2 Agitation and Delirium

Agitation

Agitation

Agitation is a psychomotor disturbance characterized by a marked increase in motor and psychological activity.1 It is a state of extreme arousal, irritability, and motor restlessness that usually results from an internal sense of discomfort or tension and is characterized by repetitive, nonproductive movements that may appear purposeless, although careful observation of the patient sometimes reveals an underlying intent. In the ICU, agitation is frequently related to anxiety or delirium. Agitation may be caused by various factors: metabolic disorders (hypo- and hypernatremia), hyperthermia, hypoxia, hypotension, use of sedative drugs and/or analgesics, sepsis, alcohol withdrawal, and long-term psychoactive drug use to name a few.2,3 It can also be caused by external factors such as noise, discomfort, and pain.4 Associated with a longer length of stay in the ICU and higher costs,2 agitation can be mild, characterized by increased movements and an apparent inability to get comfortable, or it can be severe. Severe agitation can be life threatening, leading to higher rates of self-extubation, self-removal of catheters and medical devices, nosocomial infections,2 hypoxia, barotrauma, and/or hypotension due to patient/ventilator asynchrony. Indeed, recent studies have shown that agitation contributes to ventilator asynchrony, increased oxygen consumption, and increased production of CO2 and lactic acid; these effects can lead to life-threatening respiratory and metabolic acidosis.3

Delirium

Delirium

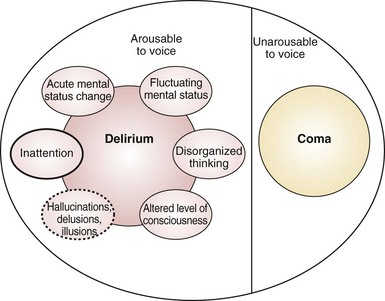

Delirium is an acute disturbance of consciousness accompanied by inattention, disorganized thinking, and perceptual disturbances that fluctuates over a short period of time (Figure 2-1).5 Delirium is commonly underdiagnosed in the ICU and has a reported prevalence of 20% to 80%, depending on the severity of illness and the need for mechanical ventilation.6–9 Recent investigations have shown that the presence of delirium is a strong predictor of longer hospital stay, higher costs, and increased risk of death.10–12 Each additional day with delirium increases the risk of dying by 10%.13 Longer periods of delirium are associated with greater degrees of cognitive decline when patients are evaluated after 1 year.12 Thus, delirium can adversely affect the quality of life in survivors of critical illnesses and may serve as an intermediary recognizable step for targeting therapies to prevent poor outcomes in survivors of critical illness.12,14

Unfortunately, the true prevalence and magnitude of delirium has been poorly documented because myriad terms—acute confusional state, ICU psychosis, acute brain dysfunction, encephalopathy—have been used to describe this condition.15 Delirium can be classified according to psychomotor behavior into hypoactive delirium or hyperactive delirium. Hypoactive delirium is characterized by decreased physical and mental activity and inattention. In contrast, hyperactive delirium is characterized by combativeness and agitation. Patients with both features have mixed delirium.16–18 Hyperactive delirium puts both patients and caregivers at risk for serious injuries, but fortunately this form of delirium occurs in a minority of critically ill patients.16–18 Hypoactive delirium actually may be associated with a worse prognosis.19,20

Although healthcare professionals realize the importance of recognizing delirium, it frequently goes unrecognized in the ICU.21–28 Even when ICU delirium is recognized, most clinicians consider it an expected event that is often iatrogenic and without consequence,21 though one needs to view this as a form of organic brain dysfunction that has consequences if left undiagnosed and untreated.

Risk Factors for Delirium

The risk factors for agitation and delirium are many and overlap to a large extent (Table 2-1). Fortunately there are several mnemonics that can aid clinicians in recalling the list; two common ones are IWATCHDEATH and DELIRIUM (Table 2-2). In practical terms, the risk factors can be divided into three categories: the acute illness itself, patient factors, and iatrogenic or environmental factors. Importantly, a number of medications that are commonly used in the ICU are associated with the development of agitation and delirium (Box 2-1). A thorough approach to the treatment and support of the acute illness (e.g., controlling sources of sepsis and giving appropriate antibiotics; correcting hypoxia, metabolic disturbances, dehydration, hyperthermia; normalizing sleep/wake cycle), as well as minimizing the iatrogenic factors (e.g., excessive sedation), can reduce the incidence or severity of delirium and its attendant complications.

