the Western world, a significant rise in the incidence of allergy has been reported since the 1950s. A report released by the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology in July 2007 stated that, ‘Allergy in the United Kingdom has now reached epidemic proportions, with new, more complex and potentially life threatening allergies’.5 Allergies are also on the rise in Australia, which has one of the highest rates in the world.

A study by the Australian Centre for Asthma Monitoring revealed that, ‘the number of Australians hospitalised for severe life-threatening allergic reactions has more than doubled in the past 15 years’, particularly among young children.6 In a lecture at the Onassis Foundation in Greece, Dr Daphne Tsitoura said that if something is not done to stem this growth, one in two Europeans will have allergies or allergy-related conditions by 2015.7

Food allergies, many of which do not fit the IgE-mediated reaction pattern, are on the rise globally. In 2001, the US Food and Drug Administration reported that ‘Only about 1.5 percent of adults and up to 6 percent of children younger than 3 years in the United States—about 4 million people—have a true food allergy, according to researchers who have examined the prevalence of food allergies’, but those statistics only included ‘classic’ allergies involving IgE. After surveying 14,948 people about seafood allergies, Sicherer and colleagues concluded that 2.3% of the general population had credible seafood allergy, suggesting that food allergies are much more prevalent than generally allowed for in US government statistics.8

The House of Lords report on allergy noted the adverse effects of allergy on quality of life, especially for children, and on school and workplace performance.5 In addition to this, allergy places an enormous economic burden on society. For these reasons alone, it is not to be taken lightly, even when the allergies are mild. Even more insidious are the less obvious and ‘hidden’ health effects of allergy. It makes life miserable for many sufferers, and has been implicated in a large number of diseases and disorders, including degenerative disease.

AETIOLOGY

OTHER PARENTAL INFLUENCES ON INFANT ALLERGY

ENVIRONMENTAL AND LIFESTYLE FACTORS

External factors can cause allergy in children and adults. In 1998, Dr Stephen Holgate wrote, in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine, ‘While ∼40% of the clinical expression of an allergic disorder can be accounted for by genetic factors, for these to be manifest there is an absolute requirement for interactions with environmental factors’.12 The World Health Organization reported that, ‘convincing evidence demonstrates that a number of environmental factors—environmental tobacco smoke, poor indoor/outdoor climate and some allergens—contribute to the onset of allergic disease. Once the disease is established, these factors may also trigger symptoms’.13

Additional factors linked to the development of allergies include:

In an article on preventing allergies, AB Becker of the University of Manitoba, Canada, wrote: ‘It is increasingly clear that gene-directed environmental manipulation of allergy in a multifaceted manner during a “window of opportunity” is critical in the primary prevention of allergy and allergic diseases like asthma’.14 The ‘window of opportunity’ for most people is in the first year of life, when a multifaceted preventive strategy can help develop the child’s resistance to allergies. Research suggests that in the first year of life, allergies may be prevented by:

THE TWO PATHWAYS TO ALLERGY

Failure of the mucous membranes

One very important example of this is ‘leaky gut syndrome’, which researchers have shown to contribute to the development of allergies.15–18 The mucous membrane lining of the gut wall can be compromised by:

DIAGNOSIS

The practitioner taking an integrative approach to allergies must be willing to look beyond the expected parameters of diagnosis, as allergies have a varied and complex pathology due to the interactions of so many different elements: physiology, psychology, genetic make-up, situation, family and environment. Not only do different people manifest the same kinds of allergies in different ways, and not only are they multifactorial in cause, but one must consider the possibility of cross-reactions, where sensitivity to one substance causes a person to be sensitive to ingredients in several other substances. For example, a person with an allergy to melons may also be allergic to other fruits or even to pollen because of certain similar ingredients. Assessment of cross-reactive food allergens requires careful history, testing and perhaps oral food challenges.19

HISTORY

Through an examination of an infant’s dietary history, for instance, it is easy to establish a relationship between severe colic and cow’s milk, from which the practitioner can surmise that the colic is associated with cow’s milk intolerance (as reported by Iacono and colleagues20 and Hill & Hosking21) without resorting to distressing skin tests, and recommend dietary treatment.

