Alimentary Tract Duplications

Alimentary tract duplications have been described for hundreds of years and multiple terms have been used in the literature. The current term duplication of the alimentary tract and a common description of the congenital malformation was applied by William Ladd in 1937.1 Three common findings were described: a well-developed smooth muscle coat, an epithelial lining, and attachment to the alimentary tract. The first large series to appear in the literature by Gross et al. in 1952 supported these findings as well.2

Embryology

The incidence of duplications has been reported to be 1 in 4500 births.3 Two types are encountered: cystic and tubular, with cystic being the most common. Duplications are considered congenital malformations thought to arise from disturbances in embryologic development. Multiple theories have been postulated to account for their development. A persistent embryonic diverticulum from the alimentary tract was the first theory reported in the literature4, while a defect in the recanalization of the lumen of the alimentary tract was proposed years later.5 The coincidental finding of colonic and genitourinary duplications and similar findings in conjoined twins led to the partial twinning theory.6,7 The ‘split notochord’ theory was proposed because of the association of enteric duplications and spinal anomalies8, and relatively recent literature supports the notochord as being important in the development of both foregut and hindgut duplications.9,10 Fetal hypoxia has also been implicated in the development of duplications.11,12

The associated findings of vertebral, spinal cord, and genitourinary malformations as well as malrotation and intestinal atresia suggest a multifactorial process in the development of alimentary tract duplications.2,13,14 No single theory has been described to account for these heterogeneous malformations.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

