Airway Care

I Use of Artificial Airways (Modified from AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: Management of Airway Emergencies, 1995)

1. Conditions requiring management of the airway generally are impending or actual

2. Specific conditions include but are not limited to

a. Airway emergency before endotracheal intubation

b. Obstruction of the artificial airway

f. Cardiopulmonary arrest and unstable dysrhythmia

h. Severe allergic reactions with cardiopulmonary compromise

j. Sedative or narcotic drug effect

k. Foreign body airway obstruction

3. Conditions requiring emergency tracheal intubation include, but are not limited to

b. Traumatic upper airway obstruction (partial or complete)

c. Accidental extubation of the patient unable to maintain adequate spontaneous ventilation

d. Obstructive angioedema (edema involving the deeper layers of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and mucosa)

e. Massive uncontrolled upper airway bleeding

f. Coma with potential for increased intracranial pressure

g. Infection-related upper airway obstruction (partial or complete)

h. Epiglottitis in children or adults

4. Neonatal or pediatric specific

b. Severe adenotonsillar hypertrophy

f. Obstruction from abnormal laryngeal closure caused by arytenoid masses

h. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

i. Presence of thick and/or particulate meconium in amniotic fluid

5. Conditions in which endotracheal intubation may not be possible and in which alternative techniques may be used include, but are not limited to

1. Failure to establish a patent airway

2. Failure to intubate the trachea

3. Failure to recognize esophageal intubation

4. Unrecognized bronchial intubation

5. Upper airway trauma, laryngeal and esophageal damage

12. Endotracheal tube (ETT) problems (e.g., cuff perforation, cuff herniation, pilot tube-valve incompetence, tube kinking during biting, tube occlusion, and inadvertent extubation)

17. Hypotension and bradycardia caused by vagal stimulation

18. Hypertension and tachycardia

22. Specific problems resulting from nasal intubation (e.g., nasal damage including epistaxis, tube kinking in the pharynx, sinusitis, and otitis media)

23. Tracheal damage (e.g., tracheoesophageal fistula, tracheal innominate fistula, tracheal stenosis, and tracheomalacia)

24. Laryngeal damage with consequent laryngeal stenosis, laryngeal ulcer, granuloma, polyps, or synechiae

25. Specific problems resulting from surgical cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy (e.g., stomal stenosis, innominate erosion)

26. Specific problems resulting from needle cricothyrotomy (e.g., bleeding at the insertion site with hematoma formation, subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema, and esophageal perforation)

II General Classification of Artificial Airways

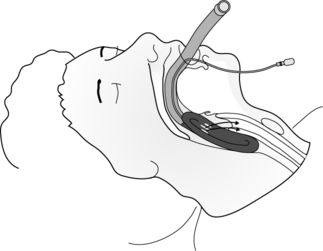

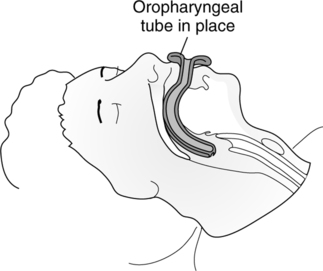

A Oropharyngeal airway (Figure 38-1)

1. Used to relieve upper airway obstruction by maintaining the base of the tongue off the posterior wall of the oral pharynx

2. Used to prevent inadvertent laceration of the tongue in the incoherent or seizuring patient

3. May be used as a bite block with oral ETTs

4. To insert the oropharyngeal airway, turn the airway 180 degrees from its normal position, insert it into the patient’s mouth, and when it is at the back of the tongue rotate it 180 degrees to its normal position so that the tip is behind the tongue and facing the larynx. A tongue depressor may be used to facilitate insertion of the airway.

5. Poorly tolerated in alert patient because of stimulation of gag reflex

1. It is used to relieve upper airway obstruction caused by the tongue or soft palate falling against the posterior wall of the pharynx.

