CHAPTER 75 AIRWAY MANAGEMENT IN THE TRAUMA PATIENT: HOW TO INTUBATE AND MANAGE NEUROMUSCULAR PARALYTIC AGENTS

Injury is the leading cause of death in persons between the ages of 1 and 45 years in the United States and the third leading cause overall. Airway compromise is a common cause of death or severe morbidity in trauma victims. Management of the airway is a fundamental skill in trauma medicine. Obstruction of the airway has been reported in two-thirds of patients who die in the prehospital setting when death was not inevitable. Airway care is a cornerstone of resuscitation and is the first priority for patients both in the prehospital setting and in the emergency room (ER).

AIRWAY CONSIDERATIONS IN THE TRAUMA PATIENT

There is an increased risk for awareness among trauma patients during airway manipulation and surgery. The incidence of awareness in the general adult patient population undergoing anesthesia is 0.1%–0.2%. Approximately 50% of these patients will have some psychological impact from their experience, and the most severe reaction is full-blown post-traumatic stress syndrome. The incidence of awareness is reported to be higher among trauma patients. These patients often have such hemodynamic instability that they tolerate only very light levels of anesthesia. It is, therefore, good practice to always consider giving amnesia-inducing drugs when neuromuscular blocking agents are used. To be paralyzed and unable to communicate is an extremely traumatic experience.

EVALUATION OF AIRWAY AND RESPIRATORY FUNCTION

In recent years, the development of classification systems to predict difficult intubations has reduced the incidence of airway complications in patients undergoing elective surgery. The Mallampati classification of the airway (see page 59) is commonly used and is based on assessment of tongue size in relation to other pharyngeal structures. The I to IV scoring scale predicts difficulty of intubation. The atlanto-occipital joint extension test measures the ability to extend the neck and, consequently, the ability to align pharyngeal and laryngeal axes to accommodate intubation. Measurements of the thyro-mental distance, sterno-mental distance, mandibulo-hyoid distance and inter-incisor distance are also helpful in evaluating the airway.

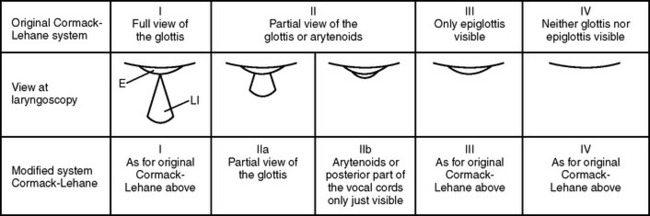

To provide high specificity and sensitivity for successful intubation and to assess the level of difficulty of an endotracheal intubation, several tests must be performed. These tests are usually correlated to the visualization of laryngeal structures and vocal cords. The gold standard for classifying the degree of exposure to the larynx entrance is the description by Cormac and Lehane (Figure 1). Grades III and IV are associated with difficult intubation. The dilemma is that all these tests are difficult to utilize in the trauma patient for many reasons, including an immobilized neck. Thus, alternative scoring systems such as the LEMON method have been proposed.

The LEMON method was developed by the U.S. National Emergency Airway Management Course and has a maximum score of 10 points, calculated by assigning 1 point for each criterion (Table 1). It has been demonstrated that an airway assessment score based on the LEMON criteria is helpful in predicting difficult intubation in the ER. The LEMON test is designed to be a quick and easy-to-use assessment tool. A poor laryngoscopic view is more common, for example, among patients with large incisors, a reduced inter-incisor distance, and a reduced thyroid-to-floor-of-mouth distance.

| Physical Sign | Less Difficult Airway | Indicators of Difficult Airway |

|---|---|---|

| Look at exterior | No face or neck pathology | Face or neck pathology, obesity, and so on |

| Evaluate the 3-3-2 rule | Mouth opening >3F | Mouth opening <3F |

| Hyoid–chin distance >3F | Hyoid–chin distance <3F | |

| Thyroid cartilage–mouth floor distance >2F | Thyroid cartilage–mouth floor distance <2F | |

| Mallampati | Classes I and II | Classes III and IV |

| Obstruction | None | Obstruction within or surrounding upper airway |

| Neck mobility | Normal extension and flexion | Limited range of motion |

F, Finger-breadths.

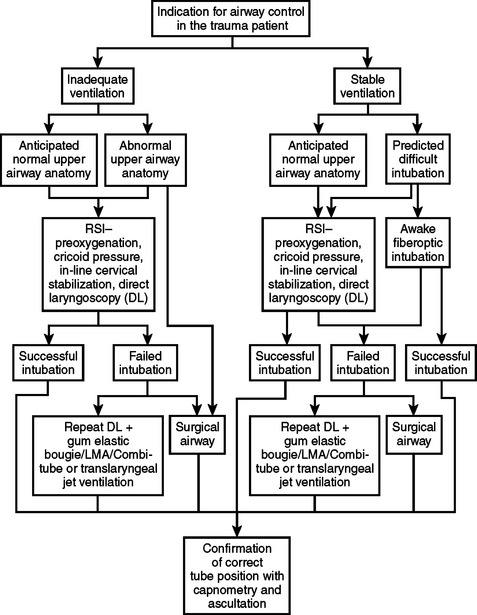

Planning an approach is the final step of the assessment (Figure 2). The team should then proceed with the airway management plan. When the patient can maintain adequate oxygenation and ventilation, and time permits, it may be beneficial to transport the patient to the OR which normally has better equipment and resources than the ER. In other situations, the right decision may be to immediately establish a surgical airway with the patient breathing spontaneously.

