5 Allergic Eye Diseases, Episcleritis and Scleritis

ALLERGIC EYE DISEASE

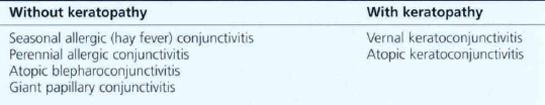

Allergic eye disease in its various forms is a common cause of ocular morbidity in both primary care and specialist practice. The external eye is under constant immunological challenge from a wide variety of substances; this may lead to the development of one of many conditions that can be loosely grouped as ‘allergic eye disease’. The chief factors determining the outcome of such challenges are the severity and duration of the antigenic load and the immunological status of the individual. Local or systemic immune mechanisms may be involved to produce immediate hypersensitivity, complement-mediated or delayed hypersensitivity reactions. The spectrum of allergic conjunctivitis (Table 5.1) ranges from mild self-limiting seasonal conjunctivitis to atopic keratoconjunctivis in which vision is threatened by corneal vascularization, herpetic epithelial infection and the long-term complications of topical corticosteroid therapy. Although patients complain of red, sore and discharging eyes, itchiness is the characteristic symptom of allergic eye disease. Patients also have an increased risk of keratoconus and atopic cataract. Increased levels of IgE and eosinophils are found in the conjunctiva and a wide range of inflammatory mediators have been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis.

IMMEDIATE HYPERSENSITIVITY REACTIONS

Fig. 5.1 Acute periorbital oedema is a common manifestation of immediate hypersensitivity and appears within minutes of exposure. It may follow the systemic administration of antigen in a sensitized individual such as the ingestion of foods or drugs. The reaction is frequently associated with high titres of circulating IgE antibody, being mediated by the release of histamine and other pharmacologically active substances from mast cells in the skin and mucosal tissues. It usually produces symmetrical bilateral lid oedema which may also be accompanied by conjunctival chemosis and urticarial skin rashes. The onset is rapid but the signs usually improve within a few hours. Acute unilateral signs may result from local inoculation and histamine release in the skin, as in this patient where the reaction followed an insect bite.

Fig. 5.2 Acute conjunctival chemosis may occur in the absence of lid swelling as an immediate hypersensitivity response to local inoculation of antigenic substances (frequently pollens) directly on to the conjunctiva of a sensitized individual. The level of response depends on the degree of previous sensitization and the dose of antigen. In this patient, although both conjunctiva are chemotic and slightly hyperaemic, the signs are more pronounced in the left eye.

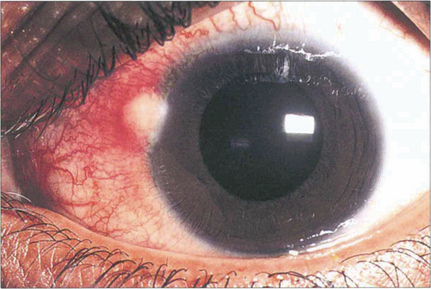

Fig. 5.3 Phlyctens are inflammatory nodules usually seen on the nasal limbus with an associated hyperaemia. They are bilateral and are usually seen in children and young adults. Phlyctens represent a lymphocyte cell-mediated response in a previously sensitized individual. They are associated with a variety of antigens; staphlococci are now the commonest cause, but in the past the main cause was tuberculosis.

ALLERGIC CONJUNCTIVITIS

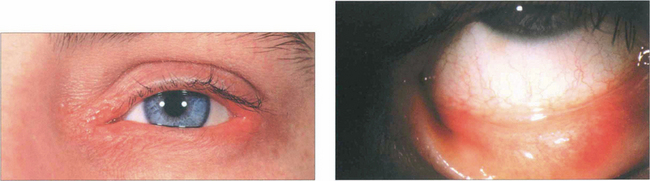

Fig. 5.4 Atopic blepharoconjunctivitis is typified by thickening of eyelid and periocular skin. Conjunctival inflammation is moderate and keratopathy is absent.

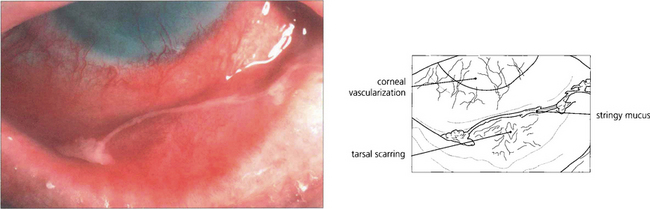

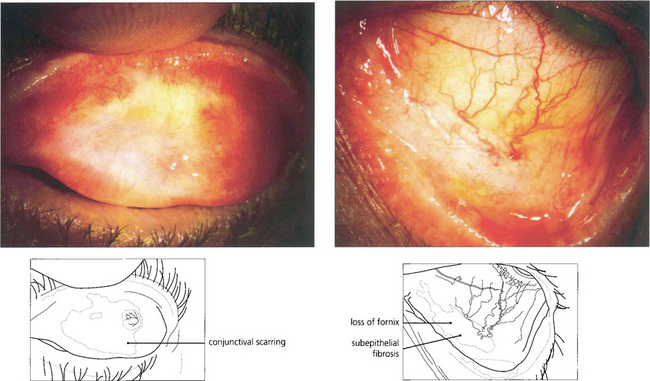

Fig. 5.5 Atopic keratoconjunctivitis is uncommon and is usually seen in young men with atopic dermatitis and a history of childhood eczema. The ocular changes are seen in early adult life; they are bilateral, symmetrical and persistent for many years. The conjunctival changes carry a significant risk of sight-threatening complications which include corneal vascularization, herpes simplex viral keratitis and steroid-induced glaucoma. Cicatrizing conjunctivitis and fornix shortening results from progressive subepithelial scarring.

VERNAL KERATOCONJUNCTIVITIS

Fig. 5.6 This boy, who suffers from VKC, shows a typical eczematous rash on his forehead and cheeks. There is an associated slight bilateral ptosis reflecting the chronic inflammation on the upper tarsal conjunctiva.

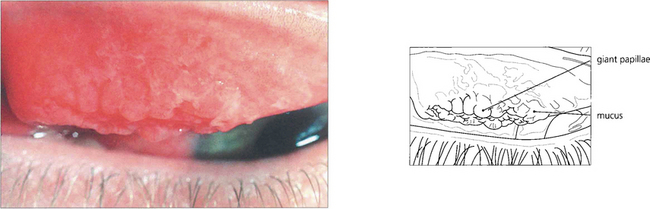

Fig. 5.7 Giant papillae on the upper tarsus, typically described as having a ‘cobblestone’ appearance, are the hallmark of VKC. Although these papillae persist during quiescent phases they become swollen and infiltrated by oedema and inflammatory cells with abundant abnormal mucus both on the surface and in the crevices between the papillae when the disease becomes active, as in this example.