2. To insert the nasal airway lubricate the outside of the nasal airway with water-soluble lubricant, insert it into the nares, and advance gently until the tip is behind the tongue just above the epiglottis.

3. Suctioning via this airway is less traumatic than nasal suctioning.

4. It is better tolerated than an oropharyngeal airway.

5. It should be alternated every 24 hours between right and left nares to minimize complications.

6. Sinusitis, otitis media, and nasal necrosis are possible complications of its use.

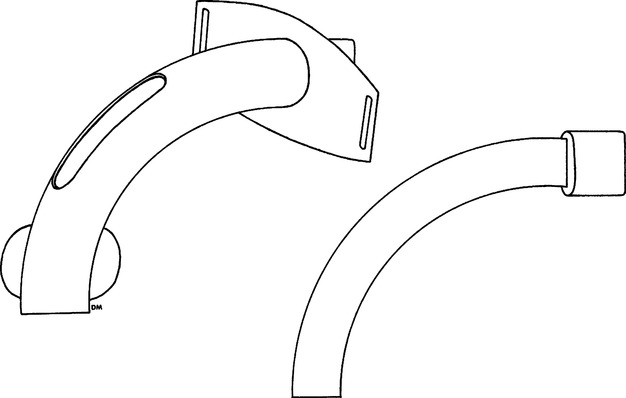

1. The LMA may be used to manage the airway during anesthesia or as an emergency airway when the airway is difficult to intubate.

2. The LMA is a tube with a small, inflatable mask at the distal end.

3. The LMA is inserted deep into the oropharynx with the tip of the mask just above the esophageal sphincter. After insertion the cuff of the mask is inflated. The opening in the mask should face the laryngeal opening when inserted properly (Figure 38-2).

4. Available in sizes 3, 4, and 5 for adults

1. Advantages when compared with nasotracheal tubes

a. It is easy to insert and is the airway of choice in an emergency.

b. A larger-diameter tube can be inserted orally than by the nasal route.

c. Sinusitis and otitis media are not problems.

d. The angle of curvature is less acute than with nasal tubes; it is easier to suction.

e. Generally there is less resistance to gas flow, and less work of breathing is imposed.

2. Problems associated with orotracheal tubes

a. They are poorly tolerated in conscious and semiconscious patients.

b. They are difficult to stabilize and may be easily dislodged.

c. Inadvertent extubation is common.

d. A bite block may be necessary to prevent biting of tube.

e. Vagal stimulation may cause bradycardia and hypotension.

g. They require a laryngoscopy during insertion.

h. Patients are unable to mouth words.

j. There is a potential for laryngeal pathology.

k. The tip of the tube moves when the patient’s head position changes.

1. Advantages over orotracheal tube for long-term intubation

b. May be better tolerated by some patients

c. May be inserted blindly (laryngoscopy is unnecessary in most cases)

d. Oral hygiene is easily accomplished.

e. The patient is able to mouth words.

f. Attachment of equipment is easier and safer; there is less torque on the trachea.

2. Problems associated with nasotracheal tubes

a. The tip of the tube moves when the patient’s head position changes.

b. Pressure necrosis in area of the alae nasi may occur.

c. Sinus drainage may be obstructed, and acute sinusitis may result.

d. Eustachian tube drainage may be obstructed, and otitis media may result.

e. The incidence of vocal cord damage after 3 to 7 days (also seen with oral ETTs) increases.

f. Vagal stimulation is possible, but it occurs less frequently than with the oral ETT.

g. Skilled personnel are necessary for placement.

h. The nasal passage limits the tube size; a tube at least 0.5 mm ID smaller than the oral route is required.

i. The angle of curvature is acute; the resistance to gas flow is increased; there is difficulty in suctioning; and the work of breathing is increased when compared with an orotracheal tube in the same patient.

