Chapter 137 Allergic Rhinitis

Differential Diagnosis

Evaluation of AR calls for a thorough history, including details of the patient’s environment and diet and family history of allergic conditions such as eczema, asthma, and AR, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation. The history and laboratory findings provide clues to the provoking factors. Symptoms that include sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal itching, and congestion and the laboratory findings of elevated IgE, specific IgE antibodies, and positive allergy skin test results typify AR. SAR differs from PAR by history and skin test results. Nonallergic rhinitides cause sporadic symptoms and may resemble PAR. Their causes are often unknown. Nonallergic inflammatory rhinitis with eosinophils (NARES) imitates AR in presentation and response to treatment, but without elevated IgE antibodies. Vasomotor rhinitis is characterized by excessive responsiveness of the nasal mucosa to physical stimuli. Other nonallergic conditions, such as infectious rhinitis, structural problems including nasal polyps and septal deviation, rhinitis medicamentosa (due to the overuse of topical vasoconstrictors), hormonal rhinitis associated with pregnancy or hypothyroidism, neoplasms, vasculitides, and granulomatous disorders may mimic AR (Table 137-1).

Complications

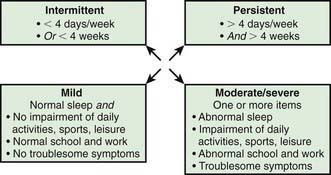

Quality of life indices have been developed to explore the effects of the disease and of therapeutic interventions. The Pediatric Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (PRQLQ) is suitable for children from 6 to 12 yr old, and the Adolescent RQLQ is appropriate for patients between 12 and 17. Studies using the PRQLQ in children with rhinitis have documented anxiety and physical, social, and emotional issues that affect learning and the ability to integrate with peers. The disorder contributes to headaches and fatigue, limits daily activities, and interferes with sleep. There is evidence of impaired cognitive functioning and learning that may be further threatened by the adverse effects of sedating medications. Rhinitis is an important cause of lost school attendance, resulting in more than 2 million absent days in the United States annually. A classification based on severity is shown in Figure 137-1.

Treatment

The direct costs of allergic rhinitis have increased substantially since the introduction of second-generation antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids (Tables 137-2 through 137-4). Oral antihistamines administered as needed constitute acceptable pharmacotherapy of mild, intermittent symptoms; however, first- and second-generation antihistamines available over the counter (OTC) may be associated with adverse effects on cognitive function and learning as a result of their sedative properties. Antihistamines relieve sneezing and rhinorrhea. Second-generation antihistamines are preferred because they cause less sedation. Five second-generation oral preparations are currently available:

| DRUG AND TRADE NAME(S) | INDICATIONS (I), MECHANISM OF ACTION (M), AND DOSING* | COMMENTS, CAUTIONS, AND ADVERSE EVENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Diphenhydramine (OTC): |

OTC, available over the counter (nonprescription); Rx, prescription required.

* All of these agents are administered orally.

Table 137-3 INTRANASAL INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS

| DRUG, TRADE NAME(S), AND FORMULATIONS | INDICATIONS (I), MECHANISM(S) OF ACTION (M), AND DOSING | COMMENTS, CAUTIONS, ADVERSE EVENTS, AND MONITORING |

|---|---|---|

| Beclomethasone: | ||

| Beconase AQ (42 µg/spray) | ||

| Flunisolide | ||

| Nasarel (25 µg/spray) | ≥6 yr: initial dose 1 spray tid or 2 sprays in each nostril bid; reduce to lowest effective dose | |

| Triamcinolone: | ||

| Nasacort HFA (55 µg/spray), Nasacort AQ (55 µg/spray) | ||

| Fluticasone: |

Ritonavir significantly increases fluticasone serum concentrations and may result in systemic corticosteroid effects.

|

|

| Fluticasone propionate (available as a generic preparation): | ||

| Flonase (50 µg/spray) | ≥4 yr: 1-2 sprays in each nostril qd | |

| Fluticasone furoate: | ||

| Veramyst (27.5 µg/spray) | ||

| Mometasone: | ||

| Nasonex (50 µg/spray) | ||

| Budesonide: | ||

| Rhinocort AQ (32 µg/spray) | ||

| Ciclesonide: | ||

| Omnaris (50 µg/spray) | >6 yr: 2 sprays in each nostril qd |

Table 137-4 MISCELLANEOUS INTRANASAL SPRAYS

| DRUG, TRADE NAME(S), AND FORMULATIONS | INDICATIONS (I), MECHANISM(S) OF ACTION (M), AND DOSING | COMMENTS, CAUTIONS, ADVERSE EVENTS, AND MONITORING |

|---|---|---|

| Ipratropium bromide: | ||

| Atrovent nasal spray (0.06%) | ||

| Azelastine: | ||

| Astelin | ||

| Cromolyn sodium: | Not effective immediately; requires frequent administration. | |

| Nasalcrom | >2 yr: 1 spray tid-qid; max 6 ×/day | |

| Oxymetazoline: | ||

| Afrin, Nōstrilla | 0.05% solution: Instill 2-3 sprays into each nostril twice daily; therapy should not exceed 3 days | |

| Phenylephrine: | ||

| Neo-Synephrine |

2-6 yr: 1 drop every 2-4 hr of 0.125% solution as needed. Note: Therapy should not exceed 3 continuous days.

|

Akdis CA. New insights into mechanisms of immunoregulation in 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:700-709.

Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008;63(Suppl 86):8-160.

De Groot H, Brand PL, Fokkens WF, et al. Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children. BMJ. 2007;335:985-988.

Howath PH, Myginf N, Silkoff PE, et al. Preface to outcome measures in allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:S387-S482.

Nelson HS. Allergen immunotherapy: where is it now? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:769-779.

Radulovic S, Calderon MA, Wilson D, et al: Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12)CD002893, 2010.

Simoens S, Laekeman G. Pharmacotherapy of allergic rhinitis: a pharmaco-economic approach. Allergy. 2009;64:85-95.

Wahn W, Taber A, Kuna P, et al. Efficacy and safety of 5-grass-pollen sublingual immunotherapy tablets in pediatric allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:160-166.

Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:S1-S84.

Weinstein S, Qaqundah P, Georges G, et al. Efficacy and safety of triamcinolone acetonide aqueous nasal spray in children aged 2 to 5 yr with perennial allergic rhinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with an open label extension. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:339-347.

Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Martinez FD, et al. Epidemiology of physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis in childhood. Pediatrics. 1994;94:895-901.