Chapter 34 Airway Management in the Intensive Care Unit*

Noninvasive Ventilation

Patients with respiratory failure and preserved airway reflexes may benefit from NIV. The rationale for this application, most commonly seen in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), is that NIV may reduce the work of breathing and help to correct hypercapnic or hypoxic respiratory failure. NIV is contraindicated, however, with cardiovascular or respiratory instability, compromised ability to handle secretions, aspiration risk, or inability to tolerate a tight-fitting face mask (see Chapter 33 on NIV).

Airway Assessment

Predictors of Difficult Intubation

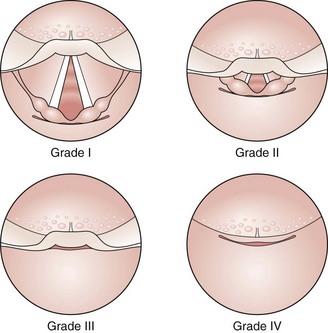

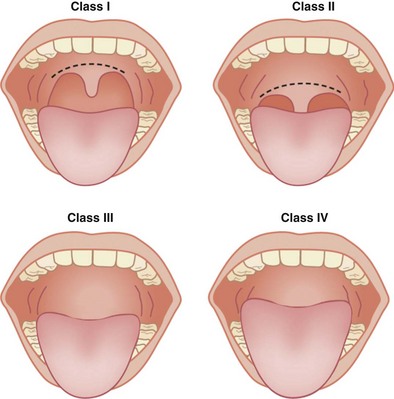

Examination of the patient should determine the following: ability to protrude the mandible, range of neck movement, atlantooccipital flexion and extension, interincisor distance (less than 3 cm indicates a high likelihood of difficulty), and modified Mallampati test (Figure 34-1). Other predictors of difficult intubation include thyromental distance of less than 7 cm (Patil’s test) and obesity. Further investigations when indicated could include the view of the larynx obtained at nasal endoscopy, which may predict the view at laryngoscopy; chest radiographs, which may show tracheal deviation or mediastinal masses; and CT scans, which may be useful when abnormal anatomy is suspected—for example, in association with tracheal stenosis.

Figure 34-1 Mallampati test to classify view of the pharynx. For this test, the patient is asked to protrude the tongue fully while opening the mouth maximally, with the head in the neutral position. Class I: The pharyngeal pillars, soft palate, and uvula are visible. Class II: Only the soft palate and uvula are visible. Class III: Only the soft palate is seen. Class IV: Only the hard palate is seen. Mallampati class correlates with Cormack and Lehane grade for the view at laryngoscopy (see Figure 34-5). Increasing class suggests more difficult laryngoscopy.

Aspiration Risk

Aspiration of gastric contents can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Evidence suggests that reducing gastric volume and increasing pH of gastric contents will limit the risk of disorders associated with aspiration. Acid aspiration may lead to a chemical pneumonitis, but aspiration of food particles can result in physical obstruction of the bronchial tree with secondary bacterial pneumonia (Box 34-1 and Table 34-1).

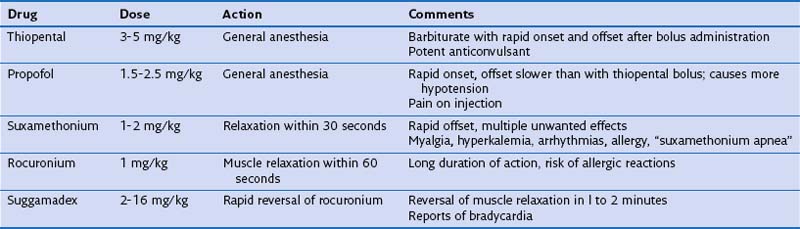

| Drug Class | Specific Agent | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Histamine H2 receptor antagonists | Ranitidine 50 mg IV | Increases pH and decreases gastric volume |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Omeprazole 40 mg IV | Irreversibly binds H+/K+-ATPase; increases pH and decreases gastric volume |

| Nonparticulate antacids | 0.3 M sodium citrate, 10 mL | Neutralizes gastric pH but increases volume Very effective at increasing gastric pH if given within 30 minutes |

| Prokinetics | Metoclopramide 10 mg | Reduces gastric volume |

Endotracheal Intubation with Muscle Relaxation

Positioning

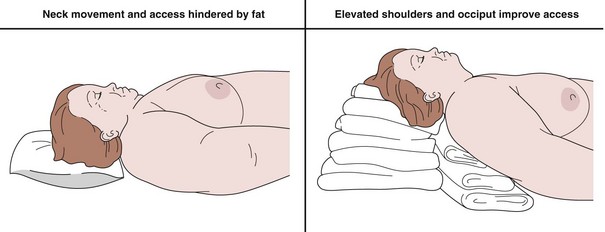

Putting the patient in the optimal position is the first and most important step. Appropriate positioning allows good access to the airway and allows efficient preoxygenation. Other advantages include improvement of the laryngoscopic view and, with the head held slightly up, a reduced risk for aspiration of gastric contents. The “head-up” position also increases functional residual capacity by allowing better diaphragmatic excursion, thereby increasing oxygen reserves. The patient should be positioned with the neck flexed on a pillow, but with the head extended, so long as cervical spine injury is not suspected. Positioning is of particular importance in the obese patient (Figure 34-2).