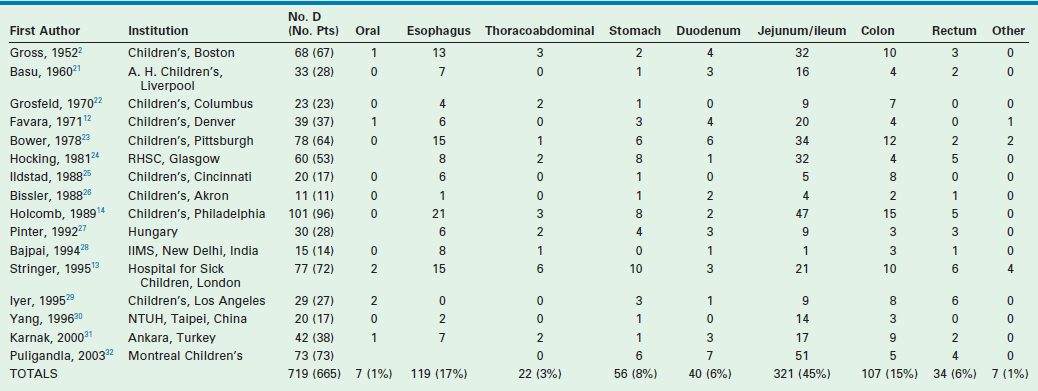

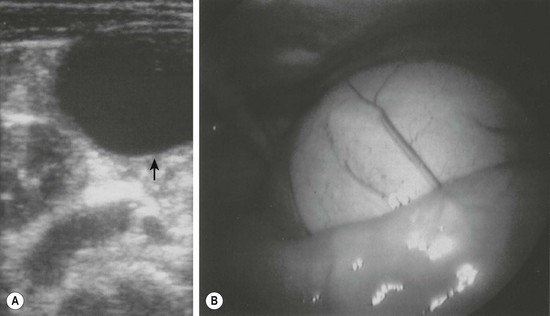

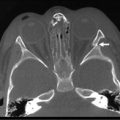

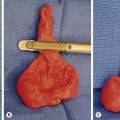

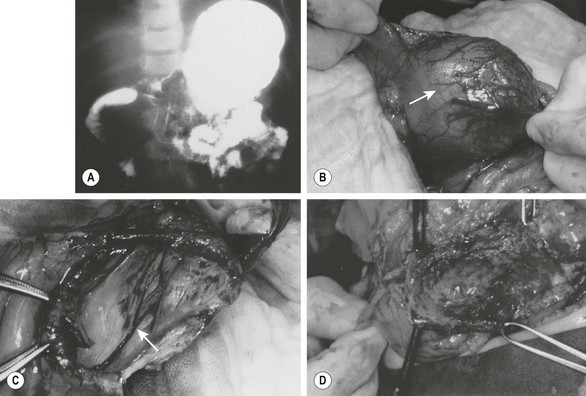

Alimentary tract duplications present with a wide range of symptoms including abdominal distension and/or pain, obstruction, bleeding, respiratory compromise, or a painless mass. Generally, the symptoms are related to size, location, type of duplication, and presence of heterotopic mucosa. Most (80%) present before 2 years of age; prenatal ultrasound is detecting duplications as early as 16 weeks gestational age.13–15 The majority of duplications are cystic and the remaining are tubular (Fig. 39-1). The jejunum/ileum is the most common location followed by the esophagus (Table 39-1). The epithelial lining is usually native to the surrounding lesion but heterotopic mucosa is found in 25–30% of duplications.14 Gastric tissue is the most common type of ectopic mucosa encountered followed by both exocrine and endocrine pancreatic tissue. Ectopic gastric mucosa may lead to peptic ulceration with subsequent hemorrhage or perforation (Fig. 39-2).

FIGURE 39-1 (A) Most alimentary tract duplications are cystic. (B) A tubular duplication is seen. Note that the native bowel is bifurcated (arrow) into the tubular duplication and native intestine.

FIGURE 39-2 Most intestinal bleeding from duplications is caused by tubular duplications with communication to the intestine. However, in this case, the bleeding was due to mucosal ulceration (solid arrow) secondary to an adjacent cystic duplication. (From Holcomb GW III, Gheissari A, O’Neill JA, et al. Surgical management of alimentary tract duplications. Ann Surg 1989;209:167–74.)

Multiple imaging modalities are utilized to make the diagnosis. Plain radiographs may reveal a mediastinal mass, suggesting an esophageal duplication. Contrast studies may show a mass effect or communication with the alimentary tract. ultrasound is radiation free and noninvasive, making it a useful test, particularly for intra-abdominal duplications.16 A typical sonographic appearance of duplications demonstrates an inner hyperechoic rim of muscosa–submucosa and an outer hypoechoic muscular layer (Fig. 39-3).17 A history of anemia or bleeding with a suspected duplication suggests ectopic gastric mucosa, and technetium-99m (99mTc) scintigraphy is a useful imaging modality.18,19 In cases where a combined thoracoabdominal duplication is suspected, computed tomography (CT) may aid in diagnosis. The presence of vertebral abnormalities and esophageal duplications is best investigated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).20

Classification and Treatment by Location

To better understand the wide presentation and surgical treatment of duplications, they will be discussed according to anatomic location. A compilation of major case series reported in the last 60 years from 16 different institutions is seen in Table 39-1.2,13–14,21–32 The report with the largest number of patients described 101 duplications in 96 patients.14

Esophageal Duplications

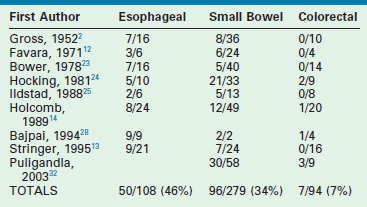

Approximately 20% of duplications arise from the esophagus. While cervical duplications do occur, the majority are located on the right side of the thoracic esophagus. Most are cystic and do not share a common muscular wall or communicate with the esophageal lumen. Clinical presentation will depend upon mass effect. Duplications impinging upon the trachea may lead to respiratory distress or pneumonia. In older patients, dysphagia may develop. Duplications should be in the differential diagnosis for any patient presenting with a mediastinal mass. Almost half of all esophageal duplications contain ectopic gastric mucosa so peptic ulceration leading to anemia or hematemesis can be seen (Table 39-2). Communication with the spinal canal is seen in 20% of patients.14 Once a duplication is suspected on chest radiography or esophagography, further imaging with either CT or MRI should be performed (Fig. 39-4). It is important to evaluate for synchronous abdominal duplications as a 25% incidence has been described.14 With the increased use of thoracoscopy, many esophageal duplications are being resected with a minimally invasive approach rather than the traditional thoracotomy.33,34

