CHAPTER 19 AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Affect refers to the external expression of emotions, whereas mood refers to the internal expression or feeling of emotions. Typically, affect and mood are congruent.1 However, in some conditions, they may be dissociated: Individuals with pseudobulbar palsy may have bursts of laughter or crying, which do not reflect how they feel at the time, whereas individuals with parkinsonism who do not have a depressed mood may appear depressed because of limited facial expressions. Mood has many manifestations, ranging from depression to euphoria.

Neuropsychiatric manifestations, such as changes in mood and affect, are very common in neurological conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease: apathy, agitation, depression, irritability, anxiety, psychosis; Parkinson’s disease: depression, anxiety, psychosis; frontotemporal dementia: disinhibition, apathy), cerebrovascular disease (depression, apathy, psychosis), epilepsy (depression, psychosis), and multiple sclerosis (depression, eutonia, irritability, anxiety).2 These manifestations have a significant effect on individuals’ quality of life and caregiver burden.

This chapter focuses on dysphoria (sadness) as the main feature of depression and elevated mood (exaggerated feeling of happiness) and expansive mood (expression of feelings without restraint and exaggerated sense of self-importance) as aspects of mania.1 We also discuss the personality change seen with apathy (lack of motivation). We provide information about prevalence, characteristics, course, and precipitating factors of mood changes in neurological conditions. The neuroanatomical localization of mood changes—commonly involving the basal ganglia and the frontal and anterior temporal regions—is reviewed. Finally, issues concerning treatment of mood changes in neurological conditions are discussed, and practical treatment algorithms are offered. A discussion of primary mood disorders and miscellaneous neurological conditions with mood changes, such as pseudobulbar palsy, Klüver-Bucy syndrome, ictal affect, hypothalamic lesions, and catastrophic reactions, is beyond the scope of this chapter.

DEPRESSION

Depression is a common feature of many neurological conditions, but it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. It can manifest as a symptom or as a syndrome complex such as a major depressive episode. Mood changes in depression consist of sadness and inability to experience pleasure (anhedonia), putatively mediated by the limbic system. They are often accompanied by feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness (mediated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), guilt, helplessness, and, in extreme situations, suicidal ideation. Affective changes in depression include changes in facial expressions (reduced or immobile expression [hypomimia], sad expression, or furrowed brow), crying, and avoidance of eye contact. Reduced interest in or reduced initiation of new activities is often present (mediated by the anterior cingulate cortex and related structures). Cognitive changes include reduced associations and executive and visuospatial dysfunction. Changes in verbal expression include increased speech latency, slow rate and reduced volume of speech, decreased spontaneous speech, and lack of emotional inflection (dysprosody). Neurovegetative changes mediated by the hypothalamus include appetite alterations, sleep disturbances, libido loss, and diurnal mood variations. Motor changes include slumped shoulders and head, decreased gestures, slowing of movements and gait, and catatonia (mediated by the basal ganglia).3,4

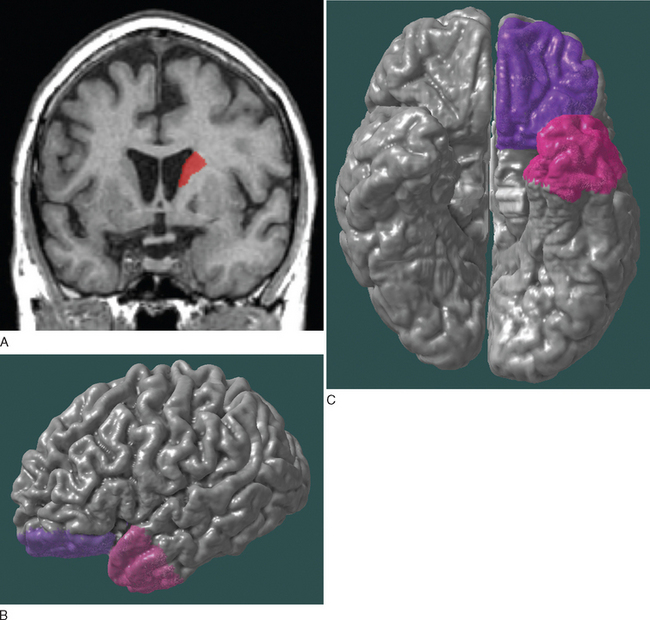

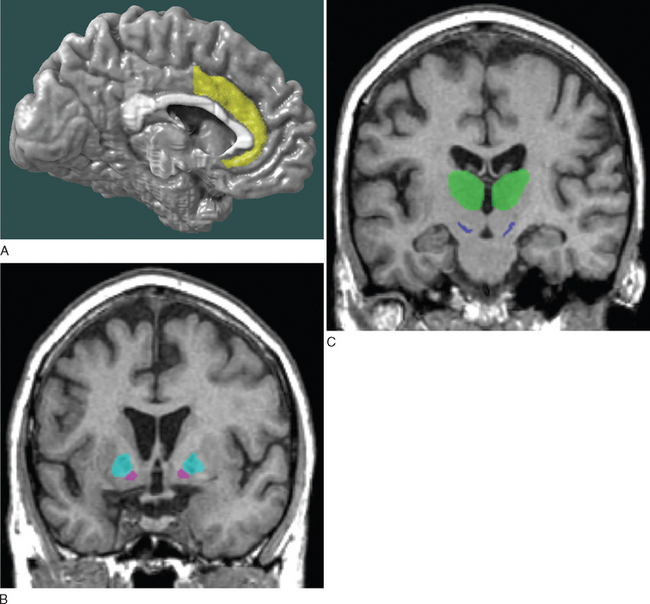

Depression in neurological conditions occurs most commonly with the involvement of the frontal region (orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices), temporal region (anterior temporal and paralimbic cortices), and basal ganglia (usually the caudate), mediated by the frontal-subcortical circuits. Lesions of the left hemisphere more commonly cause depression than do lesions of the right hemisphere (Fig. 19-1).2,5,6

