CHAPTER 18 Aesthetic facial microsurgery

History

Although microsurgery has traditionally served a reconstructive role in plastic surgery, it has evolved into an important modality for difficult aesthetic problems. The goals of correcting facial asymmetry center on restoring the underlying skeletal framework and recruiting soft tissue bulk. Prior to microsurgery, patients would undergo correction of the skeletal support with bone or cartilage grafts followed by soft tissue enhancement with local tissue recruitment, dermal fat grafts, synthetic or autologous fillers in a single or staged procedure. The use of microvascular free flaps allows a large volume of soft tissue with an osseous component (if necessary) to be reliably transferred to the face in a single stage.

Physical evaluation

• A thorough history is taken to ensure that any disease process, previous trauma or surgical scars are stable.

• Accurately assess the distribution and extent of the soft tissue deficiencies in three-dimensions with the patient in the upright position.

• Make a two-dimensional template of the deficiencies marking areas that require both increased augmentation and areas where the flap will be tapered.

• Accurately assess any deficiencies in the facial skeleton.

• Assess the superficial temporal vessels as potential recipient vessels for the free flap.

• Assess the parascapular region to ensure primary closure of the donor defect or consider preoperative tissue expansion.

Anatomy

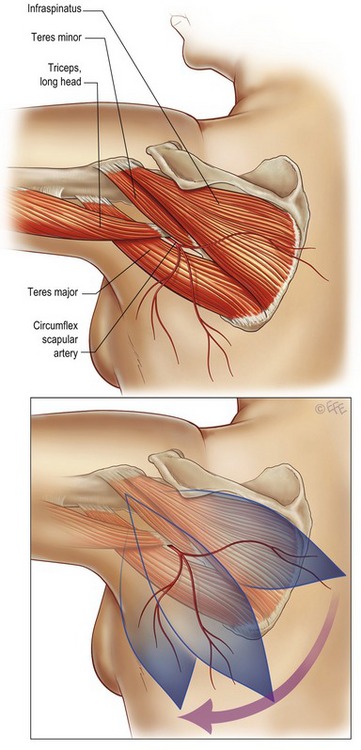

The parascapular flap is a fasciocutaneous flap based on the circumflex scapular vessels off of the subscapular system. The circumflex scapular vessels pass through the triangular space bound by the teres minor muscle superiorly, the teres major inferiorly, and the long head of the triceps laterally (Fig. 18.1A). After passing through the triangular space, the artery gives off a branch that supplies the lateral border of the scapula allowing an osseous component to the flap. The circumflex scapular artery divides into two terminal branches, a horizontal and descending cutaneous branch. There are two accompanying veins that travel with the artery. Both or just the larger vein can be used to revascularize the flap.

The cutaneous skin paddle can be either vertically or obliquely designed depending on the degree of laxity of the skin, as well as, the aesthetic desires of the patient (Fig. 18.1B). The borders of the skin paddle for traditional parascapular flaps are the triangular space superiorly, the vertebral column medially, the axilla laterally, and inferiorly to the level approximately halfway between the inferior angle of the scapula and the posterior superior iliac spine. To ensure primary closure of the donor site, the skin paddle is often limited to a width of 10 cm. We have used extended inframammary flaps for the correction of facial contour problems because the resulting donor site scar is more favorably oriented. The only requisite for any of these flaps is that the circumflex scapular vessels are contained within the base of the flap.

The superficial temporal vessels are the most common recipient vessels for the vascular anastomosis. The superficial temporal artery is the terminal branch of the external carotid artery whose origin lies within the parotid gland. It lies approximately 1 cm anterior to the tragus. Above the level of the zygomatic arch, the superficial temporal artery lies just deep to the superficial temporal fascia. The vessels are easily exposed through a preauricular incision, the same incision used to expose the recipient site in the face. It is sometimes necessary to follow the vessels deep into the parotid if the vessels are not adequate superiorly. If the superficial temporal vessels are not adequate, there may be the need to extend the preauricular incision into the neck or better to make an additional transverse incision in the neck.