| Age >70 years | BUN/creatinine ratio ≥18 |

| Transfer from a nursing home | Renal failure, creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL |

| History of depression | Liver disease |

| History of dementia, stroke, or epilepsy | CHF |

| Alcohol abuse within past month | Cardiogenic or septic shock |

| Tobacco use | Myocardial infarction |

| Drug overdose or illicit drug use | Infection |

| HIV infection | CNS pathology |

| Psychoactive medications | Urinary retention or fecal impaction |

| Hypo- or hypernatremia | Tube feeding |

| Hypo- or hyperglycemia | Rectal or bladder catheters |

| Hypo- or hyperthyroidism | Physical restraints |

| Hypothermia or fever | Central line catheters |

| Hypertension | Malnutrition or vitamin deficiencies |

| Hypoxia | Procedural complications |

| Acidosis or alkalosis | Visual or hearing impairment |

| Pain | Sleep disruption |

| Fear and anxiety |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CHF, congestive heart failure; CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

TABLE 2-2 Mnemonic for Risk Factors for Delirium and Agitation

| IWATCHDEATH | DELIRIUM |

|---|---|

| Infection | Drugs |

| Withdrawal | Electrolyte and physiologic abnormalities |

| Acute metabolic | Lack of drugs (withdrawal) |

| Trauma/pain | Infection |

| Central nervous system pathology | Reduced sensory input (blindness, deafness) |

| Hypoxia | Intracranial problems (CVA, meningitis, seizure) |

| Deficiencies (vitamin B12, thiamine) | Urinary retention and fecal impaction |

| Endocrinopathies (thyroid, adrenal) | Myocardial problems (MI, arrhythmia, CHF) |

| Acute vascular (hypertension, shock) | |

| Toxins/drugs | |

| Heavy metals |

CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; MI, myocardial infarction.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of delirium is poorly understood, although there are a number of hypotheses:

Assessment

Assessment

Recently the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) published guidelines for the use of sedatives and analgesics in the ICU.35 The SCCM recommended routine monitoring of pain, anxiety, and delirium and documentation of responses to therapy for these conditions.

There are many scales available for the assessment of agitation and sedation, including the Ramsay Scale,36 the Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS),37 the Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS),38 the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS),39 the Adaptation to Intensive Care Environment (ATICE)40 scale, and the Minnesota Sedation Assessment Tool (MSAT).40 Most of these scales have good reliability and validity among adult ICU patients and can be used to set targets for goal-directed sedative administration. The SAS, which scores agitation and sedation using a 7-point system, has excellent inter-rater reliability (kappa = 0.92), and it is highly correlated (r2 = 0.83 to 0.86) with other scales. The RASS (Table 2-3), however, is the only method shown to detect variations in the level of consciousness over time or in response to changes in sedative and analgesic drug use.41 The 10-point RASS scale has discrete criteria to distinguish levels of agitation and sedation. The evaluation of patients consists of a 3-step process. First, the patient is observed to determine whether he or she is alert, restless, or agitated (0 to +4). Second, if the patient is not alert and does not show positive motoric characteristics, the patient’s name is called and the sedation level is scored, depending on the duration of eye contact (−1 to −3). Third, if there is no eye opening with verbal stimulation, the shoulder is shaken or the sternum is rubbed, and the response is noted (−4 or −5). This assessment takes less than 20 seconds and correlates well with other measures of sedation (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS], bispectral electroencephalography, neuropsychiatric ratings).39

| +4 | Combative | Combative, violent, immediate danger to staff |

| +3 | Very agitated | Pulls or removes tube(s) or catheter(s); aggressive |

| +2 | Agitated | Frequent nonpurposeful movement; fights ventilator |

| +1 | Restless | Anxious, apprehensive, but movements not aggressive or vigorous |

| 0 | Alert and calm | |

| −1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert but has sustained (>10 sec) awakening (eye opening/contact) to voice |

| −2 | Light sedation | Drowsy; briefly (<10 sec) awakens to voice or physical stimulation |

| −3 | Moderate sedation | Movement or eye opening (but no eye contact) to voice |

| −4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice, but movement or eye opening to physical stimulation |

