chapter 6

After the History and Examination, What Next?

Upon completing the history and examination, the next step is determined by the following factors:

• the availability of tests to confirm or exclude certain diagnoses

• the potential complications of those tests

• the severity and level of urgency in terms of the consequences of a particular illness not being diagnosed and treated promptly

• the benefit versus risk profile of any potential treatment

• the presence of any social factors or past medical history that could influence a course of action or treatment in this particular patient.

This chapter will discuss each of these aspects and how they influence the course of action.

LEVEL OF CERTAINTY OF DIAGNOSIS

There are three possible scenarios:

1. A particular diagnosis seems obvious.

2. One particular diagnosis is not apparent, and there are several possible diagnoses.

A particular diagnosis seems certain

In most instances the diagnosis is apparent. In the general practice setting almost 90% of diagnoses are established at the completion of the history and examination [1]. In one outpatient clinic this figure was 73% (history 56% and examination 17%) in patients with cardiovascular, neurological, respiratory, urinary and other miscellaneous problems [2]. In patients with neurological problems the initial diagnosis is less obvious and was correct in only 60% of patients presenting to an emergency department [3]. In this setting the appropriate course of action is to initiate investigations that can confirm the diagnosis, exclude alternative diagnoses with potentially more severe adverse outcomes and institute a plan of management taking into account factors in the past, social and medical drug history that would influence management in this particular patient.

A word of caution: being absolutely certain is potentially the most dangerous scenario. Doctors are strongly anchored by their initial diagnoses [4] (see Case 6.1) and are at risk of closing their minds to possible alternatives, often in the presence of clinical features or results from investigations that should raise doubt about the diagnosis.

Doctors recognise patterns of familiar problems with respect to critical cues [6]. Doctors who are more experienced appear to weigh their first impressions more heavily than those who are less experienced and at risk of closing their minds early on in the diagnostic process [7]. Even experienced clinicians may be unaware of the correctness of their diagnoses when they initially make them [8].

If there are tests to confirm the diagnosis, it is appropriate to perform those tests, provided the patient is informed of the risks associated with them. When ordering tests and reviewing the results, it is most important to be aware of the sensitivity and specificity and the influence of the prevalence of the disease on the positive predictive value and the negative predictive value of those tests [9] (for a discussion of these concepts, refer to the section ‘Understanding and interpreting test results’ below).

There are several possible diagnoses

It is imperative to keep the diagnostic options open by making provisional diagnoses while keeping alternatives in mind. Be circumspect and take action to minimise the possibility of missing other critical diagnoses [10]. Once again, if there are tests that can differentiate one particular diagnosis from another, it would be most appropriate to perform those tests. If a specific diagnosis cannot be made following the investigations, the approach is similar to that discussed in the following section.

You have no idea what is wrong

In the setting of uncertainty there are several possible courses of action. A particularly useful strategy is to start again: take a more detailed history and repeat the examination.1 This is the approach recommended when you have absolutely no idea what the diagnosis is. In this situation performing many tests is often misleading because of the sensitivity and specificity of tests.

These various approaches will be discussed in terms of their relative merits and deficiencies.

WAIT AND SEE

In resolving uncertainty, time is a very powerful diagnostic tool. The idea is to wait for a period of time in the hope that the diagnosis becomes clear or the patient gets better [10], [11]. The effective use of this approach requires considerable skill, however. Often in this situation a doctor may order unnecessary tests in the hope that a diagnosis may be established; most often it is not. If the ‘wait and see’ approach is adopted, it is important to:

• inform the patient that there is uncertainty

• advise them of the possible outcomes

• recommend that they report immediately should symptoms worsen or if any new symptoms develop.

Shared medical decision making is a process in which patients and providers consider outcome probabilities and patient preferences and reach a healthcare decision based on mutual agreement. Shared decision making is best employed for problems involving medical uncertainty [12]. However, it is important to consider the fact that not all patients wish to be involved in shared medical decisions [13].

UNDERTAKE INVESTIGATIONS

There is a more detailed discussion of investigations later in this chapter.

OBTAIN A SECOND OPINION

Although doctors prefer to obtain information from journals and books, they often consult colleagues to get answers to clinical and research questions [14], [15]. Even for doctors whose first choice of information source was the medical literature – either books or journals – the most frequent second choice was consultations [14].

In a study of 254 referrals seen by a neurologist there was a significant change in diagnosis in 55%, and in management in nearly 70% [16].

There are several ways of obtaining a second opinion:

• the ‘informal consultation with a colleague’

• the ‘curbside’ conversation in the corridor without actually seeing the patient

• presenting at meetings and seeking several opinions, often but not invariably with the patient at the meeting

• the ‘formal second opinion’ when a colleague is asked to see the patient.