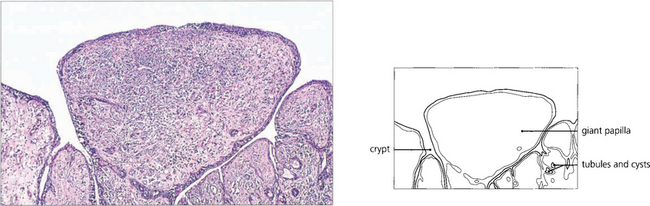

Fig. 5.9 A histological section of VKC shows typical papillae with epithelial downgrowth to form tubules and cysts. The papillae have a loose stroma in which inflammatory cells are seen. Eosinophils and basophils are present in large numbers during the active phase of the disease.

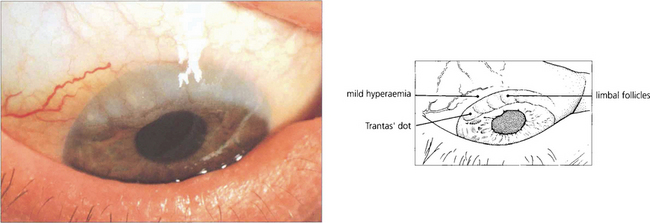

Fig. 5.10 Limbal follicles may occur in VKC and are seen more commonly in black patients in the absence of marked tarsal papillae. This is sometimes known as the ‘limbal’ form of the disease. These limbal lesions are heavily infiltrated with inflammatory cells and appear as greyish, gelatinous swellings, especially around the superior limbus. The blood vessels are not unduly prominent and no mucus is visible.

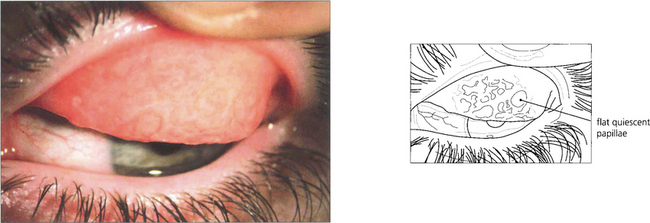

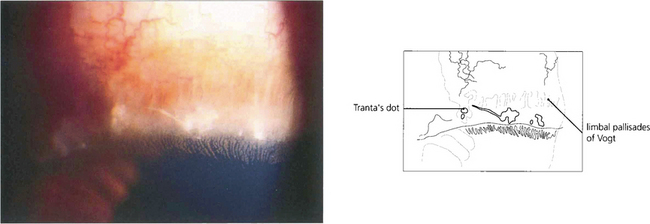

Fig. 5.11 Trantas’ dots are a feature of VKC. They are small, white, elevated, epithelial lesions seen on the limbal lesions at the superior limbus and contain eosinophils. In this example they are associated with a greyish corneal infiltrate.

By courtesy of Professor R J Buckley.

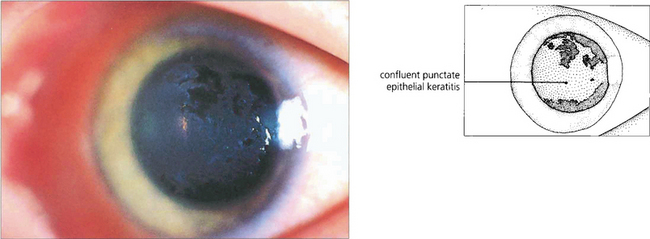

Fig. 5.12 This patient illustrates the early corneal changes seen in vernal disease. There is a fine punctate epithelial keratopathy consisting of fine grey dots which has become confluent in some areas. Eosinophilic major basic protein from disrupted eosinophils is cytotoxic and thought to play a major role in vernal keratopathy.

By courtesy of Professor R J Buckley.

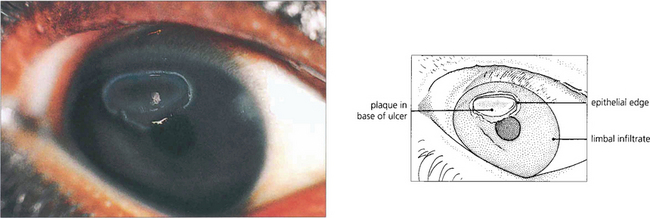

Fig. 5.13 A vernal ulcer characteristically develops in the upper half of the cornea during active phases of tarsal disease and is shown here stained with fluorescein. The edge of the ulcer is surrounded by whitish, heaped-up epithelium. The base is composed of abnormal mucus that is deposited with fibrin and other serum constituents as a grey plaque. When established, this plaque prevents healing from occurring. An area of superficial corneal infiltration can be seen nearer the limbus on the nasal side of the cornea.

By courtesy of Professor R J Buckley.

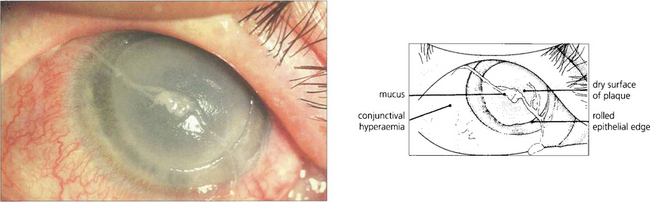

Fig. 5.14 This is a more severe example of a vernal ulcer showing a large area of central ulceration with established plaque formation. This image illustrates the nonwetting properties of the plaque and the raised epithelial edge, which is indicative of poor healing in the presence of plaque. Peripheral to the ulcer, the cornea is relatively clear although corneal vascularization from the limbus has commenced. The conjunctiva is hyperaemic and a strand of typically ‘stringy’ mucus lies on the surface of the eye.

GIANT PAPILLARY CONJUNCTIVITIS

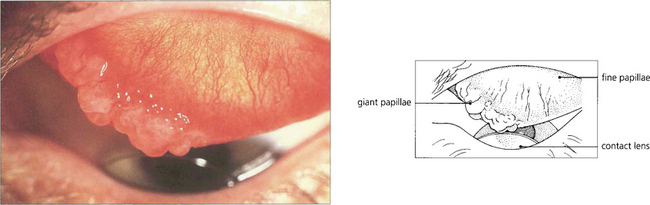

Fig. 5.15 Giant papillary conjunctivitis is a chronic condition affecting the upper tarsal conjunctiva; it is caused by mechanical irritation. The condition is seen, for example, in patients wearing contact lenses, ocular prostheses or in association with protruding nylon suture ends following corneal or cataract surgery. Patients complain of itching, ocular discomfort and a stringy discharge. The aetiology appears to be mast cell degranulation initiated by mechanical trauma. In this example, a hard contact lens has produced giant papillae at the medial end of the upper border of the tarsus with a fine papillary reaction elsewhere. The condition is clinically distinguishable from vernal conjunctivitis by the lack of changes elsewhere in the conjunctiva, absence of an atopic history, and the presence of an associated foreign body. The conjunctival changes resolve with removal of the irritating stimulus.