Neurological conditions often can mask depression. Aphasic patients may not be able to voice their depressive feelings, whereas patients with dysprosody caused by basal ganglia or right hemisphere involvement may not be able to inflect their voice to convey their mood. In contrast, there are conditions that can imitate depression. Apathy, which is a common symptom in many neurological conditions, is commonly mistaken for depression. Patients with pseudobulbar palsy, parkinsonism, multiple sclerosis, and lesions causing emotional facial paresis may appear depressed without being so.3,7

The diagnosis of depression in neurological conditions is usually based on the criteria proposed for primary depression in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders1 and is often classified as major depression or minor depression (according to the criteria for dysthymic disorder). Alternatively, the presence of depression is assessed with specific rating scales such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory8 or the Geriatric Depression Scale.9

Depression can herald the onset or occur during the course of neurological conditions as a neurobiological component of those conditions or simply as a psychiatric comorbid condition. Cognitive changes seen in primary depression may sometimes imitate dementia, whereas depressive symptoms seen in dementia may sometimes imitate primary depression.3 The different presentations of depression in neurological conditions are described in the following sections and are summarized in Table 19-1. Table 19-2 lists neurological agents and psychotropic medications associated with depression.

TABLE 19-1 Neurological Conditions Manifesting with Depression

| Condition | Prevalence of Depression | Specific Features and Localization |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | MaD: 1%-23% | Milder depression and irritability greater functional deficits; depression heralds diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease; frontal and parietal involvement |

| MiD: 14%-34% | ||

| DS: 20%-55% | ||

| Parkinson’s disease | MaD: 8%-38% | Anxiety, greater motor fluctuations, greater cognitive impairment, akinetic-rigid variant; frontal (left) involvement |

| MiD: 10%-32% | ||

| DS: 34%-47% | ||

| Stroke | MaD: 8%-34% | More common in women than in men; depression associated with larger lesions; frontal, temporal, caudate involvement |

| Vascular dementia | MaD: 29%-45% | Increases with time, lower education level, and greater functional deficits |

| DS: 30%-34% | ||

| Epilepsy | MaD: 6%-30% | Increased suicide rate among patients with ictal and interictal forms; temporal (left), frontal involvement |

| Multiple sclerosis | MaD: 16% (lifetime, 50%) | Irritability, frustration, increased suicide rate; arcuate fasciculus (left) involvement |

| DS: 79%-85% | ||

| Traumatic brain injury115,116 | MaD: 17%-33% | Anxiety, aggressive behavior, lower education level, alcohol abuse, executive dysfunction; frontal (left) involvement |

| Huntington’s disease94,117 | MaD: 22% | Increased suicide rate; medial caudate, orbitofrontal involvement |

| Frontotemporal lobar degeneration107 | DS: 30% | Depression in semantic dementia is worse than in frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia |

| Wilson’s disease94 | MaD: 20% | Lenticular nuclei |

DS, general depressive symptoms; MaD, major depression; MiD, minor depression.

TABLE 19-2 Neurological Agents and Psychotropic Medications Associated with Depression3,78,82

| Antiparkinsonian drugs | Amantadine |

| Bromocriptine | |

| Levodopa | |

| Anticonvulsants | Phenobarbital |

| Primidone | |

| Tiagabine | |

| Vigabatrin | |

| Felbamate | |

| Topiramate | |

| Sedative-hypnotics | Benzodiazepines |

| Chloral hydrate | |

| Clomethiazole | |

| Clorazepate | |

| Neuroleptics | Butyrophenones |

| Phenothiazines | |

| Psychostimulants | Amphetamines |

| Diethylpropion | |

| Fenfluramine | |

| Phenmetrazine | |

| Miscellaneous | Acetazolamide |

| Azathioprine | |

| Baclofen | |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | |

| Corticosteroids | |

| Interferon-β1b/interferon-βa (possibly) |

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and produces cognitive impairment, functional deterioration, and behavioral changes. Among patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the prevalence of major depression has been reported as 1.1% to 23%10–15; that of minor depression, 13.9% to 34%10,13–15; and that of general depressive symptoms, 20.1% to 54.9%.16–20 As demonstrated, the reported rates of depression in Alzheimer’s disease have a wide range because of the different measures and criteria used. The criteria in the National Institute of Mental Health Provisional Diagnostic Criteria for Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease reflect the generally more mild depression in Alzheimer’s disease, requiring the presence of only 3 (of 11) depressive symptoms (rather than 5 as in primary major depression), including irritability and social withdrawal as symptoms, and not requiring the presence of symptoms to be nearly daily over 2 weeks.21,22

Depression in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with greater functional deficits, wandering behavior, agitation, anxiety, apathy, disinhibition, and irritability.14,18,23–25 Depressed Alzheimer’s disease patients often complain more about difficulties in thinking and concentration than about depressed mood and neurovegetative changes.26,27 Depressive symptoms tend to be episodic and recur frequently in Alzheimer’s disease.28,29 Frequency of mild depressive symptoms is correlated with severity of cognitive impairment15,30,31 but is not related to self-awareness of cognitive deficits.32 Depressive symptoms tend to occur early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease and may precede the diagnosis.15,33–35 Risk factors for developing depression in Alzheimer’s disease include female gender, lower education level, early-onset disease, family history of depression, and possibly premorbid history of depression.15,25,31,33,36,37

