Chapter 32 Ageing and cognition

OVERVIEW AND AETIOLOGY

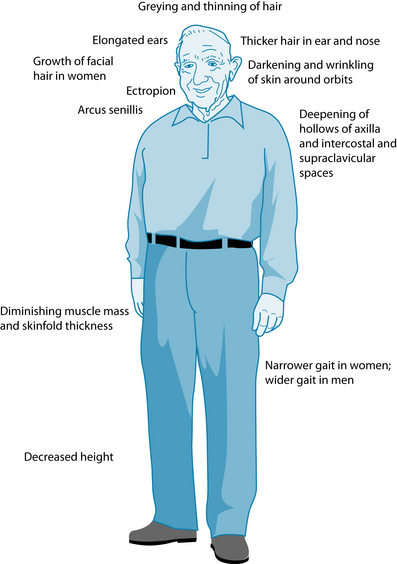

Ageing is a multidimensional process comprising physical, psychological and social factors that vary and interact over the life span.1,2 Normal ageing is characterised by organ and system changes that vary among individuals depending on the physical, emotional, psychological and social changes experienced during life.3 These changes are influenced by such factors as genetics, physical and social environments, diet, health, stress and lifestyle choices. In the absence of disease the normal ageing process involves changes and impairment in systems of the body leading to structural and functional changes, some of which can be noticeable upon inspection of the older patient (refer to Figure 32.1). The focus of this chapter regards ageing in the latter stages of life, specifically in elderly people (65+ years). In the recent decades, individuals of this group in developed countries have experienced a dramatic increase in life expectancy, and a declining death rate, which has given rise to a vastly older population.

Over the past 20 years in Australia, life expectancy has improved by 6 years for males and 4.1 years for females; males and females born between 2005 and 2007 in Australia are expected to live 79 and 83.7 years, respectively.4 In the year 2000, 10% of the global population was aged 60 years or older and this percentage is projected to reach 21% by 2050.5 In 2007 13% of Australians were reported to be over the age of 65 years.4 An increasingly older population leads to an increase in the number of individuals suffering from debilitating age-related diseases, including dementia, cardiovascular disease and cancer. In 2005, the global population suffering dementia was estimated at 24.3 million people, and there are around 4.6 million new cases diagnosed every year.7 Furthermore, it is predicted that this population will double every 20 years with an alarming number of 81.1 million dementia patients in 2040.

A chief consequence of an ageing population is an increased burden on public health systems, as the elderly have higher rates of hospitalisation, surgery and visits to their physician than any other age group;3 this has led to spiralling health-care costs. For example, health-care costs in the United States of America totalled around $3.6 billion in 1992, $12.7 billion in 1995, $1.4 trillion in 2001 and $1.9 trillion in 2004.8 It is anticipated that these figures will increase to $2.8 trillion by 2011.9 The holistic and preventive approach that is inherent in naturopathic practices suggest a clear role for these disciplines in the promotion of healthy ageing, and assisting in meeting the population and individual health challenges of the future. A comprehensive naturopathic system review will provide a detailed account of systems that are most affected during the ageing process for each individual. Furthermore, given that the pattern of ageing is unique to each individual,3 naturopathic treatment needs to be tailored according to individual health and wellbeing needs.

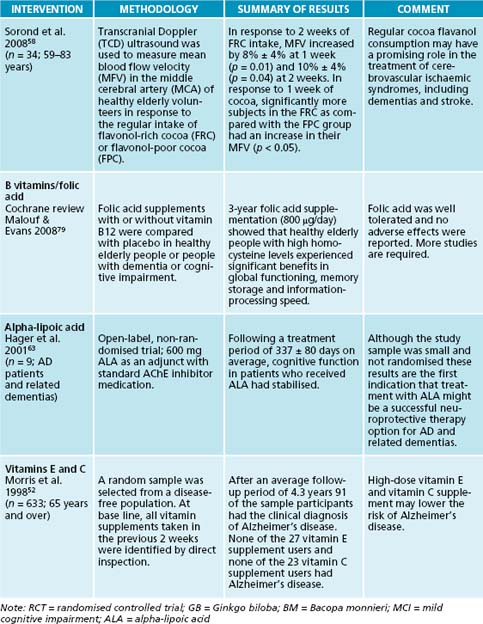

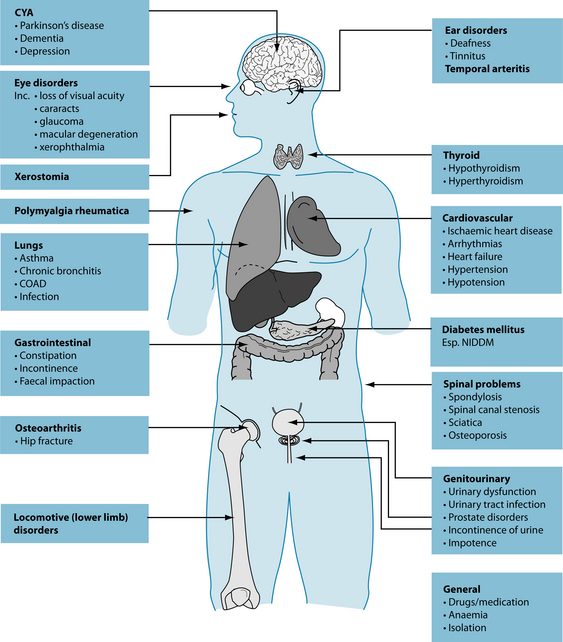

Figure 32.2 indicates common diseases and illnesses seen in the elderly patient, such as cardiovascular disease, arthritis, diabetes, infections, cancer and gastrointestinal disturbances. (Refer to the respective chapters in this book for details on how to address these conditions holistically.)

Figure 32.2 Common conditions seen in the elderly

Source: Murtagh J. General practice. 4th edn. Sydney: McGraw-Hill Australia, 2006.

Due to a number of changes in body composition, gastrointestinal function and sensory function, older people are prone to dysfunction in the digestive system and as a result are at risk of malnutrition.10 In particular a poor production of digestive enzymes may lead to inadequate digestion and assimilation of micronutrients to vital tissues and organs of the body, resulting in adverse consequences such as poor health, poor immunity and disability.10 It is therefore vital to improve digestive functions and address resulting nutritional deficiencies (refer to the section on the digestive system). Other conditions commonly seen in the older population include osteoporosis, incontinence, visual and hearing difficulties, sleep disorders and depression (refer to Table 32.1).

