Aesthetic Alteration of the Chin

Evaluation and Surgery

Hugo Obwegeser introduced the intraoral approach to completing an osseous genioplasty in 1957.74 More than half a century later, this relatively simple technique still remains underused when surgeons are asked to make cosmetic changes to the chins of their patients.

Anatomy of the Chin

The word chin describes a region of the face that includes both soft tissue and bone.79,125 The soft-tissue portion encompasses the labial mental fold superiorly, the oral commissures laterally (just anterior to the jowls), and the submental–cervical crease inferiorly. The bony portion of the chin encompasses the mandibular symphyseal region. It includes the region inferior to the root apices of the anterior teeth and the area in front of and below the mental foramen on each side. Within the soft tissues of the chin are found a series of paired muscles that include the mentalis, the quadratis labii inferioris, the triangularis, and the superior portions of the platysma that extend over the symphysis region.22 Attached to the genial tubercle of the chin posteriorly are the tendinous attachments of the geniohyoid and genioglossus muscles.66 The anterior bellies of the digastric muscles are attached to the posterior portion of the inferior border of the symphysis. The sensory innervation to the cutaneous chin, the lower lip, and the inner vestibule is derived from the mental nerve on each side. The motor innervation to the muscles within the soft tissues of the chin occurs through the marginal mandibular and cervical branches of the facial nerve.

Aesthetics of the Chin

In Western society, a “weak” or deficient chin is associated with timidity, indecision, femininity, a lack of athleticism, and shy behavior. Conversely, a “strong” or forwardly projecting chin is associated with athleticism, aggressiveness, decisiveness, and bold behavior. The fact that an average adult from any number of ethnic backgrounds and nationalities from around the world will frequently characterize a chin as either “weak” or “strong” demonstrates the subliminal messages communicated about the character of a person as a result of the presenting chin morphology. When people speak about chin contour, emphasis is generally placed on the profile view (Fig. 37-1).2,13,90,91 Although it is true that a retrusive pogonion is a frequently mentioned concern, the chin may also be asymmetric or out of the normal range in more than one dimension.