INDICATIONS FOR INTUBATION AND CONTROLLED VENTILATION

Trauma victims with cardiac arrest have a higher survival rate if early intubation is performed.

INDUCTION AGENTS AND MUSCLE RELAXANTS

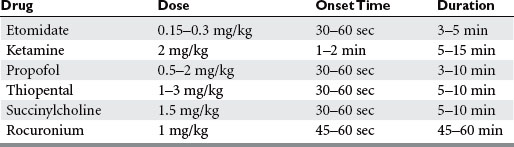

Muscle relaxants are used to create conditions that facilitate the intubation procedure. The larynx, for example, must be visualized as optimally as possible, and muscle tone suppression is integral to creating this condition. To help prevent hypoxemia and hypercapnia, a short onset time for muscle paralysis is important. Today, succinylcholine and rocuronium are the two drugs available that fulfill this criterion. Succinylcholine has some undesirable side effects, and substantial research has been underway to find an alternative drug. So far, however, no superior replacement has been introduced on the market, although promising drugs are under investigation. The current alternative to succinylcholine is rocuronium, but it does not match the short onset and short duration of succinylcholine.

INTUBATION TECHNIQUES

For this approach, drugs are injected at predetermined doses. Taking into consideration that the decisions regarding medications must often be made within seconds of the patient’s arrival, it is fundamental to have a thorough knowledge about drug actions in order to tailor the choice and dose and to avoid causing harm and circulatory instability (Table 2).

The induction agent is injected as a bolus and is immediately followed by the muscle relaxant. When the patient starts to lose consciousness, one assistant will hold the patient’s neck in in-line stabilization, and a second assistant will apply cricoid pressure using Sellick’s maneuver to compress the esophagus between the cricoid cartilage and C6, prohibiting the regurgitation of stomach contents during airway manipulation. It is permissible to open the cervical collar to facilitate intubation as long as strict attention is maintained to prevent cervical movements.

Arne J, et al. Preoperative assessment for difficult intubation in general and ENT surgery: predictive value of a clinical multivariate risk index. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80(2):140-146.

Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK. Clinical Anesthesia, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

Bell RM, Krantz BE, Weigelt JA. ATLS: a foundation for trauma training. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(2):233-237.

Caplan RA, et al. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1990;72(5):828-833.

Copass MK, et al. Prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation of the critically injured patient. Am J Surg. 1984;148(1):20-26.

Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984;39(11):1105-1111.

Cormack RS, et al. Laryngoscopy grades and percentage glottic opening. Anaesthesia. 2000;55(2):184.

Crosby ET, et al. The unanticipated difficult airway with recommendations for management. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45(8):757-776.

Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). Guidelines for Emergency Tracheal Intubation Immediately Following Traumatic Injury. Allen-town, PA: Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, 2002.

Foley LJ, Ochroch EA. Bridges to establish an emergency airway and alternate intubating techniques. Crit Care Clin. 2000;16(3):429-444. vi

Ghoneim MM. Awareness during anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(2):597-602.

Hussain LM, Redmond AD. Are pre-hospital deaths from accidental injury preventable? BMJ. 1994;308(6936):1077-1080.

Ivy ME, Cohn SM. Addressing the myths of cervical spine injury management. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;15(6):591-595.

Langeron O, et al. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(5):1229-1236.

Mallampati SR, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;32(4):429-434.

Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(2):607-613.

Morton T, Brady S, Clancy M. Difficult airway equipment in English emergency departments. Anaesthesia. 2000;55(5):485-488.

O’Callaghan-Enrigh S, Finucane BT. Anesthetizing the airway. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 1995;13(2):325-336.

Osterman JE, et al. Awareness under anesthesia and the development of post-traumatic stress disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(4):198-204.

Peterson GN, et al. Management of the difficult airway: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(1):33-39.

Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(3):597-602.

Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(5):1269-1277.

Reed MJ, Dunn MJ, McKeown DW. Can an airway assessment score predict difficulty at intubation in the emergency department? Emerg Med J. 2005;22(2):99-102.

Rose DK, Cohen MM. The airway: problems and predictions in 18,500 patients. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41(5 Pt 1):372-383.

Sakles JC, et al. Airway management in the emergency department: a one-year study of 610 tracheal intubations. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31(3):325-332.

Sebel PS, et al. The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States study. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(3):833-839.

Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2-S12.

Tayal VS, et al. Rapid-sequence intubation at an emergency medicine residency: success rate and adverse events during a two-year period. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(1):31-37.

Trunkey DD. Trauma: accidental and intentional injuries account for more years of life lost in the U.S. than cancer and heart disease. Among the prescribed remedies are improved preventive efforts, speedier surgery and further research. Sci Am. 1983;249(2):28-35.

Walls RM. Management of the difficult airway in the trauma patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(1):45-61.