Table 32.1 Common conditions seen in the elderly and naturopathic treatment approach, except cardio/cerebrovascular disease and cancer (see Section 3 on the cardiovascular system and Chapter 29 on cancer).

| CONDITIONS COMMONLY SEEN IN THE ELDERLY | NATUROPATHIC TREATMENT APPROACH |

|---|---|

| Osteoporosis | Calcium and vitamin D are important for improving bone mass and preventing bone fractures and falls. RDAs For people aged 65+ years are:11

Increase dairy products (milk, yoghurts and cheese) and fish (sardines with bones). |

Less salient ailments in the elderly population

While some conditions, such as those of the cardiovascular and neural systems, are commonly linked to the elderly other less salient conditions often mitigated by life changes can also affect their quality of life. Examples are leaving the workforce and entering the retirement years, widowhood and grandparenting, but other more gradual changes, such as becoming more dependent on family and social services in addition to requiring more acute care, have a substantial influence on the lives of the elderly. A recent review showed that loneliness is widespread amongst the elderly, and is linked to depression, high blood pressure, poor sleep, immune stress response and a decline in cognition.16 Although sleep disturbances are not part of the normal ageing process, sleep becomes lighter with age and insomnia is prevalent in the older population with more than 49% of those aged 65 years and over experiencing sleep disturbances.17 Inadequate sleep results in increased risk of falls, difficulties with concentration, impairments in memory and decrease in quality of life.18 A large study (n = 1506) revealed that depression, heart disease, body pain and memory problems were associated with symptoms of insomnia in older adults, suggesting that sleep complaints are secondary to comorbidities in this population rather than due to ageing as such.19 As a practitioner, it is therefore important to identify and understand the causes of sleep difficulties in the older patient (refer to Chapter 14 on insomnia).

Therapeutic considerations in the elderly

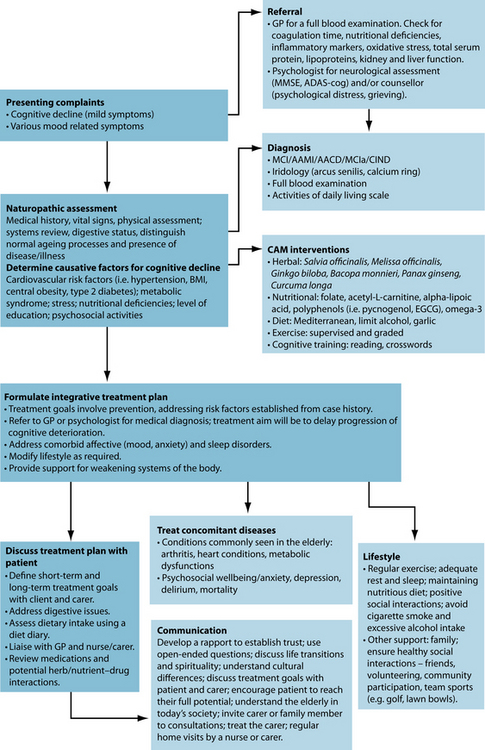

Age-related chronic diseases are often not successfully treated by conventional methods since these therapies often fail to provide long-term relief and have adverse side effects. Although the popularity of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the older population is unclear, the elderly (65 years or older) appear more likely than younger adults to discuss their CAM treatments with their doctors; clinical nutrition, chiropractic, massage therapy, meditation and herbal medicine were the most common forms of CAM used by the elderly.6 Diagnosis of cognitive impairment in most countries must be made by a medical physician and be subsequently carefully monitored, and doctors need to be more active in initiating conversation about CAM use with their patients.

A medical history will help determine the timing of the disease onset, and assessment using the Minimental scales and measures of depression such as the geriatric depression scale20 are valuable. Additionally, full blood cell count tests for thyroid, kidney and liver function, and serum level of vitamin B12 are recommended. A naturopathic treatment approach needs to consider the stage at which the elderly individual is, mentally and physically, in their ageing process. Each individual has been exposed to different factors in their lifetime that may either protect or increase the risk of developing cognitive decline and associated diseases. A detailed account of the presenting case and patient history will help determine an appropriate naturopathic treatment approach. The patient history will need to determine the likely risk factors that may have contributed to presenting cognitive complaints, and determine whether or not the presenting symptoms are due to normal or pathological ageing.

Wear and tear on the body over the years affects not only the brain and vascular system, but also other body parts. This may lead to knee replacements due to lack of cartilage, painful arthritic joints, loss of bone mass in the hips and lack of balance, leading to falls—and leading to reduced capacities overall.21 Although not all elderly individuals are frail some operate slowly, walk slowly, experience difficulties hearing and may need time to stop and rest. It is therefore essential to consider these expected changes in the elderly person during the naturopathic consultations, and treat other chronic illnesses such as arthritis, diabetes or heart disease. It is also essential to support changes to systems of the body naturally seen in the elderly, such as improving gastrointestinal function (with bitters, protease/amylases/lipase and gut bacteria), supporting the cardiovascular system (with circulatory stimulants and cardiac tonics), regulating cholesterol levels, treating infections (with immune system stimulants), encouraging exercise to improve bone mass and muscle tone, supporting the genitourinary system (with urinary tonics) and seeking regular hearing and vision tests.

When the elderly suffer from various diseases and infections they are prone to using polypharmacy, so possible interactions with vitamins and herbs need to be well thought out prior to prescribing a naturopathic treatment regimen. Possible interactions with commonly used herbs, drugs and nutrients are outlined in drug–CAM interaction table in Appendix 1.

Normal brain ageing

structure that allows the older adult to maintain social connectedness, an ongoing sense of purpose, and the abilities to function independently, to permit functional recovery from illness or injury, and to cope with residual functional deficits’.22

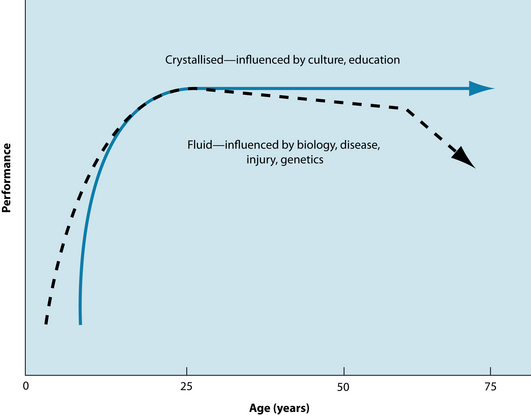

Cognitive functions such as learning, memory and attention can be affected by ageing, with some aspects of cognition being preserved while others decline.23 Cognitive abilities can be classified as ‘fluid’ when they rely on short-term memory storage to process information, or ‘crystallised’ where knowledge and expertise accumulates and relies on long-term memory.24 Fluid intelligence involves solving new problems, spatial manipulation, mental speed and identifying complex relations among stimulus patterns. Such fluid abilities are believed to peak in the mid 20s and then gradually decline until the age of 60 years, when the decline becomes more rapid.24 In contrast, crystallised abilities increase during the life span through education, occupational and cultural experiences. Intellectual pursuits are thought to slow in late adulthood and may gradually decline from the age of 90 years (refer to Figure 32.3); they are affected by ageing and disease and often remain intact even in the early stages of dementia or after brain injury.24

Ageing significantly affects long-term memory for specific events (episodic memory), whereas some other aspects of long-term memory, such as procedural memory, are well maintained.23 It is important for the naturopathic practitioner to detect signs of early cognitive decline in older patients and, using a combination of herbal, nutritional and lifestyle interventions together with appropriate referrals to other medical practitioners, prepare older patients for making decisions about their future care before they have lost the ability to do so.25

Pathological cognitive decline

Individuals who experience cognitive decline are at a greater risk of developing dementia, and researchers suggest that early detection and intervention may be effective strategies to slow the progress of dementia.22 Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) is the most common of the subtypes of the dementias26 characterised by the presence of amyloid-beta-protein (AβP) and intraneural deposition of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain; although this pathology is also seen in non-demented individuals, it is the distribution of these plaques in the brain that differentiates normal and abnormal brain changes.27 Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a condition presenting with memory deficits that are below the defined norms and in the absence of other cognitive dysfunctions, and although it is thought to be a preclinical state of dementia28 approximately half of MCI individuals go on to develop AD.29 This again furnishes a role for naturopaths to work in conjunction with other medical professionals qualified to diagnose and monitor the progression of cognitive decline and provide a complementary treatment approach to prescribing holistic remedies proven to slow the progression of cognitive decline in these individuals.