OCULOCUTANEOUS CICATRICIAL DISORDERS

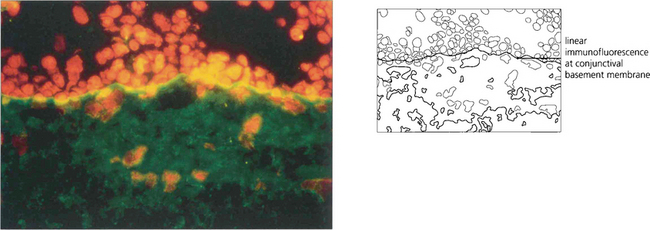

OCULAR CICATRICIAL PEMPHIGOID

Fig. 5.16 Ulceration of the conjunctiva in active mucous membrane pemphigoid is clearly delineated in this case following instillation of fluorescein.

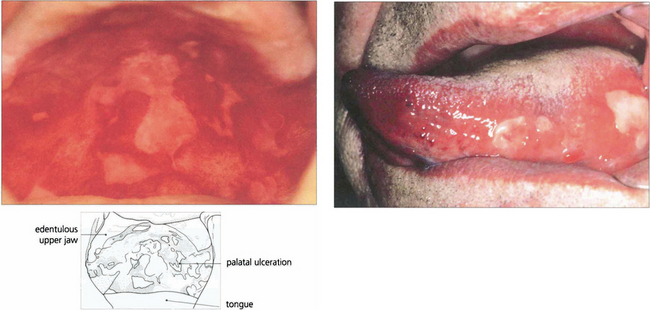

Fig. 5.17 Extensive palatal ulceration is visible in this edentulous patient (left). The painful mouth ulcers had been erroneously attributed by the patient to poorly fitting dentures. Buccal mucous membrane pemphigoid (right) is also characterized by tongue involvement, as in this patient in whom blisters are seen alongside sloughing ulcers, which indicate the site of a previous blister.

By courtesy of Dr F M Tatnall.

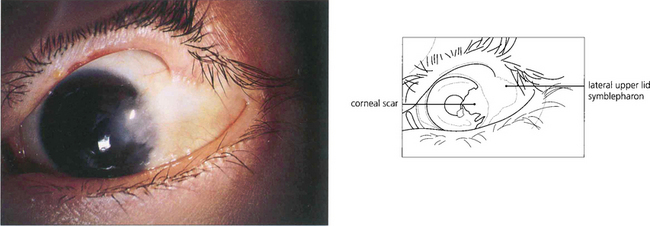

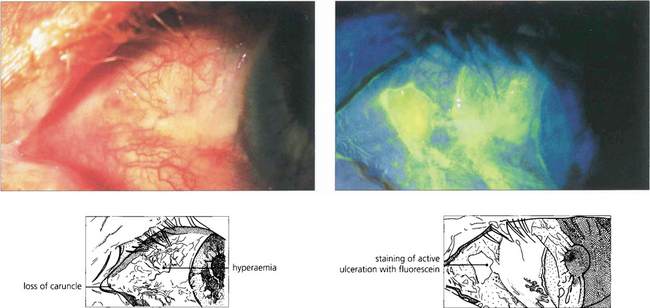

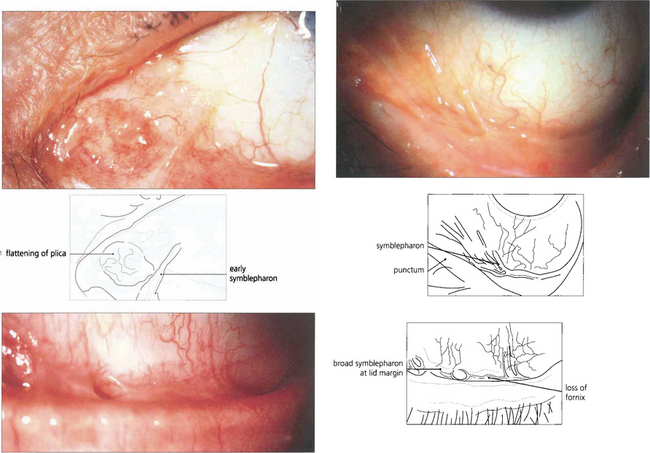

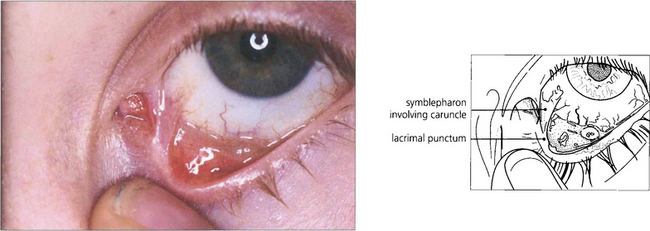

Fig. 5.18 In early pemphigoid, conjunctival cicatrization usually obliterates the caruncle (top left), producing progressive loss of the fornices and symblepharon formation. This example (top right) shows symblepharon formation in early disease which has been arrested by therapy. Inexorable progression to late disease is associated with scarring that almost obliterates the inferior fornix (bottom left).

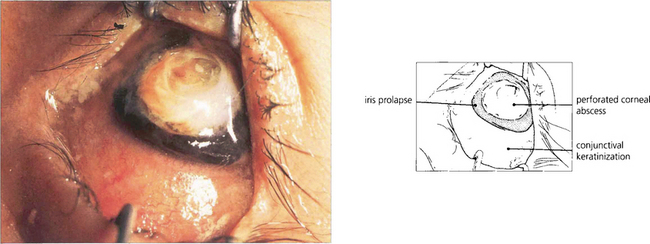

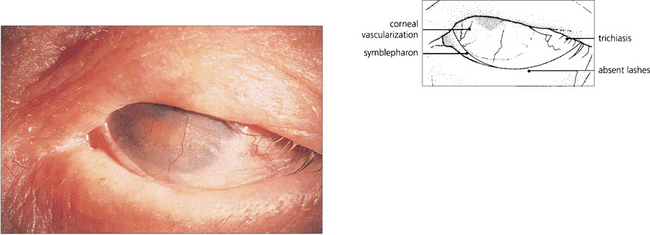

Fig. 5.19 This example illustrates a late stage of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid with gross symblepharon formation, corneal scarring and vascularization resulting from corneal drying. This is associated with loss of tears and mucus-producing cells in the conjunctiva. The lashes have been removed during the course of the disease to prevent further corneal trauma from trichiasis and cicatricial entropion.

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Fig. 5.21 The rash of erythema multiforme starts on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, and spreads to involve the trunk. The skin lesions consist of an area of erythema surrounding a paler centre, which may ulcerate to give a ‘target’ appearance. The lesions heal without scarring.

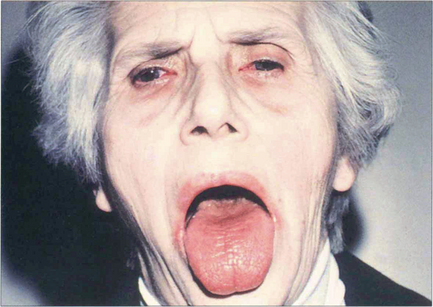

Fig. 5.22 In its more severe form, with mucous membrane involvement, erythema multiforme is known as Stevens–Johnson syndrome. This patient shows extensive oral ulceration involving the upper and lower lips. Patients are acutely ill, losing serum and protein through their skin; they are unable to eat and at grave risk of secondary infection. Systemic steroids, fluid replacement and prophylactic antibiotics are the basis of treatment.

