Aesthetic Alteration of the Soft Tissues of the Neck and Lower Face

Evaluation and Surgery

I agree with Fritz Barton when he stated the following: “The shape of the human face is composed of a skeletal bony framework that is covered by a soft tissue envelope. Overall, skeletal proportions are probably the most important component of facial attractiveness.”7

In my experience, the absence of an attractive cervical–mental (neck–mandibular) angle most often is the result of a developmental mandibular deficiency that predisposes the affected individual to loose lower cheek and neck skin, the noticeable bunching of fat in the neck area, and the eventual presence of visible platysma bands that worsens and becomes less attractive with age (see Chapters 19, 23, and 25).

Aging of the Facial Soft-Tissue Envelope

Background

The layers of the face encompass the skin; the underlying soft tissues, including the fat (subcutaneous and deep); the mimetic muscles (superficial and deep); the investing fascia, which is known as the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS); the retaining ligaments; and the skeletal structural support system (bones, cartilage, and teeth).4,18 The soft tissues of the face will naturally descend with age, which will result in progressive laxity and ptosis of the skin, the subcutaneous tissue, the fat, and the fascia (i.e., the SMAS–platysma layer) as well as the retaining ligaments. The facial fat (subcutaneous and deep) may either atrophy (i.e., as a result of resorption) or hypertrophy (i.e., increase in volume), and it is also affected by gravity over time. Facial aging is dynamic and cumulative, and it is also affected by hormonal and degenerative changes in the soft tissues. An understanding of the pertinent biochemical and histologic changes that tend to occur in the facial soft tissues with age and through environmental exposures is an important aspect to consider when developing a reconstruction and rejuvenation treatment plan.

Soft-tissue aging is affected by genetic aspects, hormonal changes, and environmental influences. For some individuals, the deeper soft-tissue envelope remains well preserved while the superficial surface of the skin appears weathered. For others, the surface skin remains youthful while the deeper soft-tissue envelope loses structural landmarks with cutaneous laxity. Extrinsic (environmental) forces that are working on the skin include dehydration, inadequate nutrition, temperature extremes, traumatic influences, chronic exposure to strong ultraviolet sunlight, toxins (e.g., cigarette smoke), and gravity. The intrinsic (genetic) effects have to do with the individual’s basic soft tissues and their skeletal morphology.15,73 Environmental (extrinsic) factors primarily result in dysplasia and structural alteration of the dermal and epidermal layers of the skin, whereas intrinsic (genetic) effects on the skin may result in atrophy and the loss of structural dermal and epidermal components.19,20,29,84 An individual’s hormone levels throughout life are also known to have significant effects on the aging process.30 Aging is associated with declining levels of several hormones, and it is gender dependent. It is known that, in women, declining estrogen levels are associated with cutaneous changes, many of which can be reversed or improved via estrogen supplementation. Studies of postmenopausal women indicate that estrogen deprivation is associated with dryness, atrophy, fine wrinkling, poor healing, and hot flashes.30,60 Epidermal thinning, declining dermal collagen content, diminished skin moisture, tissue laxity, and impaired wound healing have been reported among postmenopausal women. The soft-tissue effects of changing hormonal levels with age in males are less well studied but presumed to be of equal importance. The cumulative intrinsic (genetic) effects on the skin can be seen histologically as epidermal thinning, changes in the morphology of the keratinocytes, and a decrease in the number of Langerhans cells and melanocytes. Environmental (extrinsic) aging effects on the skin result in keratinocytic dysplasia and the accumulation of solar elastosis, and they can result in cutaneous carcinogenesis (e.g., basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma).

All individuals experience some degree of both extrinsic (environmental) and intrinsic (genetic) aging simultaneously (Fig. 40-1). The genetic variability of an individual’s skeletal framework and the degree and pace of soft-tissue aging in each tissue layer makes a uniform template for facial rejuvenation impractical. Visually, as the intrinsic and extrinsic aging of the skin progress, there will be pigmentary abnormalities, wrinkles (rhytids), and texture irregularities that may result in a “weathered” appearance. Current thinking about aging also involves the concept that the gain or loss of fat volume within the deep compartments leads to changes in the shape and contour of the face.20 By contrast, soft-tissue folds occur at the transition points between the thicker and thinner superficial fat compartments. The transition points cause nasolabial folds, labiomental folds, submental creases, and preauricular folds.65,67 In the upper third of the face, around the eyes, researchers have found that suborbicularis oculi fat is composed of two distinct anatomic compartments: the medial limbus and the lateral canthus region. These researchers have also confirmed that the lateral suborbicularis oculi fat extends from the lateral canthus to the lateral orbital thickening.7 The deep medial cheek fat is the most medial of the periorbital deep fat compartments.51 In current clinical practice, periorbital rejuvenation relies more on soft-tissue augmentation and rearrangement than on tissue removal. In the midface, progressive skin laxity is often combined with the resorption of subcutaneous fat and gravitational effects to result in characteristic changes in the soft-tissue envelope.65 In the lower third of the face, there may be ptosis of the chin soft tissues, a loss of the delineation between the jawline and the neck, the development of characteristic jowls, and looseness in the neck skin (which, in the extreme, is characterized as resembling a “turkey gobble”). In many individuals, prominent vertical platysma bands develop in the submental region, and there is often fat hypertrophy in the submental and submandibular regions. These aging effects further hide or eliminate an otherwise attractive and youthful neck–jaw angle.

Figure 40-1 A 46-year-old woman first arrived for the surgical assessment of a longstanding bony mass in the left forehead region. She underwent a computed tomography scan that confirmed an osteoma without intracranial involvement. She elected to not undergo biopsy, recontouring, or removal at that time. She returned 13 years later, when she was 59 years old, to discuss facial aging. Her concerns included webbing (platysma bands) and loose skin of the neck; heavy jowls; marionette lines; deep nasolabial folds; puffiness and irregularities of the lower eyelids; hollowing in the temporal and cheek regions; deepening of the labiomental crease; and vertical wrinkles of the upper lip. She had undergone Restylane injections of the nasolabial folds, the marionette lines, the labiomental crease, and the lower eyelids with another clinician but without satisfactory improvement. She also had a short face growth pattern (i.e., maxillomandibular deficiency). During her teenage years, she had undergone camouflage orthodontic treatment that included upper bicuspid extractions to achieve a neutralized occlusion. There was no dental show with the upper lip in repose. With broad smile, only half of the maxillary incisors were visible. The upper lip appeared to have lengthened slightly, and the lips appeared to be more deflated (as compared with images taken when the patient was 46 years old). She stated that she received frequent comments about looking “sad” or “unhappy.” She had a history of an inability to breathe well through the nose, loud snoring, restless sleeping, and excessive daytime fatigue. An attended polysomnogram was carried out and confirmed obstructive sleep apnea, with a respiratory disturbance index of 24 events/hour with desaturations of up to 85%. A comprehensive approach to improve dental health, open the upper airway, and enhance facial aesthetics was planned (see Chapters 23 and 25). A, Frontal facial views at 46 and 59 years of age. B, Oblique facial views at 46 and 59 years of age. C, Profile facial views at 46 and 59 years of age.