Cerebrovascular conditions

Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is defined as brain lesions caused by vascular disorders including cerebral infarction or acute cessation of blood flow to a localised area of the brain; brain haemorrhage caused by rupture in a vascular wall; and vascular dementia, caused by multiple small infarcts and subcortical Binswanger-like white-matter.27 Vascular dementia (VaD) is recognised as the second most prevalent type of dementia. There is a large body of evidence linking cerebrovascular benefits with treatment of broader cardiovascular risk factors.30 Older patients presenting with the problems of cognitive decline and depression should therefore have vascular risk assessed and treated more broadly.

Screening tools

When appropriate, naturopaths treating older patients are encouraged to arrange referrals to health professionals qualified to detect normal from abnormal brain ageing. Although there is no universally accepted measure to detect preclinical signs of AD, psychologists, psychiatrists and neuropsychologists are qualified to administer screening tools, which, by measuring patients’ subjective or objective cognitive decline, can help distinguish normal from abnormal brain ageing, and the progression or stabilisation of cognitive decline.25 Such screening tools include the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (refer to Table 32.2).

| SCREENING TOOL | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| MMSE | A 30-point test that is commonly used to screen for dementia. The MMSE evaluates six areas of cognitive function: orientation, attention, immediate recall, short-term recall, language, and the ability to follow simple verbal and written commands. Scores: 20–26 = some cognitive impairment |

RISK FACTORS

Several risk factors have been associated with the development of cognitive decline (for example, VaD and AD) including:26,35–38

Elevated blood pressure, for example, has been found to influence cognitive ability: hypertension increases the risk of vascular and endothelial damage and disrupts the blood–brain barrier,26 and it has been proposed that a reduction in high blood pressure may be a preventive measure against stroke and cognitive decline in elderly patients.39 Furthermore, increased central adipose tissue has been linked to vascular and metabolic factors that give rise to cognitive decline and dementia and there is emerging evidence suggesting that metabolic syndrome is associated with an increased risk of dementia. A greater waist to hip ratio (WHR) and age are significantly negatively correlated to hippocampal volumes, suggesting that a larger WHR may be related to neurodegenerative, vascular or metabolic processes that affect brain structures underlying cognitive decline and dementia.36 Studies assessing the link between hypercholesterolaemia, atrial fibrillation, smoking and dementia have given more conflicting results.40 Clinicians need to consider lifestyle interventions towards an early and effective cardiovascular risk-factor management to reduce the risk of cardiometabolic and the cognitive decline.41

A history of nervous disorders such as anxiety and depression has also been linked to poor cognitive health later on in life.22 In particular, anxiety is a common feature of dementia, occurring in higher levels in VaD compared to AD, while people in severe stages of dementia tend to experience decreased levels of anxiety.42 Furthermore, anxiety in dementia patients has been associated with poor quality of life and behavioural disturbances, even after controlling for depression.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Currently pharmacological treatments are available for the short-term symptoms of dementia through the use of cholinesterase inhibitors, rather than modifying the disease as such.43 The central cholinergic system has a pertinent role in regulating cognitive functioning and a consistent deficit in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in the hippocampal area of the brain is a key feature of AD.44 Inhibition of acetyl-cholinesterase (AChE), the main enzyme involved in the breakdown of ACh, is the key strategy for the short-term relief of symptoms commonly seen in AD. These therapies include the medications Donepezil, Tacrine and galantamine, in addition to drugs such as rivastigmine and, although these treatments delay the symptomatic progression associated with AD by 6 to 12 months,43 they can cause adverse effects including gastrointestinal disturbances, diarrhoea, muscle cramps, fatigue, nausea, rhinitis, vomiting, anorexia and insomnia.45 Additionally, ACh inhibitors such as galantamine, huperzine A, physostigmine and its derivatives have been used to increase the levels of ACh to improve neural functioning.46

Since there is no cure for AD, preventive measures are very important and are commonly prescribed by medical practitioners. To this end, some conventional medications, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic and hypertension medications are thought to be effective in preventing the onset of dementia. The therapeutic action of these medications targets the brain systems that scientists think are impaired in dementia and other age-related diseases including CVD.47

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

The causes of age-related cognitive decline and pathologies such as AD are not known. The underlying mechanisms associated with normal ageing need to be understood in order to understand abnormal ageing present in cognitive decline, and it is thought that cognitive decline may be a multifactorial process involving dietary, environmental, genetic and physiological mechanisms.48

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is strongly implicated in the ageing process in addition to various disease states, including cardiovascular conditions such as stroke, CVD and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and dementia.49,50 This process is most commonly explained by the ‘free radical theory’ of ageing, which was first proposed by Harman in the 1950s and holds that highly reactive chemicals in the body (free radicals) damage cells via chemical processes that accumulate over time and result in severe cell damage and cell death.50 During normal metabolic processes highly reactive (free radical) species of oxygen (reactive oxygen species, ROS), nitrogen (reactive nitrogen species, RNS) and chorine (reactive chlorine species, RCS) are produced. Normally these reactive species (or oxidants) play important roles in the immune system, helping kill microorganisms and fight off diseases, but in excessive amounts free radicals initiate chemical reactions that damage proteins, carbohydrates, membrane lipids and DNA.49,50 An inbuilt oxidative defence mechanism ordinarily protects the body against these oxidative reactions by counteracting the effects of these reactive molecules and preventing cellular destruction. However, when the body is unable to counteract the effects of these reactive substances they are left to destroy cellular processes disturbing physiological functions. Antioxidant micronutrients such as vitamin C, vitamin E and carotenoids are important in combating the effects of oxidative stress; inadequate dietary intake of these is thought to increase the risk of degenerative diseases including AD and MCI.50 Rectifying deficiencies in these nutrients may be one aim of combating oxidative stress in the ageing individual.

components for AD. Vegetables, particularly those high in vitamins C and E, which have antioxidant properties, have also been linked to lowering the risk of AD.51 High-dose vitamin E and vitamin C supplementation may lower the risk of AD. One study52 examined the association between the use of vitamin E and vitamin C and the incidence of AD. A large sample of 633 participants aged 65 years and older were followed up an average of 4.3 years, and it was found that 91 of the participants with vitamin information met accepted criteria for the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. None of the 27 vitamin E supplement users and none of the 23 vitamin C supplement users had AD. The authors concluded that the use of a high-dose vitamin E and vitamin C supplement may lower the risk of AD. Those with higher intakes of vitamin E from food sources may also reduce their risk of developing AD. Furthermore, a longitudinal population-based study (n = 2889; 65–102 years) found a 36% reduction in the rate of cognitive decline among high vitamin E consumers (from supplements and foods median dose = 387.4 IU/day) compared with low vitamin E consumers (median dose = 6.8 IU/day intake from foods (as measured by a food frequency questionnaire).