Depression in Alzheimer’s disease has been correlated mostly with frontal and parietal dysfunction. Functional imaging studies showed localization of associated lesions to the bilateral superior frontal and left anterior cingulate cortices38 or the parietal lobe,39 and quantified electroencephalographic recording pointed toward abnormalities of the parietal lobes.40 Pathological and neurochemical studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and depression demonstrated greater involvement of the locus ceruleus (noradrenergic system) and, to a lesser degree, the substantia nigra (dopaminergic system) and dorsal raphe nucleus (serotonergic system), with relative preservation of the nucleus basalis of Meynert (cholinergic system).41–44

Mild cognitive impairment is often a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among patients with mild cognitive impairment has been reported as 9.3% to 47%.16,17,45–47 One study reported that 85% of depressed patients with mild cognitive impairment went on to develop dementia, which again emphasizes the importance of depression in heralding the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.46

Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonian Syndromes

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disease (after Alzheimer’s disease) and has a range of motor manifestations, cognitive impairment, and behavioral disturbances. Among patients with Parkinson’s disease, the prevalence of major depression has been reported as 7.7% to 38%48–50; that of minor depression, 10% to 32%48,50; and that of general depressive symptoms, 34% to 47%.49,51–55 Depression in Parkinson’s disease is associated with less self-punitive ideation, more anxiety, dysautonomia, and greater motor fluctuations (“on-off” phenomenon). It is correlated with advanced stage of disease and greater cognitive impairment.49–51,54,56–59 Depression is more common in the akinetic-rigid Parkinson’s disease variant than the classic tremor-predominant type.48,51 Risk factors for depression in Parkinson’s disease include premorbid history of depression, greater functional deficits, lower cerebrospinal fluid levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, early-onset Parkinson’s disease, more left hemisphere involvement, and, possibly, female gender.50,51,57

Depression in Parkinson’s disease is associated with frontal lobe dysfunction, often of the left hemisphere, and is correlated with involvement of the dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic systems.50,51,60 Neuropsychological studies show a relationship with disruption of frontal-lobe related tasks.61 Functional imaging studies show a localization of depression-related dysfunction in the bilateral medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices62 or caudate and inferior orbitofrontal cortex.63

Depression has been reported in other parkinsonian syndromes. Among patients with dementia with Lewy bodies, the prevalence of major depression has been reported as 19% to 33.3%12,64 and that of general depressive symptoms, 47.5%.12 Among patients with progressive supranuclear palsy, the prevalence of general depressive symptoms has been reported as 18% to 25%,53,65 whereas that among patients with corticobasal degeneration has been reported as 73%.65

Cerebrovascular Disease

Depression in cerebrovascular disease has been described in the context of vascular depression, discrete strokes, and vascular dementia. Patients with vascular depression have clinical or imaging evidence of cerebrovascular disease, as well as vascular risk factors.66 In comparison with patients with primary depression, patients with vascular depression are older at onset of mood changes and have greater functional disability and cognitive impairment (mostly in verbal fluency and naming), greater psychomotor retardation, greater anhedonia, less agitation, lesser feelings of guilt, less insight, and less family history of depression.66,67 Vascular depression is associated with single or multiple lesions that disrupt the striatopallidothalamocortical (prefrontal) pathways.66,68

The prevalence of major depression among patients who have suffered strokes has been reported as 8.3% to 33.6%.69–71 Poststroke major depression is more common in women (23.6%), in whom it is associated with more left hemisphere lesions and a history of psychiatric disorder and cognitive impairment, whereas in men (12.3%), it is associated with greater functional deficits.72 Depression has been shown to be more common with larger lesion volumes.71 Lesions in the frontal and temporal lobes, basal ganglia (especially the head of the caudate), and ventral brainstem circuitry are associated with depression.70,73 However, there is a tendency for depression after the acute poststroke period to be related to lesions of the left frontal region, whereas depression in the chronic poststroke period is associated with lesions of the right posterior region.4,74

Vascular dementia is the second most common dementia and is associated with executive dysfunction, motor symptoms, and significant behavioral changes. Among patients with vascular dementia, the prevalence of major depression has been reported as 29% to 45%,64,75 and that of general depressive symptoms, 29.7% to 34.2%.19,75,76 Depressive symptoms in vascular dementia tend to increase with time and are related to lower education level and greater functional deficits.25,76

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is common and is associated with significant behavioral disturbances. The prevalence of major depression among patients with epilepsy has been reported as 6% to 30%.77,78 Depression in epilepsy is associated with decreased quality of life and increased suicide rate (5 to 10 times higher than in the general population).77–79 Ictal and interictal forms of depression have been reported in epilepsy: The “interictal dysphoric disorder” resembles dysthymia and consists of depressed mood, low energy, pain, insomnia, irritability, euphoria, fear, and anxiety, whereas ictal depression usually occurs as an “aura” for a seizure and consists of guilt, anhedonia, and suicidal ideation.77 Depression is more common in patients with temporal (often left) and frontal seizure foci, and the hippocampus and amygdala appear to play a role as well.77,80,81

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease with widespread physical, cognitive, and behavioral changes. Among patients with multiple sclerosis, the prevalence of major depression has been reported as 15.7% (lifetime prevalence, 50%)82,83 and that of general depressive symptoms, 79% to 85%.84,85 Depression in multiple sclerosis is associated with discouragement, irritability, frustration, higher rate of suicide (seven times higher than in the general population), and greater volume of lesions and cerebral atrophy.82 Depression in multiple sclerosis has been associated with lesions of the arcuate fasciculus, more so on the left.86