History and other investigations are critical, even when the symptoms seem to indicate one kind of allergy. Food allergies or sensitivities, for instance, can lead to lung disease, asthma, eczema, and rhinitis, wheezing and other respiratory symptoms. Asthma can show up as food allergies and gastrointestinal symptoms. Food allergy or sensitivity is, in fact, often overlooked as a cause of asthma, especially because food allergies do not always show up in standard skin tests. Multiple chemical sensitivity with its complex combination of factors can also be missed by standard tests, and is usually diagnosed by history.22

Dietary and environmental history

Exposure to toxins

Clues to environmental factors are also to be found in the patterns of presentation of symptoms, and also in chemical testing, such as hair or urinary testing to identify environmental pollutants such as arsenic or mercury.22 Because a person can be allergic to just about anything, everything with which the person comes into contact should be considered, including common household chemicals such as:

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

INVESTIGATIONS

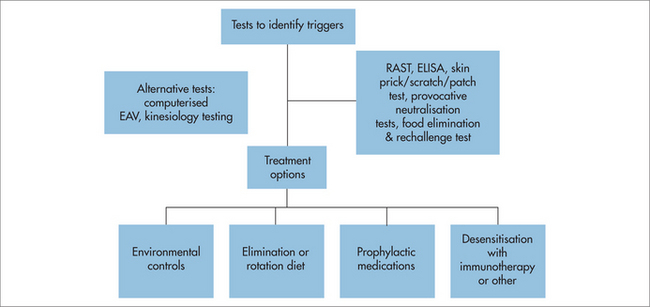

Most information will come from the history, and tests may also be administered, to identify or confirm major allergies and allow strategies to be precisely targeted. Various diagnostic procedures are available to test allergies and IgE-mediated allergies. Allopathic medicine uses various testing modalities to identify allergens and allergic reactions in sensitive individuals. Other diagnostic approaches include allergy symptom-rating questionnaire, food avoidance test, food challenge test, scratch test, elimination and challenge diet, rotation diet,23 pulse difference test,24,25 patch test, skin prick test (SPT), radioallergosorbent test (RAST), provocative neutralisation testing, immunoglobulin studies (IgE, IgA, IgM, IgG) and IgE-specific antigen studies.

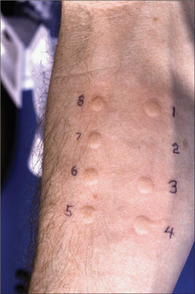

Scratch or prick test

A drop of concentrated antigen is placed on the skin, usually on the inner forearm, which is then pricked or scratched so that a minute amount of antigen is absorbed. The size of a wheal surrounded by erythema compared with the control indicates a response to a problem substance. Generally, a wheal diameter of 3 mm × 3 mm is considered positive. However, there are several complexities and pitfalls in interpreting SPTs. If a sensitive person has high IgE levels, the scratch or prick test can accurately determine allergy to pollens, moulds, dust, dust mite and animal dander. However, if IgE levels are low, a wheal may not develop even if the person tested is sensitive to these inhalants. There is no standard battery of allergens tested—the history guides which allergen extracts are used.

Blood tests

Several allergy testing methods use the person’s blood. The radioallergosorbent test (RAST) is a blood test in which IgE and IgG antibodies are labelled with a radioactive substance. The amount of antibody found in the blood in response to a given food, pollen, mould, dust and so on can be measured with a Geiger-counter type of instrument. RASTs are useful when SPTs cannot be performed. The RAST can test for sensitivities to a large number of substances in a short period of time. It works only with immunological antibodies; it cannot identify problem substances for which there is no antigen–antibody response, but it does have the advantage of measuring IgG antibodies, confirming an IgG-mediated immune response to milk in milk-intolerant individuals.26

Dietary elimination and challenge test

Elimination diet

This very reliable and effective test for food allergies was first developed by Californian Dr Albert Rowe and expounded in his book, Elimination Diets and the Patient’s Allergies (1941), and later enabled Australian researchers to establish the role played by dietary factors in certain allergies.27 Dr Rowe, formerly of the University of California School of Medicine in San Francisco, California, is considered the father of the concept of food allergy. He realised that foods can cause a problem even though the reaction is not IgE mediated. He is best known for his elimination diet, which is still important in identifying and treating food allergy.