Elevated levels of F2-isoprostanes (metabolites indicative of free-radical oxidative damage) have been found to be present in patients with AD53 and the finding that pine bark extract has significant beneficial effects on cognitive functioning and F2-isoprostanes following 90 days’ administration (60–85 years; PYC 150 mg/day54) suggests the potential benefit of this treatment in improving cognition in the elderly.

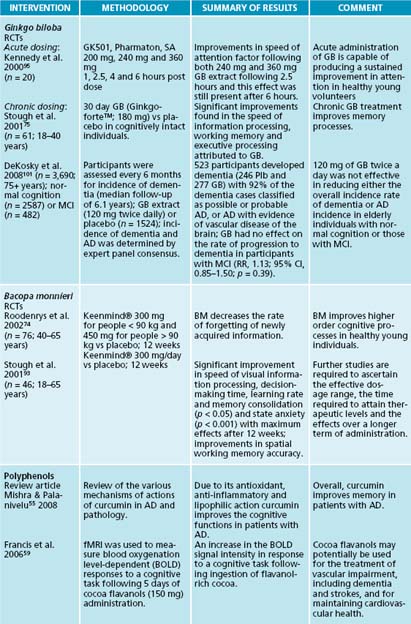

Polyphenols are antioxidants found in fruits and vegetables and have been shown to have cognitive effects. The polyphenol curcumin has been shown to improve cognitive functioning in AD patients, and researchers suggest that this action is possibly due to curcumin’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and lipophilic actions; and since curcumin is lipophilic nature it may possibly cross the blood–brain barrier and bind to amyloid plaques.55 Additionally, preliminary human and animal studies show promising effects of polyphenols found naturally in cocoa as a treatment to delay age-related cognitive decline.56–59 These studies suggest that flavonol-containing foods may be an effective part of treatment for delaying age-related cognitive deficits in normal ageing and for cerebrovascular ischaemia syndromes including dementias and stroke by improving vascular health.

Free radical mitochondrial theory

Mitochondrial dysfunction may play a key role underlying pathological changes associated with ageing, including brain ageing, and may be associated with the onset and development of neurodegenerative diseases.48,60 Mitochondrial dysfunction can be caused by the oxidation of lipids, proteins and nucleic acid. The free radical mitochondrial theory of ageing asserts that cumulative oxidative injuries to the mitochondria cause the mitochondria to progressively become less efficient. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is involved in mitochondrial functions including the manufacturing of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and has been linked with improving cognitive functions. CoQ10 has been shown to have a neuroprotective effect in cognitive impairment and oxidative damage in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex in animals.61 Investigation of an integrative treatment approach on cognitive performance using antidepressants, cholinesterase inhibitors, and vitamins and supplements (multivitamins, vitamin E, alpha-lipoic acid, omega-3 and CoQ10) was found to delay cognitive decline for 24 months and also improve cognition, especially frontal lobe activity and memory in patients with mild dementia and depression.62

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) is a coenzyme involved in mitochondrial metabolism and is found in various food sources including meat and, at lower levels, in spinach, brewer’s yeast and wheat germ. ALA and its derivatives improve the age-associated decline of memory, improve mitochondrial structure and function, inhibit the age-associated increase of oxidative damage, elevate the levels of antioxidants, and restore the activity of key enzymes.48,60 Dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA)—a reduced form of ALA—is a strong antioxidant and has a key role in recycling other antioxidants including vitamins C and E, CoQ10 and glutathione. Additionally, DHLA chelates iron and copper.60 Animal studies have found ALA to be beneficial for delaying the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD; it improves age-associated cognitive dysfunction and neurodegenerative disease,60 though human trials remain in their infancy.63 Co-administration of ALA with other mitochondrial nutrients, such as acetyl-L-carnitine and coenzyme Q10, appears more effective in improving cognitive dysfunction and reducing oxidative mitochondrial dysfunction.48,60

Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALC) is derived from carnitine and has been reported to be an effective therapy for patients with Alzheimer’s disease.64 ALC acts on cholinergic neurons, enhances mitochondrial function and is involved with membrane stabilisation. Supplementation with ALC (2 g/day) in older individuals (> 65 years) with mild mental impairment has been associated with improved measures on behavioural scales, memory tests, attention barrage test and verbal fluency tests.64 Additionally, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial65 was carried out to compare 6 months of treatment with 1 g ALC twice daily and placebo in patients (n = 36) with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Although no significant findings were observed, trends were apparent in the ALC group, who showed improvements in short-term memory. Findings suggest the importance of ALC in the treatment of elderly patients with mental impairment and clinical features of AD, particularly those related to short-term memory; however, these conclusions are based on small samples and larger studies are required to confirm these findings. Despite positive findings of these earlier studies, authors of a Cochrane review suggest that at present there is no evidence to recommend the routine use of ALC in clinical practice.66

Inflammatory markers

A number of molecules associated with inflammation are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of AD. These include increases in inflammatory markers alpha 1-antichymotrypsin (ACT), interleukin-6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and oxidised low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in patients with AD.67 It has also been established that centenarians have a higher frequency of genetic markers associated with better control of inflammation; such control appears to exert a protective effect against the development of age-related pathologies that have a strong inflammatory pathogenetic component.67

Bacopa monnieri is an Ayurvedic herb used traditionally for memory decline. B. monnieri contains bacosides A and B (steroidal saponins) believed to be essential for the clinical efficacy of the product. Although the exact mechanism of action of B. monnieri on cognitive processes has not yet been established, evidence suggests that it may modulate the cholinergic system and/or have antioxidant effects possibly via metal chelation,68 remove β-amyloid deposits,69 act as an anti-inflammatory,70 anxiolytic71 and antidepressant72 and have adaptogenic properties.73 Chronic administration of B. monnieri has been shown to increase the levels of endogenous antioxidants in the prefrontal cortex, striatum and hippocampus via a mechanism that resembles that of the antioxidant vitamin E.68 B. monnieri supplementation has reduced specific amyloid peptides by as much as 60% while also improving a number of behavioural measures in an animal setting.69

Studies examining the effects of B. monnieri in healthy young adults have found significant improvements in the retention of new information, speed of visual information processing, speed of decision-making time, learning rate and memory consolidation, and improved performance on spatial working memory accuracy.74,75,68 Measures of speed are one of the most prominent deficits to be shown in studies examining cognitive deterioration in the elderly. In conclusion, these findings suggest that Bacopa monnieri improves higher order cognitive processes such as learning and memory in healthy young individuals. Additionally, studies examining the effects of B. monnieri in older adults revealed that B. monnieri improves retention of new information and decreases the rate of forgetting of newly acquired information (40–65 years; 150 mg × 2/daily).74 In addition, B. monnieri has been shown to improve depression and trait anxiety, and decrease heart rate in healthy elderly participants (65+ years) without clinical signs of dementia (300 g/day for 12 weeks).76

