Chapter 40 ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

PATHOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Symptoms and signs are not reliable indicators of the presence or severity of ALD. There may be no symptoms even in the presence of cirrhosis. In other cases, clinical features do allow a confident diagnosis. The clinical and pathological spectrum of alcoholic liver disease includes fatty liver, hepatitis and cirrhosis, but these commonly coexist.

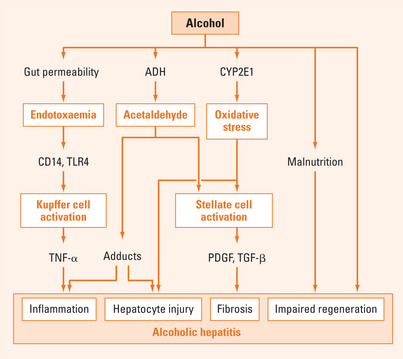

Alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis is defined pathologically by polymorphonuclear infiltration with hepatocyte injury (ballooning necrosis and apoptosis), accumulation of Mallory’s hyaline (derived from intermediate filaments) and variable hepatic fibrosis. It presents with anorexia, nausea and abdominal pain, with jaundice, bruising and encephalopathy in association with alcohol abuse. Hepatomegaly may be marked and associated with tenderness, splenomegaly, signs of liver failure and ascites. Systemic disturbances include fever and neutrophilic leucocytosis. The gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is the predominant abnormality. The AST generally exceeds the ALT, but both are only moderately raised. Values for aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) above 500 U/L suggest another disorder that may coexist with ALD, most often viral hepatitis or paracetamol (acetaminophen) toxicity.

Mild cases are common and typically manifest with abnormal serum biochemistry, and hepatomegaly. Severe alcoholic hepatitis is relatively rare and carries a short-term mortality of approximately 50%. The severity of alcoholic hepatitis can be assessed using a number of simple quantitative indices (Maddrey score, MELD Score, Combined Clinical and Laboratory Index). Of these, the Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF) is the simplest (Table 40.1).

TABLE 40.1 Using the Maddrey score to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis

|

Maddrey score = 4.6 × (prolongation of prothrombin time above control in seconds) + bilirubin (μmol/L)/17

|

Alcoholic cirrhosis

Alcoholic cirrhosis may present with fatigue, anorexia, nausea, malaise or weight loss but typically presents with complications such as portal hypertension leading to variceal bleeding and/or ascites, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma. Alcoholic cirrhosis is a recognised risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma but it is not clear that there is an association between alcohol abuse and hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis.

DETECTION OF ALCOHOL ABUSE

Several brief questionnaires have been validated for the detection of alcohol abuse (Table 40.2). If a screening test is positive, more detailed assessment is indicated.

TABLE 40.2 Screening questions for excessive alcohol consumption

| A positive response on screening indicates the need for further assesssment |

Laboratory markers such as gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) are only moderately sensitive and specific for drinking problems in general. In ALD, the GGT level is almost invariably elevated. However, elevated levels may also be seen in other liver diseases and with some drugs (notably anticonvulsants). The MCV is generally less sensitive and less specific than GGT. Combined assessment of MCV and GGT detects 70% of the alcohol-dependent population. The carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) test may be more specific than GGT, but the test is not widely available at present and there are false positives in any form of advanced liver disease. Several other laboratory parameters may be elevated, including uric acid, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. These are not adequately sensitive or specific for use as a screening test.

NATURAL HISTORY

Abstinence from alcohol consumption is the major factor influencing survival. In those who continue to drink, alcoholic hepatitis progresses rapidly to cirrhosis. The survival benefit with abstinence is less clear for advanced liver disease, as the outcome may be determined by irreversible liver damage and complications such as portal hypertension rather than by continuing alcohol consumption.

MANAGEMENT

Fatty liver and mild alcoholic hepatitis almost invariably recover with abstinence from alcohol. Severe disease is associated with poor outcomes and warrants specific treatment, but the available options are limited (Table 40.3).

Management of alcohol use disorder

How can abstinence be achieved?

