214 Age-related macular degeneration (senile macular degeneration)

Salient features

History

• Often visual loss is detected when one eye is covered for testing visual acuity

• Loss of ability to read, recognize faces or drive a car; however, patients have enough peripheral vision to walk unaided

• Decrease in visual acuity (severe loss suggests choroidal neovascularization)

• Metamorphosia (distortion of the shape of objects in view)

• Variable visual loss from atrophy of a large area of retinal pigment epithelium involving the fovea

Examination

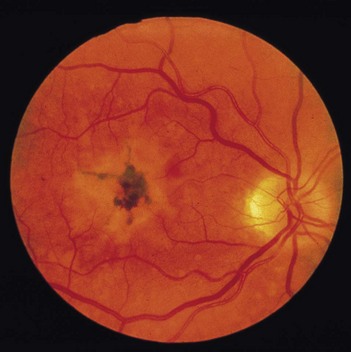

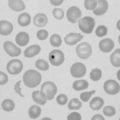

• Disruption of pigment of the retinal pigment epithelium into small areas of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation (Fig. 214.1)

• Comment on the white walking aid by the bedside, which indicates the patient is registered blind.

• Check visual acuity and visual field (in most patients there is loss of central vision and maintenance of peripheral vision). Patients with only drüsen typically require additional magnification of text and more intense light to read small print text.

• Tell the examiner you would like to use Amsler grid to confirm your diagnosis.

Questions

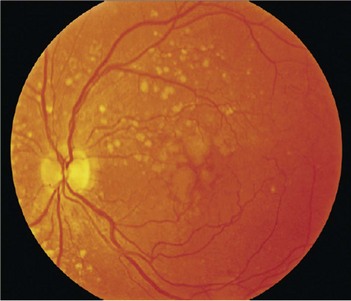

What are drüsen?

Drüsen are pale yellow spots that occur individually or in clusters throughout the macula (Fig. 214.2). Nearly all individuals over the age of 50 years of age have at least one small drüsen (≤63 µm) in one or both eyes (Opthalmology 1992;14:130–42). They consist of amorphous material accumulated between the Bruch’s membrane and pigment epithelium. Although the exact origin is not known, it is believed that drüsen occur from accumulation of lipofuscin and other cellular debris derived from cells of the retinal pigment epithelium that are compromised by age and other factors. Only eyes with large drüsen (>63 µm) are at increased risk for senile macular degeneration (Opthalmology 1997;104:7–21). The clinical hallmark and usually the first clinical finding of age-related macular degeneration is the presence of drüsen. In most cases of age-related macular degeneration, drüsen are present bilaterally.

What are the types of age-related macular degeneration?

There are three types (Lancet 2008; 372:1835–45):

Early age-related macular degeneration. Multiple small drüsen (<63 µm) or intermediate drüsen (63–125 µm) with no evidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration.

Intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Extensive intermediate drüsen or large drüsen (≥125 µm) with no evidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration.

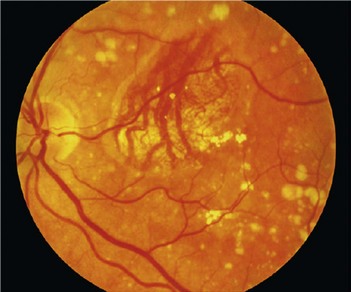

Advanced age-related macular degeneration. The presence of one or other of geographic atrophy or neovascular age-related macular degeneration:

Advanced-level questions

What are the risk factors for choroidal neovascularization in the other eye of a patient with disorder in one eye?

What therapies are available for age-related macular degeneration?

• Life style: cessation of tobacco, high dietary intake of beta-carotene, vitamins C and E and zinc, as well as high dietary intake of n3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish. Antioxidant vitamins and zinc can reduce the risk of developing advanced age-related macular degeneration by about a quarter in those at least at moderate risk.

• When visual loss is severe, low-vision devices such as electronic video magnifiers and spectacle-mounted telescopes, as well as low-vision rehabilitation services are available.

• Ranibizumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits all forms of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). When ranibizumab is injected into the vitreous it has stabilized loss of vision and, in some cases, improved vision in individuals with neovascular age-related macular degeneration.

• Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody to VEGF used intravenously as an anticancer agent, is also increasingly being used off-label as intravitreal therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration.

• Photodynamic to reduce angiogenesis involves the use of an intravenously administered light-sensitive dye, verteporfin (Visudyne, Novartis), that preferentially concentrates in new blood vessels and is activated with the use of a 689 nm laser beam focused over the macula. It causes localized choroidal neovascular thrombosis through a non-thermal chemotoxic reaction.

• Pegaptanib, an anti-VEGF therapy, appears to be effective.

• Triple therapy: intravitreal anti-VEGF agent, intravitreal dexamethasone and photodynamic therapy is also currently under investigation.

• Adenoviral vector-mediated intravitreal gene transfer of pigment-epithelium-derived factor (an antiangiogenic cytokine) appears to help to arrest the growth of choroidal neovascularization.

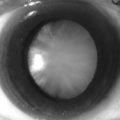

• Implantation of artificial intraocular devices (miniature telescopes) might improve the quality of life of patients with severe visual loss from end-stage disease.

• Implantation of electrical stimulated devices targeting the optic nerve and cortical, subretinal and epiretinal areas has led to the perception of phosphenes (discrete, reproducible perceptions of light) and is under investigation.

How is the neovascularization treated?

• Laser photocoagulation of regions outside the foveal avascular zone

• Subfoveal neovascularization: photocoagulated is associated with a treatment-induced visual loss immediately but in the long term is found to be beneficial. Treatment may have to be deferred in those with good initial visual acuity because a large scotoma occurs as a result of treatment

• Photodynamic therapy: with photosensitizers such as verteporfin

• Interferon-alfa: currently being evaluated

• Submacular surgery to remove the subfoveal choroidal neovascularization: reported to be useful, but the results are not as good as laser photocoagulation

• Zinc as a therapeutic agent for macular degeneration: has not been evaluated in a rigorous trial

• External beam radiation therapy

• Others: indocyanine green-guided laser treatment, retinal transplantation and transplantation of retinal pigment epithelium, retinal translocation, retinal prosthesis, gene therapy.