Vascular system and cognitive ageing

There is increasing evidence linking the role of vascular function to cognitive decline and dementia, so interventions that address these vascular factors may be effective in preventing cognitive impairments as seen in these individuals.77 A review of the literature outlined the following vascular factors as possible causes involved in brain ageing and cognitive decline: a reduced cerebral blood flow, reduced cerebral blood volume, poor capillary elasticity and poor vasodilatory capacity.48 Furthermore, cerebral blood flow (CBF) and volume (circulation) can be compromised by a number of factors, including age-reduced capillary elasticity and vasodilatory capacity, cholinergic deficits, vascular lesions and plaques, oxidative stress and glucose supply to the brain, which may affect the uptake and use of glucose and oxygen in the brain.48 Furthermore, a relationship exists between arterial stiffness and cognitive impairment, suggesting that functional changes of the arterial system could be involved in the onset of dementia (VaD or AD types).78 It is therefore reasonable to suggest that a strategy to prevent cognitive decline in the ageing individual may be to address the multiple mechanisms associated with brain ageing with appropriate supportive interventions, before normal age-related cognitive decline accelerates, potentially leading to impairments and eventual dementia.48

Elevated levels of the amino acid homocysteine are also associated with cognitive dysfunction in the elderly. Folate deficiency is associated with high blood levels of homocysteine, linked to the risk of arterial disease, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.79 There is no current evidence showing benefits following folic acid supplementation with vitamin B12 on cognitive function and mood in healthy elderly people.79 However, in another trial supplementation 800 μg/day folic acid over 3 years was associated with significant improvements in global functioning, memory storage and information-processing speed in healthy elderly individuals with high homocysteine levels. Folic acid supplementation has also been shown to significantly improve overall response to cholinesterase inhibitors and scores on the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and the Social Behaviour subscale of the Nurse’s Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients in patients with AD.79 However, supplementation with vitamin B12 did not show benefit in measures of cognitive function in participants with cognitive impairment.

Older subjects with greater intakes of fruits and vegetables, and the corresponding nutrients vitamin C and folate, have been shown to perform better on cognitive tests.80.

Heavy metals

Levels of zinc, copper and iron are significantly altered in AD brain tissue, particularly in subcortical regions such as the hippocampus, amygdala and neocortex.81 Recent findings suggest that metal complexing agents may have therapeutic benefits in AD.82 Curcumin’s anti-inflammatory actions are believed to be due in part to its metal-chelating effects; it also has the ability to bind to heavy metals—particularly copper and iron—and as a result prevent neurotoxicity caused by such metals.83 As already mentioned B. monnieri is believed to not only modulate the cholinergic system and/or have antioxidant effects, and remove β-amyloid deposits, but it also acts as a metal chelator.

Genetics

It has been suggested that genetic susceptibility is implicated in the cognitive impairment seen in ageing. For example, apolipoprotein E (Apo E) and ACE genes have been associated with cognitive impairments seen in ageing and dementia. Individuals carrying the Apo E epsilon4 allele exhibit lower memory performance on tests related to declarative (storing facts) and procedural (long-term) memory.84 Furthermore, AD is an autosomal dominant disease involving four specific genes located on chromosomes 1, 14, 19 and 21; these genes have been associated with the progression of AD. Further research, however, is required to understand the relationship between Apo E and cognition.

Herbal cognitive enhancers

Chronic administration of Panax ginseng extracts has shown improvements in cognitive functioning and performance in healthy young and older individuals. Compared to a placebo group, 8–9 weeks’ administration of a standardised P. ginseng extract (400 mg/day) in healthy older participants (> 40 years) resulted in significant improvements in performance on cognitive tasks, specifically related to executive processing.85 Furthermore, 12 weeks of P. ginseng administration (G115) has been found to improve wellbeing.86 Cognitive function has also been studied in acute administration of various ginseng doses. A study87 examined the effects of 200, 400 and 600 mg P. ginseng (G115) following 1, 2.5, 4 and 6 hours post dose. These researchers found improvements in secondary memory factor for each dose, with more pronounced improvements seen with the 400 mg dose. Slowed performance was seen with the 200 and 600 mg doses, and the 200 and 400 mg doses were associated with declines in subjective alertness that reached significance by 6 hours post dose (the last testing session of the day). Additionally, various doses of P. ginseng (G115) and G. biloba extract (GK 501) combinations (320 mg, 640 mg and 960 mg) resulted in significant improvements in memory performance for the optimum dose of the combination (960 mg of the combined treatment) with this effect isolated to secondary memory, whereas lower doses (320 mg and 640 mg) resulted in deficiencies in speed on the attention tasks.88

G. biloba is one of the most widely researched herbs for the treatment and prevention of cognitive decline. The mechanisms by which G. biloba improves cognition are thought to be via platelet activating factor (PAF) antagonist activity,89 free radical scavenger activity,90,91,92 enhancing active choline uptake and improving cerebral blood flow. Although only a few trials have examined the effects of G. biloba in healthy cognitively intact older individuals, G. biloba has been shown to be effective in improving memory and cognitive function in healthy adults.93,94,95 However, some trials have not replicated positive results.94,96

G. biloba has also been widely examined in elderly patients with and without dementia. A study97 found that 6 weeks’ daily administration of EGb 761 (180 mg) was effective in enhancing certain neuropsychological and memory processes in cognitively intact older individuals (n = 262; > 60 years). Furthermore, two large, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trials96,99 examined the effects of G. biloba EGb 761 on patients with mild to severe dementia of the Alzheimer’s and vascular types. They found that treatment with 120 mg EGb 761 daily showed a statistically significant worsening in all domains of assessment and G. biloba was equivalent to stemming the course of the illness for 6 months.96,99 A study100 compared the effects of of G. biloba (EGb 761; 120 mg and 240 mg) administration to that of four cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, tacrine, rivastigmine and Metrifonate) in AD, and found that in all groups symptoms of dementia were delayed for similar periods of time and similar response rates were obtained. These findings suggest that both cholinesterase inhibitors and G. biloba (EGb 761) should be considered as equally effective in the treatment of mild to moderate AD.

Despite these positive findings, the results of the largest double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial conducted on the cognitive effects of G. biloba present conflicting outcomes. Another study101 investigated the effects of G. biloba (120 g b.d.; n = 1545) versus placebo (n = 1545) on reducing the incidence of dementia and AD in elderly individuals with normal cognition (n = 2587) and those with MCI (n = 482). In this multicentre trial, participants were assessed every 6 months for incident dementia for a mean number of 6.1 years. G. biloba was found to have no effect on the rate of progression to dementia in participants with normal cognition or those with MCI. Moreover, a G. biloba and B. monnieri administration over 4 weeks failed to find effects on cognitive function in healthy adults (18–68 years); however, it is possible that the dose was not sufficient or treatment duration was not long enough to produce a pharmacological effect.102 Furthermore, the authors of a recent review of the literature regarding the therapeutic effects of G. biloba in patients diagnosed with cognitive impairment and dementia concluded that the pattern of results from clinical trials is consistent.103 Although, compared to placebo, G. biloba appears to be safe and without adverse effects, the evidence indicating that G. biloba has a significant effect on patients with dementia or cognitive impairment is not convincing and further conventionally designed trials are unlikely to be useful.103 Hence, further trials are necessary before any firm conclusions can be drawn on the utility of G. biloba in these groups.