Frequent Soft-Tissue Facial Aging Characteristics

• Forehead (horizontal) and glabellar (vertical) creases

• Ptosis (drooping) of the lateral eyebrows

• Lower eyelid laxity and wrinkles

• Lower eyelid (puffy) visible bags

• Deepening of the nasojugal grooves and the palpebral malar grooves

• Ptosis (drooping) of the malar soft tissues

• Generalized facial skin laxity*

• Deepening of the nasolabial folds*

• Loss of neck definition (neck–jaw angle) and excess fat collection (hypertrophy) in the neck*

• Deep platysmal bands that are visible in repose and often more obvious with function (e.g., facial expression)*

Basic Principles of Midface and Neck Aging and Rejuvenation

Achieve Facial Harmony

The goal is to help the individual look more like the way they used to look rather than severe, operated on, or unnatural.44,79,94,95 The recognition of any longstanding maxillomandibular skeletal disharmonies is essential to the achievement of enhanced facial aesthetics. If the surgeon attempts to ignore baseline skeletal deformities and then overcompensates with excessive soft-tissue maneuvers, the outcome is likely to be suboptimal. Amateurish or overdone face lifts often look excessively taut, radically defatted, or overfilled (e.g., fat grafts, artificial fillers), or they may involve irregularities from deep layer soft-tissue manipulation. The “overoperated” face may also look startling and unnatural from too much soft-tissue surgical alteration in just one region or layer of the face while ignoring the others. The entire face and all of its layers should be analyzed and given consideration before focusing on just one aspect or technique for rejuvenation.

Achieve Volume Redistribution rather than Skin Tension

Throughout the body, the soft tissues external to the skeleton are anchored to the bony framework by osseocutaneous ligaments that pass directly from the dermis to the periosteum in bare areas where there are no muscles that separate them.22,39,49,62,63,67,80 The most prominent of these retaining ligaments in the head and neck are in the cheek and along the lateral border of the mandible. The retaining ligaments that partition the cheek fat from the neck are called the mandibular septum. A face lift that simply undermines the cheek soft tissues followed by excessive skin resection and then wound closure under tension does not simultaneously manage the deeper soft tissues. Therefore, in these circumstances, skin undermining and resection alone will rarely achieve an attractive or youthful face. This limited “skin-only” approach to face lifting with excessive skin resection may also lead to unsightly scars, flap necrosis, or, more commonly, distortions of key landmarks with the loss of the natural facial curvatures. The use of face-lift techniques that also modestly redistribute the deep soft-tissue layers (i.e., the SMAS–platysma layer) in combination with conservative skin removal and relaxed wound closure will often result in the more pleasing contours that are associated with a youthful and attractive appearance.

Recognize the Presence of Fat Atrophy and Hypertrophy

The process of aging involves not only gravitational effects on the soft tissues and degenerative changes of the skin but, in many cases, noticeable soft-tissue volume loss (deflation) through the atrophy (resorption) of the fat.10,29,42,66,68,70,72,81 Frequent visual effects of descent in the face include the deepening of the nasolabial folds, ptosis of the malar portion of the superficial fat, and the accumulation of fat in the jowls. The classic effects of deflation are seen most frequently in individuals who have had lifelong thinness of the face. The fat atrophy in these individuals is often visually seen in the temporal fossa, periorbital, buccal, and perioral regions. In other individuals, a pattern of simultaneous face and neck fat hypertrophy as a result of weight gain will occur with age. To avoid an amateurish face lift, a good general rule for the surgeon to follow is to only cautiously remove any fat above the inferior border of the mandible and to be sure that an appropriate amount of fat is removed below the mandibular inferior border. Although adding fat to atrophied regions of the face is beneficial in principle, in many individuals, the long-term success of these techniques (i.e., autogenous fat grafting or the use of artificial fillers) to achieve a natural-appearing rejuvenation remains a work in progress.10

Recognize Degenerative Changes in the Skin

Face lifting will address gravitational changes in the soft-tissue envelope, but it does not have an effect on the quality of the soft tissues themselves.60,85 Face-lift procedures will not treat wrinkles (rhytids), sun damage, creases, or age-related pigmentation. If feasible, fine wrinkles and irregular pigmentation are treated with good-quality skin care and possibly resurfacing procedures (e.g., dermabrasion, chemical peel, laser). Preventative measures of avoiding excessive ultraviolet light exposure, cigarette smoke, temperature extremes, dehydration, and nutritional deficiencies are important.

Recognize the Negative Effects of Any Baseline Maxillomandibular Skeletal Disharmony

Significant variation occurs in the aging of each individual’s face and neck. Recognition that the shape of the neck is fundamentally determined by the maxillomandibular skeleton is essential (Figs. 40-1 through 40-4).13,16,24,32,69,71,93 The ideal neck configuration requires a well-proportioned facial skeleton; it is often described as having a cervical–mental (neck–jaw) angle of 105 to 120 degrees and a distinct mandibular inferior border. Interestingly, despite various assertions and opinions by a handful of authors, in the absence of a loss of the teeth or significant alteration of the dentition through either natural attrition or dental restorative procedures, no convincing data confirms significant changes in the maxillofacial skeleton with aging (see Chapter 25).*

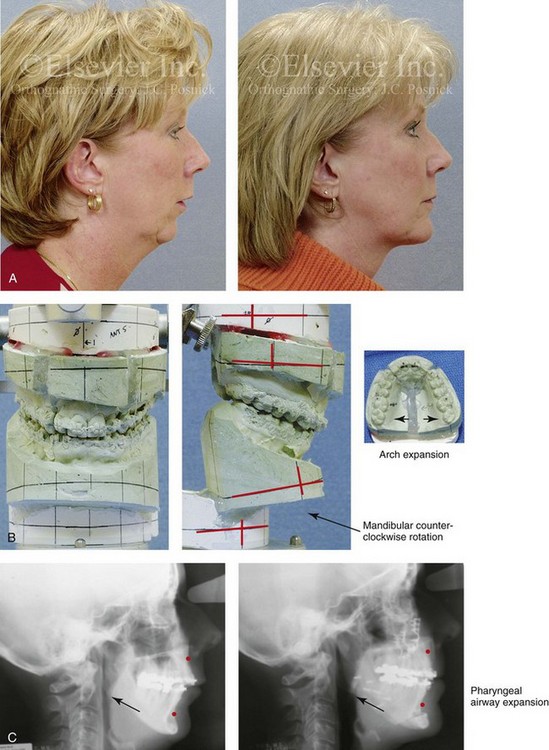

Figure 40-2 A woman in her mid 50s was referred from her general dentist to an orthodontist for the management of a longstanding Angle Class II excess overjet malocclusion that had gradually resulted in deterioration of the posterior dentition. The orthodontist recognized that the malocclusion resulted from a retrusive mandible and a constricted maxilla. With referral for surgical evaluation, the patient was found to have a developmental jaw deformity, chronic obstructed nasal breathing, and a sleep history that was consistent with obstructive sleep apnea. Unfavorable facial aging with a desire for an improved neck–chin angle was also discussed. An attended polysomnogram confirmed moderate obstructive sleep apnea. The patient agreed to proceed with orthodontic treatment that included lower first bicuspid extractions to relieve dental compensation in combination with jaw, intranasal, and facial surgery. The objectives were to open the upper airway, enhance the facial aesthetics, and achieve improved long-term dental health. The patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, arch expansion, and correction of the curve of Spee); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction (see Fig. 25-1). A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. Note the improved A-point–to–B-point relationship that was achieved as a result of maxillomandibular counterclockwise rotation. B, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. C, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery. Note the improved posterior airway space with pharyngeal expansion as a result of the orthognathic procedures.