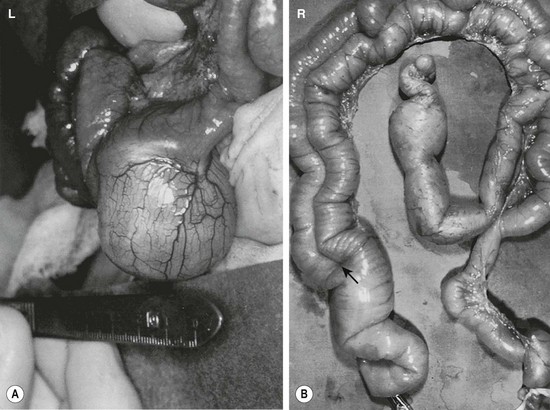

Thoracoabdominal Duplications

Extension of an esophageal duplication into the abdomen is known as a thoracoabdominal duplication. These are quite rare accounting for approximately 3% of all duplications. The length of extension can vary from the stomach to the jejunum, with jejunal connections being the most common.13,14 These duplications are all tubular and ectopic gastric mucosa is found in a high percentage. Clinical presentation can range from asymptomatic to hemorrhage or ulceration from ectopic gastric mucosa. A higher incidence of vertebral anomalies (88%) in these patients warrants either CT or MRI to exclude neuroenteric communication (Fig. 39-5).13,14 The current treatment is a one-stage combined thoracoabdominal approach for resection.

FIGURE 39-5 A 3-year-old was found to have a right paravertebral mass. (A) A large anterior defect in the vertebral bodies of the upper thoracic spine (arrow) is seen. (B) This myelogram shows the filling defect caused by a neuroenteric cyst. (C) The contrast agent from the myelogram is seen in the neuroenteric cyst (upper arrow) with extension subdiaphragmatically (lower arrow) into the distal small intestine. (From Holcomb GW III, Gheissari A, O’Neill JA, et al. Surgical management of alimentary tract duplications. Ann Surg 1989;209:167–74.)

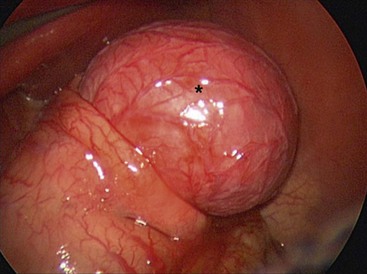

Gastric Duplications

Gastric duplications account for 8% of alimentary tract duplications and usually become symptomatic early in life, frequently presenting with pain, emesis, or melena. Unlike other duplications, a female predilection is seen.6 Most are cystic and arise from the greater curvature and no intraluminal connection is seen (Figs 39-6 and 39-7). Peptic ulceration with hemorrhage or perforation may occur if an intraluminal connection is present. Abdominal ultrasound can usually diagnose the duplication, but pancreatic pseudocysts or choledochal cysts may have the same appearance. A contrast upper gastrointestinal series or CT can help clarify the anatomy.

FIGURE 39-6 (A) This patient had nonbilious emesis and was found to have a mass effect on the antrum with extrinsic compression of the second portion of the duodenum on this contrast study. (B) A gastric duplication (arrow) was found emanating from the inferior aspect of the greater curvature of the gastric antrum at operation. It was thought best to marsupialize the duplication, because a significant partial gastrectomy would be required to remove this lesion completely. (C) The duplication has been marsupialized, and the mucosa (arrow) of the duplication lying on the common wall with the stomach is seen. (D) The mucosa has been stripped, leaving intact the common wall between the duplication and the gastric antrum. (From Holcomb GW III, Gheissari A, O’Neill JA, et al. Surgical management of alimentary tract duplications. Ann Surg 1989;209:167–74.)

FIGURE 39-7 A neonate was found to have pyloric atresia and underwent laparoscopic correction. At laparoscopy, a large gastric duplication (asterisk) was seen emanating from the greater curvature of the stomach. The duplication was excised and the greater curvature closed. The patient recovered uneventfully and did not develop any postoperative problems.

Duodenal and Pancreatic Duplications

Duodenal duplications account for 6% of all duplications and may be asymptomatic, or may present with intestinal obstruction secondary to cyst secretions or hemorrhage related to ectopic gastric mucosa which is found in 13% of specimens.35 Most are cystic and noncommunicating with the lumen, but occasionally tubular variants are seen.36 The anatomic locations of these duplications may obstruct the biliopancreatic ducts and cause jaundice or pancreatitis. Abdominal ultrasound or CT scan are commonly used for diagnosis.