Salvia officinalis contains antioxidant, oestrogenic and anti-inflammatory properties, inhibits butyryl and acetyl-cholinesterase and has been found to improve mnemonic performance in healthy young and elderly participants.104 Furthermore, a 16-week administration of S. officinalis significantly improved scores on the ADAS-cog in patients with mild to moderate dementia.105 Melissa officinalis has been shown to have cholinergic binding properties in vitro and may ameliorate cognitive decline associated with AD. A randomised, placebo-controlled, double blind, balanced crossover study106 assessed the acute (1, 2.5, 4 and 6 h post dosing) cognitive and mood effects of three single doses of M. officinalis (LB 300 g, 600 g and 900 g) or matching placebo. Improvements were observed in accuracy of attention following 600 g LB and reductions in both secondary memory and working memory factors and self-rated ‘calmness’, as assessed by Bond-Lader mood scales, was elevated at the earliest time points by the lowest dose (LB 300 mg). Interestingly, alertness was significantly reduced at all time points following the highest dose. Although the research is still in its infancy, S. officinalis and M. officinalis are promising treatments for dementia.104

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Cognitively stimulating activities and psychosocial factors

Numerous epidemiological studies of activity in older adults have observed that frequent participation in cognitively stimulating activities such as reading, playing mental games and doing crossword puzzles were associated with reduced dementia risk.107,108 Psychosocial factors including emotional support, social engagements and social networks also prevent cognitive decline.22 Anxiety, depression and poor quality of life are common symptoms in the elderly population suffering from AD. Therefore, counselling and support from social networks needs to be considered as part of a holistic treatment approach.

Dietary and lifestyle advice

Human epidemiological studies provide convincing evidence that dietary patterns practised during adulthood are important contributors to age-related cognitive decline and dementia risk.109 Diets high in fat, especially trans-and saturated fats, adversely affect cognition, while those high in fruits, vegetables, cereals and fish are associated with better cognitive function and lower risk of dementia. A study110 reviewed functional food approaches to preventing chronic diseases and healthy ageing, and linked dysfunctions of the mitochondria (including membrane leakage, oxidation and release of metals) and free radical discharge to pathological events involved in cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease and carcinogenic processes. The Mediterranean diet is purported to be particularly useful for preventing the cognitive decline associated with ageing, as well as cognitive decline of the vascular and Alzheimer’s types.111 Fibre-rich foods and wheat germ oil are rich sources of tocopherols, which act as antioxidants and have anti-inflammatory actions, preventing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.12 Additionally, polyphenols found in grapes and wine possess antioxidant activity and may potentially modify certain risk factors associated with atherogenesis and cardiovascular disease. Grape-skin extracts also contain natural antioxidants such as resveratrol, catechins, myricetin, caffeic acid and rutin. There is increasing evidence to suggest that cognitive impairment and dementia in older subjects might be positively influenced by a diet including seafood. A large trial (n = 2031; 70–74 years) found that daily fish intake was associated with a lower prevalence of poor cognitive performance, and the association between total fish intake and cognition was dose-dependent with the greatest effect seen in those consuming 75 g fish per day. The effects were more pronounced for non-processed lean fish and fatty fish.112

The Mediterranean herbs such as that have been well proven for memory protection may be added to the diet Salvia officinalis and Rosmarinus officinalis.

Allium sativum decreases low-density lipoprotein (LDL), is an anti-thrombotic and suppresses platelet aggregation. Allium sativum also exhibits an antioxidant action by increasing the levels of cellular antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase, and scavenging reactive oxygen species.113 Finally, monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) consumption from olive oil (> 100 g per day) appears to be associated with a high protection against cognitive decline, though it remains unknown whether the protective effect of olive oil is due to the high MUFA intake or to the presence of antioxidant compounds in the diet or both.

Physical activity

Regular exercise can be a protective factor for cognitive decline and dementia. A study114 found that, compared with no exercise, regular physical activity was associated with lower risks of cognitive impairment and dementia, particularly AD, suggesting that regular physical activity may be an important protective factor for cognitive decline and dementia in the elderly.

Example treatment

Herbal and nutritional prescription

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

An improvement in memory should be seen 4–6 weeks after commencing the treatment, and sleep patterns would be expected to improve after 1 week. The treatment should be continued for 6–12 months and changes in cognitive function and mood, sleep and fatigue carefully monitored over time, with regular visits to a psychologist who will be able to administer neuropsychological tests and monitor changes in cognitive function. The treatment formula needs to be modified according to improvements or exacerbations in mood (thymoleptics, B vitamins), sleep (hypnotics), anxiety (nervines, anxiolytics, magnesium) and fatigue (adrenal tonics, B vitamins). By treating the insomnia, symptoms of anxiety, attention and forgetfulness are expected to improve. The treatment protocol needs to be reassessed if deterioration is observed in any aspect of cognitive function or mood. Once presenting symptoms have improved, the long-term treatment goals will be to treat (and prevent) any comorbid diseases and/or illnesses (such as arthritis, cardiovascular disease, infections and gastrointestinal function); encourage engagement in social activities and exercise; discuss changes in their ability to undertake daily tasks, future planning (such as nominating a carer if and when required) and transitional phases with the older patient.

ADDITIONAL THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Nutraceuticals

Herbal medicine

Homoeopathy

Anderson M.A. Caring for older adults holistically, 4th edn. Utah: F. A. Davis Company; 2007.

Anstey K.J., Low L.F. Normal cognitive changes in ageing. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33(10):783-787.

Ames D., et al. Cerebrovascular disease, cognitive impairment and dementia, 2nd edn. London: Informa Healthcare; 2003.

Eliopoulos C. Gerontological nursing, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

MacKenzie E.R., Rakel B. Complementary and alternative medicine for older adults. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

1. Baltes MM, Carstensen LL . Th e process of successful ageing: selection, optimization, and compensation. In: Staudinger UM, Lindenberger UER, eds. Understanding human development: dialogues with lifespan psychology. Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003.

2. Kumar P, Clark M, eds. Clinical medicine. 5th edn. London: WB Saunders, 2002.

3. Eliopoulos C. Gerontological nursing, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths, Australia 2007. Online. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3302.0. Accessed 17 December 2008.

5. World Health Organization Gender, health and ageing. 2003. Online. Available: http://www.who.int/gender/documents/en/Gender_Ageing.pdf. Accessed 5 November 2008

6. Xue C.C.L., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national population-based survey. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2007;13(6):643-650.

7. Ferri C.P., et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117.

8. Smith C., et al. National health spending in 2004: recent slowdown led by prescription drug spending. Health Affairs. 2006;25(1):186-196.

9. Heffler S., et al. Health spending projections for 2001–2011: the latest outlook. Health Affairs. 2002;21(2):207-218.

10. Brownie S. Why are elderly individuals at risk of nutritional deficiency? International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2006;12(2):110-118.

11. Gennari C. Calcium and vitamin D nutrition and bone disease of the elderly. Public Health Nutrition. 2001;4(2 B):547-559.