The procedure involves two steps: elimination and reintroduction of foods.

FINAL THOUGHTS ON DIAGNOSING ALLERGIES

Inhalant allergies are often suggested by: age of onset after 18 months; anterior nasal symptoms such as itching, sneezing, clear rhinorrhoea; ticklish cough; history of asthma; and skin prick tests. They usually respond well to prophylactic drug therapy. Parents often have similar allergies. Also consider that around 20% of people with inhalant allergies also have food allergies or sensitivities. There are many cross-reactions between foods and pollens, probably because of the underlying phenolics and the homologous conserved proteins in these foods and non-food proteins.28

MANAGEMENT

PREVENTION

The first major challenge in treating allergies is to change the emphasis from drug treatment to prevention. Prevention is rarely funded, but it is the best approach to ward off the development of allergies, chronic disease and morbidity. The most effective preventive strategies are those targeting the newborn and small child, but the onset of allergies can occur at any time of life. Therefore, the preventive strategies below include some that are also relevant to adults.

Modified maternal diet during pregnancy and breastfeeding

An allergic mother should eliminate common allergenic foods and foods to which she is allergic from her diet before (if possible) and during pregnancy, to eliminate common allergens. The Allergy Unit of the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney reported that children whose mothers eliminated allergenic foods from their diet had at least 50% fewer allergies than children whose mothers did not modify their diet, and that ‘there were fewer problems with egg, milk, and peanut allergies’.29 Citrus, kiwifruit, large fish, soy, legumes and wheat should also be avoided.

Delayed vaccinations

Some researchers have raised concerns about possible effects of early vaccinations on the child’s immature immune system.30,31 The general consensus, however, is that the protective benefits of vaccines outweigh the possible risks. Vaccination induces a predominately Th2-mediated immune response and probiotics may be beneficial during routine vaccinations, to manage the effects of vaccinations in children.

Promotion of beneficial intestinal microflora

Beneficial intestinal microflora help protect against damage to the digestive tract, reverse intestinal permeability and reduce antigen load in the gut by degrading and modifying potentially harmful macromolecules. A maternal probiotic supplement is suggested during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and also for the baby from birth, and in the event of antibiotic treatment. Antibiotics can disrupt the balance of intestinal bacteria, allowing pathogens to proliferate, which has been shown to cause allergies.32,33 Research into the effects of intestinal microflora on allergy indicated that infants with greater diversity of microbial colonisation by 1 month of age were less likely to develop allergies.33

PLANNING THE INTEGRATIVE STRATEGY

To understand the clinical patterns of allergies, you need to ask some critical questions:

The answers to these questions will assist in planning treatment strategies. While different doctors may respond to this information by selecting different methods and resources, a multi-track strategy is the only way to address the complexity of factors associated with allergy, and to provide a holistic healing framework for each patient. Some of the many possible treatment options that different practitioners and patients have reported to be effective are described in the following sections.

KEY ELEMENTS OF AN INTEGRATIVE APPROACH TO TREATING ALLERGIES

Nutritional support

Supplements—because allergies often deplete the body of certain nutrients, supplements may also be required, including vitamin C to reduce atopy in infants,34 essential fatty acids, minerals and vitamin E. Consumption of sugar and unhealthy fats should be reduced, as they impair immunity.

Avoidance of allergens

Exposure to allergens has been shown to set off allergies,35 and some people with multiple chemical sensitivities (acute hypersensitivity to low levels of everyday chemicals) can begin reacting to more and more specific environmental chemicals found in the workplace, school or home as their allergies spread.36 Avoidance and clearing the home of known contact and inhalant allergens is especially recommended for high-risk children or adults, and for those with a weakened immune system. Avoidance is an essential component of treatment as it allows the person’s system to become clear of allergens and recover from the effects of reactions, many of which do not show up as symptoms. Pay particular attention to substances that are known to commonly cause allergies, such as dust mites, pesticides and household chemicals.