Treatment for alcohol abuse is moderately effective. For non-dependent drinkers, brief intervention may be effective. It does not require specialised staff and can be done in 5–10 min. The FLAGS acronym summarises one approach (Table 40.4). Follow-up is recommended with repeated intervention if necessary.

| Feedback | The nature and extent of alcohol-related problems |

| Listen | To patient concerns |

| Advise | Patient clearly to reduce consumption |

| Goals | Negotiate clinically appropriate goals acceptable to the patient |

| Strategies | Specific suggestions to modify drinking |

For alcohol dependence, the initial step is to manage the risk of withdrawal. The risk is higher if there have been previous withdrawal episodes, and with more severe and longstanding alcohol dependence. Diazepam is usually the drug of choice, but in the presence of liver failure, active metabolites of diazepam can precipitate hepatic encephalopathy. In this setting, oxazepam is the preferred drug as it does not have active metabolites. Symptom-triggered treatment involves regular monitoring (every 1–6 hours depending on severity) with an alcohol withdrawal scale if hospitalised (AWS or the CIWA) and administration of a benzodiazepine according to the score (Table 40.5). This provides more intensive treatment when symptoms are severe and lessens the duration of treatment once symptoms settle. Benzodiazepines should not be used for more than 1 week due to the risk of dependence. All patients should receive thiamine initially parenterally, then orally until sustained abstinence is achieved.

TABLE 40.5 Typical regimen for alcohol withdrawal

| Score | Diazepam dose | Oxazepam dose |

| Low (AWS 0–3) | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate (AWS 3–5) | 10 mg | 30 mg |

| High (AWS >5) | 20 mg | 60 mg |

Repeat assessment 2–6-hourly depending on severity. All patients should receive adequate doses of thiamine.

Once withdrawal has settled, continuing management to prevent relapse to heavy drinking may be implemented by an interested general practitioner, if available, or via a specialist alcohol treatment service. Treatment options include counselling of various types, naltrexone, acamprosate, peer support and residential rehabilitation. There is no clear evidence to favour one treatment modality over the others. Naltrexone is an orally active opioid antagonist that reduces the psychological reward provided by alcohol, leading to reduced desire to drink. Naltrexone has hepatotoxic potential, typically at higher doses than are used routinely. Hepatic naltrexone clearance is reduced in cirrhosis, but no increased risk of hepatotoxicity has been reported. Acamprosate inhibits central nervous system N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and GABA transmission. Side effects are uncommon and mild and include diarrhoea, dizziness and pruritus. Acamprosate is not metabolised by the liver and its pharmacokinetics are not altered in liver failure. Disulfiram inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), leading to accumulation of acetaldehyde after alcohol consumption, which causes an aversive reaction with nausea and vomiting. Directly supervised treatment (by family member or health professional) may be very effective but unsupervised treatment is ineffective. It is occasionally hepatotoxic and is not recommended in severe liver disease. Pharmacotherapy is typically commenced once the patient is well enough to contemplate resumption of alcohol consumption and ideally before discharge from hospital. Counselling models include motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy, which can be offered for individuals, families or groups. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a peer fellowship that conceptualises ‘alcoholism’ as a medical disease that can be controlled by adopting a 12-step approach. The duration of abstinence correlates with the number of AA meetings attended. Residential rehabilitation services should be considered for severe cases with medical and social disintegration.

Monitoring alcohol intake

Monitoring alcohol intake by self-report provides adequate information in most cases. Alcohol may be measured in blood, breath or urine and positive results indicate consumption within the last few hours. Trace levels in blood (up to 0.01%) have been reported from endogenous ethanol production. In abstinent patients, levels of GGT fall with an apparent half-life of 2 weeks and are usually normal within 6 weeks. The MCV falls over several months and is insensitive to drinking relapse. Rising CDT levels have been reported to precede self-report of relapse.

Management of liver disease

Hospital admission is required for severe disease, complications and failed out patient management.

Pentoxifylline

Pentoxifylline is a dimethylxanthine derivative used for peripheral vascular disease because it decreases blood viscosity (via increasing erythrocyte deformity) and improves blood flow. It also attenuates tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) release and action and exerts an antifibrinogenic action. Pentoxifylline (400 mg t.d.s.) has recently been shown to improve short-term (4 week) survival in a prospective randomised controlled trial of 96 patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. This survival benefit was related to a significant decrease in the rate of development of hepatorenal syndrome. Replication of this result by other clinical units is required before its use can be confidently recommended. The only significant side effects were nausea, epigastric pain and vomiting, and these resolved soon after discontinuation of treatment. The drug is inexpensive and widely available. Use of this drug in patients with sepsis and active gastrointestinal bleeding has not been evaluated.