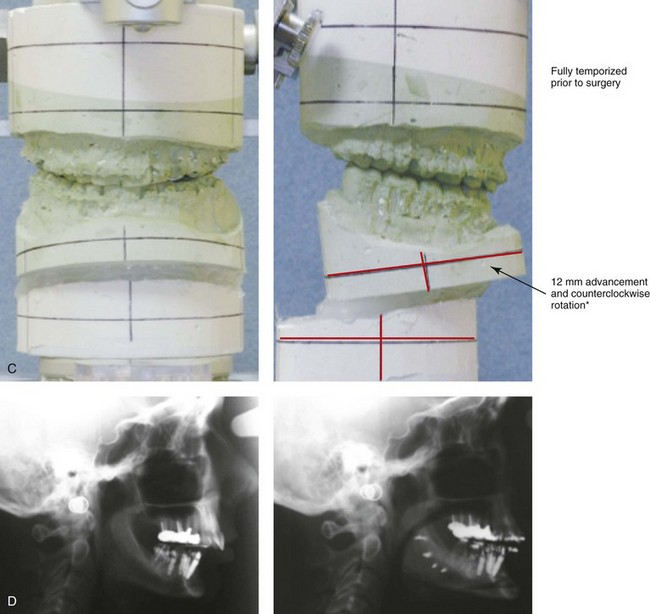

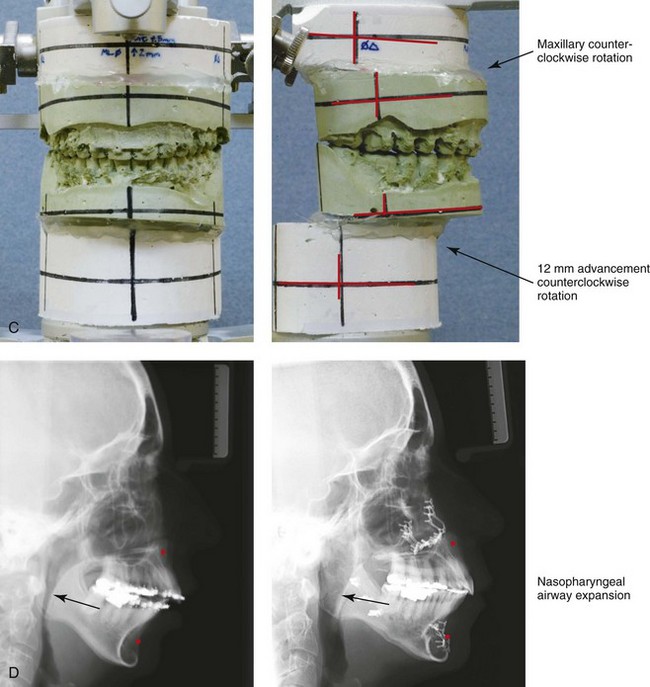

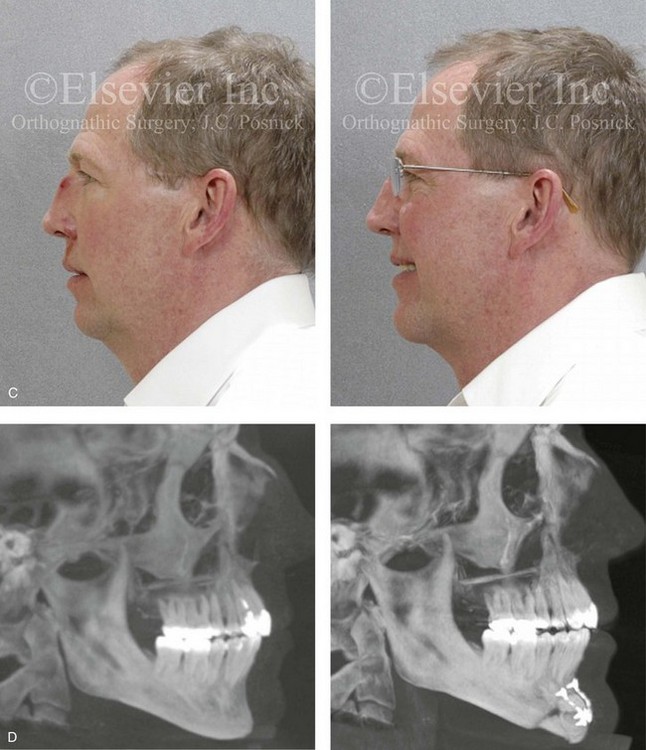

Figure 40-3 A woman in her early 50s was referred by a prosthodontist for surgical evaluation. There had been a gradual deterioration of the dentition, at least partially as a result of the longstanding skeletal Class II excess overjet deep-bite malocclusion. Head and neck evaluation confirmed a retrusive mandible that also resulted in retroglossal airway obstruction. A desire for improved profile aesthetics was also discussed. A comprehensive approach to dental rehabilitation, opening the upper airway, and facial rejuvenation and reconstruction was selected. Coordinated endodontic, orthodontic, periodontic, prosthodontic, and surgical care was required. Periodontal treatment, extractions, dental implant placement, restorative temporization, and orthodontic alignment were carried out. This was followed by surgery that included bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting; and an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication). This was then followed by crown lengthening and final dental restorations (see Fig. 25-6). A, Profile views before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction and dental rehabilitation. C, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Figure 40-4 A woman in her mid 50s was seen by a prosthodontist for the management of a deteriorating posterior dentition. She was confirmed to have secondary dental trauma as a result of a longstanding malocclusion. She was referred to an orthodontist and then for surgical assessment. Head and neck evaluation confirmed a short face growth pattern with a Class II excess overjet deep bite and constricted maxillary arch malocclusion. She had a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing, and her history was suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea (this was confirmed with an attended polysomnogram). Facial aesthetic concerns included downturned corners of the mouth, deep perioral creases, early jowl formation, weak profile, an obtuse neck–chin angle, and loose skin around the neck. The patient agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. Periodontal evaluation, initial restorations, and orthodontic decompensation preceded surgery. The patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and vertical adjustment); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); an anterior approach to the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal recontouring (see Fig. 25-7). A, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. B, Profile views before and after treatment. C, Articulated dental casts that indicate model planning. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Note the improved posterior airway space with pharyngeal expansion as a result of the orthognathic procedures.

Approach to Rejuvenation Surgery of the Neck and Lower Face

Traditional Face-Lift Approach to Rejuvenation

Face lifting was first performed during the early 1900s and involved skin incisions around the ears, limited skin-flap undermining, and then skin excision before wound closure. In 1859, Gray defined a unique deep layer of tissue just below the facial skin that was described as “superficial subcutaneous fascia.” Not much changed until the 1970s, when both Tessier and Skoog independently described the aesthetic benefit of manipulating this superficial subcutaneous fascia as a separate component during face lifting for rejuvenation purposes. The superficial subcutaneous fascia was recognized as investing the platysma muscles and fusing to the parotid fascia as the facial extension of the cervical investing fascia. It later came to be called the superficial muscular aponeurotic system or SMAS, as mentioned previously.48 The SMAS envelopes the platysma muscles within the neck and the lower cheek region. Superiorly, it terminates as the investing layer of the superficial mimetic muscles. Laterally, it fuses with the parotid capsule. Superiorly, it passes over the zygomatic arch to join the temporoparietal fascia. Tessier and Skoog were the first to include as part of the face-lift technique not just the undermining and excision of the skin but also the management of the so-called SMAS–platysma layer. This required unique incisions, undermining, redraping, and tightening of the SMAS–platysma as part of the face-lifting procedure. Since the initial contributions of Tessier and Skoog, every conceivable recommendation has been made by surgeons for dissecting, undermining, excising, adding to, or removing virtually all of the tissue layers and cell types in the head and neck to further enhance the aesthetic outcome.2–5,8,18,21,31,47,50,59,77,78 Many of the “innovations” in the area of face lifting have proven to have little additional long-term value, and some have resulted in increased complications and prolonged recoveries. This was confirmed by Chang and colleagues in a recently completed systematic review and comparison of efficacy and complication rates among a variety of face-lift techniques. The authors conclude that there are pros and cons to each of a variety of face-lift techniques and that there is no clear evidence that one is routinely superior to another.9

A well-designed traditional face lift often confers much benefit to the jowls (i.e., the mandibular line) and the neck (Figs. 40-5 through 40-10). It can be an effective way to soften the nasolabial folds, to lift the jowls back into the face, to relieve the platysmal bands, to remove the loose skin and excess fat of the neck, and to restore the neck–jaw angle back to its baseline. This can change the overall facial shape from rectangular back to that of a heart in a way that no other soft-tissue treatment modality can provide. The basic traditional face-lift approach requires the consideration of the following:

Figure 40-5 A woman in her early 50s arrived for the evaluation of facial aging. She had satisfactory skeletal proportions and no significant surface skin layer aging effects. She requested surgery to diminish her jowls, to soften her nasolabial folds, and to reduce the amount of loose skin in her neck region. She underwent a face lift that included periauricular and submental incisions; cheek and neck flap elevation; superficial musculo-aponeurotic system flap elevation with postauricular transposition; neck defatting; vertical platysma muscle plication; and skin resection and redraping. Asymmetric upper eyelid ptosis was not addressed. A, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. B, Profile views before and after surgery.