Telephone advice: Telephoning a colleague for advice is common. The recipient of the call is in a very difficult situation as providing the correct advice very much depends on being given the correct history and examination findings. An experienced clinician often knows the particular questions to ask and can decide if and when they should actually see the patient. It is probably wiser for an inexperienced clinician to arrange to formally see the patient in consultation.

Corridor or curbside consultation: ‘Corridor or curbside consultation’ is another approach used often [17]. Unfortunately, and sometimes with dire consequences, this is used by medical practitioners to seek informal advice about their own medical problems. The model of a good curbside consultation ‘is to say what you know and what you don’t know. Then you hope the person you are consulting with will treat you with respect’ [17]. Requesting doctors who could not present relevant information, frame a clear question or answer consultant questions in a well-informed manner were generally asked to formally refer the patient [17]. Perley et al [17] commented that tacit rules govern curbside consultation interactions, and negative consequences result when the rules are misunderstood or not observed.

Once again, the correct advice very much depends on being given the correct information. The neurologist providing advice will want to know the mode of onset and progression of the symptoms of the current illness together with the EXACT nature and distribution of the symptoms and the abnormal neurological signs, if present. It is difficult for inexperienced clinicians to perform detailed neurological examinations but there should be no reason why, as outlined in Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’, an inexperienced clinician cannot obtain a detailed history. Finally, the neurologist would want information about the social, past and drug history that may influence any subsequent course of action.

Clinical meetings: Second opinions are often sought for the purpose of diagnosis and/or treatment in clinical meetings. There is the perception that one is obtaining multiple opinions. Although this can be a valuable tool, particularly if one of the participants identifies the problem, in a more complex case often what is said in meetings is very different to what is said in a formal consultation. Thus, the advice obtained in clinical meetings should be viewed circumspectly. A brain biopsy is often recommended in clinical meetings, but not often performed despite the recommendation.2

The formal second opinion: The formal second opinion is probably the most effective method of dealing with diagnostic or therapeutic uncertainties. There is no shame in asking a colleague to formally see the patient for a second opinion. If you do, it can be a learning experience; if you do not and the patient perceives a lack of progress, they will independently seek a second opinion and you will miss out on a learning opportunity. If a patient requests a second opinion, NEVER hesitate to arrange one.

SEARCH THE INTERNET

An increasingly popular and useful strategy is to search the Internet3 [18–20]. Patients frequently look for answers on the internet [21]. In the author’s own experience many patients bring the results of their searches to the consultation. In one study [19] Google was able to make the correct diagnosis in 58% of the cases in the New England Journal of Medicine clinical-pathological conferences. In a comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar, the keyword search function of PubMed was superior. While Google Scholar could retrieve the most obscure of information, its use was marred by inadequate and less frequently updated citation information [22]. Searching in Google Scholar can be refined by adding + emedicine to the search [23]. For example, ‘trigeminal neuralgia’ yields 48,000 ‘hits’ while ‘trigeminal neuralgia + emedicine’ retrieves 478 references. Many remain skeptical [24] and, as recently as 2 years ago, Twisselmann stated that the jury is still out on whether searching for symptoms on the Internet is the way forward for doctors and consumers [25].

The author has adopted the practice of frequently consulting the Internet even in the midst of a formal consultation.4 It is a useful way to look for any new advances in therapy, to provide information to the patient or referring practitioner by adding the abstracts and references to the letter or even to search for an obscure diagnosis (see Case 6.2).

An online information retrieval system [27] was associated with a significant improvement in the quality of answers provided by clinicians to typical clinical problems. In a small proportion of cases, use of the system produced errors [27]. Despite ready access to the Internet many doctors do not yet use it in a just-in-time manner to immediately solve difficult patient problems but instead continue to rely on consultation with colleagues [28, 29]. One major obstacle is the time it takes to search for information. Other difficulties primary care doctors experience are related to formulating an appropriate search question, finding an optimal search strategy and interpreting the evidence found [29].

Computer programs that can be used as an aid in diagnosing multiple congenital anomaly syndromes have been used for many years and are designed to aid the paediatrician diagnose rare disorders in children [30]. Other computer-aided software systems for diagnosing neurological diseases exist [31], and it is likely that more software will be developed in the future. Such software will always be dependent upon the information provided by the user.

AVAILABILITY OF TESTS TO CONFIRM OR EXCLUDE CERTAIN DIAGNOSES

This section discusses the general principles of investigations or tests. Essentially it will cover why tests give the ‘wrong’ or unexpected result and what to do when this occurs. There are many excellent books that discuss the interpretation of tests in great detail [32–34].