Treatment of Depression

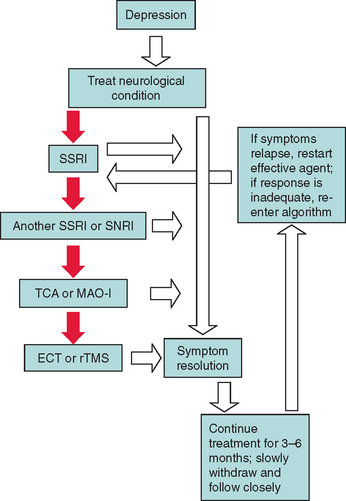

Few controlled clinical trials have addressed depression in neurological conditions, and no medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for this indication. For most conditions, clinicians have used medications studied in primary depression, which are often not as well tolerated and not as effective in neurological conditions. Therefore, a good adage is “Start low and go slow.” Direct treatment of the neurological condition may be helpful in treating the secondary depression. In dementias with cholinergic deficits, the use of cholinesterase inhibitors has proved helpful in the treatment of neuropsychiatric manifestations,87 as well as in depression specifically.88 There is also some evidence that memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist approved by the FDA for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, may have similar effects.89 In Parkinson’s disease, selegiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, and D3 receptor agonists, such as pramipexole and ropinirole, have shown antidepressant effects.90,91

The first-line antidepressants in most neurological conditions are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, because of their tolerability, safety, and apparent efficacy (especially sertraline and citalopram in Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy). Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as venlafaxine and mirtazapine, appear to be good alternative first-line agents because of their tolerability, but they are newer agents and have not been studied adequately. Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors have been shown to be effective but often are not tolerated as well, especially by elderly patients, and therefore are considered second-line agents. If the patient’s depression resolves, the antidepressant should be continued for 3 to 6 months and then gradually tapered, while the patient is monitored closely for recurrence of depression.4,78,92

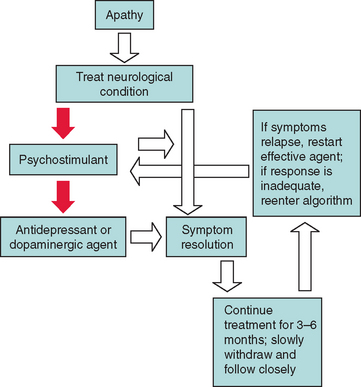

In patients with severe depression that is refractory to medical treatment, electroconvulsive therapy and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be effective (especially in Parkinson’s disease).90 Electroconvulsive therapy should not be performed in patients with elevated intracranial pressure, headache, or focal neurological deficits. Figure 19-2 provides an algorithm for the treatment of depression in neurological conditions.

MANIA

Mania has been reported in multiple neurological conditions and as a consequence of medication use. It consists of elevated or expansive mood, irritability (often associated with aggressiveness), accelerated and/or disorganized thought or speech, distractibility, poor judgment, psychomotor agitation, expansive gestures and facial expressions, and neurovegetative changes (decreased need for sleep, hypersexuality, and increased energy). Mania may be accompanied by moodcongruent hallucinations or delusions. Hypomania is similar to mania but milder and is not accompanied by psychosis. Many patients with secondary mania caused by a focal lesion have a family history of psychiatric morbidity. Certain neurological conditions, such as pseudobulbar palsy, may imitate mania.1,3

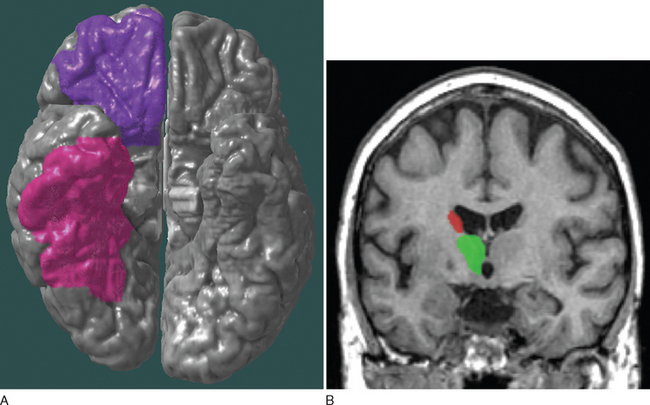

Mania in neurological conditions has been correlated with lesions of the frontal region (especially the orbitofrontal area), basal ganglia (especially the inferior caudate), thalamus, and inferior temporal region, usually lateralized to the right, which possibly reflects overactivity of the paleocortical limbic division (Fig. 19-3).2,5 The different manifestations of mania in neurological conditions are described and summarized in Table 19-3. Table 19-4 lists neurological agents and psychotropic medications associated with mania.

TABLE 19-3 Neurological Conditions Manifesting with Mania and Elevated Mood

| Condition | Prevalence of Mania | Specific Features and Localization |

|---|---|---|

| Stroke | Rare | Hyperkinetic movement disorders; right thalamus (frontal, basal ganglia) involvement |

| Huntington’s disease | 5% (hypomania, 10%) | Euphoria or irritability, grandiosity, overactivity, impulsiveness, insomnia |

| Traumatic brain injury | 9% | Irritability, aggressiveness; brief duration; family history; post-traumatic seizures; right thalamus, caudate, orbitofrontal, and inferior temporal involvement |

| Human immunodeficiency virus118 | 8% | Late-onset presentation usually without family history and with dementia |

| Multiple sclerosis82 | Twice more common than in general population | Eutonia; possible genetic predisposition in women |

| Alzheimer’s disease119 | 2.2% | May precede cognitive decline |

| Miscellaneous98 | Frontotemporal dementia, neurosyphilis, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, tumors (hypothalamic involvement) |