Technical steps

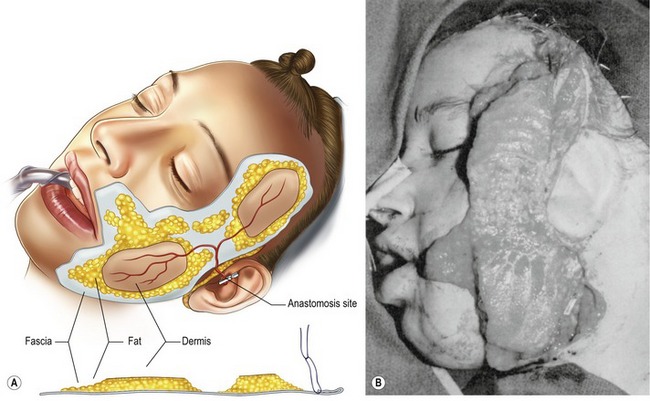

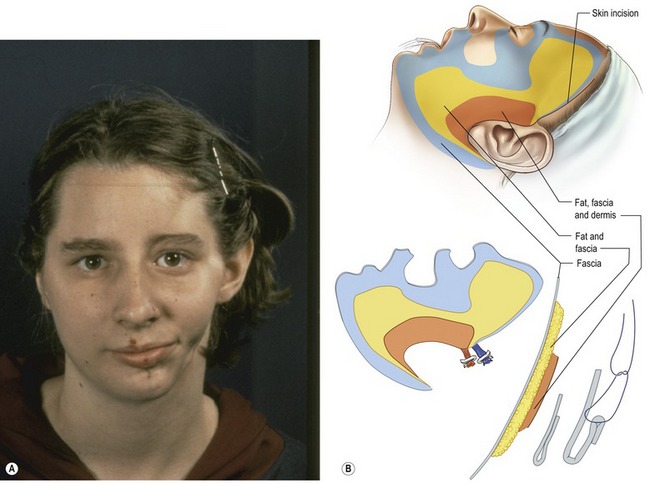

The areas of deficiency are marked with the patient in the upright position. Care is taken to specifically mark areas where increased augmentation is necessary and where the flap requires tapering (Fig. 18.2). The maximal width of the soft tissue deficiency in the face will correspond to the width of the skin paddle of the flap.

Fig. 18.2 A, Preoperative view of an 18-year-old woman with left-sided hemifacial atrophy. B, Representative diagram demonstrating the extent of the soft tissue deficiency and the proposed composite tissue required for reconstruction. C, Preoperative markings demonstrating the soft tissue defects and areas for augmentation. D, The parascapular flap anastomosed to the superficial temporal vessels prior to flap inset. The flap can be contoured by either removing flap tissue or by folding the fascial tissue upon itself.

B–D, Reproduced with permission from Longaker MT, Siebert JW. Microvascular free-flap correction of severe hemifacial atrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96(4):800–809.

Harvesting of the flap occurs in a caudad to cephalad direction. After the skin is incised, dissection occurs down to the deep fascia. Extensions of the dorsal thoracic fascia are dissected as needed to precisely contour the flap. Subfascial dissection begins distally and carefully proceeds in a retrograde fashion. The pedicle on the deep surface is identified and dissection is carried back to the takeoff of the thoracodorsal pedicle. The circumflex vessels are individually isolated and ligated. Hemostasis is achieved and the donor site is closed in layers over closed suction drains.

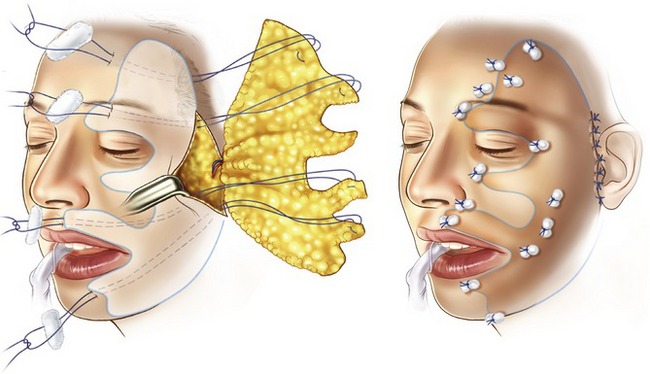

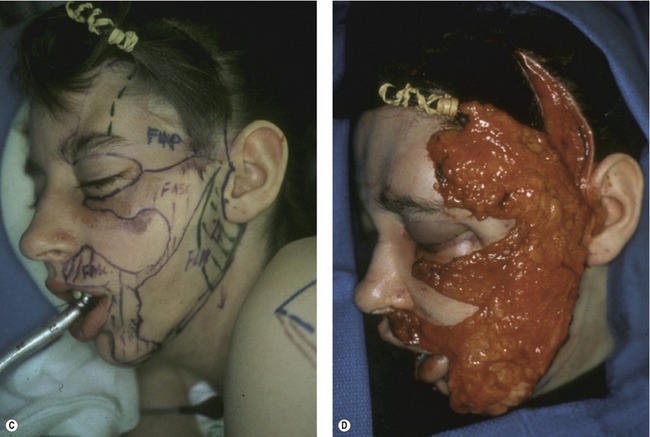

The flap is brought to the face and draped in the desired orientation. The circumflex parascapular vessels are anastomosed to the superficial temporal vessels. The skin paddle is de-epithelialized and the flap is tapered to the desired contour (Fig. 18.3). The packing sponges are removed from the recipient site and the flap is stretched out within the facial pocket. The flap is secured around the anastomosis and is also sutured to the periosteum of the zygoma and infraorbital rim to minimize downward migration of the flap. The fascial extensions are secured to the overlying skin with through and through nylon sutures tied over petroleum gauze bolsters (Fig. 18.4). Final insetting and contouring of the flap is confirmed with the patient in the sitting position. The flap is monitored clinically by Doppler signal analysis over the pedicle anastomosis. The facial flap is closed over a closed suction drain placed in the subcutaneous plane.