Understanding and interpreting test results

SENSITIVITY, SPECIFICITY, POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE PREDICTIVE VALUES

• Sensitivity refers to how good a test is at correctly identifying people who have the disease.

• Specificity is concerned with how good the test is at correctly excluding people who do not have the condition.

• Positive predictive value refers to the chance that a positive test result will be correct.

• Negative predictive value is concerned only with negative test results.

Table 6.1 shows the results of a test with a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 80%. When the test is performed on 100 patients with the suspected diagnosis, 10 patients with the diagnosis will have a negative test while 20 patients who do not have that particular diagnosis will have an incorrect positive test. The ideal test would be one with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity, but this does not occur.

TABLE 6.1

| +ve Test | −ve Test | |

| Patient has disease | 90 | 10 |

| Patient does not have disease | 20 | 80 |

The pre-test likelihood of a patient having a particular diagnosis also greatly influences how a test result should be interpreted. Using the same values for sensitivity and specificity, if 100 patients are tested for a particular diagnosis when only 50 of them have that diagnosis (see Table 6.2), a positive test will detect 45 of the patients with the disease (90% of 50) but the test will also be positive in 10 (20% of 50) patients who do not have the disease!

TABLE 6.2

| +ve Test | −ve Test | |

| Patient has disease | 45 | 5 |

| Patient does not have disease | 5 | 45 |

If the prior probability of a particular diagnosis being present is even lower, the results will be even more dramatic. If the patient is very unlikely to have the disease, say a 10% chance (i.e. 10 in every 100 patients tested), with the same sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 80%, respectively, a positive result will correctly identify 9 patients with the disease but will incorrectly diagnose 18 patients without the disease (90% of 10 = 9 and 20% of 90 = 18). The rarer the problem, the more certain we can be that a negative test excludes that disease, but less certain that a positive test indicates an abnormality (see Table 6.3).

TABLE 6.3

| +ve Test | −ve Test | |

| Patient has disease | 9 | 1 |

| Patient does not have disease | 18 | 72 |

The variability in prevalence of a particular disease between one study and another means that predictive values found in one study do not apply universally [35]. A common practice of inexperienced doctors is to repeat borderline abnormal tests simply because the result is ‘outside the normal range’ even when the test result is irrelevant to the clinical problem. In this situation it is better to discuss the result with the relevant pathologist or radiologist.

THE POSSIBLE COMPLICATIONS OF TESTS

There are very few tests that are not associated with risk. Venesection is perfectly safe in close to 100% of patients but rarely can be associated with injury to a nerve that can result in long-term pain and dysaesthesia. Although this complication is extremely rare (<0.02% [36]), the result can be very distressing.

When ordering any investigation it is important to consider the potential complications of the test in relation to the seriousness of the illness that is being investigated. A patient with a life-threatening illness might be willing to consider a potentially life-threatening investigation if it could make a significant difference; on the other hand, a patient with symptoms without disability would be concerned about any investigation that might cause harm.

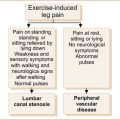

SEVERITY AND URGENCY: THE POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES OF A PARTICULAR ILLNESS NOT BEING DIAGNOSED AND TREATED

The difficulty arises in the patient with a neurological problem when there is uncertainty as to the diagnosis. There is very little in the literature that can provide guidance in this area. Scoring tools for priority setting for general surgery and hip and knee surgery were useful but were not particularly good for MRI scanning [37]. The discussion below contains observations made by this author during many years of clinical practice and observations from colleagues who were asked specifically, ‘What do you think constitutes an urgent problem?’

The overriding principle is to consider the worst case scenario. It is prudent to consider the most serious possible diagnosis that, if left untreated, could result in significant morbidity or mortality. This will dictate the ‘level of urgency’ and how promptly a doctor should act (see Case 6.3).

• Rapidly evolving weakness dictates immediate action.

• Although not all patients with symptoms related to the spinal cord have urgent neurological problems, disorders in this region can result in devastating neurological deficits and the degree of recovery is very dependent on the severity of the spinal cord lesion [38]. The investigations should be prompt if one suspects spinal cord disease.5 One would consider spinal cord problems with leg weakness and, particularly if there is associated sphincter disturbance, with bilateral leg weakness if the lesion is in the thoracic spinal cord and four-limb weakness if the lesion is in the cervical spinal cord.

• Similarly, patients with symptoms related to the brainstem such as diplopia, dysphagia and vertigo, particularly if combined with ataxia or limb weakness, should be investigated as a matter of urgency.