TABLE 19-4 Neurological Agents and Psychotropic Medications Associated with Mania and Elevated Mood

| Antiparkinsonian drugs | Amantadine |

| Bromocriptine | |

| Levodopa | |

| Lisuride | |

| Piribedil | |

| Procyclidine | |

| Selegiline | |

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine |

| Phenytoin | |

| Barbiturates | |

| Ethosuximide | |

| Clonazepam | |

| Phenacemide | |

| Sedative-hypnotics | Alprazolam |

| Triazolam | |

| Buspirone | |

| Meprobamate | |

| Antidepressants | Bupropion |

| SSRIs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline) | |

| TCAs (phenelzine) | |

| MAOIs (clomipramine imipramine, desipramine, amitriptyline) | |

| Mirtazapine | |

| Nefazodone | |

| Trazodone | |

| Antipsychotics | Olanzapine |

| Risperidone | |

| Miscellaneous | Baclofen |

| Psychostimulants | |

| Corticosteroids |

MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.3,120,121

Cerebrovascular Disease

Mania has been described in patients with focal strokes. It is often associated with hyperkinetic movement disorders (hemiballismus, chorea, postural tremor, hemidystonia).93 Lesions are usually right-sided and involve subcortical and midline structures (especially the thalamus), damaging the frontal-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits.93

Extrapyramidal Disorders

Although not as common as depression, mania is seen in patients with Huntington’s disease. Among such patients, the prevalence of mania and hypomania has been reported as 4.8% and 10%, respectively. Mania in Huntington’s disease consists of euphoria or irritability, grandiosity, overactivity, impulsiveness, and decreased need for sleep.94

Patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with dopaminergic agents or surgically (deep brain stimulation, pallidotomy, or thalamotomy) may develop mania. Among patients with medically treated Parkinson’s disease, the prevalence of mania has been reported as 1% (euphoria, 10%).3,95

Traumatic Brain Injury

Mania has been observed after traumatic brain injury. The prevalence of such mania has been reported as 9%. In traumatic brain injury, mania is associated with irritability and aggressiveness and is usually short-lasting (about 2 months). Risk factors for developing mania in TBI include family history of mood disorders, post-traumatic seizures, and premorbid diencephalic and frontal subcortical atrophy. Mania in traumatic brain injury is related to lesions localized in the right hemisphere, particularly the thalamus, caudate, and orbitofrontal and inferior temporal regions.96,97

Treatment of Mania

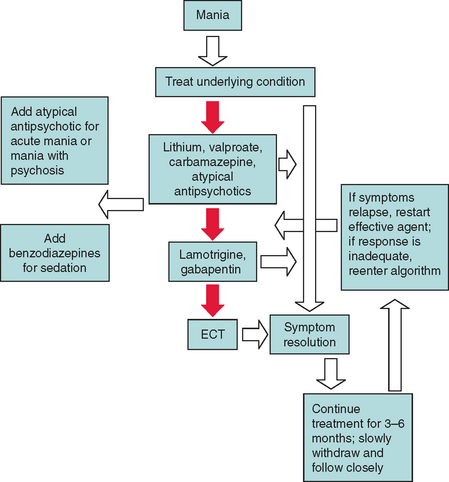

Essentially no clinical trials have addressed mania in neurological conditions, and no medications have been approved by the FDA for this indication. For most conditions, clinicians have used medications studied in primary bipolar illness. However, before mood stabilizer treatment is initiated, the underlying condition should be treated or, in the case of medication-induced mania, the offending agent discontinued.98

The commonly used mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, and atypical antipsychotics. Patients with mania in some neurological conditions, such as Huntington’s disease or human immunodeficiency virus infection, do not respond as well to lithium and are more vulnerable to its toxic effects. Lamotrigine and gabapentin are newer anticonvulsants that may have a role as mood stabilizers as well. If the patient’s mania resolves, the mood stabilizer should be continued for 3 to 6 months and then gradually tapered, while the patient is monitored closely for recurrence of mania. In the acute stages of mania or in mania with moodcongruent delusions and hallucinations, an atypical antipsychotic may be added. Atypical antipsychotics may be the best choice for management of mania in some patients. If sedation is desired, a benzodiazepine may be added. If patients are resistant to mood stabilizers, electroconvulsive therapy may be considered.3,82,94,99 Figure 19-4 provides an algorithm for the treatment of mania in neurological conditions.

APATHY

Apathy is a common neuropsychiatric symptom in neurological conditions, especially in neurodegenerative diseases. It consists of loss of interest, emotions, or motivation, and in extreme situations, patients become akinetic and mute. Apathy may resemble depression and may coexist with a mood disorder, but it has been shown to be a separate entity. The decreased motivation seen in apathy (mediated by the anterior cingulate cortex) is associated with lack of concern (mediated by the parietal lobe), impaired cognition (mediated by the neocortex), placidity and impaired emotional memory (mediated by the medial temporal lobe), inattention (mediated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), decreased experience of emotion (mediated by the limbic system), and decreased perception and expression of emotion (mediated by the right hemisphere).3–5,100,101

As just mentioned, apathy in neurological conditions has been related to lesions localized to the anterior cingulate gyrus, nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and thalamus, which make up the anterior cingulate-subcortical circuit, responsible for mediating motivation (Fig. 19-5).2,4–6 The different manifestations of apathy in neurological conditions are listed in Table 19-5.