Promotion of intestinal microflora

TREATMENT

PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENTS

Antihistamines work by blocking histamine from H1 receptors, and are used for relief and to prevent symptoms when exposure to allergens is unavoidable. They are delivered as nasal sprays, eye drops, oral tablets and topical creams and sprays. Decongestants work by reducing swelling of mucous membranes and blood vessels. It is recommended that topical decongestants, if used at all, not be used for more than 3–5 days, to avoid a rebound nasal reaction. Systemic decongestants can be used for longer periods of time. However, stimulant side effects require care for people with high blood pressure or heart disease.

Immunotherapy

This treatment uses serums containing extracts of allergens to stimulate the immune system with gradually increasing doses of the substances to which a patient is allergic, with the aim of weakening or ending the allergic response. It has been found most effective for IgE-mediated inhalant sensitivities such as persistent allergic rhinitis, which puts patients at risk of developing asthma,37 especially for allergies to dust mites, pollens, animal dander and insect bites. Immunotherapy can take 6–12 months to become effective, with injections required every few years thereafter. Immunotherapy may be suggested for those whose response to drugs has been poor, and when the allergen cannot be avoided. Contraindications are beta-blockers, autoimmune disease, other serious conditions, pregnancy, multiple allergies and lymphoproliferative disorders.1

Management of anaphylaxis

Prepare for an emergency

A comprehensive emergency strategy might include the following steps:

COMPLEMENTARY OR ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES FOR ALLERGY

Enzyme-potentiated desensitisation

Developed in the 1960s by British immunologist Dr Leonard McEwen, enzyme-potentiated desensitisation (EPD) is used to train the patient’s immune system to not react to allergens. Like other forms of immunotherapy, it uses extracts of allergens, but with three significant differences: the dilutions are even weaker than is usually used; extracts of multiple related allergens are used in each serum; and the serum also contains an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme, which is used at a similar strength to that at which it occurs in the body, makes the vaccine more potent. The serum is believed to activate suppressor T-cells. Once these are activated, injections are spaced weeks or months apart.

Allergy information sheets, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney. http://www.sswahs.nsw.gov.au/rpa/allergy/default.htm.

Auckland Allergy Clinic, food cross-reactions. http://www.allergyclinic.co.nz/guides/42.html.

Food Intolerance Network. http://www.fedupwithfoodadditives.info/.

Health Professional Information, Australasian Society Clinical Immunology and Allergy, ASCIA Education Resources. http://www.allergy.org.au/content/view/139/114/.

National Asthma Council Australia. http://www.nationalasthma.org.au/content/view/176/25/.

Victorian Department of Health, Better Health Channel. Food allergy and intolerance. http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/Food_allergy_and_intolerance/.

Debarry J, Garn H, Hanuszkiewicz A, et al. Acinetobacter lwoffii and Lactococcus lactis strains isolated from farm cowsheds possess strong allergy-protective properties. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1514-1521.

Eaton KK, Howard M, Howard JM. Princess Margaret Hospital, Windsor, Berkshire, UK. Gut permeability measured by polyethylene glycol absorption in abnormal gut fermentation as compared with food intolerance. J R Soc Med. 1995;88(2):63-66.

Formanek Jr R. Food allergies: when food becomes the enemy. FDA Consumer magazine 2001; July/August:10–16. Pub No. FDA 04-1312C

Kemp AS, Mullins RJ, Weiner JM. The allergy epidemic: what is the Australian response? Med J Aust. 2006;185(4):226-227.

Law M, Morris J, Wald N, et al. Changes in atopy over a quarter of a century, based on cross-sectional data at three time periods. Br Med J. 2005;330:1187-1188.

Mrazek DA, Schuman WB, Klinnert M. Early asthma onset: risk of emotional and behavioral difficulties. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39:247-254.