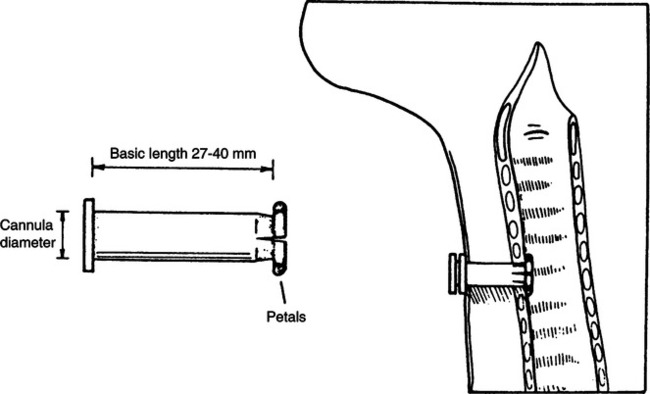

1. The size, length, and shape of a tracheostomy tube vary depending on the manufacturer and style of the tube.

2. Tracheostomy tube shapes are curved, angled, or extra long (Figure 38-3).

3. Careful consideration of the anatomy of each patient when choosing the brand and size of a tracheostomy tube may aid in preventing future complications.

4. Most tracheostomy tubes are sized according to ID in millimeters.

a. There are no complications with the upper airway or glottis.

d. The tracheostomy tube is the best tolerated of all airways.

e. The patient is able to mouth words, and talking or fenestrated tubes are available.

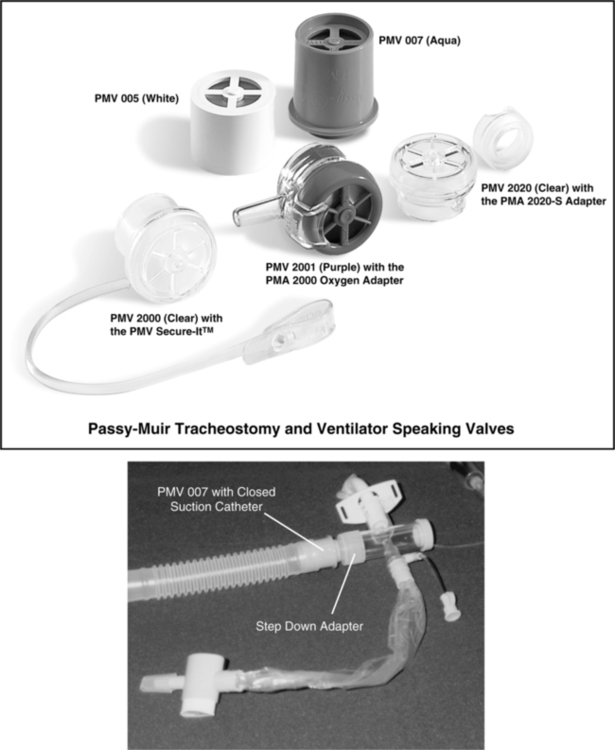

f. A speaking valve may be applied to either a fenestrated or a standard tracheostomy tube with the cuff deflated and the inner cannula removed (if present) so the patient can speak.

6. Problems associated with tracheostomy tubes

7. Frequent and routine changing of tracheostomy tubes is unnecessary if the airway is functioning properly and is properly humidified.

8. If a stomal infection develops frequent tracheostomy care using aseptic technique and changing of soiled dressings is recommended. Changing the tracheostomy tube may also be necessary.

G Percutaneous dilational tracheostomy (PDT) tubes are inserted by a relatively new procedure performed at the bedside.

1. A small incision is made in the neck and trachea, and the opening is dilated with special dilators until the desired size tube fits into the incision.

