Alcohol

Abuse of alcohol (ethanol) is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality, far outstripping other drugs in its effects on the individual and on society. Alcohol is a drug with no receptor. The mechanisms by which it exerts its detrimental effect on cells and organs are not well understood, but the effects are summarized in Table 62.1.

Table 62.1

Effects of ethanol on organ systems

| System | Condition | Effect |

| CNS | Acute | Disorientation → coma |

| Chronic | Memory loss, psychoses | |

| Withdrawal | Seizures, delirium tremens | |

| Cardiovascular | Chronic | Cardiomyopathy |

| Skeletal muscle | Chronic | Myopathies |

| Gastric mucosa | Acute | Irritation, gastritis |

| Chronic | Ulceration | |

| Liver | Chronic | Fatty liver → cirrhosis, decreased tolerance to xenobiotics |

| Kidney | Acute | Diuresis |

| Blood | Chronic | Anaemia, thrombocytopenia |

| Testes | Chronic | Impotence |

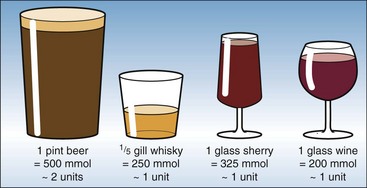

For clinical purposes alcohol consumption is estimated in arbitrary ‘units’ – one unit representing 200–300 mmol of ethanol. The ethanol content of some common drinks is shown in Figure 62.1. The legal limit for driving in the UK is a blood alcohol level of 17.4 mmol/L (80 mg/dL).

Metabolism of ethanol

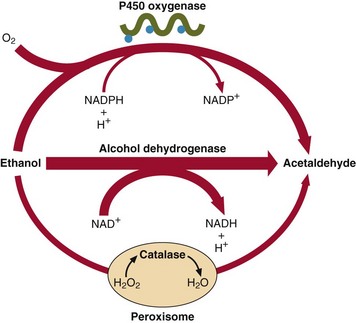

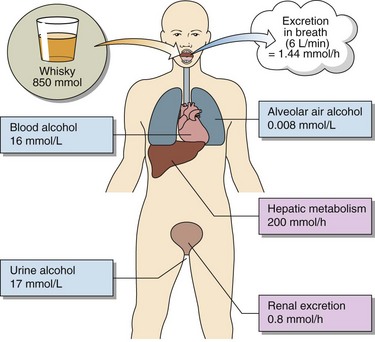

Ethanol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by two main pathways (Fig 62.2). The alcohol dehydrogenase route is operational when the blood alcohol concentration is in the range 1–5 mmol/L. Above this most of the ethanol is metabolized via the microsomal P450 system. Although the end product in both cases is acetaldehyde, the side effects of induced P450 can be significant. Ethanol metabolism and excretion in a normal 70 kg man is summarized in Figure 62.3.

Acute alcohol poisoning

The effects of ethanol excess fall into two categories:

those that are directly related to the blood alcohol concentration at the time, such as coma

those that are directly related to the blood alcohol concentration at the time, such as coma

those that are caused by the metabolic effects of continued high ethanol concentrations.

those that are caused by the metabolic effects of continued high ethanol concentrations.

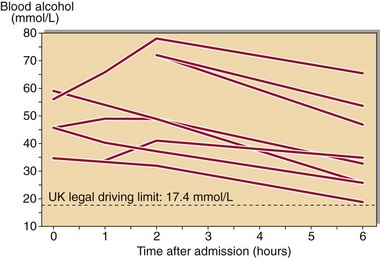

Recovery from acute alcohol poisoning is usually rapid in the absence of renal or hepatic failure, and is speeded up if hepatic blood flow and oxygenation is maximized. The elimination rate of ethanol is dose-related; at a level of 100 mmol/L it is around 10–15 mmol/hour. Ethanol concentrations in a group of chronic alcoholics admitted in coma with acute alcohol poisoning are shown in Figure 62.4.

Chronic alcohol abuse

impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus

impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus

cirrhosis of the liver with resultant decreased serum albumin concentration

cirrhosis of the liver with resultant decreased serum albumin concentration

Diagnosis of chronic alcohol abuse

Elevated γGT. This enzyme is increased in 80% of alcohol abusers. It is not a specific indicator as it is increased in all forms of liver disease and is induced by drugs such as phenytoin and phenobarbital.

Elevated γGT. This enzyme is increased in 80% of alcohol abusers. It is not a specific indicator as it is increased in all forms of liver disease and is induced by drugs such as phenytoin and phenobarbital.

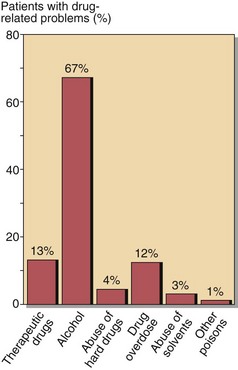

Admission rates to hospital with alcohol-related diseases are high, and since the diagnosis is sometimes unsuspected, it should always be considered when carrying out an initial examination (Fig 62.5).