• Patients with recurrent symptoms within a short period of time should also be dealt with as a matter of urgency. As a general rule, symptoms of weakness are more likely to imply significant neurological problems rather than isolated sensory symptoms.

• Similarly, symptoms associated with loss of function are more likely to be significant than symptoms without functional loss. Patients with multiple symptoms not associated with any loss of function, particularly if also associated with non-neurological symptoms, are less likely to have a serious illness requiring urgent intervention. Transient symptoms lasting seconds are also unlikely to be of any significance. One study found that higher numbers of physical symptoms and the complaint of pain were indicators of possible non-organic disease [39].

A summary of urgent and non-urgent presentations is given in Table 6.4. A simple rule is: ‘if in doubt do not hesitate to ask for help’.

TABLE 6.4

Some urgent and non-urgent clinical presentations

| Very urgent | Less urgent |

| LOC | Symptoms lasting seconds |

| Status epilepticus | Symptoms without functional loss |

| Recurrent symptoms within a short period | Isolated sensory symptoms |

| Intermittent symptoms affecting multiple organ systems as well as the nervous system |

THE BENEFIT VERSUS RISK PROFILE OF ANY POTENTIAL TREATMENT

• Most patients can tolerate most drugs with few or no side effects. When a diagnosis is clearly established, the choice of the appropriate treatment would primarily be dictated by the knowledge that one particular therapy has greater efficacy than another.

• On the other hand, if there are several treatments with equal efficacy, the choice of therapy would then depend on the risk profile and the patient’s willingness to consider particular side effects. For example, there may be two or three drugs that could be used to treat a patient who suffers from epilepsy; the drugs that may cause weight gain or interfere with the oral contraceptive pill would be most unacceptable to a young female patient.

• In the setting where the diagnosis is uncertain and one is instituting empirical therapy, it is important to inform the patient of the perceived benefits of the therapy prescribed but also to alert the patient to the potential risks of that therapy. More importantly, carefully monitor the response to therapy and be willing to reconsider the diagnosis and/or choice of therapy.

SOCIAL FACTORS AND PAST MEDICAL PROBLEMS THAT MAY INFLUENCE A COURSE OF ACTION OR TREATMENT

This has already been discussed briefly in Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’, where the importance of not using information about the past history, family history and social history to make a diagnosis was stressed. Once a diagnosis is established, however, the subsequent management of the patient is very much influenced by their past medical history, their social circumstances and, more importantly, the drugs that they are currently taking.

• Ten to thirty per cent of admissions to hospital are due to iatrogenic drug-related problems [40, 41]. Computer software can alert clinicians to the potential for drug interactions and should be consulted when prescribing a new medication.

• Other medical problems will have a major impact on subsequent management and may limit the therapeutic options as a choice of therapy could be contraindicated in that condition.

• Similarly, an elderly patient who has the support of spouse and family can be managed at home as opposed to the patient who has no support and who develops an illness that would prevent them from living independently.

REFERENCES

1. Crombie, D.L. Diagnostic process. J Coll Gen Pract. 1963;6:579–589.

2. Sandler, G. Costs of unnecessary tests. BMJ. 1979;2(6181):21–24.

3. Moeller, J.J., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of neurological problems in the emergency department. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35(3):335–341.

4. Berner, E.S., et al. Clinician performance and prominence of diagnoses displayed by a clinical diagnostic decision support system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:76–80.

5. Gregoire, S.M., et al. Polymerase chain reaction analysis and oligoclonal antibody in the cerebrospinal fluid from 34 patients with varicella-zoster virus infection of the nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(8):938–942.

6. Coughlin, L.D., Patel, V.L. Processing of critical information by physicians and medical students. J Med Educ. 1987;62(10):818–828.

7. Eva, K.W., Cunnington, J.P. The difficulty with experience: Does practice increase susceptibility to premature closure? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(3):192–198.

8. Friedman, C.P., et al. Do physicians know when their diagnoses are correct? Implications for decision support and error reduction. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):334–339.

9. Loong, T.W. Understanding sensitivity and specificity with the right side of the brain. BMJ. 2003;327(7417):716–719.

10. Hewson, M.G., et al. Strategies for managing uncertainty and complexity. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(8):481–485.

11. Sloane, P.D., et al. Introduction to clinical problems. In: Sloane P.D., Slatt L.M., Ebell M.H., Jacques L.B., Smith M.A., eds. Essentials of family medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:126.

12. Frosch, D.L., Kaplan, R.M. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: Past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17(4):285–294.

13. Levinson, W., et al. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):531–535.

14. Haug, J.D. Physicians’ preferences for information sources: A meta-analytic study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997;85(3):223–232.