2. Advantages when performed properly as compared with surgical tracheostomy are

b. No need to move high-risk patients

c. General anesthesia not required

d. Decreased incidence of pneumothorax, bleeding, and stenosis

e. Stoma closes quickly after decannulation with less scar tissue formed

a. If inadvertent decannulation occurs before maturation of tracheostomy tract (2 weeks), reinsertion may lead to complications such as bleeding and tracheal trauma. Oral intubation is recommended in this case.

b. Should not be performed on patients who are morbidly obese, have burns to the neck, have bleeding disorders, have anatomic abnormalities of the trachea or cervical region, or had a previous tracheostomy

1. Routinely used for infants and small children

2. In adults primarily used for patients who require frequent suctioning but do not require mechanical ventilation

3. Should not be used for patients who are unable to protect their airways and prevent aspiration.

I Fenestrated tracheostomy tube (Figure 38-4)

1. Fenestration(s) may be located in the outer cannula only or in both cannulas, depending on the brand of tube.

2. The inner cannula is similar in design to the inner cannula of a nonfenestrated tracheostomy tube.

3. Proper procedure when capping the tube to allow a patient to speak includes

a. Suctioning the trachea and oropharynx

c. Deflation of cuff while positive pressure is applied to direct any pooled secretions above the cuff up and out of the airway into the oropharynx

d. Suction the oropharynx again.

e. Cap the outer cannula with the cap or a speaking valve such as the Passy-Muir valve (PMV) (Figure 38-5).

f. Assess patient for adequate flow through upper airway with no stridor present.

4. The patient must ventilate via the upper airway through the fenestration(s) in the cannula of the tracheostomy tube and around the tube.

5. Problems associated with the fenestrated tube include

a. Possible formation of granular tissue at site of fenestration when fenestration(s) is improperly positioned

6. Commercial fenestrated tubes are available from several manufacturers; however, these do not always fit properly.

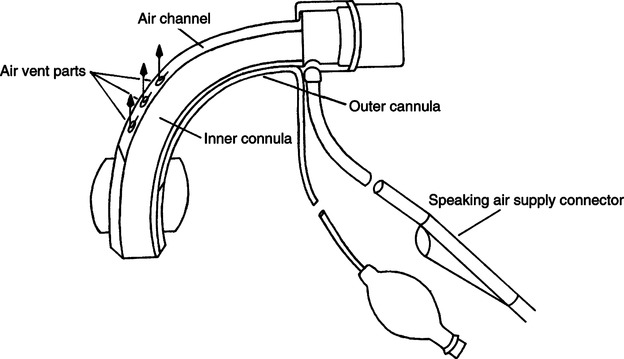

J Talking tracheostomy tube (Figure 38-6)

1. Is designed to allow the patient to verbalize when the cuff is inflated

2. It functions by directing secondary gas flow through ports in the tube above the patient’s cuff, allowing gas to move past the vocal cords while maintaining ventilation via the airway.

3. The ID of the airway is smaller than the standard tube of the same size.

K Tracheal button (Figure 38-7)

1. Used to maintain patency of the tracheal stoma

2. The inner lip of the button lies on the internal anterior tracheal wall, and the outer lip lies on the tissue of the neck.

3. The tracheal button allows the patient to ventilate completely from the upper airway without tracheal obstruction.

4. In an emergency the patient may be suctioned via the tracheal button.

III Extubation or Decannulation

A Indications for extubation (Modified from AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: Removal of the Endotracheal Tube, 1999)

1. When the airway control afforded by the ETT is deemed to be no longer necessary for the continued care of the patient, the tube should be removed.

2. The patient generally should be capable of maintaining a patent airway and adequate spontaneous ventilation and should not require high levels of positive airway pressure to maintain normal arterial blood oxygenation.

3. Patients in whom further medical care is considered (and explicitly declared) futile may have the ETT removed despite continuing indications for the artificial airway.

4. Acute artificial airway obstruction mandates immediate ETT removal if the obstruction cannot be cleared rapidly. Reintubation or other appropriate techniques to reestablish the airway must be used to maintain effective gas exchange (i.e., surgical airway management).