The anatomic location and tenuous blood supply of these duplications dictate the operative approach. Simple excision is preferred, but the intimate relationship to the biliary or pancreatic ducts may warrant Roux-en-Y cystjejunosotomy.37 Recently, the use of endoscopy for the treatment of duodenal duplications has been described in the literature.38

Pancreatic duplications are the rarest type of alimentary tract duplication. Commonly presenting with abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, or a palpable mass, they can easily be mistaken for a pancreatic pseudocyst. The pancreatic head is involved in half of cases (51%). Intraoperative frozen section evaluation will differentiate a duplication from a pseudocyst. Simple cyst resection is preferred but the location may dictate a more complex resection.39

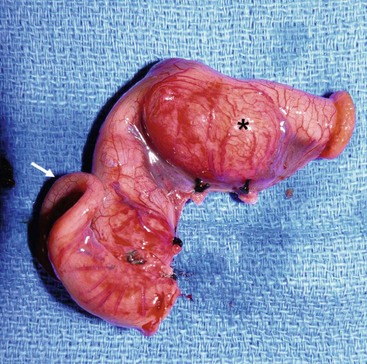

Small Bowel Duplications

Small bowel duplications account for almost half (45%) of all reported duplications. They may be cystic or tubular (Fig. 39-8). Tubular duplications vary in size from a few centimeters to the entire length of bowel. Small bowel duplications may share a common wall or be entirely separate from the native intestine. They arise from the mesenteric side and share a common blood supply. The most common location is the ileum (34%).13,14,23

FIGURE 39-8 This small bowel duplication (asterisk) was located in the terminal ileum and required removal of the terminal ileum as well as the cecum. Note the appendix (arrow) attached to the cecum. A primary anastomosis was performed.

Small bowel duplications are frequently seen in childhood secondary to a palpable mass, obstruction, or hemorrhage. The duplication may lead to volvulus, which is sometimes seen in neonates. In older children intussusception is more common with the duplication acting as the lead point.14 Abdominal ultrasound is usually the initial imaging study to evaluate these duplications. Additional studies such as CT or small bowel contrast study are usually less helpful and lead to unnecessary radiation exposure. The presence of ectopic gastric mucosa is found in 80% of tubular and 20% of cystic duplications.32 Also these duplications can be mistaken for a Meckel diverticulum on technetium scanning. Laparoscopy is increasingly being used for both diagnosis and treatment of duplications, thereby eliminating open exploration and decreasing hospital stay.32,40

Operative treatment of small bowel duplications will vary based on the type and size. Small cystic duplications can be enucleated provided the native blood supply can be left intact. Small bowel resection with primary anastomosis is the usual approach. Long tubular duplications may pose a challenge because of the intimate blood supply to the native bowel. Resections of large lengths of bowel increase complications and may lead to short bowel syndrome. In this situation, mucosal stripping through multiple enterotomies will preserve bowel length and decrease the risk of ulceration or hemorrhage from ectopic gastric mucosa.41