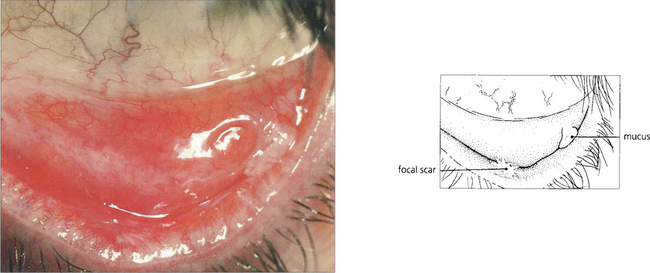

Fig. 5.23 Stevens–Johnson syndrome produces focal ulcerative changes in the conjunctiva where a severe pseudomembranous conjunctivitis may also occur in the acute stages. In the resolving phase healing is accompanied by scar formation which is typically focal, as seen here on the lower tarsus. The ocular surface is affected as a secondary phenomenon due to tear film changes.

Fig. 5.24 Symblepharon formation is a frequent result of conjunctival involvement in erythema multiforme. In this example a fibrous band is seen at the medial canthus, stretching from the lower punctum across to the bulbar conjunctiva. These symblephara are narrow, in contrast to the broad bands of ocular pemphigoid.

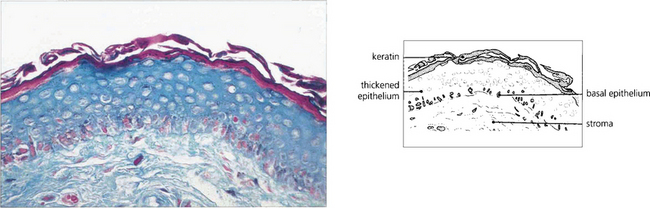

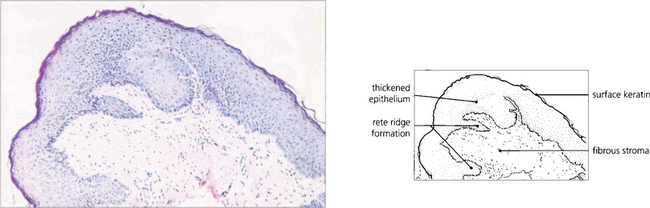

Fig. 5.25 Histological changes in end-stage erythema multiforme may be similar to those seen in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Patchy epidermidalization of the conjunctiva has taken place as evidenced by rete ridge formation, thickened epithelium with a prickle cell layer, and keratin formation giving the histological appearance of skin without hair follicles or other appendages. The underlying stroma shows marked fibrosis. In the acute phase of the disorder a mononuclear cell infiltrate in the stroma would be characteristic.

GRAFT VERSUS HOST DISEASE

Fig. 5.26 This patient developed GVH disease that was treated successfully by immunosuppressive therapy 12 months after bone marrow transplantation. The scarring on the upper tarsus shown in this picture has persisted unchanged for 10 years, punctal occlusion and intensive artificial tear supplements were required to maintain the corneal surface.

OCULAR SURFACE DISORDERS

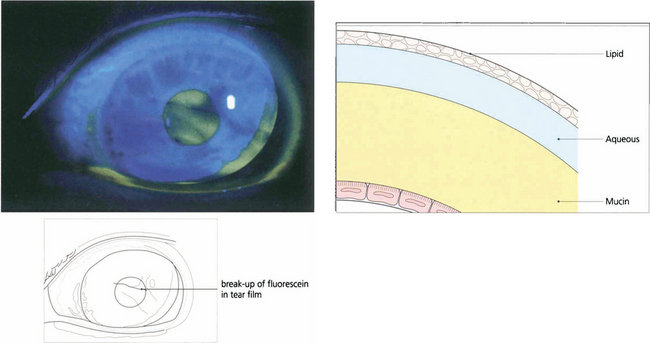

Fig. 5.29 The adequacy of the precorneal tear film may be judged qualitatively by the presence of excess debris or mucus, a decrease in the marginal tear meniscus and a shortened break-up time of the fluorescein-stained tear film.

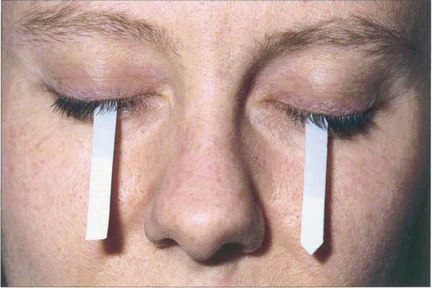

Fig. 5.30 Schirmer’s test is useful in documenting tear production, although the results cannot always be correlated to symptoms. In the absence of local anaesthesia, a normal value is greater than 6 mm at 5 min.

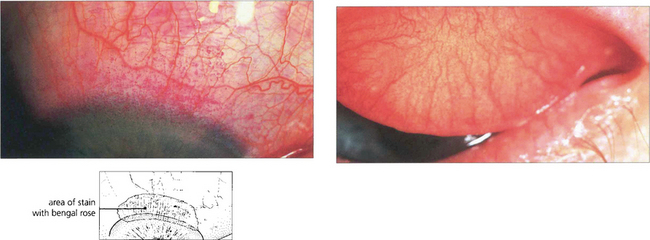

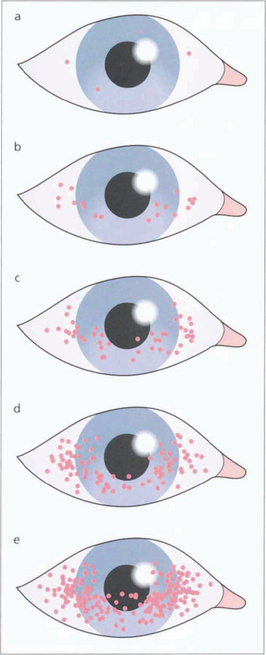

Fig. 5.31 Dessicated epithelium stains with Bengal Rose dye; the degree of staining can be used to grade the severity of epithelial disturbance on the medial and lateral conjunctiva and cornea.

Adapted from A J Bron, Doyne Lecture. Reflections on the tears. 1997; 11:583–602.

KERATOCONJUNCTIVITIS SICCA

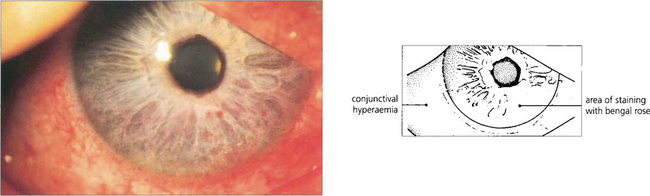

Fig. 5.32 The clinical picture of keratoconjunctivitis sicca shows diffuse punctate epithelial erosions over the lower one-third of the corneal epithelium that stain as red spots with Bengal Rose. The staining usually extends on to the lower bulbar conjunctiva in the exposure area. In this patient there is some associated conjunctival hyperaemia.