1. There are no absolute contraindications to extubation.

a. However, some patients may require reintubation, positive pressure ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure, noninvasive ventilation, or high inspired oxygen fraction to maintain acceptable gas exchange after extubation.

b. Airway protective reflexes are usually depressed immediately and for some time after extubation; therefore measures to prevent aspiration should be considered.

1. Hypoxemia after extubation may result from, but is not limited to

a. Failure to deliver adequate inspired oxygen fraction through the natural upper airway

b. Acute upper airway obstruction

c. Development of postobstruction pulmonary edema

2. Hypercapnia after extubation may be caused by, but is not limited to

a. Upper airway obstruction resulting from edema of the trachea, vocal cords, or larynx

b. Respiratory muscle weakness

3. Death may occur when medical futility is the reason for removing the ETT.

D Procedure for extubation includes

1. Suctioning the trachea and oropharynx

2. Deflation of cuff while positive pressure is applied to direct any pooled secretions above the cuff up and out of the airway into the oropharynx

3. Suctioning the oropharynx again

4. Listening for an audible leak around the tube with the cuff fully deflated

5. Removing the tube, preferably as the patient takes a deep breath

E Decannulation is the removal of a tracheostomy tube.

a. The patient generally should be capable of maintaining a patent airway and adequate spontaneous ventilation and should not require high levels of positive airway pressure to maintain normal arterial blood oxygenation.

2. Before decannulation the patient’s ability to swallow and protect the airway should be assessed.

3. A simple swallowing test may be done at the bedside using food coloring.

a. With the tracheostomy tube cuff deflated, have the patient swallow a small amount of ice chips or water colored with food coloring.

b. Tracheal suction the patient, and inspect the secretions for any coloration.

c. The test is useful if positive (coloration is present) because it demonstrates that the patient is unable to protect the airway and should not be decannulated. However, false-negative results can occur.

4. Procedure for decannulation is the same as for extubation.

5. A sterile, occlusive dressing should be applied over the stoma.

IV Laryngotracheal Complications of Endotracheal Intubation

A Sore throat and/or hoarse voice

B Glottic or subglottic edema as evidenced by stridor

C Tracheal injury: Ulceration, granuloma, malacia, or stenosis

A Administration of racemic epinephrine or dexamethasone may reverse or prevent glottic or subglottic edema.

B Until the edema decreases administration of Heliox may decrease the work of breathing and improve oxygenation when there is partial airway obstruction caused by glottic or subglottic edema.

C If symptoms of glottic or subglottic edema persist, reintubation may be necessary.

C Lateral tracheal wall pressures

1. Greater than 30 mm Hg causes cessation of arterial blood flow.

D Cuff pressures ideally should be maintained at 20 to 25 mm Hg to maintain tracheal capillary blood flow and prevent aspiration.

E Effects of high lateral tracheal wall pressures and sequence of tracheal changes

F Additional factors predisposing to tracheal damage

1. High peak airway pressure or positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) requiring higher cuff pressures

2. Too small or too large a cuff in relation to tracheal size

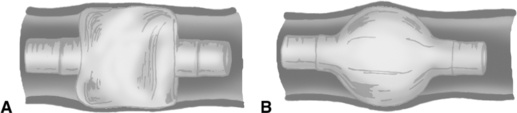

G High-volume, low-pressure vs. low-volume, high-pressure cuffs (Figure 38-8)

1. High-volume, low-pressure cuffs are the cuffs of choice for long-term airway maintenance.

1. Bivona foam cuff (Kamen-Wilkinson cuff)

a. Made of polyurethane foam with a silicone covering

b. Inflated by atmospheric pressure

c. No positive pressure is added to cuff.

d. Minimum pressures normally are applied to the tracheal wall.

e. Deflation of the cuff with a syringe before insertion allows reexpansion by atmospheric pressure.

f. This cuff may not form a complete seal in the trachea of some patients.

b. Facilitates insertion of the tube through a tight stoma

c. When deflated it collapses tight to the shaft of the tube; therefore it functions like an uncuffed tube, allowing the use of the upper airway for speaking and/or easier swallowing.

d. May be inflated for short periods to protect the airway from aspiration and/or provide an airway seal for ventilatory support

1. Minimal leak technique: Cuff volume maintains the seal except at maximum inspiratory pressure.

a. Insert enough air into the cuff until no leak is present.

b. While positive pressure is applied to the airway, withdraw air from the cuff until a slight leak develops. The leak should not be so great as to overcome the purpose of the cuff.