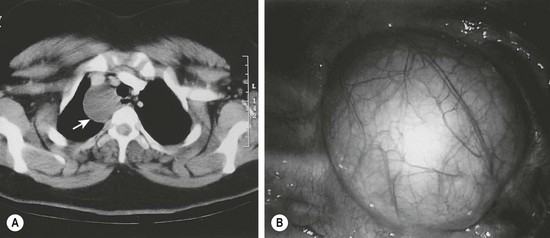

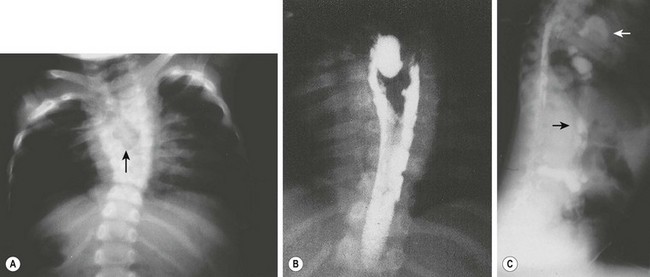

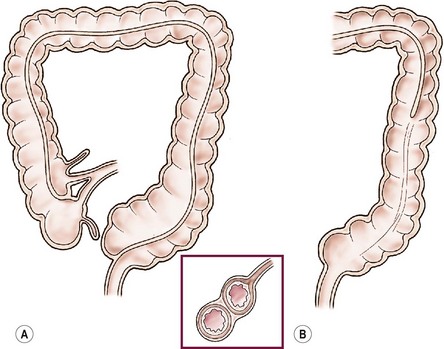

Colonic Duplications

Colonic duplications account for approximately 15% of all duplications. Typically found on the mesenteric side of the bowel, most occur in the cecum and are cystic. However tubular duplications are seen, and vary in length and complexity (Fig. 39-9). Large bowel obstruction secondary to compression, intussusceptions, and volvulus are the usual presenting symptoms. Since colonic duplications rarely contain ectopic gastric mucosa, gastrointestinal bleeding is infrequent. However a higher number of associated anomalies are present with long tubular duplications. With total colonic tubular duplications, other duplicate structures such as bladder, vagina, and external genitalia are described, supporting the partial twinning theory of embryogenesis.42,43 To better categorize tubular duplications, a classification system has been described.44 Type I colonic duplications are limited to the colon, whereas type II have associated genital or urinary tract duplications.

FIGURE 39-9 Ileal and colonic tubular duplications vary in length and complexity. (A) The terminal ileum is seen to bifurcate into native colon and duplicated colon, which is medial to the native colon. In this scenario the duplicated colon ends blindly in the upper rectum. (B) In this drawing, the duplicated colon communicates with the native colon and forms a common descending colon.

The treatment of colonic duplications will vary depending on the type and size. As with small cystic duplications, enucleation is possible but resection and anastomosis is usually needed. Long tubular duplications present a difficult challenge. If resection is deemed too aggressive, a distal communication with native bowel can be created to relieve the obstruction (Fig. 39-10). Since colonic duplications rarely contain ectopic gastric mucosa, mucosal stripping is rarely needed. Long tubular duplications with distal communication are often treated conservatively with stool softeners. If a fistulous tract to the bladder or uterus is present, it should be excised.

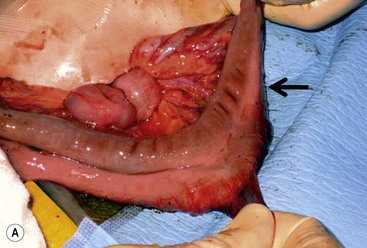

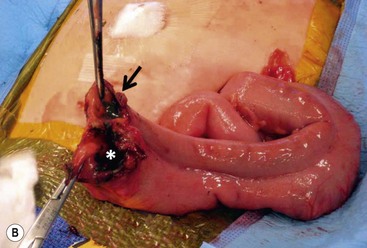

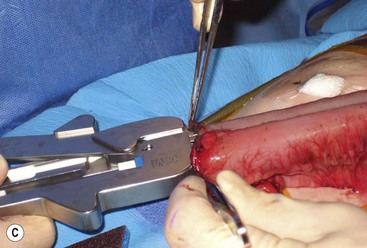

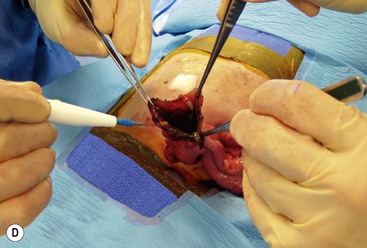

FIGURE 39-10 This female infant was born with high imperforate anus and a duplicate vagina, and underwent initial colostomy. At the time of the colostomy, it was noted that she had a tubular colonic duplication. (A) Note where the tubular colonic duplication starts in the transverse colon (arrow). (B) After takedown of the colostomy, the two lumens of the colonic duplication are seen (asterisk and arrow). (C) A stapler is utilized to create a common channel between the two lumens. Note the dressing on the umbilicus as laparoscopy was used to completely mobilize the colon. (D) This end-on view shows a single lumen created after using the stapler to create the common lumen. This lumen was then anastamosed to the rectum.