| −5 | Unarousable | No response to voice or physical stimulation |

| Procedure for Assessment | ||

| 1. Observe patient. Is patient alert, restless, or agitated? | (Score 0 to +4) | |

| 2. If not alert, state patient’s name and tell him or her to open eyes and look at speaker. Patient awakens, with sustained eye opening and eye contact. | (Score −1) | |

| Patient awakens, with eye opening and eye contact, but not sustained. | (Score −2) | |

| Patient does not awaken (no eye contact) but has eye opening or movement in response to voice. | (Score −3) | |

| 3. Physically stimulate patient by shaking shoulder and/or rubbing sternum. No response to voice, but response (movement) to physical stimulation. | (Score −4) | |

| 4. No response to voice or physical stimulation | (Score −5) | |

From Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166(10):1338-1344.

Until recently, there was no valid and reliable way to assess delirium in critically ill patients, many of whom are nonverbal owing to sedation or mechanical ventilation. However, a number of tools have been developed recently to aid in the detection of delirium in the ICU. These tools have been validated for use in both intubated and nonintubated patients and measured against a “gold standard,” the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria. The new tools are the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU),42–46 the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC),7 and the Neelon and Champagne (NEECHAM) Confusion Scale.47,48

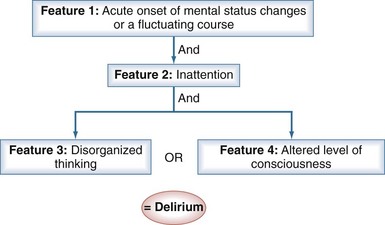

The CAM-ICU (Figure 2-2) is a delirium measurement tool that was developed by a team of specialists in critical care, psychiatry, neurology, and geriatrics.42,49 Administered by a nurse, the evaluation takes only 1 to 2 minutes to conduct and is 98% accurate for detecting delirium as compared with a full DSM-IV assessment by a geriatric psychiatrist.42,43 To perform the CAM-ICU, patients are first evaluated for level of consciousness; patients who respond to verbal commands (a RASS score of −3 or higher level of arousal) can then be assessed for delirium. The CAM-ICU comprises four features: (1) a change in mental status from baseline or a fluctuation in mental status, (2) inattention, (3) disorganized thinking, and (4) altered level of consciousness. Delirium is diagnosed if patients have features 1 and 2, and either 3 or 4 is positive (see Figure 2-2).

The ICDSC7 (Table 2-4) is a checklist-based assessment tool that evaluates inattention, disorientation, hallucination, delusion or psychosis, psychomotor agitation or retardation, inappropriate speech or mood, sleep/wake cycle disturbances, and fluctuation of these symptoms. Each of the eight items is scored as absent or present (0 or 1), respectively, and summed. A score of 4 or above indicates delirium, while 0 indicates no delirium. Patients with scores between 1 and 3 are considered to have subsyndromal delirium,50 which has worse prognostic implications than absence of delirium but a better prognosis than clearly present delirium.

TABLE 2-4 Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist

| Patient Evaluation | |

| Altered level of consciousness | (A–E)* |

| Inattention | Difficulty in following a conversation or instructions. Easily distracted by external stimuli. Difficulty in shifting focus. Any of these scores 1 point. |

| Disorientation | Any obvious mistake in time, place, or person scores 1 point. |

| Hallucinations-delusions-psychosis | The unequivocal clinical manifestation of hallucination or behavior probably attributable to hallucination or delusion. Gross impairment in reality testing. Any of these scores 1 point. |

| Psychomotor agitation or retardation | Hyperactivity requiring the use of additional sedative drugs or restraints to control potential danger to self or others. Hypoactivity or clinically noticeable psychomotor slowing. |

| Inappropriate speech or mood | Inappropriate, disorganized, or incoherent speech. Inappropriate display of emotion related to events or situation. Any of these scores 1 point. |

| Sleep/wake cycle disturbance | Sleeping less than 4 h or waking frequently at night (do not consider wakefulness initiated by medical staff or loud environment). Sleeping during most of the day. Any of these scores 1 point. |

| Symptom fluctuation | Fluctuation of the manifestation of any item or symptom over 24h scores 1 point. |

| Total Score (0-8) | |

The NEECHAM scale47,48 consists of nine items divided over three subscales. Each item consists of three to six descriptions. Subscale 1 (information processing) measures attention, processing of commands, and orientation; subscale 2 (behavior) measures appearance, motor behavior, and verbal behavior; subscale 3 (physiologic condition) measures vital function, oxygen saturation, and urinary continence. The overall score of the NEECHAM ranges from 0 to 30 points. The scale gives four grades of outcome: moderate to severe confusion and/or delirium (0-19 points), mild to early confusion and/or delirium (20-24 points), “not confused” but at high risk of confusion and/or delirium (25-26 points), and normal cognitive functioning—that is, absence of confusion and/or delirium (27-30 points). This instrument does not perform well in mechanically ventilated patients.