| Condition | Prevalence of Apathy | Specific Features and Localization |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | 29%-70% | Associated with executive dysfunction and severity of cognitive impairment; distinct from depression; apathy heralds diagnosis of Alzhermer’s disease; anterior cingulate involvement |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 68%-90% | Occurs early in the course of disease, more common in frontal variant |

| Parkinson’s disease | 17%-20% | Occurs in advanced stage of disease; greater cognitive impairment and executive dysfunction |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | 84%-90% | Orbitofrontal and medial frontal circuit involvement |

| Stroke | 57% | Decreased heart rate reactivity to mental stress; right hemisphere lesions |

| Traumatic brain injury110 | 46% | Right hemisphere lesions |

| Huntington’s disease94 | 48% | Disregard for appearance and personal hygiene |

| Multiple sclerosis85 | 20% | Variable correlations with imaging changes |

Alzheimer’s Disease

Apathy is the most common neuropsychiatric symptom in Alzheimer’s disease. Among patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the prevalence of apathy has been reported as 28.5% to 70%.4,16,17,19,102 It has been shown to be associated with executive dysfunction and severity of cognitive impairment but remaining distinct from depression.30,102 Apathy often heralds the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or becomes apparent early in its course.33,103 Apathy has been reported among patients with mild cognitive impairment with a prevalence of 11.1% to 39%.16,17,47

Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease is associated in most cases with lesions of the anterior cingulate gyrus. Functional imaging studies showed localization to the anterior cingulate bilaterally104 or the prefrontal and anterior temporal regions.105 One pathological study showed increased pathological burden in the anterior cingulate gyrus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and apathy.106

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia is a degenerative dementia in which prominent behavioral changes manifest early in its course. The prevalence of apathy among patients with frontotemporal dementia has been reported as 68% to 90%.4,107,108 Apathy occurs early in the course of frontotemporal dementia, is associated with loss of emotions and loss of interest, and is more common in the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia.107,108

Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonian Syndromes

Apathy has been reported in the various parkinsonian syndromes. The prevalence of apathy among patients with Parkinson’s disease has been reported as 16.5% to 20%.4,53,54 Apathy in Parkinson’s disease is correlated with advanced stage of disease, greater cognitive impairment, and executive dysfunction.54,109

The prevalence of apathy among patients with progressive supranuclear palsy has been reported as 84% to 90%,4,53 and apathy has been associated with lesions of the orbitofrontal and medial frontal circuits.53 Among patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies and corticobasal degeneration, the prevalence of apathy has been reported as 90% and 40%, respectively.4

Cerebrovascular Disease

Apathy in cerebrovascular disease has been described in the context of stroke and vascular dementia. The prevalence of apathy among stroke patients has been reported as 56.7% and has been associated with predominantly right hemisphere lesions and decreased heart rate reactivity to mental stress.110 The prevalence of apathy among patients with vascular dementia has been reported as 22.6% to 47%.19,108

Treatment of Apathy

No clinical trials have addressed apathy in neurological conditions, and no medications have been approved by the FDA for this indication. Direct treatment of the neurological condition may be helpful in treating the associated apathy. The use of cholinesterase inhibitors in dementias with cholinergic deficits (Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies) has been shown to improve neuropsychiatric symptoms and apathy (and visual hallucinations) in particular.87,88,111,112

Psychostimulants and related agents have been commonly used to treat severe apathy in neurological conditions. These drugs, which include methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, atomoxetine, and modafinil, have been used successfully in patients with dementia and stroke.113,114 Some antidepressants with activating properties (fluoxetine and desipramine) and dopaminergeric agents (amantadine and bromocriptine) have been used successfully in patients with Huntington’s disease and akinetic mutism.2,94 If treatment is successful, the medication should be continued for 3 to 6 months and then gradually tapered, while the patient is monitored closely for recurrence of apathy (this does not apply to cholinesterase inhibitors). Figure 19-6 provides an algorithm for the treatment of apathy in neurological conditions.

Aarsland D, Litvan I, Larsen JP. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:42-49.

Cummings JL. Principles of neuropsychiatry: towards a neuropsychiatric epistemology. Neurocase. 1999;5:181-188.

Cummings JL. Cognitive and behavioral heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease: seeking the neurobiological basis. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:845-861.

Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatry of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. London: Martin Dunitz, 2003.

Cummings JL, Mega MS. Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

2 Cummings JL. Principles of neuropsychiatry: towards a neuropsychiatric epistemology. Neurocase. 1999;5:181-188.

3 Cummings JL, Mega MS. Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

4 Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatry of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. London: Martin Dunitz, 2003.

5 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Salloway S, et al. The limbic system: an anatomic, phylogenetic, and clinical perspective. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:315-330.

6 Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical circuits and human behavior. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:873-880.

7 Hopf HC, Muller-Forell W, Hopf NJ. Localization of emotional and volitional facial paresis. Neurology. 1992;42:1918-1923.

8 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308-2314.

9 Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37-49.

10 Gilley DW, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:P75-P83.

11 Weiner MF, Doody RS, Sairam R, et al. Prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder in Alzheimer’s disease: findings from two databases. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;13:8-12.

12 Ballard C, Holmes C, McKeith I, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective clinical and neuropathological comparative study with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1039-1045.

13 Starkstein SE, Chemerinski E, Sabe L, et al. Prospective longitudinal study of depression and anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:47-52.

14 Lyketsos CG, Steele C, Baker L, et al. Major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence and impact. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:556-561.

15 Migliorelli R, Teson A, Sabe L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of dysthymia and major depression among patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:37-44.

16 Geda YE, Smith GE, Knopman DS, et al. De novo genesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:51-60.

17 Hwang TJ, Masterman DL, Ortiz F, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with characteristic neuropsychiatric symptoms. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18:17-21.

18 Cummings JL. The impact of depressive symptoms on patients with Alzheimer disease [Comment]. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17:61-62.

19 Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, et al. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:708-714.

20 Frisoni GB, Rozzini L, Gozzetti A, et al. Behavioral syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease: description and correlates. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:130-138.

21 Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:125-128.

22 Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:129-141. [Erratum in Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:264].