Figure 40-6 A 50-year-old woman arrived for the evaluation of facial aging. She has satisfactory skeletal proportions and minimal skin surface layer aging effects. She underwent a limited incision brow lift with suspension; blepharoplasty (elliptical excision of the upper eyelid skin and redraping of the lower lid tissue); and a face lift as described in the legend for Fig. 40-5. A, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. B, Profile views before and after surgery.

Figure 40-7 A woman in her late 50s arrived for the evaluation of facial aging. She had satisfactory skeletal proportions but marked surface layer aging effects. She elected to not undergo skin resurfacing procedures. She agreed to a limited incision brow lift with suspension, blepharoplasty (elliptical excision of the upper lid skin and lower lid redraping), and a face lift as described in the legend for Fig. 40-5. A, Frontal views before and after surgery. B, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. C, Profile views before and after surgery.

Figure 40-8 A woman in her early 40s requested an improved neck–chin angle and the relief of hooding of the upper eyelids. She had a short face growth pattern that resulted in mildly deficient lower anterior facial height and horizontal facial projection. She had a good airway and occlusion. There was limited surface skin layer damage and aging effects. She underwent upper blepharoplasty (elliptical skin incision) and a face lift as described in the legend for Fig. 40-5. A, Oblique facial views before and early after surgery. B, Profile views before and early after surgery.

Figure 40-9 A woman in her early 50s with facial aging concerns. She had a mild long face growth pattern but a satisfactory occlusion. The lower anterior facial height was slightly increased, which resulted in mild lip incompetence and mentalis strain; this resulted in accentuated perioral creases. She agreed to blepharoplasty (elliptical excision of the upper lid skin and redraping of the lower lid tissue); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and a face lift as described in the legend for Fig. 40-5. A, Frontal views before and after surgery. B, Profile views before and after surgery. Note the relief of the perioral folds and the mentalis strain as a result of vertical reduction and advancement genioplasty.

Figure 40-10 A woman in her late 50s arrived for the evaluation of facial aging. She had satisfactory skeletal proportions and occlusion. Her skin was thick but did not have major ultraviolet light damage. She agreed to a limited incision brow lift with suspension; blepharoplasty (elliptical excision of the upper eyelid skin and fat removal and redraping from the lower lids); and a face lift as described in the legend for Fig. 40-5. A, Frontal views in repose before and after rejuvenation. B, Frontal views with smile before and after rejuvenation. C, Oblique facial views before and after rejuvenation. D, Profile views before and after rejuvenation.

• Skin incision placement (i.e., preauricular with temporal extensions and postauricular with occipital extensions)

• Skin flap elevation and undermining (i.e., temporal, cheek, postauricular, neck, and submental regions)

• Supraplatysmal, intraplatysmal, and subplatysmal defatting (e.g., below the inferior border of the mandible and chin, above the thyroid cartilage, and anterior to and above the sternocleidomastoid muscles)

• Platysma muscle management (i.e., vertical plication versus the excision of bands)

• SMAS management (i.e., preauricular SMAS plication versus SMAS elevation with postauricular flap transposition)

• Redraping of the elevated skin flaps (i.e., in a superoposterior vector)

• Excision of redundant skin (e.g., temporal, preauricular, postauricular, occipital)

Anterior Neck (Submental) Approach to Rejuvenation

Background

Changes that occur in the neck with age can alter the natural youthful facial curvatures and angles.* As people age, characteristic changes tend to occur in the skin and throughout the soft-tissue envelope. Soft-tissue rejuvenation procedures that focus on the neck often include the following: 1) cervical flap elevation; 2) the selective removal of fat (above, in between, and below the platysma muscles); 3) the tightening of the platysma muscles (in the neck midline); and 4) the redraping of lax skin (i.e., skin retraction). In the presence of well-proportioned (harmonious) maxillomandibular skeletal structures, the combination of these procedures can generally be carried out to achieve a preferred geometric angle between the cylindrical neck and the straight-line inferior border of the jaw.12,18,23,25–27,34–36,41,46,61,83,94,95

Aging of the neck often presents in one of two classic ways; it is primarily a reflection of the underlying skeletal anatomy. One common pattern is what appears to be a long neck with a sharp neck–jaw angle. This occurs in an individual with preferred proportions and fullness of the jaws. With aging, these patients may develop visible platysmal bands but with the maintenance of a reasonable neck–jaw angle and chin projection. A second common pattern of presentation is seen in individuals with what appears to be a short neck and a poorly defined neck–jaw angle. This is the result of a baseline mandibular deficiency (e.g., combined maxillomandibular deficiency, primary mandibular retrognathia, or a long face growth pattern with sagittal deficiency and clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex; see Figs. 40-2, 40-3, and 40-4). Individuals with this type of neck experience facial aging prematurely and in a more detrimental way. In the presence of sagittal deficiency of the mandible, when any degree of neck soft-tissue laxity occurs and even with small amounts of submental and supraplatysmal fat accumulation, further loss of the clear separation between the chin and neck (i.e., an obtuse neck–jaw angle) can be expected. Skeletal (orthognathic) procedures to reconstruct the jaws toward Euclidean proportions will have a dramatic positive effect on the facial aging of this latter group of individuals (see Figs. 40-2, 40-3, and 40-4). Completing traditional face and neck soft-tissue lifting procedures alone in the presence of a deficient maxillomandibular skeletal framework can be disappointing and, in some cases, disastrous. The surgeon should view the overlying soft-tissues as just the icing on the cake and not as the cake itself. The failure to recognize these anatomic realities is responsible for much clinician frustration and many suboptimal “face-lift” results.

A fundamental clinical observation is that the visual appearance of aging in the neck is greatly influenced by the baseline maxillomandibular skeletal anatomy. The ideal horizontal mandibular plane relative to the vertical cylindrical neck (i.e., an angle of 105 to 120 degrees) will abnormally slump downward and backward when the mandibular skeletal framework is deficient and clockwise rotated (i.e., long face growth pattern; see Chapter 21).

An example of the negative effects of the skeleton on the soft-tissue surface anatomy is seen in the presence of primary mandibular deficiency with excess overjet (see Chapter 19). Not only will the lower lip be flaccid with a deep labiomental fold (curl), but the soft tissues directly over the bony chin are bunched and ptotic, and the soft-tissue structures of the neck are cramped together to result in a double (soft-tissue) chin. In the presence of mandibular deficiency, the chin seems to fall directly into the neck without any semblance of a normal “right-angle” curvature (see Fig. 40-2, A and B).

When both the maxilla and the mandible lack vertical height and horizontal projection (i.e., short face growth pattern; see Chapter 23), the cheeks often appear to be puffy. There will be deep nasolabial folds, heavy jowls, perioral creases, and downturned oral commissures that compound the negative effects of the observed obtuse neck–jaw angle.