Nsouli TM, Nsouli SM, Linde RE, et al. Role of food allergy in serous otitis media. Ann Allergy. 1994;73(3):215-219.

Ouwehand A, Kirjavainen P, Laiho K, et al. From hypoallergenic foods to anti-allergenic foods. Food Science & Technology Bulletin: Functional Foods. 2003;1(5):1-12.

Pelto L, Isolauri E, Lilius E-M, et al. Probiotic bacteria down-regulate the milk-induced inflammatory response in milk-hypersensitive subjects but have an immunostimulatory effect in healthy subjects. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28:1474-1479.

Prescott SL, Tang M. ASCIA Position Statement: Summary of Allergy Prevention in Children, as published in the Medical. Journal of Australia. 2005;182(9):464-467. Online. Available: http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/182_09_020505/pre10874_fm.html.

Rapp DJ. Allergies and your family. New York: Sterling, 1984.

Randolph T. Environmental medicine: beginnings and biographies of clinical ecology. Fort Collins, CO: Clinical Ecology Publications, 1987.

Rea WJ. Chemical sensitivity, Vols 1–4. Boca Raton, FL: Lewis, 1992–97.

Reynolds G. Food allergies rise 12-fold in Australian children. AP-FoodTechnology.com; 2007. Online. Available: http://www.ap-foodtechnology.com/news/ng.asp?id=77467 19 October 2007.

Sampson HA. Food allergy. JAMA. 1997;278(22):1888-1894.

Sampson H, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell R, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Aller Clin Immunol. 2005;117(2):391-397.

Simpson A, Custovic A. Pets and the development of allergic sensitization. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005;5(3):212-220.

Tamburlini G, von Ehrenstein O, Bertolini R, editors. Children’s health and environment: a review of evidence: a joint report from the European Environment Agency and the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency; 2002:48-49. Environmental Issue Report No. 29.

Taylor F, Krohn J. Allergy relief and prevention. A practical encyclopedia. A doctor’s complete guide to treatment and self care. 3rd edn. Vancouver: Hartley & Marks, 2000.

Wright RJ. Stress and atopic disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;116(6):1301-1306.

1 Garrett M. Allergy in general practice. Paper presented at the Gold Coast Allergy and Sensitivity Specialist Training Program, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, 16–17 July 2005.

2 Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Simon D, Simon H, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and immunology of the ‘intrinsic’ (non-IgE-mediated) type of atopic dermatitis (constitutional dermatitis). Allergy. 2001;56(9):841-849.

3 Sabra A, Bellanti J, Rais JM, et al. IgE and non-IgE food allergy. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(6 Suppl 1):71-76.

4 Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2):540-547.

5 House of Lords Science and Technology Committee. Allergy, Volume 1: Report. 26 September 2007. London: House of Lords, 2007;6.

6 The Age, 12 October 2007. Severe allergic reactions on the rise. Online. Available: http://www.theage.com.au/news/NATIONAL/Severe-allergic-reactions-on-the-rise/2007/10/12/1191696150293.html.

7 Tsitoura D. Allergy: a novel epidemic in the developed world of 21st century. AΩ International Online Magazine 2007; March (5). Online. Available: http://www.onassis.gr/enim_deltio/foreign/05/story_04.php.

8 Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of seafood allergy in the United States determined by a random telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(1):159-165.

9 Klinnert MD, Nelson HS, Price MR, et al. Onset and persistence of childhood asthma: predictors from infancy. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):69.

10 American Thoracic Society. Mother’s prenatal stress predisposes their babies to asthma and allergy, study shows. Science Daily. Online. Available: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/05/080518122143.htm, 19 May 2008.

11 Wright RJ. Stress and atopic disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;116(6):1301-1306.

12 Holgate ST. Asthma and allergy—disorders of civilization? Q J Med. 1998;91:171-184.

13 World Health Organization. Environmental hazards trigger childhood allergic disorders. 1 Fact sheet EURO/01/03 Copenhagen, Bonn, Brussels, Moscow, Oslo, Rome, Stockholm, 4 April 2003, p. 2. Online. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/document/mediacentre/fswhde.pdf.