Preoxygenation

Before induction of anesthesia, the patient should be fully preoxygenated. The patient breathes 100% oxygen through a tight-fitting face mask for 3 minutes. In an emergency, five vital capacity breaths of 100% oxygen can be used in an attempt to fill the functional residual capacity lung compartment with oxygen, thereby significantly raising the alveolar PO2. This step prolongs the time to desaturation after the onset of apnea, affording the operator significant time to manage the airway safely (Table 34-2).

Cricoid Pressure

A major concern with an emergency intubation is the risk of aspiration of gastric contents. Cricoid pressure can be applied to prevent passive regurgitation of stomach contents, with subsequent airway soiling. The assistant exerts firm pressure (equivalent to 30 newtons [N] of backward pressure) on the cricoid cartilage to compress the esophagus against the body of the sixth cervical vertebra as the level of consciousness diminishes (Figure 34-3). Cricoid pressure should be removed only if the patient actively vomits (associated with risk for esophageal rupture) or in specific instances of inability to oxygenate (see the difficult intubation algorithm presented in Figure 34-7).

Equipment

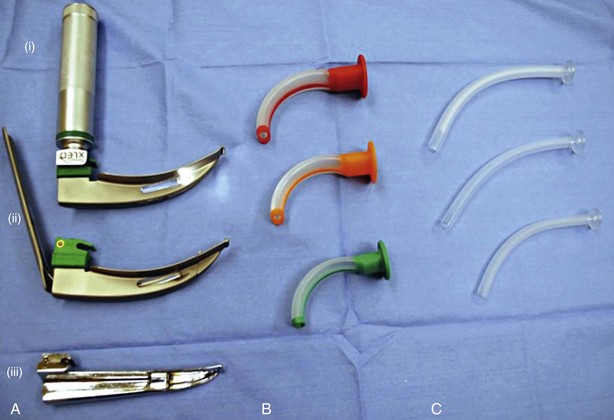

The most common laryngoscope blade used for intubation in adults is the curved Macintosh blade (Figure 34-4). This is inserted into the right side of the mouth to displace the tongue laterally. The tip of the blade sits in the vallecula and is lifted forward to elevate the epiglottis and expose the laryngeal inlet. The McCoy blade is a variant of the Macintosh and has a hinged tip to further lift the epiglottis. A straight Miller blade can be useful in adults in whom the epiglottis is difficult to displace. This blade is inserted further to directly lift the epiglottis. Where laryngoscopy may be difficult a video laryngoscope can be used. There are now a variety of different models available on the market (Figure 34-5). They require less manipulation of the cervical spine and allow intubation in a seated position, reducing the aspiration risk (Videos 1-4). ![]() Awake fiberoptic intubation may be used were visualization of the larynx may be difficult by other means or if access to the mouth is restricted.

Awake fiberoptic intubation may be used were visualization of the larynx may be difficult by other means or if access to the mouth is restricted.

Laryngeal Anatomy

The view of the laryngeal inlet obtained at direct laryngoscopy can be graded in accordance with the Cormack and Lehane classification (Figure 34-6). Grade I and grade II views indicate straightforward intubation. A grade III view frequently necessitates the use of a gum elastic bougee to “railroad” the endotracheal tube (ETT) into position, whereas a grade IV view often will mandate a different strategy to achieve successful intubation.