12. Remacle C. Functional foods, ageing and degenerative disease. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2004.

13. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phyto therapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

14. Campbell A.J., et al. Incontinence in the elderly: prevalence and prognosis. Age Ageing. 1985;14(2):65-70.

15. Gooneratne N.S. Complementary and alternative medicine for sleep disturbances in older adults. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2008;24(1):121-138.

16. Luanaigh C.Ã., Lawlor B.A. Loneliness and the health of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1213-1221.

17. Foley D.J., et al. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18(6):32-425.

18. Ancoli-Israel S., et al. Sleep in the elderly: Normal variations and common sleep disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2008;16(5):279-286.

19. Foley D., et al. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56(5):497-502.

20. Montorio I., Izal M. The geriatric depression scale: a review of its development and utility. International Psychogeriatrics. 1996;8(1):103-112.

21. Anderson M.A. Caring for older adults holistically, 3rd edn. Utah: F. A. Davis Company; 2003.

22. Hendrie H.C., et al. The NIH Cognitive and Emotional Health Project. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2006;2(1):12-32.

23. Riddle D.R., Schindler M.K. Brain aging research. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2007;17(4):225-239.

24. Anstey K.J., Low L.F. Normal cognitive changes in aging. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33(10):783-787.

25. Qualls S.H., Smyer M.A. Changes in decision-making capacity in older adults: assessment and intervention. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008.

26. Kalaria R.N., et al. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurology. 2008;7(9):812-826.

27. Thal D.R., Del Tredici K., Braak H. Neurodegeneration in normal brain aging and disease. Science of aging knowledge environment. Sci Aging Knowl Environ. 2004;23:26.

28. Akhtar S., et al. Are people with mild cognitive impairment aware of the benefits of errorless learning? Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2006;16(3):329-346.

29. Palmer K., et al. Early symptoms and signs of cognitive deficits might not always be detectable in persons who develop Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(2):252-258.

30. Flicker L. Vascular factors in geriatric psychiatry: time to take a serious look. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2008;21(6):551-554.

31. Folstein M.F., et al. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

32. Rosen W.G., et al. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141(11):1356-1364.

33. Fioravanti M., et al. The Italian version of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS): psychometric and normative characteristics from a normal aged population. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1994;19(1):21-30.

34. Erkinjuntti T., et al. The effect of different diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of dementia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(23):1667-1674.

35. Whitmer R.A., et al. Central obesity and increased risk of dementia more than three decades later. Neurology. 2008;71(14):1057-1064.

36. Jagust W., et al. Central obesity and the aging brain. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62(10):1545-1548.

37. Pavlovic D.M., Pavlovic A.M. Dementia and diabetes mellitus. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo. 2008;136(3–4):170-175.

38. Xu G., et al. Alcohol consumption and transition of mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2008;63(1):43-49.

39. Pedelty L., Gorelick P.B. Management of hypertension and cerebrovascular disease in the elderly. American Journal of Medicine. 2008;121(8 Suppl 1):S23-S31.

40. Duron E., Hanon O. Vascular risk factors, cognitive decline, and dementia. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2008;4(2):363-381.

41. Milionis H.J., et al. Metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: a link to a vascular hypothesis? CNS Spectrums. 2008;13(7):606-613.

42. Seignourel P.J., et al. Anxiety in dementia: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1071-1082.

43. Grutzendler J., Morris J.C. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs. 2001;61(1):41-52.

44. Mukherjee P.K., et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from plants. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:289-300.

45. Pratt R.D., et al. Donepezil: tolerability and safety in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(9):710-717.

46. Houghton P.J., Howes M.J. Natural products and derivatives affecting neurotransmission relevant to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. NeuroSignals. 2005;14(1–2):6-22.

47. Desai A.K., Grossberg G.T. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2005;64(12 Suppl 3):S34-S39.

48. Reynolds J., et al. Retarding cognitive decline with science-based nutraceuticals. JAMA. 2008;11(1):23-31.

49. Mariani E., et al. Oxidative stress in brain aging, neurodegenerative and vascular diseases: an overview. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;827(1):65-75.

50. Polidori M.C. Antioxidant micronutrients in the prevention of age-related diseases. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2003;49:229-235.

51. Engelhart M., et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287(24):3223-3229.

52. Morris M.C., et al. Vitamin E and vitamin C supplement use and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1998;12(3):121-126.

53. Tuppo E.E., et al. Sign of lipid peroxidation as measured in the urine of patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54(5):565-568.

54. Ryan J., et al. An examination of the effects of the antioxidant Pycnogenol® on cognitive performance, serum lipid profile, endocrinological and oxidative stress biomarkers in an elderly population. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22(5):553-562.

55. Mishra S., Palanivelu K. The effect of curcumin (turmeric) on Alzheimer’s disease: an overview. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2008;11(1):13-19.

56. Bisson J.F., et al. Effects of long-term administration of a cocoa polyphenolic extract (Acticoa powder) on cognitive performances in aged rats. British Journal of Nutrition. 2008;100(1):94-101.

57. Faridi Z., et al. Acute dark chocolate and cocoa ingestion and endothelial function: a randomized controlled crossover trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;88(1):58-63.

58. Sorond F.A., et al. Cerebral blood flow response to flavanol-rich cocoa in healthy elderly humans. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2008;4(2):433-440.

59. Francis S.T., et al. The effect of flavanol-rich cocoa on the fMRI response to a cognitive task in healthy young people. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2006;47(Suppl 2):S215-S220.

60. Liu J. The effects and mechanisms of mitochondrial nutrient alpha-lipoic acid on improving age-associated mitochondrial and cognitive dysfunction: an overview. Neurochemical Research. 2008;33(1):194-203.

61. Ishrat T., et al. Coenzyme Q10 modulates cognitive impairment against intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;171(1):9-16.

62. Bragin V., et al. Integrated treatment approach improves cognitive function in demented and clinically depressed patients. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2005;20(1):21-26.

63. Hager K., et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a new treatment option for Alzheimer type dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2001;32(3):275-282.

64. Passeri M., et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine in the treatment of mildly demented elderly patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1990;10(1–2):75-79.

65. Rai G., et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acetyl-l-carnitine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 1990;11(10):638-647.

66. Hudson S., Tabet N. Acetyl-L-carnitine for dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (2):2003. CD003158

67. Sun Y.X., et al. Inflammatory markers in matched plasma and cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16(3):136-144.

68. Stough C., et al. Examining the nootropic effects of a special extract of Bacopa monniera on human cognitive functioning: 90 day double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(12):1629-1634.

69. Holcomb L.A., et al. Bacopa monniera extract reduces amyloid levels in PSAPP mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(3):243-251.

70. Channa S., et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of Bacopa monniera in rodents. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104(1–2):286-289.

71. Bhattacharya S.K., Ghosal S. Anxiolytic activity of a standardized extract of Bacopa monniera: an experimental study. Phytomedicine. 1998;5(2):77-82.

72. Sairam K., et al. Antidepressant activity of standardized extract of Bacopa monniera in experimental models of depression in rats. Phytomedicine. 2002;9(3):207-211.