Management

Management

The development of effective evidence-based strategies and protocols for prevention and treatment of delirium awaits data from ongoing randomized clinical trials of both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic strategies. Refer to Chapter 205 for a detailed description of management strategies of delirium, including an empirical sedation and delirium protocol. A brief overview is provided here.

A “liberation” and “animation” strategy provides a good framework to reduce the incidence and duration of delirium.51 “Liberation” utilizes sedation protocols, linked spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, and proper sedation regimens to reduce the harmful effects of sedative exposure. Data from the Maximizing Efficacy of Targeted Sedation and Reducing Neurological Dysfunction (MENDS)52 study and the Safety and Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine Compared to Midazolam (SEDCOM) trial53 support the view that dexmedetomidine can decrease the duration and prevalence of delirium when compared to lorazepam or midazolam. “Animation” refers to early mobilization of ICU patients, which has been shown to reduce delirium and improve neurocognitive and functional outcomes.54

Pharmacologic therapy should be attempted only after correcting any contributing factors or underlying physiologic abnormalities. Although these agents are intended to improve cognition, they all have psychoactive effects that can further cloud the sensorium and promote a longer overall duration of cognitive impairment. Patients who manifest delirium should be treated with a traditional antipsychotic medication; the SCCM guidelines35 recommend haloperidol as the drug of choice. A recommended starting dose is 2 to 5 mg every 6 to 12 hours (IV or PO); the maximal effective doses are usually around 20 mg/day. Newer “atypical” antipsychotic agents (e.g., risperidone, ziprasidone, quetiapine, olanzapine) also may prove helpful for the treatment of delirium.55

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753-1762.

Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(5):859-864.

Pisani M, Kong S, Kasl S, Murphy T, Araujo K, Van Ness P. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1092-1097.

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703-2710.

Schweickert W, Pohlman M, Pohlman A, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874-1882.

1 Chevrolet J, Jolliet P. Clinical review: agitation and delirium in the critically ill–significance and management. Crit Care. 2007;11(3):214.

2 Jaber S, Chanques G, Altairac C, et al. A prospective study of agitation in a medical-surgical ICU: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Chest. 2005;128(4):2749.

3 Cohen I, Gallagher T, Pohlman A, Dasta J, Abraham E, Papadokos P. Management of the agitated intensive care unit patient. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):S97.

4 Pandharipande P, Jackson J, Ely EW. Delirium: acute cognitive dysfunction in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(4):360-368.

5 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6 Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753-1762.

7 Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(5):859-864.

8 McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):591-598.

9 Girard T, Pandharipande P, Ely E. Delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2008;12(Suppl. 3):S3.

10 Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(12):1892-1900.

11 Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):955-962.

12 Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. Jul 2010;38(7):1513-1520.

13 Pisani M, Kong S, Kasl S, Murphy T, Araujo K, Van Ness P. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1092-1097.

14 Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Hart RP, Hopkins RO, Ely EW. The association between delirium and cognitive decline: a review of the empirical literature. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14(2):87-98.

15 Morandi A, Pandharipande P, Trabucchi M, et al. Understanding international differences in terminology for delirium and other types of acute brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(10):1907-1915.

16 Peterson JF, Truman BL, Shintani A, Thomason JWW, Jackson JC, Ely EW. The prevalence of hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed type delirium in medical ICU patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:S174.

17 Peterson JF, Pun BT, Dittus RS, et al. Delirium and its motoric subtypes: a study of 614 critically ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):479-484.

18 Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Motoric subtypes of delirium in mechanically ventilated surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1726-1731.

19 Meagher D, O’Hanlon D, O’Mahony E, Casey P, Trzepacz P. Relationship between symptoms and motoric subtype of delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(1):51.