Rectal Duplications

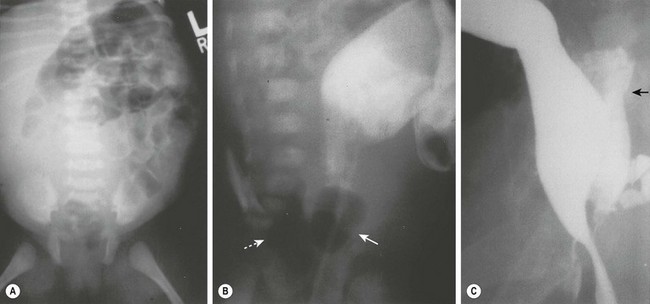

Rectal duplications account for approximately 6% of duplications, and are commonly found in the presacral space posterior to the rectum (Fig. 39-11). Chronic constipation is commonly found secondary to the posterior mass effect. Digital rectal examination may reveal a mass, leading to contrast enema for diagnosis. A perineal fistula should raise the suspicion for a perirectal abscess. Treatment of rectal duplications can vary from a transanal approach for marsupialization, or division of the septum between the duplication and the native rectum. A posterior sagittal approach is an alternative for more extensive duplications. Some patients may require an initial colostomy for large or complicated duplications.

FIGURE 39-11 (A) Radiograph of a neonate with abdominal distention and evidence of a pelvic mass. On rectal examination, a mass was palpable posterior to the rectum. (B) A contrast study in which an 8-Fr Foley catheter was introduced into the rectum, and the balloon was inflated with air (solid arrow). Posterior to the rectum and compressing it is a rectal duplication with air (dotted arrow), indicating communication to the gastrointestinal tract. A colostomy was initially performed because of the rectal obstruction. (C) A barium enema was performed at age 6 months in this patient. On this lateral radiograph, filling of the posterior rectal mass is seen (arrow). (From Holcomb GW III, Gheissari A, O’Neill JA, et al. Surgical management of alimentary tract duplications. Ann Surg 1989;209:167–74.)

References

1. Ladd, WE. Duplications of the alimentary tract. South Med J. 1937; 30:363–371.

2. Gross, RE, Holcomb, GW, Farber, S. Duplications of the alimentary tract. Pediatrics. 1952; 9:449–467.

3. Schalamon, J, Schleef, J, Hollworth, ME. Experience with gastrointestinal duplications in childhood. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2000; 385:402–405.

4. Lewis, FT, Thyng, FW. Regular occurrence of intestinal diverticula in embryos of pig, rabbit, and man. Am J Anat. 1908; 7:505–519.

5. Bremer, JL. Diverticula and duplications of the intestinal tract. Arch Pathol. 1944; 38:132–140.

6. Smith, ED. Duplication of the anus and genitourinary tract. Surgery. 1969; 66:909–921.

7. Lewis, PL, Holder, T, Feldman, M. Duplication of the stomach: Report of a case and review of the English literature. Arch Surg. 1961; 82:634–640.

8. Bentley, JFR, Smith, JR. Developmental posterior enteric remnants and spinal malformations: The split notochord syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1960; 35:76–86.

9. Qi, BQ, Beasley, SW, Williams, AK. Evidence of a common pathogenesis for foregut duplications and esophageal atresia with tracheo-esophageal fistula. Anat Rec. 2001; 264:93–100.

10. Qi, BQ, Beasley, SW, Frizelle, FA. Evidence that the notochord may be pivotal in the development of sacral and anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:1310–1316.

11. Mellish, RWP, Koop, CE. Clinical manifestations of duplication of the bowel. Pediatrics. 1961; 27:397–407.

12. Favara, BE, Franciosi, RA, Akers, DR. Enteric duplications: Thirty-seven cases: A vascular theory of pathogenesis. Am J Dis Child. 1971; 35:501–506.

13. Stringer, MD, Spitz, L, Abel, R, et al. Management of alimentary tract duplication in children. Br J Surg. 1995; 82:74–78.

14. Holcomb, GW, III., Gheissari, A, O’Neill, JA, et al. Surgical management of alimentary tract duplications. Ann Surg. 1989; 209:167–174.

15. Laje, P, Flake, AW, Adzick, NS. Prenatal diagnosis and postnatal resection of intraabdominal enteric duplications. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:1554–1558.

16. Hur, J, Yoon, CS, Kim, MJ, et al. Imaging features of gastrointestinal tract duplications in infants and children: From oesophagus to rectum. Pediatr Radiol. 2007; 37:691–699.

17. Barr, LL, Hayden, CK, Jr., Stansberry, SD, et al. Enteric duplication cysts in children: Are their ultrasonographic wall characteristics diagnostic? Pediatr Radiol. 1990; 20:326–328.