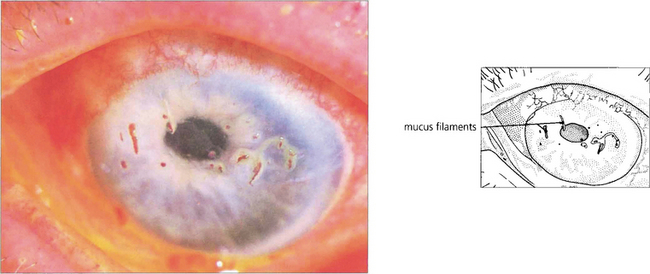

Fig. 5.33 In severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca, threads of dried mucus and epithelial cell debris become attached to the corneal epithelium. This condition is known as filamentary keratitis. Bengal rose stains mucus and devitalized cells; in this example it is seen staining the filaments more avidly than fluorescein, which has also been instilled. Filamentary keratitis produces severe discomfort and photophobia. Treatment lies in tear film augmentation and topical mucolytic agents.

By courtesy of Professor R J Buckley.

Fig. 5.34 The commonest association of keratoconjunctivitis sicca is rheumatoid arthritis. Among sufferers of the disease, 15 per cent may be expected to develop dry eyes, although usually not severely. This example shows the changes associated with advanced rheumatoid arthritis of the hands including the swollen metacarpophalangeal joints, ulnar deviation, swan-neck deformities of the fingers and the skin changes associated with vasculitis and steroid therapy.

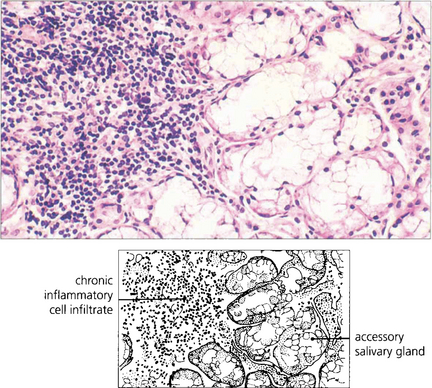

SJÖGREN’S SYNDROME

Fig. 5.35 This patient illustrates the typical changes of dry eyes and mouth associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Patients also have a small but statistically significant risk of developing a lymphoma. Mild cases respond to treatment with wetting agents. Occlusion of the lacrimal puncta by plugs or cautery alleviates symptoms in the more severe cases.

SUPERIOR LIMBIC KERATOCONJUNCTIVITIS

Fig. 5.37 This patient, who had previously been treated for thyrotoxicosis, presented with a history of sore eyes for many months. There is some lid oedema and lid retraction.

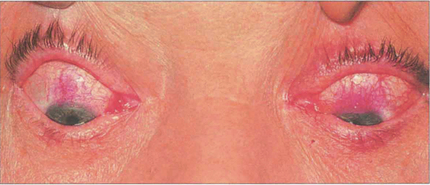

Fig. 5.38 Rose bengal drops have been instilled into both eyes, which demonstrate the characteristic upper limbal staining from the 10 o’clock to the 2 o’clock positions in each eye. Typically, there is bilateral involvement which is best seen in the position of downgaze. The changes are more marked in the left eye, where a diffuse limbal infiltration extends on to the cornea and upwards on to the bulbar conjunctiva.

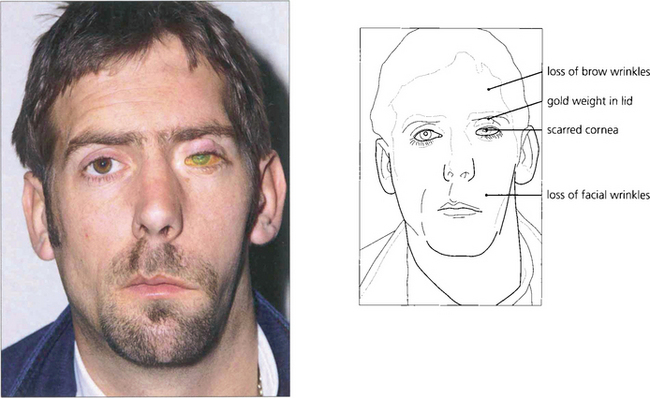

NEUROTROPHIC KERATITIS

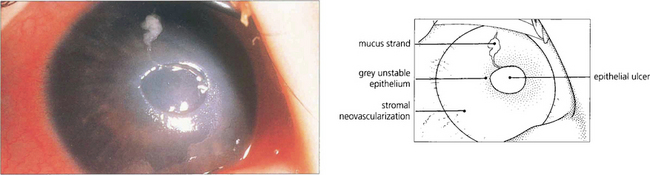

Fig. 5.40 Neurotrophic keratitis results from partial or complete corneal denervation. Soon after denervation the surface epithelial cells of the cornea and conjunctiva lose their microvillae which hold the mucin layer of the tear film. The tear film becomes unstable because of the nonwetting surface and the eye is very vulnerable to infection and minor trauma. In this example there is a shallow ulcer due to loss of epithelium and the surrounding epithelium is grey and unstable. Botulin toxin-induced ptosis, a gold weight in the upper lid or a permanent tarsorrhaphy may prove necessary for corneal protection.

SOLAR AND CLIMATIC EXPOSURE

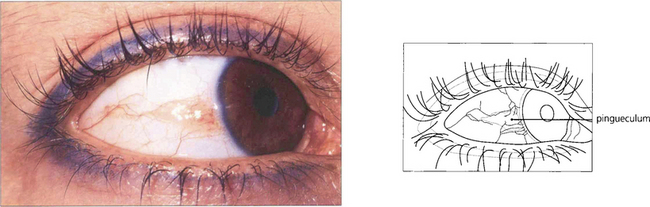

Excessive exposure to outdoor conditions, and especially ultraviolet radiation, is associated with degenerative conjunctival changes that produce an irritable eye from tear film disturbance and localized inflammation. Translucent deposits can be seen in the corneal stroma. (See also Fig. 6.44.)

Fig. 5.42 Pingueculae are raised yellowish patches that enlarge gradually until they abut the cornea but do not encroach upon it. Histologically they are formed by elastotic degeneration of collagen within the substantia propria.