Rescue Techniques

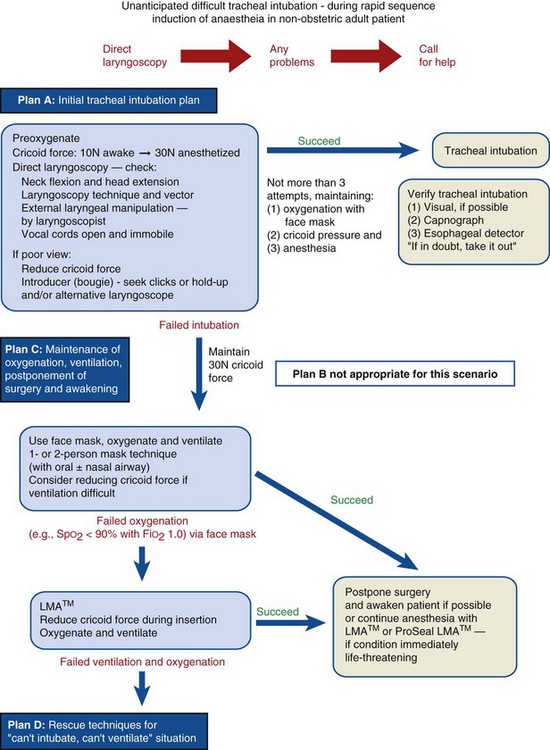

Whenever the decision is taken to intubate, the physician should always have an alternative plan to use if any difficulties are encountered. In the United Kingdom, the difficult intubation algorithm produced by the Difficult Airway Society is used (Figure 34-7).

Laryngeal Mask Airway

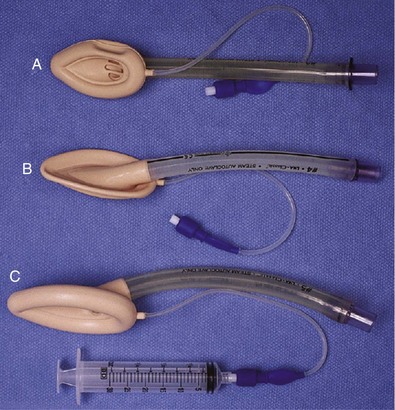

The LMA is extremely useful in clinical situations in which mask ventilation would be difficult or when intubation is impossible. It can be used to maintain oxygenation while a plan for definitive airway control is made, or it can be used as a conduit for access to the larynx. A fiberoptic scope can be inserted through the LMA and an ETT passed over the scope into the trachea. The intubating LMA is specifically designed to facilitate tracheal intubation; special features include an epiglottic elevating bar facilitating access to the trachea. It can be useful in patients in whom neck movement is limited (Figure 34-8).

surgical airways

Cricothyroidotomy

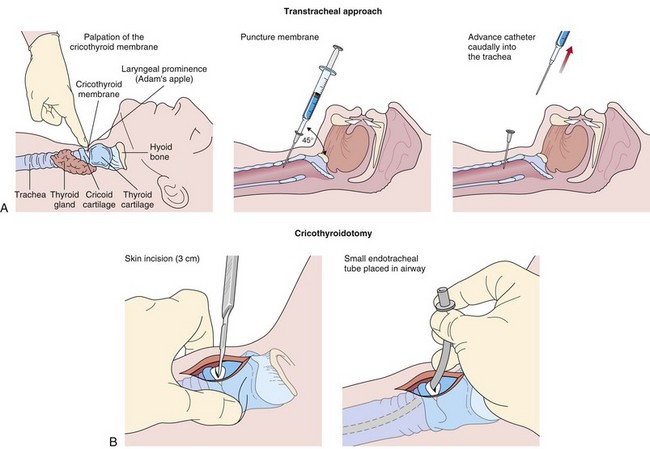

In situations in which it is not possible to either intubate or ventilate the patient, an emergency cricothyroidotomy should be performed (Figure 34-9). The cricothyroid membrane is an avascular membrane joining the thyroid cartilage to the cricoid cartilage. A purpose made kink-resistant cannula can be inserted through the cricothyroid membrane into the trachea, and then the patient is jet ventilated through this tube. Larger cricothyroidotomy devices can be used that allow the patient to be ventilated in a conventional fashion. Surgical cricothyroidotomy requires more skill and involves dissection down to the cricothyroid membrane, followed by insertion of an appropriately sized endotracheal tube (6-mm inner diameter) into the trachea. Cricothyroidotomy is associated with multiple complications, including airway loss, esophageal trauma, bleeding, false passage formation, pneumothorax, and surgical emphysema.

Tracheostomy

Surgical tracheostomy requires a skilled surgeon. It can be performed to sidestep impending upper airway loss in the awake patient with use of local anesthesia. It is not suitable as a rescue technique because it is time-consuming. Boxes 34-2 and 34-3 lists the indications for and possible complications of surgical tracheostomy.

Aitkenhead AR, Smith G, Rowbotham DJ. Textbook of anaesthesia, ed 5. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Al-Shaikh B, Stacey S. Essentials of anaesthetic equipment, ed 3, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2007.

Cook T, Woodall N, Frerk C, Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. London: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Lim MS, Hunt-Smith JJ. Difficult airway management in the intensive care unit: practical guidelines. Crit Care Resusc. 2003;5:8–9.

Savva D. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:149–153.