18. Lecouffe, P, Spyckerelle, C, Venel, H, et al. Use of pertechnetate 99mTc abdominal scanning in localizing an ileal duplication cyst: Case report and review of the literature. Eur J Nucl Med. 1992; 19:65–67.

19. Kumar, R, Tripathi, M, Chandrashekar, N, et al. Diagnosis of ectopic gastric mucosa using 99mTc pertechnetate: A spectrum of scintigraphic findings. Br J Radiol. 2005; 78:714–720.

20. Haddon, MJ, Bowen, A. Bronchopulmonary and neuroenteric forms of foregut anomalies: Imaging for diagnosis and management. Radiol Clin North Am. 1991; 29:241–254.

21. Basu, R, Forshall, I, Rickham, PP. Duplications of the alimentary tract. Br J Surg. 1960; 47:477–484.

22. Grosfeld, JL, O’Neill, JA, Clatworthy, HW. Enteric duplications in infancy and childhood: An 18-year review. Ann Surg. 1970; 172:83–90.

23. Bower, RJ, Sieber, WK, Kiesewetter, WB. Alimentary tract duplications in children. Ann Surg. 1978; 188:669–674.

24. Hocking, M, Young, DG. Duplications of the alimentary tract. Br J Surg. 1981; 68:92–96.

25. Ildstad, ST, Tollerud, DJ, Weiss, RG, et al. Duplications of the alimentary tract. Ann Surg. 1988; 208:184–189.

26. Bissler, JJ, Klein, RL. Alimentary tract duplications in children: Case and literature review. Clin Pediatr. 1988; 27:152–157.

27. Pinter, AB, Schubert, W, Szemledy, F, et al. Alimentary tract duplications in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1992; 2:8–12.

28. Bajpai, M, Mathur, M. Duplication of the alimentary tract: Clues to the missing links. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:1361–1365.

29. Iyer, CP, Mahour, GH. Duplications of the alimentary tract in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995; 30:1267–1270.

30. Yang, MC, Duh, YC, Lai, HC, et al. Alimentary tract duplications. J Formos Med Assoc. 1996; 95:406–409.

31. Karnak, I, Ocal, T, Senocak, ME, et al. Alimentary tract duplications in children: Report of 26 years’ experience. Turk J Pediatr. 2000; 42:118–125.

32. Puligandla, PS, Nguyen, LT, St-Vil, D, et al. Gastrointestinal duplications. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:740–744.

33. Bratu, I, Laberge, JL, Flageole, H, et al. Foregut duplications: Is there an advantage to thoracoscopic resection? J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:138–141.

34. Merry, C, Spurbeck, W, Lobe, TE. Resection of foregut-derived duplications by minimal-access surgery. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999; 15:224–226.

35. Vertruyen, M, Cadiere, GB, Jacobvitz, D, et al. A propos de 2 cas de duplication duodenale. Acta Chir Belg. 1991; 91:140–144.

36. Merrot, T, Anastasescu, R, Pankevych, T, et al. Duodenal duplications: Clinical characteristics, embryological hypotheses, histological findings, treatment. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 16:18–23.

37. Leenders, EL, Odsman, MZ, Sukarochana, K. Treatment of duodenal duplication with international review. Am Surg. 1970; 36:368–371.

38. Romeo, E, Torroni, F, Foschia, F, et al. Surgery or endoscopy to treat duodenal duplications in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 40:874–878.

39. Hunter, CJ, Connelly, ME, Ghaffari, N, et al. Enteric duplication cysts of the pancreas: A report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008; 24:227–233.

40. Schalamon, J, Schleef, J, Höllwarth, ME. Experience with gastrointestinal duplications in childhood. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000; 385:402–405.

41. Wrenn, EL, Jr. Tubular duplication of the small intestine. Surgery. 1962; 52:494–498.

42. Smith, ED, Stephens, FD. Duplication and vesicointestinal fissure. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1988; 24:551–580.

43. Ravitch, MM. Hind gut duplication-doubling of colon and genital urinary tracts. Ann Surg. 1953; 137:588–601.

44. Kottra, JJ, Dodds, WJ. Duplication of the large bowel. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1971; 113:310–315.