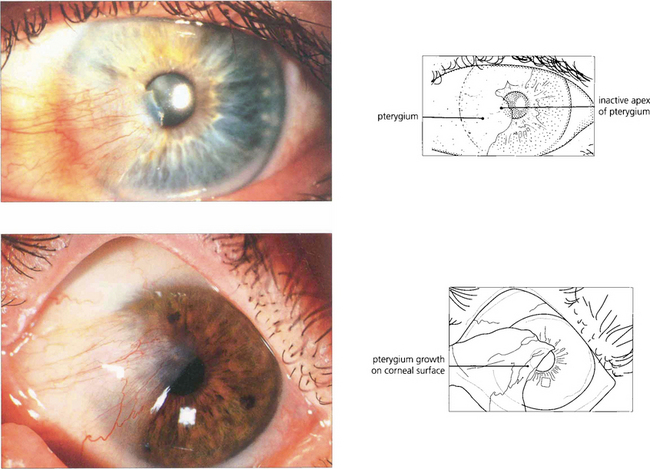

Fig. 5.43 A pterygium is a raised triangular area of bulbar conjunctiva that grows over the superficial cornea and produces visual symptoms either from direct encroachment on the pupil or from irregular astigmatism. Pterygia normally occur on the nasal bulbar conjunctiva. This is thought to be caused by the cornea focusing on lateral light from the temporal side on the nasal limbus damaging the nasal limbal stem cells. In temperate climates pterygia progress only very slowly and rarely cause visual symptoms but in sunny, hot, dusty regions of the world they can represent a serious threat to vision. Examination of the leading edge and body of the lesion shows whether the pterygium is active by the degree of vascular engorgement in the bulk of the lesion. These pterygia are quiescent: the eye is white, they are not inflamed and the vessels in the lesion are not engorged. Surgical removal is indicated if visual impairment is threatened or if the lesion causes discomfort but the recurrence rate is high, particularly if solar exposure continues. Postoperative recurrence can be reduced by using a conjunctival graft.

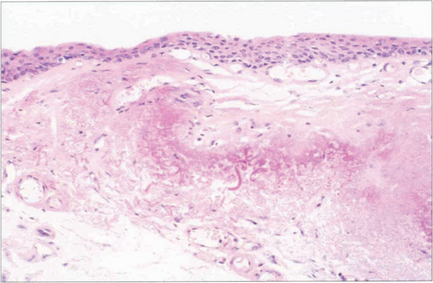

Fig. 5.44 Histological examination shows that the pterygium consists of hyalinized subepithelial collagen with elastotic degeneration. At the apex of the pterygium on the cornea there is fragmentation and destruction of Bowman’s layer. Similar, but less vascular, changes are seen in a pinguecula (which probably represents the initial stage of the disease).

NUTRITIONAL XEROPHTHALMIA

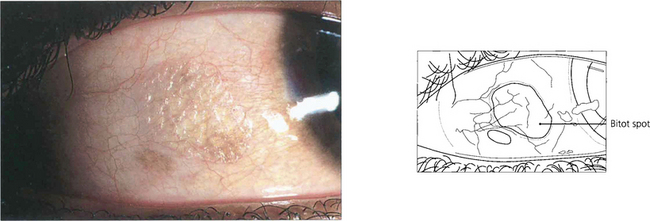

Fig. 5.45 In the vitamin A-deficient eye there is a drying and wrinkling of the conjunctiva associated with the development of Bitot’s spots. These spots are small, white, cheese-like patches which may have a foamy appearance and do not wet easily. At this stage a punctate keratopathy may also appear.

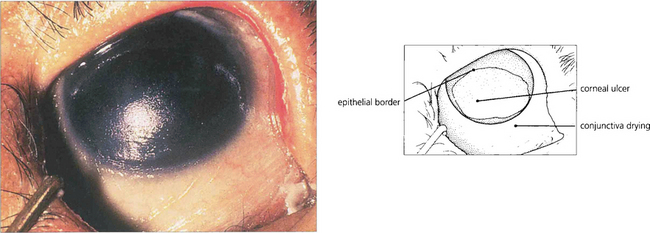

Fig. 5.46 This photograph shows a late stage in the development of vitamin A deficiency in which the corneal epithelium is lost over the lower nasal part of the exposed eye. Note the dry, wrinkled conjunctiva.

DISEASES OF THE SCLERA AND EPISCLERA

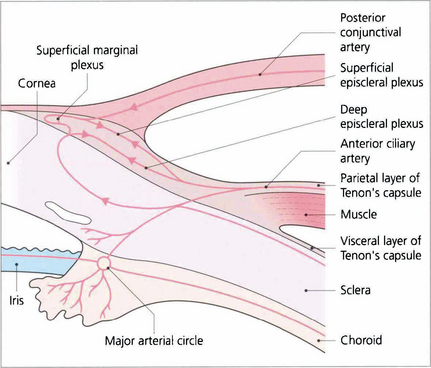

Fig. 5.49 The vascular supply of the anterior episclera and sclera are best examined at the slit lamp. The importance of understanding the vascular anatomy lies in the clues that it provides in differentiating the clinical patterns of inflammation with episcleritis and scleritis. Three layers of vessels are visible. The conjunctival plexus is the most superficial layer and can be distinguished clinically by its ability to be moved over the underlying structures. The superficial episcleral plexus is a radially arranged series of vessels within Tenon’s capsule that anastomose at the limbus with the conjunctival vessels and the underlying deep episcleral plexus that is closely applied to the sclera. The vessels in this layer are arranged in an irregular, reticular, nonradial fashion and, unlike the conjunctival and superficial layers, are not blanched by a drop of 1:1000 epinephrine.

EPISCLERITIS

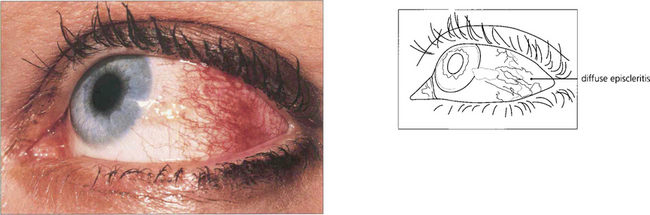

Fig. 5.50 Diffuse episcleritis may affect a sector or the whole anterior segment of the globe. In this example the radial superficial episcleral vessels are dilated and, although there is some associated engorgement of the conjunctival and deep episcleral plexus, there is no scleral swelling or oedema.

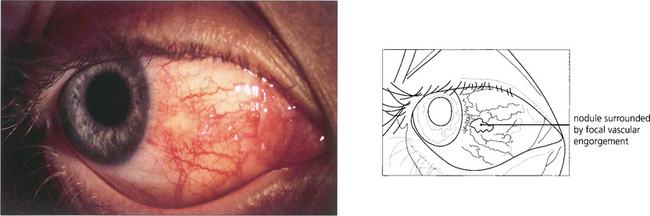

Fig. 5.51 In nodular episcleritis the oedema and infiltration of the episclera are localized to one or more sites with engorgement of episcleral vessels around a central pale nodule. The nodules are mobile over the underlying sclera, they are not really tender and there is no scleral oedema. Resolution of nodular episcleritis tends to occur more slowly than in diffuse episcleritis and topical steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may help.