Patient Selection

Appropriate patient selection (i.e., for a traditional face lift versus an anterior submental neck lift) is based primarily on the degree of skin laxity. Zins proposed a useful grading scale for neck skin laxity: Grade I (no laxity); Grade II (mild laxity); Grade III (moderate laxity); and Grade IV (severe laxity)95:

Grade I patients may only require closed liposuction. However, even Grade I patients frequently benefit from an open approach to fully access and then remove subplatysmal fat.

Grade II patients are good candidates for an anterior (submental) approach to neck rejuvenation. Their limited lax skin should be expected to retract in a favorable way.

Grade III patients can often be managed with an anterior (submental) approach to the neck. They will require wide cervical flap elevation with meticulous attention to release all septae and ligaments to achieve maximum skin retraction and to avoid unfavorable visible irregularities after surgery. Full disclosure with regard to the limitations of an anterior neck lift and the setting of realistic expectations are especially relevant for the Grade III patient to avoid later disappointment.

Grade IV patients are not good candidates for an anterior-only approach to the neck and should be considered for a traditional face lift. Unless skin is excised (i.e., with a traditional face-lift approach), residual laxity will provide a suboptimal result.

Cervical Flap Elevation and Neck Defatting

Some teenagers and young adults and many middle-aged adults benefit aesthetically from neck defatting.1 The fat removal is typically carried out in the region below the inferior border of the mandible, above the thyroid cartilage, and anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Whether by liposuction, direct scissors excision, or a combination of the two the objective is to remove appropriate adipose cells deep to the skin and superficial to the platysma muscles. Below the chin in the midline, where there is a tendency for the separation of the platysma muscles, excess fat also frequently accumulates. If the platysma muscles are in continuity (i.e., if there is no dehiscence), then surgical separation is required to expose the excess submental fat for removal.

Generally, the cervical skin undermining extends up to the inferior border of the mandible and chin, laterally to and over the surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscles, and inferiorly past the thyroid cartilage toward the clavicles. In those with only moderate skin laxity, adequate release of all cutaneous septae and cutaneous ligaments will generally allow for skin contracture during healing without the need for skin resection. After surgery, skin irregularities and adhesions will persist if inadequate undermining was accomplished. A second procedure would then be required to complete the undermining. The surgeon should also avoid uneven fat removal and excessive defatting in the neck, because this can result in contour irregularities between the skin and the platysma muscles. Ptotic submandibular salivary glands may also affect an otherwise satisfactory result. This author does not favor either partial submandibular gland resection or intracapsular gland dissection and repositioning, because the incidence of associated complications is high.28,76,82 Close to the midline and just below the chin, overaggressive fat removal may result in an unnatural concavity, which is a stigma of an amateurish cervical defatting. In some cases, prominent hypertrophy digastric muscles may benefit from “shaving” (i.e., scissors excision) in the region just below the chin.11

Management of the Platysma Muscles and Cervical Fascia

The anterior (submental) neck approach is preferred to a traditional face lift in individuals with reasonable skin elasticity who are not overly concerned about the aging of their cheek region (i.e., aging of the jowls and the nasolabial folds). An anterior submental approach will not satisfy individuals who need and expect improvements in the frontal view (i.e., a reduction of the jowls, a softening of the nasolabial folds, and the management of the malar and eyelid regions) or in those with moderate or greater degrees of neck skin laxity.94,95

Anterior Neck (Submental) Approach: Step-By-Step Surgical Technique (Fig. 40-11) ( Video 16)

Video 16)

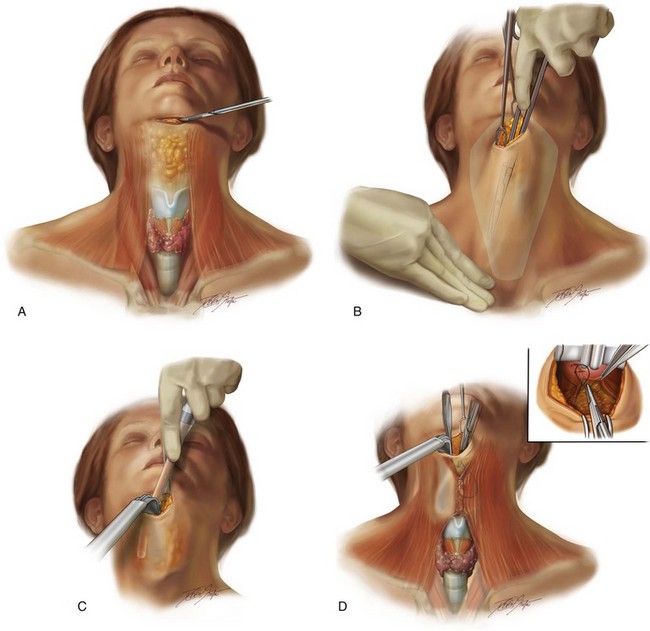

Positioning on the Operating Room Table

Figure 40-11 Illustrations that demonstrate the anterior (submental) approach for neck rejuvenation as described in the text. A, Illustration of the neck region in the operating room in preparation for an anterior (submental) rejuvenation procedure. The submental incision is marked. A knife (no. 15 blade) is used to initiate the skin incision. Important underlying landmarks are indicated, including the thyroid cartilage; the sternocleidomastoid muscle on each side; the platysma muscles with central dehiscence; and the accumulated fat. B, Illustration that demonstrates the elevation of the cervical flaps after the completion of the submental incision. Instruments that are in place include double skin hooks with one at each side of the submental wound. The assistant’s hands are positioned over the clavicle to provide counter tension to the double hook located at the submental incision. In this way, the neck skin in the region of the cervical flap elevation is taut. A Stevens scissors is then used to complete the dissection in the exact location where the neck skin is placed under tension. The green shaded area indicates the extent of planned supraplatysma dissection for cervical flap elevation. C, Illustration after cervical flap elevation that demonstrates liposuction in progress. A no. 7 curved plastic cannula is used in the supraplatysma plane laterally and in the subplatysma in the midline below the chin. D, Illustration that demonstrates vertical platysma muscle plication in progress. A lighted retractor is in place to provide exposure for the direct visualization of the platysma muscle dehiscence. The surgeon uses a long needle driver and a long forceps to place interrupted sutures (3-0 Vicryl) for the achievement of vertical platysma muscle plication. There is also a close-up illustration of the wound with a lighted retractor in place. The long forceps elevates the edge of the platysma muscle on the right side. A needle driver is used to place a suture through the elevated platysma edge. Several interrupted sutures are already in place from just above the thyroid cartilage.

Anesthesia

• When the procedure is carried out in conjunction with orthognathic surgery, general anesthesia is administered through a nasotracheal cuffed (RAE) tube. The nasotracheal tube will already have been secured to the cartilaginous septum with suture (#0 Ethibond).

• The application of ophthalmic eye ointment and the insertion of corneal shields deep to the eyelids will also already have been performed.

Preparation and Draping

• After the completion of the orthognathic procedures (including the removal of the throat pack and the placement of interocclusal elastics), the patient is reprepped, and additional sterile drapes are placed over the ones that are already there.

• Reprep entire neck below the clavicles, the face, and the postauricular regions with the use of Betadine solution (do not use soap, alcohol, Hibiclens, and so on).

• Draping is completed with exposure of the neck just inferior to the sternal notch and clavicles. Exposure of the entire neck, the external ears, and the lower face is also accomplished.

Surgical Markings

• Locate and use a surgical pen to mark the extent of planned cervical flap elevation, including the following:

• The inferior border of the mandible and the chin

• Locate and use a surgical pen to mark the proposed 3- to 4-cm submental incision.

Elevation of the Cervical Flaps

• A wide double skin hook is placed on either side of the complete submental incision. With the use of the skin hooks spreading in opposing directions, tension separates the wound.