14 Becker AB. Primary prevention of allergy and asthma is possible. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28(1):5-16.

15 Cereijido M, Contreras RG, Flores-Benitez D, et al. New diseases derived or associated with the tight junction. Arch Med Res. 2007;38(5):465-478.

16 Kirjavainen PV, Apostolou E, Arvola T, et al. Characterizing the composition of intestinal microflora as a prospective treatment target in infant allergic disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2001;32(1):1-7.

17 Liu Z, Li N, Neu J. Tight junctions, leaky intestines, and pediatric diseases. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(4):386-393.

18 Taylor L, Hale J, Wiltschut J, et al. Effects of probiotic supplementation for the first 6 months of life on allergen- and vaccine-specific immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36(10):1227-1235.

19 Auckland Allergy Clinic. Oral (provocation) challenges. Online. Available: http://www.allergyclinic.co.nz/guides/68.html, 2005.

20 Iacono G, Carroccio A, Montalto G, et al. Severe infantile colic and food intolerance: a long-term prospective study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:332-335.

21 Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Infantile colic and food hypersensitivity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(1 Suppl):67-76.

22 Hromek K. Taking a dietary/environmental history. Paper presented at the Gold Coast Allergy and Sensitivity Specialist Training Program, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, 16–17 July 2005.

23 Randolph TG, Rinkel H, Zeller M. Food allergy. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1951.

24 Coca A. Familial nonreagenic food allergy. Springfield; 1942.

25 Coca A. The pulse test. New York: Lyle Stewart, 1956.

26 Little CH, Georgiou GM, Shelton MJ, et al. Production of serum immunoglobulins and T-cell antigen binding molecules specific for cow’s milk antigens in adults intolerant to cow’s milk. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;89(2):160-170.

27 Gibson A, Clancy R. Management of chronic idiopathic urticaria by the identification and exclusion of dietary factors. Clin Allergy. 1980;10(6):699-704.

28 Garrett M. Inhalent allergy. Paper presented at the Gold Coast Allergy and Sensitivity Specialist Training Program, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, 16–17 July 2005.

29 Soutter V, Swain A, Loblay R. Food allergy prevention. Sydney: Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; 2002. Online. Available: http://www.cs.nsw.gov.au/rpa/allergy/resources/allergy/prevention.pdf.

30 Hurwitz E, Morgenstern H. Effects of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis or tetanus vaccination on allergies and allergy-related respiratory symptoms among children and adolescents in the United States. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:81-90. Abstract available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10714532.

31 Sakaguchi M, Inouye S. IgE sensitization to gelatin: the probable role of gelatin-containing diphtheria–tetanus–acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccines. Vaccine. 2000;18(19):2055-2058.

32 Noverr M, Noggle RM, Toews GB, et al. Role of antibiotics and fungal microbiota in driving pulmonary allergic responses. Infect Immun. 2004;72(9):4996-5003. Abstract. Online. Available: http://iai.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/70/1/400.

33 Wold A, Strachan D, Matricardi P, et al. Impact of intestinal microflora on allergy development (Allergyflora). Online. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/research/quality-of-life/ka4/pdf/report_allergyflora_en.pdf, 2005. 20 October 2007.

34 Hoppu U, Rinne M, Salo-Väänänen P, et al. Vitamin C in breast milk may reduce the risk of atopy in the infant. Abstract. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(1):123-128.

35 Sporik R, Holgate ST, Platts-Mills TAE, et al. Exposure to house dust mite allergen (DerP1) and the development of asthma in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:502-507.

36 Beresford P. Report on Environmental Hypersensitivity in response to the Report of the Advisory Committee to the Minister of Health, Province of Nova Scotia. Online. Available: http://www.environmentalhealth.ca/Jan98report.html, 5 January 1998.

37 Marogna M, Falagiani P, Bruno M, et al. The allergic march in pollinosis: natural history and therapeutic implications. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;135(4):336-342. Abstract. Online. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15564776.