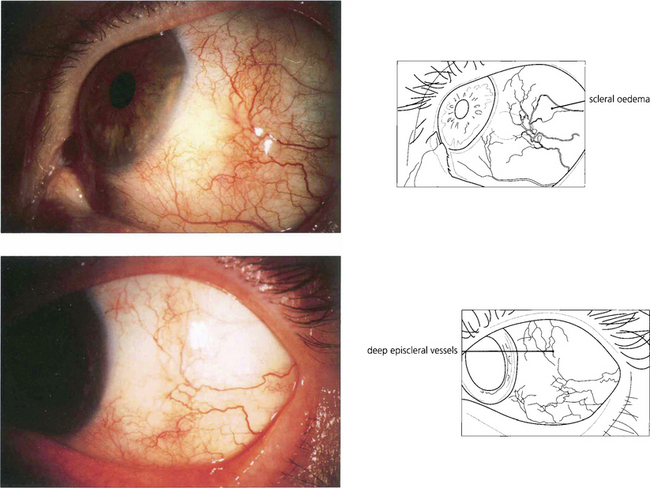

Fig. 5.52 The conjunctival vessels and superficial episcleral vessels can be blanched by a drop of 10% phenylnephrine or 1:1000 epinephrine, which is useful in differentiating scleritis from episcleritis as the deep episcleral plexus and the scleral oedema are seen more easily. The superficial episcleral plexus has a radial distribution; this is helpful in distinguishing the vascular changes of episcleritis from the more net-like deep episcleral plexus.

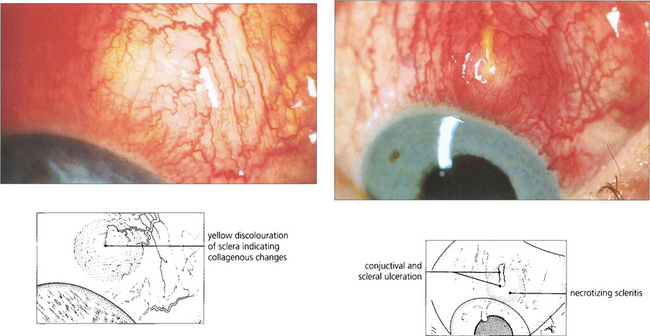

SCLERITIS

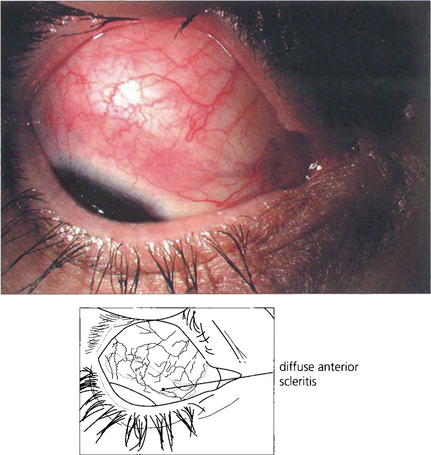

Fig. 5.53 Diffuse anterior scleritis is the commonest and least severe form of scleritis accounting for up to 50 per cent of cases. It can be widespread or confined to one quadrant.

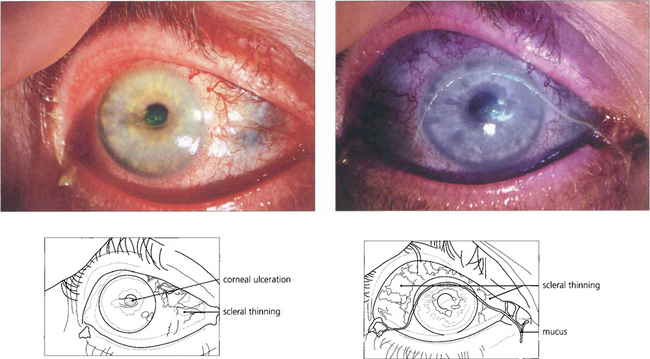

Fig. 5.54 A small number of patients may progress to necrotizing changes with repeated attacks. This patient with rheumatoid arthritis shows active scleritis with scleral thinning. The eye is dry with mucus in the tear film and a small area of central corneal ulceration stained with fluorescein.

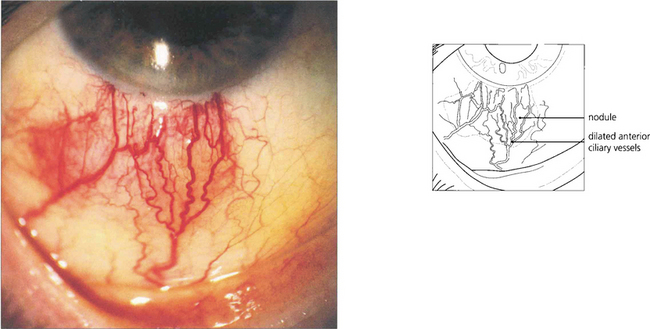

Fig. 5.55 Nodular anterior scleritis is the second most common type of scleritis. It may appear to be similar to nodular episcleritis on superficial examination but the nodules are tender, associated with scleral swelling and cannot be moved over the tissues. Initial attacks resolve without scleral destruction but about 20% of patients progress to necrotizing disease with repeated attacks.

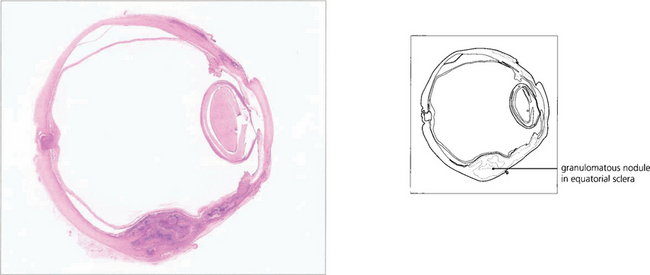

Fig. 5.56 Histological examination of an enucleated eye showing a granulomatous nodule in the equatorial sclera.

Fig. 5.57 Necrotizing anterior scleritis is the most serious form of scleritis and is usually very painful. The first indication of necrotizing change is vaso-occlusion or venular shutdown in areas of scleral inflammation. These areas are pale, even though the eye still appears congested. Vascular closure is followed by scleral thinning and bluish changes or scleral infarction when the affected area becomes white and sloughs. Unless the scleritis is adequately and promptly treated the condition will progress with increasing tissue destruction and potential loss of the eye. The management of these patients is difficult as they are often ill from systemic disease and the side-effects of treatment. High-dose oral or intravenous steroids are needed and cyclosporin, methotrexate or cyclophosphamide can be effective in recalcitrant cases. This patient shows an area of vascular closure that progressed to necrosis and ulceration 10 days later.

Fig. 5.58 Necrotizing anterior scleritis without inflammation, also known as scleromalacia perforans, is characterized by painless progressive thinning of the sclera in the absence of symptoms and with minimal inflammatory signs as a result of arteriolar occlusion of the deep episcleral vascular network. Pathologically there is infarction and sequestration of the affected area. It is nearly always associated with severe long-standing seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. In this example, the scleritis has resulted in conjunctival ulceration and guttering of the adjacent cornea, possibly as a dellen.

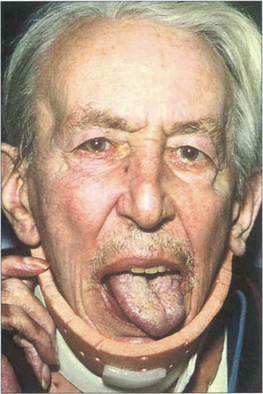

Fig. 5.59 Patients with scleromalacia perforans usually have severe long-standing rheumatoid arthrits. This patient (the same one as in Fig. 5.58) has a left 12 th nerve palsy from cervical arthritis.