2. Minimal occluding volume technique: A minimal volume of gas is required to maintain the airway seal at peak positive pressure during inspiration.

a. Insert enough air to prevent any leak.

b. Withdraw gas during inspiration until a leak occurs.

c. Carefully inflate until the gas leak is stopped at peak inspiratory pressure.

d. There is less risk of aspiration of pharyngeal secretions than with the minimal leak technique.

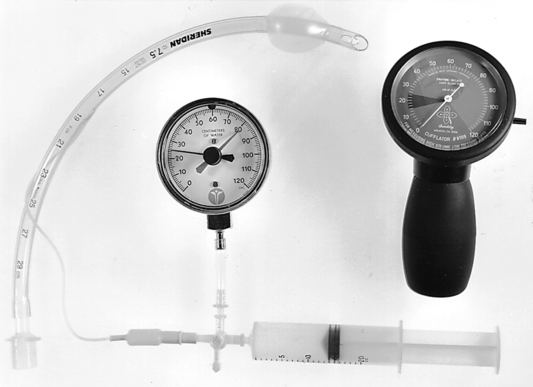

3. Monitoring of cuff pressures and volumes

a. A pressure monitor is used to evaluate actual intracuff pressure (Figure 38-9).

b. It is important to monitor intracuff pressures routinely and especially if high peak airway pressures are necessary or if high levels of PEEP are used.

c. If the minimal occluding volume technique is used, cuff pressures should be monitored frequently. A 1- to 2-ml increase in cuff volume can cause a precipitous increase in intracuff pressure.

d. Actual cuff pressures should be monitored and recorded routinely with ventilator checks or oxygen therapy equipment checks.

e. Cuff volumes should be monitored less frequently. Frequent deflation and inflation of a cuff increase the likelihood of improper maintenance.

f. Steadily increasing cuff volume necessary to maintain a specific cuff pressure may indicate

A Complete suctioning of lower airway

B Complete suctioning of upper airway above the cuff

C Deflation of cuff while positive pressure is applied to direct any pooled secretions above the cuff up and out of the airway into the oropharynx

VIII Artificial Airway Emergencies

IX Management of Acute Obstruction of Artificial Airway

A Manipulate tube (check for kinks).

D If all of these fail and tension pneumothorax is ruled out, remove the tube and ventilate with bag and mask.

X Artificial Airway Suctioning (Modified from AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: Endotracheal Suctioning of Mechanically Ventilated Adults and Children with Artificial Airways, 1993)

1. The need to remove accumulated pulmonary secretions as evidenced by one of the following

a. Coarse breath sounds or “noisy” breathing

b. Patient’s inability to generate an effective spontaneous cough

c. Radiograph changes consistent with retained secretions

d. Changes in monitored flow/pressure graphics

e. Increased peak inspiratory pressure on volume control ventilation; decreased tidal volume on pressure control ventilation

f. Visible secretions in the airway

g. Suspected aspiration of gastric or upper airway secretions

h. Clinically apparent increased work of breathing

i. Deterioration of arterial blood gas values

j. The need to obtain a sputum specimen to rule out or identify pneumonia or other pulmonary infection or for sputum cytology

k. The need to maintain the patency and integrity of the artificial airway

l. The need to stimulate a cough in patients unable to cough effectively secondary to changes in mental status or the influence of medication

m. Presence of pulmonary atelectasis or consolidation, presumed to be associated with secretion retention

2. Tissue trauma to the tracheal and/or bronchial mucosa

7. Bronchoconstriction/bronchospasm

8. Infection (patient and/or caregiver)

9. Pulmonary hemorrhage/bleeding

10. Elevated intracranial pressure

D Ways to minimize risk of complications

1. Hyperoxygenation, when indicated, should minimize the risk of hypoxemia, arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest.