• A long Stevens scissors is used to elevate the cervical flaps. Stretch-tension is achieved on the skin of the cervical flap to be elevated; this is accomplished with the double skin hook at the submental wound and the assistant’s hands over the neck skin above the clavicle. The Stevens scissors is then used to blindly separate the skin and the subcutaneous flap from the underlying platysma muscles throughout all planned locations on both sides of the neck.

• The dissection continues down past the thyroid cartilage toward the clavicles and laterally just above the anterior border of each sternocleidomastoid muscle.

• The dissection continues superiorly to the inferior border of the mandible. Caution is used to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular branch of cranial nerve VII.

• The lighted retractor is then used to confirm the complete release of the cervical flaps from all cutaneous septae and cutaneous ligaments.

• The lighted retractor is also used to confirm adequate hemostasis. A guarded electrocautery device is used to control any bleeding vessels.

Defatting Above, in Between, and Below the Platysma Muscles

• Supraplatysma defatting is carried out via open liposuction with the use of a no. 7 curved plastic cannula.

• With the use of a lighted retractor under direct vision, any remaining clumps of fat are extracted via either liposuction or sharp scissors removal.

• If the platysma muscles are intact (i.e., without dehiscence), they are separated in the midline just below the chin to expose the submental fat pad.

• Subplatysmal fat is removed with the use of open liposuction via a no. 7 curved plastic cannula or sharp scissors excision.

• In the interdigastric space, fat is removed or resected to be flush with the anterior digastric bellies.

• If there is prominent elevation of the digastric muscles, the edges are resected with a scissors.

Platysmaplasty

• Consideration is given to tightening the platysma muscle sling. Dehiscence of the muscles in the midline may be seen from the thyroid cartilage below to the bony chin above.

• The lighted retractor is useful to directly visualize the platysma muscles.

• Vertical platysma muscle plication is carried out with interrupted sutures (3-0 Vicryl).

Skin Closure

• Before wound closure, the redraped cervical flaps are inspected to confirm the absence of irregularities caused by residual attached cutaneous septae or cutaneous ligaments.

• The wounds are again inspected with the lighted retractor and the electrocautery device to confirm adequate hemostasis.

• If oozing is poorly controlled, consideration is given to the placement of a suction drain.

• The fascia layer of the submental wound is closed with interrupted sutures (5-0 Vicryl).

• The skin edges are approximated with running suture (6-0 nylon).

Postoperative Care

• Two days after surgery, the chin/neck dressing is removed, and the patient is allowed to shower (including the head and neck region) and shampoo the hair. The dressing is replaced by the patient for an additional 3 days.

• The dressing is removed daily for showering and then replaced until 5 days after surgery.

• Submental sutures are removed on the fifth postoperative day.

• Antibiotics are discontinued after 5 days.

• No sports participation or direct facial trauma is allowed for 5 weeks.

Complications and Unfavorable Results

Skin Necrosis

The incidence of skin necrosis in properly selected patients and with the use of sound flap elevation techniques is uncommon. The occurrence of flap necrosis may be significantly higher in those with vascular occlusive disorders and in smokers (see Chapters 16 and 25).

Residual Submental Fullness or Hollowing

Subplatysma midline defatting is carried out to reduce excess fullness. After the separation of the platysma muscles, defatting down to the level of the digastric muscles is usually beneficial.11 If residual fullness remains as a result of inadequate fat removal, this can be managed secondarily to finish the job. Excessive defatting in this region often creates a submental hollow with a resulting “operated” look. Secondary grafting may be beneficial.

Facial Aging and Rejuvenation: Treatment Pitfalls

Pitfalls of a “Soft-Tissue–Only Approach” to Facial Rejuvenation

• The injection of non-autogenous “fillers”

• The injection of autogenous fat grafts

• Skin care and resurfacing techniques

• The injection of fillers and fat grafts to augment the recognized skeletal deficiencies

• The placement of “hard” implants (e.g., Silastic, porous polyethylene) to augment the recognized skeletally deficient regions (i.e., the chin; the angles of the mandible; and the perinasal, infraorbital, and zygomatic regions)

The surgeon may neglect to consider patient-specific smile aesthetics or jaw dysmorphology when discussing treatment options. Interestingly, the patient is not likely to intuitively equate these aspects. In addition, neither the patient nor the surgeon is likely to consider the potential cause-and-effect relationship between skeletal dysmorphology and baseline breathing difficulties (i.e., maxillomandibular deficiency and obstructive sleep apnea; see Chapter 26).

A preferred approach is to educate the patient about pertinent aspects that may go beyond the original chief complaint and the surgeon’s immediate expertise.43,58,78,79,86–92 To best ensure a successful outcome and a satisfied patient, a comprehensive discussion of pertinent findings should precede any compromised treatment delivered (Figs. 40-12 and 40-13).

Figure 40-12 A woman in her 50s requested evaluation for a “weak chin” and unfavorable neck aesthetics. Since her teenage years, she was known to have significant mandibular deficiency and a degree of maxillary hypoplasia. She underwent orthodontic treatment only and has a stable occlusion. Maxillary and mandibular osteotomies with advancement would best restore Euclidean proportions, open the airway, and rejuvenate the face (see Chapters 23 and 25). She was not prepared to undergo further orthodontics or an orthognathic approach. A compromised treatment plan was agreed to that included osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and minimal horizontal advancement) with interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting and an anterior approach to the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication). A, Frontal views before and after surgery. B, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

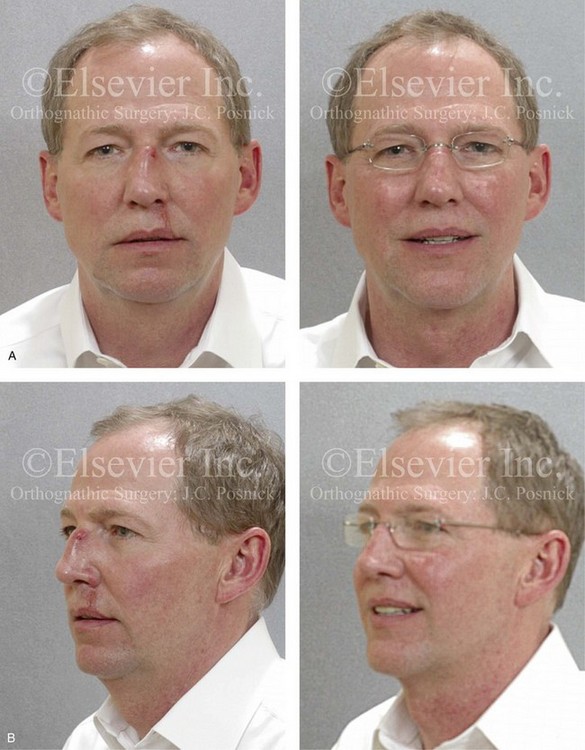

Figure 40-13 A man in his early 50s was in a bicycle accident and sustained a displaced nasal fracture and an upper lip laceration. During the consultation, he also discussed a lifelong concern about a weak profile and, with age, the progressive laxity of the neck soft tissues. A lateral cephalometric and Panorex radiograph confirmed the nasal fracture and the microgenia. The patient had a stable occlusion without excess overjet. The nasal fracture required closed reduction with packing, and the upper lip laceration was approximated with suture for primary closure. The patient also underwent an osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and horizontal advancement) with interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting and an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication). He is shown before and 3 months after the procedures. A, Frontal views before and after surgery. B, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. C, Profile views before and after surgery. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