23 Espiritu DA, Rashid H, Mast BT, et al. Depression, cognitive impairment and function in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1098-1103.

24 Fitz AG, Teri L. Depression, cognition, and functional ability in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:186-191.

25 Hargrave R, Reed B, Mungas D. Depressive syndromes and functional disability in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2000;13:72-77.

26 Heun R, Kockler M, Ptok U. Lifetime symptoms of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18:63-69.

27 Devanand DP, Jacobs DM, Tang MX, et al. The course of psychopathologic features in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:257-263.

28 Marin DB, Green CR, Schmeidler J, et al. Noncognitive disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease: frequency, longitudinal course, and relationship to cognitive symptoms. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1331-1338.

29 Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, et al. Longitudinal assessment of symptoms of depression, agitation, and psychosis in 181 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1438-1443.

30 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130-135.

31 Devanand DP, Sano M, Tang MX, et al. Depressed mood and the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly living in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:175-182.

32 Cummings JL, Ross W, Absher J, et al. Depressive symptoms in Alzheimer disease: assessment and determinants. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9:87-93.

33 Jost BC, Grossberg GT. The evolution of psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a natural history study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1078-1081.

34 Berger AK, Fratiglioni L, Forsell Y, et al. The occurrence of depressive symptoms in the preclinical phase of AD: a population-based study. Neurology. 1999;53:1998-2002.

35 Chen P, Ganguli M, Mulsant BH, et al. The temporal relationship between depressive symptoms and dementia: a community-based prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:261-266.

36 Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, et al. Association between premorbid history of depression and current depression in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12:72-75.

37 Strauss ME, Ogrocki PK. Confirmation of an association between family history of affective disorder and the depressive syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1340-1342.

38 Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, et al. Frontal lobe hypometabolism and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;50:380-383.

39 Sultzer DL, Mahler ME, Mandelkern MA, et al. The relationship between psychiatric symptoms and regional cortical metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:476-484.

40 Pozzi D, Golimstock A, Petracchi M, et al. Quantified electroencephalographic changes in depressed patients with and without dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:677-683.

41 Zubenko GS. Clinicopathologic and neurochemical correlates of major depression and psychosis in primary dementia.Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(Suppl 3):219-223. discussion, Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(Suppl 3):269-272.

42 Forstl H, Burns A, Luthert P, et al. Clinical and neuropathological correlates of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Med. 1992;22:877-884.

43 Zubenko GS, Moossy J, Kopp U. Neurochemical correlates of major depression in primary dementia. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:209-214.

44 Zubenko GS, Moossy J. Major depression in primary dementia. Clinical and neuropathologic correlates. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:1182-1186.

45 Feldman H, Scheltens P, Scarpini E, et al. Behavioral symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2004;62:1199-1201.

46 Modrego PJ, Ferrandez J. Depression in patients with mild cognitive impairment increases the risk of developing dementia of Alzheimer type: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1290-1293.

47 Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475-1483.

48 Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, et al. Depression in classic versus akinetic-rigid Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1998;13:29-33.

49 Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, et al. The occurrence of depression in Parkinson’s disease. A community-based study. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:175-179.

50 Cole SA, Woodard JL, Juncos JL, et al. Depression and disability in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:20-25.

51 Cummings JL. Depression and Parkinson’s disease: a review. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:443-454.

52 Shulman LM, Taback RL, Rabinstein AA, et al. Non-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8:193-197.

53 Aarsland D, Litvan I, Larsen JP. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:42-49.

54 Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Lim NG, et al. Range of neuropsychiatric disturbances in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:492-496.

55 Dooneief G, Mirabello E, Bell K, et al. An estimate of the incidence of depression in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:305-307.

56 Norman S, Troster AI, Fields JA, et al. Effects of depression and Parkinson’s disease on cognitive functioning. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14:31-36.

57 Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, et al. Risk factors for depression in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:625-630.

58 Berrios GE, Campbell C, Politynska BE. Autonomic failure, depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:789-792.

59 Richard IH, Justus AW, Kurlan R. Relationship between mood and motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:35-41.

60 Mayeux R, Stern Y, Cote L, et al. Altered serotonin metabolism in depressed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:642-646.

61 Kuzis G, Sabe L, Tiberti C, et al. Cognitive functions in major depression and Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:982-986.

62 Ring HA, Bench CJ, Trimble MR, et al. Depression in Parkinson’s disease. A positron emission study. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:333-339.

63 Mayberg HS, Starkstein SE, Sadzot B, et al. Selective hypometabolism in the inferior frontal lobe in depressed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:57-64.

64 Ballard C, Bannister C, Solis M, et al. The prevalence, associations and symptoms of depression amongst dementia sufferers. J Affect Disord. 1996;36:135-144.

65 Litvan I, Cummings JL, Mega M. Neuropsychiatric features of corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:717-721.

66 Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:562-565.

67 Krishnan KR, Hays JC, Blazer DG. MRI-defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:497-501.

68 Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. “Vascular depression” hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:915-922.

69 Toso V, Gandolfo C, Paolucci S, et al. Poststroke depression: research methodology of a large multicentre observational study (DESTRO). Neurol Sci. 2004;25:138-144.

70 Kim JS, Choi-Kwon S. Poststroke depression and emotional incontinence: correlation with lesion location. Neurology. 2000;54:1805-1810.

71 Sharpe M, Hawton K, House A, et al. Mood disorders in long-term survivors of stroke: associations with brain lesion location and volume. Psychol Med. 1990;20:815-828.

72 Paradiso S, Robinson RG. Gender differences in poststroke depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:41-47.

73 Starkstein SE, Robinson RG, Berthier ML, et al. Differential mood changes following basal ganglia vs thalamic lesions. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:725-730.