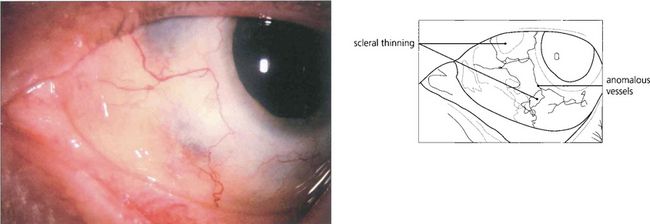

Fig. 5.60 After resolution of an anterior diffuse necrotizing scleritis in a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis, the eye shows scleral thinning. On slit-lamp examination, rearrangement of the remaining collagen bundles can be seen with changes in the vascular pattern over the lesion and at the limbus.

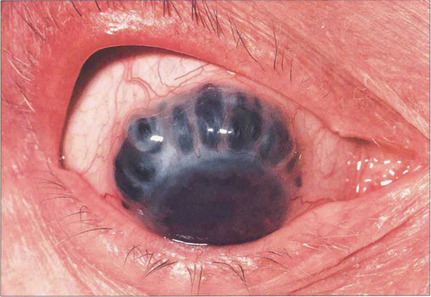

Fig. 5.61 Scleral thinning allows the dark choroidal pigmentation to be seen. Staphylomas usually result from raised intraocular pressure in the presence of scleral thinning. Perforation of the globe is rare in the absence of trauma.

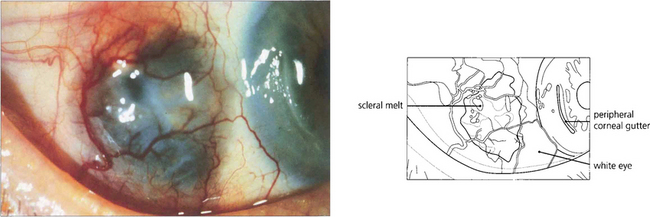

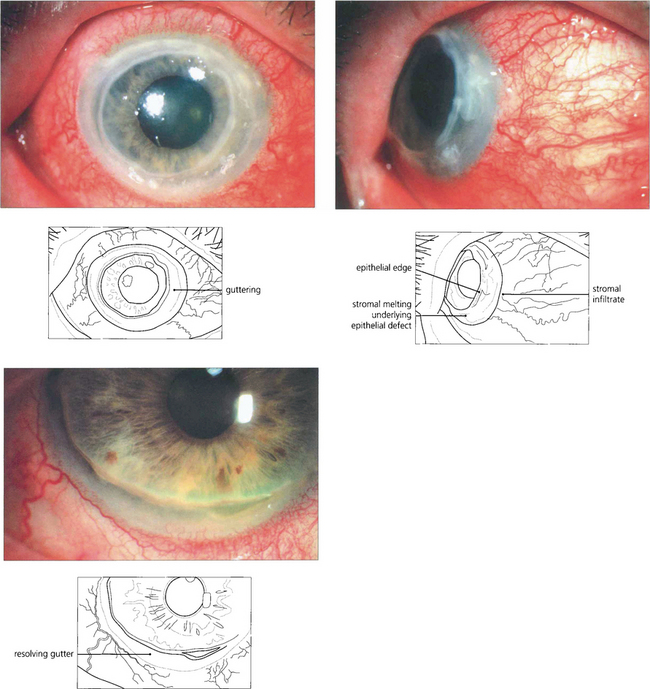

Fig. 5.62 In this patient keratitis involves the whole circumference of the peripheral cornea (top left). Corneal stromal melting can be seen on lateral gaze (top right). With resolution of inflammation following systemic immunosuppression, an epithelialized peripheral corneal gutter persists (left).

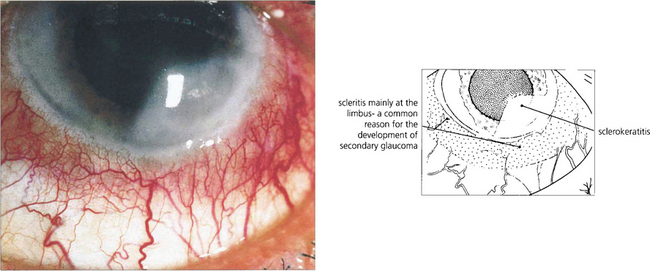

Fig. 5.63 Sclerokeratitis may complicate an anterior scleritis when a diffuse peripheral opacity can be seen in the adjoining corneal stroma. In active disease, the whole thickness of the corneal stroma adjacent to a patch of scleritis may melt and ulcerate. Impending perforation may require a tectonic peripheral corneal transplant. This type of active limbitis is often accompanied by an acute rise in intraocular pressure and KP on the adjacent corneal endothelium.

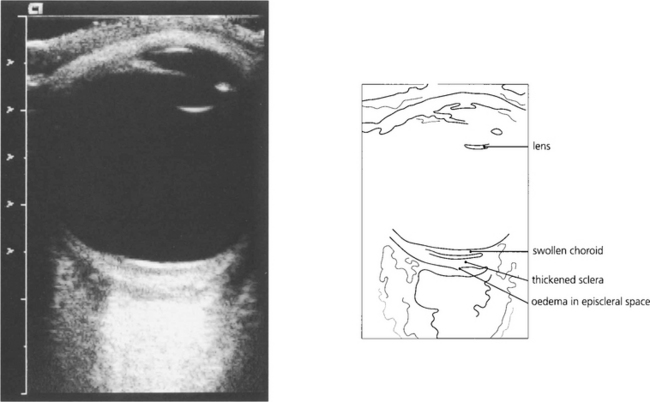

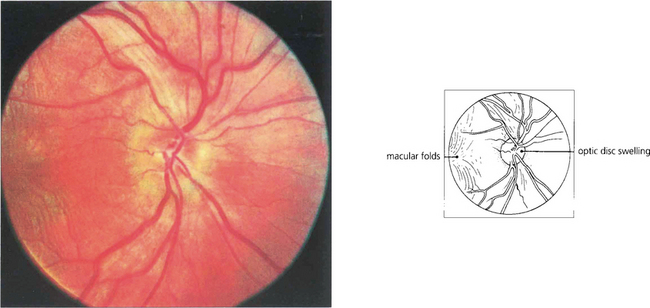

Fig. 5.64 The diagnosis of posterior scleritis is frequently overlooked. The patient presents with ocular pain and visual loss from exudative retinal detachment, macular oedema or disc swelling. Although some patients have anterior involvement, inflammatory signs may be minimal and apparent only if the posterior sclera is examined by getting the patient to look in extreme gaze. With severe inflammation, there may also be proptosis and extraocular muscle involvement and the differentiation from orbital myositis or pseudo-tumour becomes difficult and perhaps academic. Fundus examination of a relatively mild case here shows slight optic disc swelling and subretinal fluid producing macular folds.