15. Campbell, E.J. Use of the telephone in consultant practice. BMJ. 1978;2(6154):1784–1785.

16. Roberts, K., et al. What difference does a neurologist make in a general hospital? Estimating the impact of neurology consultations on in-patient care. Ir J Med Sci. 2007;176(3):211–214.

17. Perley, C.M. Physician use of the curbside consultation to address information needs: Report on a collective case study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(2):137–144.

18. Maulden, S.A. Information technology, the internet, and the future of neurology. Neurologist. 2003;9(3):149–159.

19. Tang, H., Ng, J.H. Googling for a diagnosis – use of Google as a diagnostic aid: Internet based study. BMJ. 2006;333(7579):1143–1145.

20. Yu, H., Kaufman, D. A cognitive evaluation of four online search engines for answering definitional questions posed by physicians. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2007:328–339.

21. Shuyler, K.S., Knight, K.M. What are patients seeking when they turn to the Internet? Qualitative content analysis of questions asked by visitors to an orthopaedics web site. J Med Internet Res. 5(4), 2003. [e24].

22. Falagas, M.E., et al. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22(2):338–342.

23. Taubert, M. Use of Google as a diagnostic aid: Bias your search. BMJ. 333(7581), 2006. [1270; author reply 1270].

24. Rapid responses. Googling for a diagnosis – use of Google as a diagnostic aid: Internet based study. 2006. Available: www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/333/7579/1143 (1 Dec 2009).

25. Twisselmann, B. Use of Google as a diagnostic aid: Summary of other responses. BMJ. 2006;333(7581):1270–1271.

26. Conley, S.F., Beecher, R.B., Marks, S. Stress velopharyngeal incompetence in an adolescent trumpet player. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104(9 Pt 1):715–717.

27. Westbrook, J.I., Coiera, E.W., Gosling, A.S. Do online information retrieval systems help experienced clinicians answer clinical questions? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(3):315–321.

28. Bennett, N.L., et al. Information-seeking behaviors and reflective practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(2):120–127.

29. Coumou, H.C., Meijman, F.J. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(1):55–60.

30. Pelz, J., Arendt, V., Kunze, J. Computer assisted diagnosis of malformation syndromes: An evaluation of three databases (LDDB, POSSUM, and SYNDROC). Am J Med Genet. 1996;63(1):257–267.

31. Computer-aided diagnosis software for neurological diseases. 2007. Available: http://www.flintbox.com/technology.asp?page=3087&lID=MCU (1 Dec 2009).

32. Sackett, D.L., et al. Evidence-based medicine. How to practice and teach EBM. Toronto: Churchill Livingsone, 2000. [261].

33. Greenhalgh, T. How to read a paper. The basics of evidence based medicine, 2nd edn. London: BMJ, 2001. [222].

34. Sackett, D.L., Haynes, R.B., Tugwell, P. Clinical epidemiology: A basic science for clinical medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, 1985. [370].

35. Altman, D.G. and J.M. Bland, Diagnostic tests 2: Predictive values. BMJ, 1994. 309(6947): p.102.

36. Newman, B.H., Waxman, D.A. Blood donation-related neurologic needle injury: Evaluation of 2 years’ worth of data from a large blood center. Transfusion. 1996;36(3):213–215.

37. Noseworthy, T.W., McGurran, J.J., Hadorn, D.C. Waiting for scheduled services in Canada: Development of priority-setting scoring systems. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9(1):23–31.

38. Catz, A., et al. Recovery of neurologic function following nontraumatic spinal cord lesions in Israel. Spine. 2004;29(20):2278–2282. [discussion 2283].

39. Fitzpatrick, R., Hopkins, A. Referrals to neurologists for headaches not due to structural disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44(12):1061–1067.

40. Koh, Y., Fatimah, B.M., Li, S.C. Therapy related hospital admission in patients on polypharmacy in Singapore: A pilot study. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(4):135–137.

41. Courtman, B.J., Stallings, S.B. Characterization of drug-related problems in elderly patients on admission to a medical ward. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1995;48(3):161–166.

1Recommended to the author by Dr Arthur Schwieger in 1985 and, to this day, remains one of the most powerful clinical tools available.

3Websites with instructions for searching the Internet for medical information are at the end of this chapter. Chapter 15, ‘Further reading, keeping up-to-date and retrieving information’, lists many relevant websites together with their URLs.

4It is important to inform the patient that you are looking up something that might help with their problem and not to spend too long or the patient will feel neglected. If you cannot find a ready answer, continue the search at a later time.

5The author was once told by a senior consultant ‘the spinal cord is unforgiving’.