Postoperative care

The patient should be monitored either in the recovery room or in a specialized unit with nurses trained to care for free flaps. The patients should receive a rectal aspirin in the recovery room and this should continue orally for 1–3 months. The patient should be given adequate hydration to maintain a minimum urine output of 1 mL/kg/hour. Blood pressure should be maintained with a mean arterial pressure greater than 60 mm Hg. Drops in systolic blood pressure should be corrected with fluid boluses or the administration of blood products. The use of vasopressors should be avoided unless absolutely necessary. This needs to be mentioned to your anesthesia colleagues prior to the case as well. In our experience, the majority of our flaps are not monitored. In the event a flap requires monitoring, the flap is monitored every fifteen minutes for two hours, every half hour for the next two hours, and then every one hour thereafter. The average hospital day for these patients is 2–3 days. The facial drain is removed prior to discharge and the donor site drains are removed on day seven along with the facial bolsters and sutures. Ancillary procedures are often necessary to recontour the flap; however, they are mostly minor and are often deferred until the patient is at least five months postoperative (Figs 18.5, 18.6).

Fig. 18.5 A, C, Preoperative views of a 26-year-old female with left-sided hemifacial atrophy. B, D, Postoperative appearance of the patient (2 years later) after parascapular flap.

Reproduced with permission from Saadeh PB, Chang CC, Warren SM, et al. Microsurgical correction of facial contour deformities in patients with craniofacial malformations: a 15-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121(6):368e–378e.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Accurately identify the contour deformity in three dimensions with the patient in the sitting position.

• In designing the parascapular flap, ensure that the origin of the circumflex scapular artery is included.

• Fascial extensions can be incorporated in to the flap that extends well beyond the limits of the skin paddle. These extensions can be folded upon itself to augment subtle contour deformities.

• Flap revisions and other ancillary procedures are frequently necessary to maximize the aesthetic result. This should be discussed with the patient preoperatively.

• Always place adequate tissue volume in the malar region. It is almost impossible to over augment this area.

Pitfalls

• Deficiencies in skeletal support will not be corrected by soft tissue augmentation alone. This must be assessed preoperatively and if necessary a vascularized segment of scapula can be incorporated into the flap.

• Designing a skin paddle width greater than 10 cm may preclude primary closure of the donor site or lead to unsightly scarring.

• Failure to dissect the subcutaneous facial pocket 1cm beyond the boundaries of the facial asymmetry may cause a noticeable transition zone.

• Failure to stretch the free flap out beyond even its original dimensions causes the flap to slide within itself giving the impression that the entire flap has dropped.

• If the superficial temporal vessels are inadequate recipient vessels and a neck incision is required, do not connect these incisions as this may result in a prominent scar. Make a separate incision parallel to the natural neck creases.

Summary of steps

1. Contour deformities are marked in three dimensions with the patient in the upright position.

2. The skin paddle is designed to include the circumflex scapular artery and has a width less than 10 cm wide.

3. The skin paddle is incised and dissected through the deep fascia. The flap is raised in a caudal to cephalad direction.

4. Fascial extensions of the dorsal thoracic fascia and/or vascularized scapula are incorporated into the flap as needed.

5. A limited preauricular incision is made and the superficial temporal vessels are identified. If these vessels are inadequate, a separate incision is made in the neck to identify other recipient vessels.

6. Dissection of the facial pocket is carried out in the subcutaneous plane and extends 1 cm beyond the limits of the facial asymmetry.

7. The flap is secured and microvascular anastomoses are performed.

8. The skin paddle is de-epithelialized and the flap is splayed out across the face in the subcutaneous facial pocket.

9. The flap is secured to the periosteum of the zygoma and high on the lateral orbital rim to prevent descent of the soft tissue.

10. The fascial extensions are folded as necessary to augment thin areas, as well as, the transition zones.

11. The flap is secured to the overlying skin with 4-0 nylons tied over a bolster.

12. The patient is returned to the upright position for final contouring.

13. The back and facial flaps are closed over a closed drain.

dos Santos LF. The vascular anatomy and dissection of the free scapular flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:599–603.

Longaker MT, Flynn A, Siebert JW. Microsurgical correction of bilateral facial contour deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:951–957.

Longaker MT, Siebert JW. Microsurgical correction of facial contour in congenital craniofacial malformations: the marriage of hard and soft tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:942–950.

Longaker MT, Siebert JW. Microvascular free-flap correction of severe hemifacial atrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:800–809.

Nassif TM, Vidal L, Bovet JL, Baudet J. The parascapular flap: a new cutaneous microsurgical free flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:591–600.

Saadeh PB, Chang CC, Warren SM, Reavey P, McCarthy JG, Siebert JW. Microsurgical correction of facial contour deformities in patients with craniofacial malformations: a 15-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:368e–378e.

Siebert JW, Anson G, Longaker MT. Microsurgical correction of facial asymmetry in 60 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(2):354–363.

Siebert JW, Longaker MT, Angrigiani C. The inframammary extended circumflex scapular flap: an aesthetic improvement of the parascapular flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:70–77.

Siebert JW, Longaker MT. Aesthetic facial contour reconstruction with microvascular free flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:361–366.