20 Kiely D, Jones R, Bergmann M, Marcantonio E. Association between psychomotor activity delirium subtypes and mortality among newly admitted postacute facility patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(2):174.

21 Ely EW, Stephens RK, Jackson JC, et al. Current opinions regarding the importance, diagnosis, and management of delirium in the intensive care unit: a survey of 912 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(1):106-112.

22 Cheung C, Alibhai S, Robinson M, et al. Recognition and labeling of delirium symptoms by intensivists: does it matter? Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(3):437-446.

23 Devlin J, Fong J, Howard E, et al. Assessment of delirium in the intensive care unit: nursing practices and perceptions. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(6):555.

24 Van Eijk M, Kesecioglu J, Slooter A. Intensive care delirium monitoring and standardised treatment: a complete survey of Dutch intensive care units. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2008;24(4):218-221.

25 Cadogan F, Riekerk B, Vreeswijk R, et al. Current awareness of delirium in the intensive care unit: a postal survey in the Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2009;67(7):296-300.

26 Patel R, Gambrell M, Speroff T, et al. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):825.

27 Salluh J, Dal-Pizzol F, Mello P, et al. Delirium recognition and sedation practices in critically ill patients: a survey on the attitudes of 1015 Brazilian critical care physicians. J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):556-562.

28 Mac Sweeney R, Barber V, Page V, et al. A national survey of the management of delirium in UK intensive care units. QJM. 2010;103(4):243-251.

29 Trzepacz PT. Update on the neuropathogenesis of delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:330-334.

30 Trzepacz PT. Delirium. Advances in diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(3):429-448.

31 Flacker JM, Lipsitz LA. Large neutral amino acid changes and delirium in febrile elderly medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(5):B249-B252.

32 Gunther M, Morandi A, Ely E. Pathophysiology of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(1):45-65.

33 Fink MP, Evans TW. Mechanisms of organ dysfunction in critical illness: report from a Round Table Conference held in Brussels. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(3):369-375.

34 Pandharipande P, Morandi A, Adams J, et al. Plasma tryptophan and tyrosine levels are independent risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(11):1886-1892.

35 Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):119-141.

36 Ramsay MA, Keenan SP. Measuring level of sedation in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2000;284:441-442.

37 Riker RR, Picard JT, Fraser GL. Prospective evaluation of the Sedation-Agitation Scale for adult critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1325-1329.

38 Devlin JW, Boleski G, Mlynarek M, et al. Motor Activity Assessment Scale: a valid and reliable sedation scale for use with mechanically ventilated patients in an adult surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1271-1275.

39 Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003;289(22):2983-2991.

40 Weinert C, McFarland L. The state of intubated ICU patients: development of a two-dimensional sedation rating scale for critically ill adults. Chest. 2004;126(6):1883-1890.

41 Sessler C, Grap M, Ramsay M. Evaluating and monitoring analgesia and sedation in the intensive care unit. Critical Care. 2008;12(Suppl. 3):S2.

42 Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370-1379.

43 Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703-2710.

44 Lin SM, Liu CY, Wang CH, et al. The impact of delirium on the survival of mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2254-2259.

45 Larsson C, Axell AG, Ersson A. Confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU): translation, retranslation and validation into Swedish intensive care settings. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(7):888-892.

46 McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Ely EW, Gifford D, Inouye SK. Detection of delirium in the intensive care unit: comparison of confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit with confusion assessment method ratings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):495-500.

47 Csokasy J. Assessment of acute confusion: use of the NEECHAM Confusion Scale. Appl Nurs Res. 1999;12(1):51-55.

48 Immers H, Schuurmans M, van de Bijl J. Recognition of delirium in ICU patients: a diagnostic study of the NEECHAM confusion scale in ICU patients. BMC Nurs. 2005;4(1):7.

49 Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

50 Ouimet S, Riker R, Bergeon N, Cossette M, Kavanagh B, Skrobik Y. Subsyndromal delirium in the ICU: evidence for a disease spectrum. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(6):1007-1013.

51 King M, Render M, Ely E, Watson P. Liberation and animation: strategies to minimize brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:87-96.

52 Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, et al. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644-2653.

53 Riker R, Shehabi Y, Bokesch P, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(5):489.

54 Schweickert W, Pohlman M, Pohlman A, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874-1882.

55 Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Gottfried SB. Olanzapine vs haloperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.