Pitfalls of a “Dental-Only Approach” to Facial Rejuvenation

When a middle-aged woman consults a restorative dentist or an orthodontist with a chief complaint of an unattractive smile, it is tempting for the clinician to only consider the alignment, shape, and color of the teeth (see Fig. 40-3). If the dentition and occlusion cannot be adequately improved through a combination of restorative dentistry and orthodontic mechanics, a dentofacial deformity should be suspected. The consulted orthognathic surgeon may then be tempted to limit the discussion to the “simplest way” to correct the occlusion (i.e., one-jaw surgery) without fully considering skeletal dysmorphology, facial aesthetics, or any baseline upper airway issues (e.g., chronic nasal obstruction, obstructive sleep apnea). For example, the individual with a long face Class II anterior open-bite growth pattern may arrive to the surgeon with a request from the orthodontist to “close the bite.” It may be possible to achieve an acceptable occlusion with surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion and further orthodontic alignment. Doing so may resolve the open bite, but it is unlikely to address the following:

Difficulty achieving an optimal outcome may also occur when the restorative dentist or the orthodontist has overoptimistic expectations of what can be achieved through limited “surgical cosmetic” procedures. For example, the dental team may incorrectly assume that, if they are able to improve the occlusion in an individual with mandibular deficiency, then a chin implant will resolve the aesthetic concerns (see Fig. 38-1). It should be within the collaborative skill set of the treating orthodontist and the consulting orthognathic surgeon to broadly evaluate the patient’s dental rehabilitative, jaw reconstruction, and rejuvenation needs.

Pitfalls of a Segmental Soft-Tissue Approach to Facial Rejuvenation

At times, a surgeon will be asked to perform a limited “segmental” soft-tissue approach to an individual’s facial aging. For example, the patient shown in Fig. 40-14 presents with a degree of brow ptosis; asymmetric upper eyelid ptosis and hooding; lower eyelid fat protrusion; deep nasolabial and perioral folds; heavy jowls; and neck submental soft-tissue fullness that involves all of the layers (i.e., skin, platysma, and fat). There is also notable surface-layer skin aging and a degree of maxillomandibular deficiency.

Figure 40-14 A woman in her mid 50s arrived with a request for neck rejuvenation. Over the years, excess loose skin had developed around her neck. She had a mild degree of maxillomandibular deficiency that was characterized as diminished lower anterior facial height and limited horizontal projection. The surface layer of the skin was thin with spotty pigmentation and wrinkling. She also had significant brow and upper eyelid ptosis. She did not wish to undergo an orthognathic correction, and she refused rejuvenation of the brow and eyelids at this time. She requested a segmental soft-tissue surgical approach that was restricted to the neck and jowls. Her face lift was carried out as described in the legend for Fig. 40-5. The aesthetic results are limited as a result of the inability to manage upper-face soft-tissue aging and the maxillomandibular skeletal deficiency. A, Frontal views before and after surgery. B, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. C, Profile views before and after surgery.

References

1. Bach, DE, Newhouse, RF, Boice, GW. Simultaneous orthognathic surgery and cervicomental liposuction: Clinical and survey results. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991; 71:262.

2. Baker, DC. Lateral SMASectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:509–513.

3. Baker, DC. Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar facelift) with lateral SMAS-ectomy: Evolution and applications. Aesthet Surg J. 2001; 21:14–26.

4. Baker, DC, Nahai, F, Massiha, H, Tonnard, P. Panel discussion: Short scar face lift. Aesthet Surg J. 2005; 25:607–617.

5. Baker, T, Stuzin, J. Personal technique for facelifting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:502–513.

6. Barlett, SP, Grossman, R, Whitaker, LA. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: An anthropometric and histological analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:592–600.

7. Barton, FE. Aesthetic surgery of the face and neck. Aesthet Surg J. 2009; 29:449–463.

8. Biggs, TM. Excision of neck redundancy with single Z-plasty closure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 98:1113–1114.

9. Chang, S, Pusic, A, Rohrich, RJ. A systematic review of comparison of efficacy and complication rates among face-lift techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127:423.

10. Coleman, SR, Grover, R. The anatomy of the aging face: Volume loss and changes in 3 dimensional topography. Aesthet Surg J. 2006; 26:S4–S9.

11. Connell, BF, Shamoun, JM. The significance of digastric muscle contouring rejuvenation of the submental area of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99:1586–1590.

12. Courtiss, EH. Suction lipectomy of the neck. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985; 76:882–889.

13. Donofrio, LM. Fat distribution: A morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000; 26:1107–1112.

14. Doual, JM, Ferri, J, Laude, M. The influence of senescence on craniofacial and cervical morphology in humans. Surg Radiol Anat. 1997; 19:175–183.

15. El Domyati, M, Attia, S, Saleh, F, et al. Intrinsic aging vs photoaging: A comparative histopathological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of skin. Exp Dermatol. 2002; 11:398–405.

16. Enlow, DH. Handbook of facial growth. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1982.

17. Farkas, LG, Eiben, OG, Sivkov, S, et al. Anthropometric measurements of the facial framework in adulthood: Age-related changes in eight age categories in 600 healthy white North Americans of European ancestry from 16 to 90 years of age. J Craniofac Surg. 2004; 15:288–298.

18. Feldman, JJ. Neck lift. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2007.

19. Fisher, GJ, Varani, V, Voorhees, JJ. Looking older: Fibroblast collapse and therapeutic implications. Arch Dermatol. 2008; 144:666–672.

20. Fitzgerald, R, Graivier, MH, Kane, M, et al. Update on facial aging. Aesthet Surg J. 2010; 30(Suppl 1):11S–24S.

21. Fuente del Campo, A, Feldman, JJ, Guyuron, B, Hoeffin, SM. Panel discussion: Treatment of the difficult neck. Aesthet Surg J. 2000; 20:495–501.

22. Furnas, DW. The retaining ligaments of the cheek. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 83:11–16.

23. Goddio, AS. Skin retraction following suction lipectomy by treatment site: A study of 500 procedures in 458 selected subjects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991; 87:66–75.

24. Gonzalez-Ulloa, M, Flores, ES. Senility of the face: Basic study to understand its causes and effects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965; 36:239–246.

25. Gradinger, GP. Anterior cervicoplasty in the male patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:1146–1154.

26. Guerrerosantos, J, Espaillat, L, Morales, F. Muscular lift in cervical rhytidoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974; 54:127.

27. Guyuron, B. Problem neck, hyoid bone, and submental myotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:830–837.

28. Guyuron, B, Jackowe, D, Iamphongsai, S. Basket submandibular gland suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 122:938–943.

29. Guyuron, B, Rowe, DJ, Weinfeld, AB, et al. Factors contributing to the facial aging of identical twins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 123:1321–1331.

30. Hall, G, Phillips, TJ. Estrogen and skin: The effects of estrogen, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 53:555–568.

31. Hamra, S. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 86:53–61.

32. Hayes, RJ, Sarver, DM, Jacobson, AJ. Quantification of cervicomental angle changes with mandibular advancement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994; 105:383–391.

33. Kahn, DM, Shaw, RB. Aging of the bony orbit: A three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Aesthet Surg J. 2008; 28:258–264.

34. Kesselring, UK. Direct approach to the difficult anterior neck region. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1992; 16:277–282.

35. Knize, DM. Limited incision submental lipectomy and platysmaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 101:473–481.

36. Knize, DM. Limited incision submental lipectomy and platysmaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 113:1275–1278.

37. Lambros, V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 120:1367–1376.

38. Lambros, V. Models of facial aging and implications for treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 2008; 35:319–327.

39. Le Louarn, CL, Buthiau, D, Buis, J. Structural aging: The facial recurve concept. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007; 31:213–218.

40. Levine, RA, Garza, JR, Wang, PT, et al. Adult facial growth: Application to aesthetic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003; 7:265–283.

41. Levy, PM. The “Nefertiti lift”: A new technique for specific re-contouring of the jawline. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007; 9:249–252.