73. Rai D., et al. Adaptogenic effect of Bacopa monniera (brahmi). Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75(4):823-830.

74. Roodenrys S., et al. Chronic effects of brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) on human memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:279-281.

75. Stough C., et al. The chronic effects of an extract of Bacopa monnieri (brahmi) on cognitive function in healthy human subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;156(4):481-484.

76. Calabrese C., et al. Effects of standardized Bacopa monnieri extract on cognitive performance, anxiety, and depression in the elderly: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(6):707-713.

77. Alagiakrishnan K., et al. Treating vascular risk factors and maintaining vascular health: is this the way towards successful cognitive ageing and preventing cognitive decline? Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2006;82(964):101-105.

78. Hanon O., et al. Relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in elderly subjects with complaints of memory loss. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2193-2197.

79. Malouf R., Grimley Evans J. Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for the prevention and treatment of healthy elderly and demented people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (4):2008. CD004514

80. Morris M.C., et al. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with age-related cognitive change. Neurology. 2006;24;(8):1370-1376. 67

81. Atwood C.S., et al. Role of free radicals and metal ions in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Met Ions Biol Syst. 1999;36:309-364.

82. Cuajungco M.P., et al. Metal chelation as a potential therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:292-304.

83. Hatcher H., et al. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2008;65(11):1631-1652.

84. Bartres-Faz D., et al. Apo E influences declarative and procedural learning in age-associated memory impairment. Neuroreport. 1999;10(14):2923-2927.

85. Sørensen H., Sonne J. A double-masked study of the effects of ginseng on cognitive functions. Current Therapeutic Research—Clinical and Experimental. 1996;57(12):959-968.

86. Wiklund I., et al. A double-blind comparison of the effect on quality of life of a combination of vital substances including standardized ginseng G115 and placebo. Current Therapeutic Research—Clinical and Experimental. 1994;55(1):32-42.

87. Kennedy D.O., et al. Dose dependent changes in cognitive performance and mood following acute administration of ginseng to healthy young volunteers. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2001;4(4):295-310.

88. Kennedy D.O., et al. Differential, dose dependent changes in cognitive performance following acute administration of a Ginkgo biloba/Panax ginseng combination to healthy young volunteers. Nutr Neurosci. 2001;4(5):399-412.

89. Smith P.F., et al. The neuroprotective properties of the Ginkgo biloba leaf: a review of the possible relationship to platelet-activating factor (PAF). J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;50(3):131-139.

90. Maitra I. Peroxyl radical scavenging activity of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49(11):1649-1655.

91. Kristofikova Z., Klaschka J. In vitro effect of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) on the activity of presynaptic cholinergic nerve terminals in rat hippocampus. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1997;8(1):43-48.

92. Gold P.E. Ginkgo biloba A cognitive enhancer? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2002;3(1):2-11.

93. Stough C., et al. Neuropsychological changes after 30-day Ginkgo biloba administration in healthy participants. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;4(2):131-134.

94. Elsabagh S., et al. Differential cognitive effects of Ginkgo biloba after acute and chronic treatment in healthy young volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;179(2):437-446.

95. Kennedy D.O., et al. The dose-dependent cognitive effects of acute administration of Ginkgo biloba to healthy young volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;151(4):416-423.

96. Nathan P.J., et al. The acute nootropic effects of Ginkgo biloba in healthy older human subjects: a preliminary investigation. Human Psychopharmacology. 2002;17(1):45-49.

97. Mix J.A., Crews W.D.Jr. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 in a sample of cognitively intact older adults: neuropsychological findings. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17(6):267-277.

98. Le Bars P.L., et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia. North American EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1327-1332.

99. Le Bars P.L., et al. A 26-week analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 in dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11(4):230-237.

100. Wettstein A. Cholinesterase inhibitors and gingko extracts—are they comparable in the treatment of dementia? Comparison of published placebo-controlled efficacy studies of at least six months’ duration. Phytomedicine. 2000;6(6):393-401.

101. DeKosky S.T., et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2253-2262.

102. Nathan P.J., et al. Effects of a combined extract of Ginkgo biloba and Bacopa monniera on cognitive function in healthy humans. Human Psychopharmacology. 2004;19:91-96.

103. Birks J., Grimley Evans J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (1):2008. CD003120

104. Kennedy D.O., Scholey A.B. The psychopharmacology of European herbs with cognition-enhancing properties. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(35):4613-4623.

105. Akhondzadeh S., et al. Salvia officinalis extract in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A double blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2003;28(1):53-59.

106. Kennedy D.O., et al. Modulation of mood and cognitive performance following acute administration of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm). Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;72(4):953-964.

107. Wilson R.S. Participation in cognitively stimulating activites and risk of incident Alzheimer Disease. JAMA. 2002;287(6):742-748.

108. Wilson R.S., et al. Relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(20):1911-1920.

109. Parrott M.D., Greenwood C.E. Dietary influences on cognitive function with aging: from high-fat diets to healthful eating. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1114:389-397.

110. Ferrari C.K.B. Functional foods, herbs and nutraceuticals: towards biochemical mechanisms of healthy aging. Biogerontology. 2004;5(5):275-289.

111. Panza F., et al. Mediterranean diet and cognitive decline. Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7(7):959-963.

112. Nurk E., et al. Cognitive performance among the elderly and dietary fish intake: the Hordaland Health Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;86(5):1470-1478.

113. Qi R., Wang Z. Pharmacological effects of garlic extract. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2003;24(2):62-63.

114. Laurin D., et al. Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons. Archives of Neurology. 2001;58(3):498-504.

115. Uauy R., Dangour A.D. Nutrition in brain development and aging: Role of essential fatty acids. Nutrition Reviews. 2006;64(5 Pt 2):S24-S33.

116. Kalmijn S., et al. Dietary intake of fatty acids and fish in relation to cognitive performance at middle age. Neurology. 2004;62(2):275-280.

117. van de Rest O., et al. Effect of fish oil on cognitive performance in older subjects: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2008;71(6):430-438.

118. Huang T.L., et al. Benefits of fatty fish on dementia risk are stronger for those without APOE epsilon4. Neurology. 2005;65(9):1409-1414.

119. Freund-Levi Y., et al. Omega-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study—a randomized double-blind trial. Archives of Neurology. 2006;63(10):1402-1408.

120. Choi Y., et al. The green tea polyphenol (–)-epigallocatechin gallate attenuates beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Life Sciences. 2001;70(5):603-614.

121. Weinreb O., et al. A novel approach of proteomics and transcriptomics to study the mechanism of action of the antioxidant–iron chelator green tea polyphenol (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;43(4):546-556.

122. Mandel S., et al. Green tea catechins as brain-permeable, natural iron chelators—antioxidants for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50(2):229-234.

123. Kuriyama S., et al. Green tea consumption and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study from the Tsurugaya Project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):355-361.

124. Dhanasekaran M., et al. Centella asiatica extract selectively decreases amyloid beta levels in hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;23(1):14-19.

125. Wattanathorn J., et al. Positive modulation of cognition and mood in the healthy elderly volunteer following the administration of Centella asiatica. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(2):325-332.

126. McCarney R., et al. Homeopathy for dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (1):2003. CD003803