74 Shimoda K, Robinson RG. The relationship between poststroke depression and lesion location in long-term follow-up. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:187-192.

75 Reichman WE, Coyne AC. Depressive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995;8:96-99.

76 Li YS, Meyer JS, Thornby J. Longitudinal follow-up of depressive symptoms among normal versus cognitively impaired elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:718-727.

77 Kanner AM. Depression in epilepsy: a frequently neglected multifaceted disorder. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(Suppl 4):11-19.

78 Kanner AM. Depression in epilepsy: prevalence, clinical semiology, pathogenic mechanisms, and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:388-398.

79 Johnson EK, Jones JE, Seidenberg M, et al. The relative impact of anxiety, depression, and clinical seizure features on health-related quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:544-550.

80 Hecimovic H, Goldstein JD, Sheline YI, et al. Mechanisms of depression in epilepsy from a clinical perspective. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(Suppl 3):S25-S30.

81 Victoroff JI, Benson F, Grafton ST, et al. Depression in complex partial seizures. Electroencephalography and cerebral metabolic correlates. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:155-163.

82 Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:157-163.

83 Patten SB, Beck CA, Williams JV, et al. Major depression in multiple sclerosis: a population-based perspective. Neurology. 2003;61:1524-1527.

84 Zephir H, De Seze J, Stojkovic T, et al. Multiple sclerosis and depression: influence of interferon beta therapy. Mult Scler. 2003;9:284-288.

85 Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, et al. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;11:51-57.

86 Pujol J, Bello J, Deus J, et al. Lesions in the left arcuate fasciculus region and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1997;49:1105-1110.

87 Wynn ZJ, Cummings JL. Cholinesterase inhibitor therapies and neuropsychiatric manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:100-108.

88 Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, et alDonepezil MSAD Study Investigators Group. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:613-620. [Erratum in Neurology 2001; 57:2153].

89 Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, et alMemantine Study Group. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:317-324.

90 Tom T, Cummings JL. Depression in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacological characteristics and treatment. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:55-74.

91 Cummings JL. D-3 receptor agonists: combined action neurologic and neuropsychiatric agents [Comment]. J Neurol Sci. 1999;163:2-3.

92 Lyketsos CG, Olin J. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: overview and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:243-252.

93 Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J, Gironell A, et al. Poststroke bipolar affective disorder: clinical subtypes, concurrent movement disorders, and anatomical correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:160-167.

94 Rosenblatt A, Leroi I. Neuropsychiatry of Huntington’s disease and other basal ganglia disorders. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:24-30.

95 Cummings JL. Behavioral complications of drug treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:708-716.

96 Wright MT, Cummings JL, Mendez MF, et al. Bipolar syndromes following brain trauma. Neurocase. 1997;3:111-118.

97 Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Starkstein SE, et al. Secondary mania following traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:916-921.

98 Mendez MF. Mania in neurologic disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2:440-445.

99 Dunn RT, Frye MS, Kimbrell TA, et al. The efficacy and use of anticonvulsants in mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:215-235.

100 Marin RS. Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:243-254.

101 Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, et al. Apathy is not depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:314-319.

102 McPherson S, Fairbanks L, Tiken S, et al. Apathy and executive function in Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:373-381.

103 Cummings JL. Cognitive and behavioral heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease: seeking the neurobiological basis. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:845-861.

104 Migneco O, Benoit M, Koulibaly PM, et al. Perfusion brain SPECT and statistical parametric mapping analysis indicate that apathy is a cingulate syndrome: a study in Alzheimer’s disease and nondemented patients. Neuroimage. 2001;13:896-902.

105 Craig AH, Cummings JL, Fairbanks L, et al. Cerebral blood flow correlates of apathy in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:1116-1120.

106 Tekin S, Mega MS, Masterman DM, et al. Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:355-361.

107 Bozeat S, Gregory CA, Ralph MA, et al. Which neuropsychiatric and behavioural features distinguish frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:178-186.

108 Bathgate D, Snowden JS, Varma A, et al. Behaviour in frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:367-378.

109 Pluck GC, Brown RG. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:636-642.

110 Andersson S, Krogstad JM, Finset A. Apathy and depressed mood in acquired brain damage: relationship to lesion localization and psychophysiological reactivity. Psychol Med. 1999;29:447-456.

111 Erkinjuntti T, Kurz A, Gauthier S, et al. Efficacy of galanta-mine in probable vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease combined with cerebrovascular disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1283-1290.

112 McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356:2031-2036.

113 Galynker I, Ieronimo C, Miner C, et al. Methylphenidate treatment of negative symptoms in patients with dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:231-239.

114 Watanabe MD, Martin EM, DeLeon OA, et al. Successful methylphenidate treatment of apathy after subcortical infarcts. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:502-504.

115 Dikmen SS, Bombardier CH, Machamer JE, et al. Natural history of depression in traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1457-1464.

116 Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Moser D, et al. Major depression following traumatic brain injury. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:42-50.

117 Mayberg HS, Starkstein SE, Peyser CE, et al. Paralimbic frontal lobe hypometabolism in depression associated with Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:1791-1797.

118 Lyketsos CG, Hanson AL, Fishman M, et al. Manic syndrome early and late in the course of HIV. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:326-327.

119 Lyketsos CG, Corazzini K, Steele C. Mania in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:350-352.

120 Aubry JM, Simon AE, Bertschy G. Possible induction of mania and hypomania by olanzapine or risperidone: a critical review of reported cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:649-655.

121 Sultzer Dl, Cummings JL. Drug-induced mania—causative agents, clinical characteristics and management: a restrospective analysis of the literature. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1989;4:127-143.