42. Little, JW. Volumetric perceptions in midfacial aging with altered priorities for rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:252.

43. Marten, TJ, Feldman, JJ, Connell, BF, Little, WJ. Panel discussion: Treatment of the full obtuse neck. Aesthet Surg J. 2005; 25:387–397.

44. Mendelson, BC, Freeman, ME, Wu, W, Huggins, RJ. Surgical anatomy of the lower face: The premasseter space, the jowl, and the labiomandibular fold. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008; 32:185–195.

45. Mendelson, BC, Hartley, W, Scott, M, et al. Age-related changes of the orbit and midcheek and the implications for facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007; 31:419–423.

46. Millard, DR, Pigott, R, Hedo, A. Submental lipectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 41:513.

47. Miller, T. Face lift: Which technique? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:501.

48. Mitz, V, Peyronie, M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976; 58:80–88.

49. Moss, JC, Mendelson, BC, Taylor, GI. Surgical anatomy of the ligamentous attachments in the temple and periorbital regions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:1475–1490.

50. Nahai, F, Neck lift. The art of aesthetic surgery: Principles and techniques. Nahai, F, eds. The art of aesthetic surgery: Principles and techniques; Vol II. Quality Medical Publishing Inc, St Louis, MO, 2005:1239–1283.

51. Pessa, JE. The tear trough and lid/cheek junction: Anatomy and implications for surgical correction. Plast Reconst Surg. 2009; 123:1332–1340.

52. Pessa, JE. An algorithm of facial aging: Verification of Lambros’s theory by three-dimensional stereolithography, with reference to the pathogenesis of midfacial aging, scleral show, and the lateral suborbital trough deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:479–488.

53. Pessa, JE, Chen, Y. Curve analysis of the aging orbital aperture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002; 109:751–755.

54. Pessa, JE, Desvigne, LD, Zadoo, VP. The effect of skeletal remodeling on the nasal profile: Considerations for rhinoplasty in the older patient. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999; 23:239–242.

55. Pessa, JE, Slice, DE, Hanz, KR, et al. Aging and the shape of the mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121:196–200.

56. Pessa, JE, Zadoo, VP, Mutimer, KL, et al. Relative maxillary retrusion as a natural consequence of aging: Combining skeletal and soft-tissue changes into an integrated model of midfacial aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:205–212.

57. Pessa, JE, Zadoo, VP, Yuan, C, et al. Concertina effect and facial aging: Nonlinear aspects of youthfulness and skeletal remodeling, and why, perhaps, infants have jowls. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 103:635–644.

58. Pitman, G, Aston, SJ, Feldman, JJ, LaFerriere, K. Panel discussion: Revisional neck surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2007; 27:527–538.

59. Pontes, R. Extended dissection of the mental area in face-lift operations. Ann Plast Surg. 1991; 27:439.

60. Rabe, JH, Mamelak, AJ, McElgunn, PJ, et al. Photoaging: Mechanisms and repair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006; 55:1–19.

61. Ramirez, OM. Cervicoplasty: Nonexcisional anterior approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99:1576–1585.

62. Raskin, E, LaTrenta, GS. Why do we age in our cheeks? Aesthet Surg J. 2007; 27:19–28.

63. Reece, EM, Pessa, JE, Rohrich, RJ. The mandibular septum: anatomical observations of the jowls in aging—implications for facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121:1414–1420.

64. Richard, MJ, Morris, C, Deen, B, et al. Analysis of the anatomic changes of the aging facial skeleton using computer-assisted tomography. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 25:382–386.

65. Rohrich, RJ, Arbique, GM, Wong, C, et al. The anatomy of suborbicularis fat: implications for periorbital rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 124:946–951.

66. Rohrich, RJ, Pessa, JE. The fat compartments of the face: Anatomy and clinical implications for cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 119:2219–2227.

67. Rohrich, RJ, Pessa, JE. The anatomy and clinical implications of perioral submuscular fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 124:266–271.

68. Rohrich, RJ, Pessa, JE, Ristow, B. The youthful cheek and the deep medial fat compartment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121:2107–2112.

69. Rosen, HM. Facial skeletal expansion: Treatment strategies and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 89:798–808.

70. Sandoval, S, Cox, J, Koshy, J, et al. Facial fat compartments: A guide to filler placement. Semin Plast Surg. 2009; 23:283–287.

71. Sarver, DM, Rousso, DR. Plastic surgery combined with orthodontic and orthognathic procedures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004; 126:305–307.

72. Schaverien, MV, Pessa, JE, Rohrich, RJ. Vascularized membranes determine the anatomical boundaries of the subcutaneous fat compartments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 123:695–700.

73. Sharabi, S, Hatef, D, Koshy, J. Mechanotransduction: The missing link in the facial aging puzzle? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010; 34:603–611.

74. Shaw, RB, Katzel, EB, Koltz, PF, et al. Aging of the mandible and its aesthetic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 125:332–342.

75. Shaw, RB, Jr., Kahn, DM. Aging of the midface bony elements: A three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 119:675–681.

76. Singer, DP, Sullivan, PK. Submandibular gland I: an anatomic evaluation and surgical approach to submandibular gland resection for facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 112:1150–1154.

77. Singer, DP, Sullivan, PK. Submandibular gland I: An anatomic evaluation and surgical approach to submandibular gland resection for facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 112:1150–1154.

78. Stuzin, JM. Restoring facial shape in face lifting: The role of skeletal support in facial analysis and midface soft tissue repositioning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 119:362–376.

79. Stuzin, JM, Baker, DC, Feldman, J, Marten, TJ. Panel discussion: Cervical contouring in facelift. Aesthet Surg J. 2002; 22:541–548.

80. Stuzin, JM, Baker, TJ, Gordon, HL. The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: Relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 89:441–451.

81. Stuzin, JM, Wagstrom, L, Kawamoto, HK, et al. The anatomy and clinical implications of the buccal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 85:29–37.

82. Sullivan, PK, Freeman, MB, Schmidt, S. Contouring the aging neck with submandibular gland suspension. Aesthet Surg J. 2006; 26:465–471.

83. Teimourian, B. Face and neck suction-assisted lipectomy associated with rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983; 72:627.

84. Wang, F, Garza, LA, Kang, S, et al. In vivo stimulation of de novo collagen production caused by cross-linked hyaluronic acid dermal filler injections in photodamaged human skin. Arch Dermatol. 2007; 143:155–163.

85. Yaar, M, Gilchrest, BA. Skin aging: Postulated mechanisms and consequent changes in structure and function. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001; 17:617–630.

86. Yaremchuk, MJ. Mandibular augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:697–706.

87. Yaremchuk, MJ. Infraorbital rim augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001; 107:1585–1592.

88. Yaremchuk, MJ. Making concave faces convex. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005; 29:141–147.

89. Yaremchuk, MJ. Indications, evaluation and planning. In: Yaremchuk MJ, ed. Atlas of Facial Implants. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2007:3–22.

90. Yaremchuk, MJ, Chen, YC. Enlarging the deficient mandible. Aesthet Surg J. 2007; 27:539–550.

91. Yaremchuck, M, Doumit, G, Thomas, MA. Alloplastic augmentation of the facial skeleton: An occasional adjunct or alternative to orthognathic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127:2021–2030.

92. Yaremchuk, MJ, Israeli, D. Paranasal implants for correction of midface concavity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:1676–1684.

93. Zadoo, VP, Pessa, JE. Biological arches and changes to the curvilinear form of the aging maxilla. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:460–466.

94. Zins, JE, Fardo, D. The “anterior-only” approach to neck rejuvenation: An alternative to face lift surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 115:1761–1768.

95. Zins, JE, Menon, N. Anterior approach to neck rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2010; 30:477–484.