2. Use of appropriate suction pressure should minimize the risk of tracheal or bronchial trauma and pulmonary hemorrhage.

E Requisites of suction catheters

1. They should be constructed of a material that will cause minimal irritation and trauma to tracheal mucosa.

2. Minimal frictional resistance when passing through the artificial airway is essential.

3. They should be sufficiently long to easily pass the tip of the artificial airway.

4. They should have smooth, molded ends and side holes to prevent mucosal trauma.

5. The catheter outer diameter (OD) should be less than one half to two thirds the ID of the artificial airway.

a. Catheter size is the OD of the catheter in French (Fr) units, which refers to the circumference of the tube.

b. To convert French size to size in millimeters (approximation):

< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mml" />

c. To convert the size in millimeters to French size (approximation):

6. To minimize airway trauma use the following suction pressures.

F Suctioning of an artificial airway with open technique

1. Use completely sterile technique to prevent infection.

2. Assess Spo2 and vital signs of the patient for the need of hyperoxygenation.

3. Hyperoxygenate the patient, if indicated, by increasing the FIO2 delivered to the patient. Hyperinflation/hyperventilation with manual ventilator is usually not necessary and may be harmful to some patients.

4. Insert the catheter without applying suction until an obstruction is met, and then slightly retract the catheter.

5. Apply suction only during removal of the catheter.

6. The suction catheter should remain in the airway no longer than 10 to 15 seconds to minimize risk of hypoxemia and/or airway trauma.

7. Oxygenate and ventilate the patient as indicated.

8. In the event of catheter adherence to the wall of the airway, release suction, withdraw the catheter, and reapply suction.

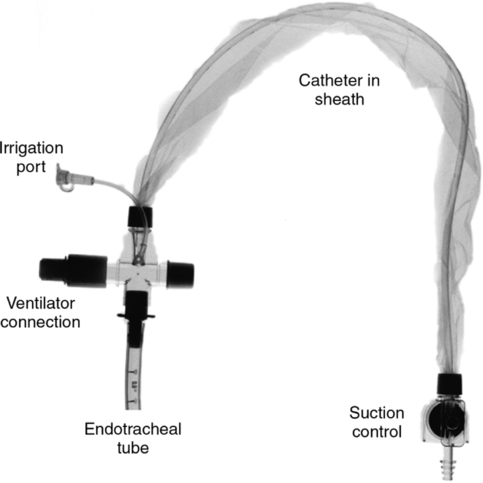

G Suctioning an artificial airway with closed suctioning system (Figure 38-10)

1. This system is permanently affixed to the airway-ventilator tubing system.

2. During suctioning mechanical ventilation is still maintained.

3. The suction catheter is located in the plastic sleeve and is advanced into the airway at the time of suctioning.

a. Disconnection from the ventilator, even for short periods, results in desaturation, bradycardia, and hypotension.

b. Patients require isolation because of highly communicable diseases.

5. This system generally reduces the risk of contamination of practitioners during suctioning.

6. The FIO2with these systems generally does not require adjustment during suctioning. However, each patient’s tolerance of the system should be evaluated with a pulse oximeter before the decision to maintain the FIO2 level during suctioning is made.

H Instillation of normal saline

1. The instillation of normal saline into the airway at the time of suctioning is normally unnecessary if

a. Proper systemic hydration is maintained.

b. Proper bronchial hygiene is provided.

c. Proper humidification of inspired gases is ensured.

d. However, if these criteria are not maintained, the instillation of 3 to 5 ml of sterile, normal saline solution before suctioning may help to mobilize thick, retained, difficult-to-suction secretions.