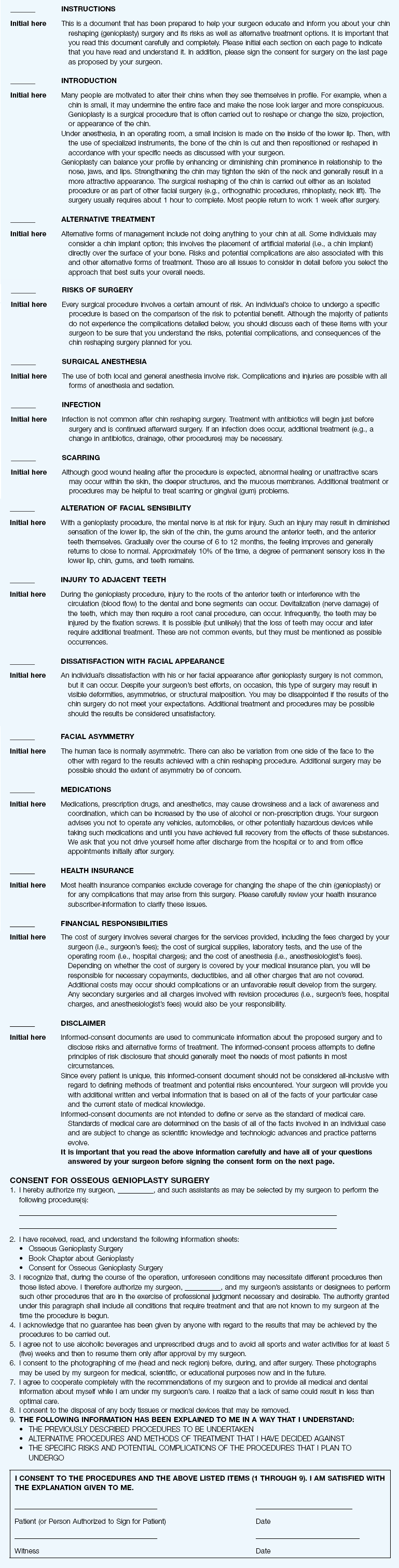

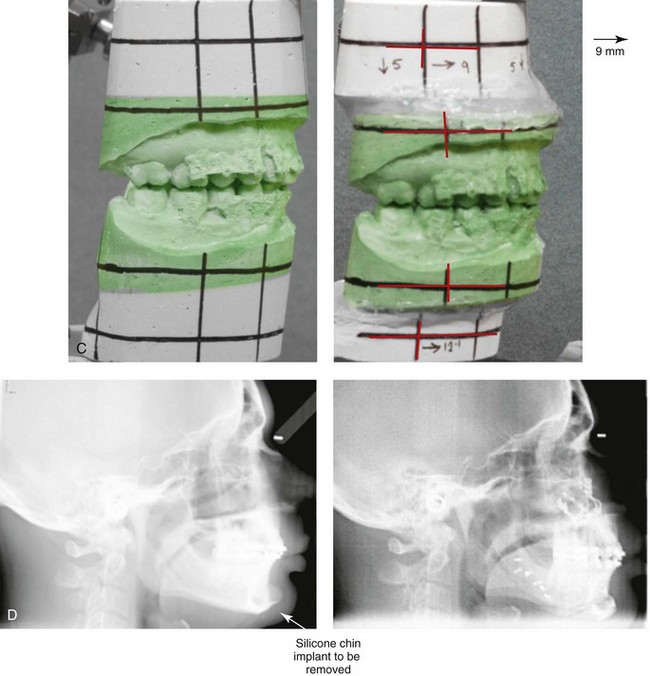

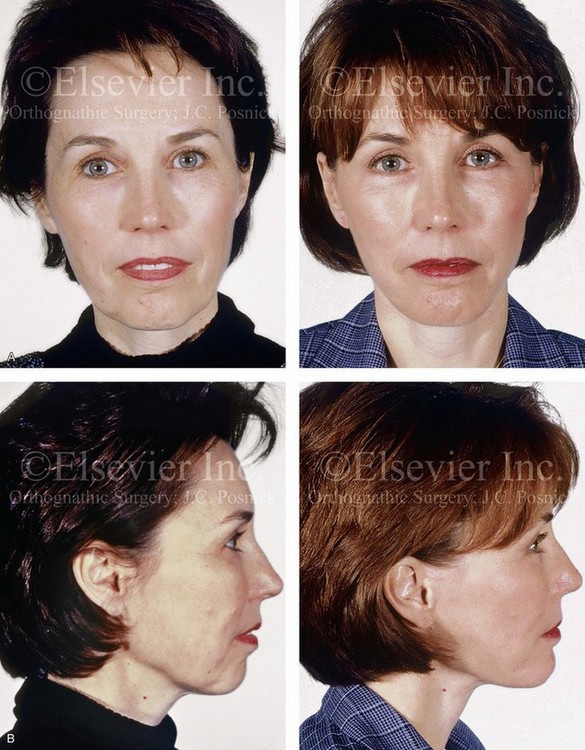

Figure 37-1 A 29-year-old woman arrived to discuss her chin aesthetics. During the mixed dentition, she was recognized as having mandibular deficiency and a constricted maxillary arch width. At that time, she underwent growth-modification techniques, including the use of headgear. She also underwent rapid palatal expansion followed by compensatory orthodontic mechanics to neutralize the occlusion, but this resulted in proclination of the incisors. A retrusive profile and a dual bite remained. She recently underwent the placement of an extended silastic chin implant but without fixation by another surgeon. Aesthetic modification of the anterior maxillary dentition was also completed by a restorative dentist. She is displeased with the cosmetic facial results of a deepened labiomental fold, a mobile chin implant, and a “button” appearance during lip closure. There is a dual bite with Class II malocclusion in centric relation. A, Oblique and frontal facial views after chin implant placement. B, Profile facial view and lateral cephalometric radiograph 6 months after chin implant placement.

When it is taken with the patient in the natural head position, with the lips relaxed (i.e., in repose) and with the lower jaw at rest (i.e., the condyles seated in the fossa and with a normal freeway space between the teeth), a lateral cephalometric radiograph provides an accurate image of the facial skeleton and the overlying soft tissues from which to judge profile aesthetics.28,30,31,43,44,83,105,112 When viewing either a full-face lateral photograph or a soft-tissue lateral cephalometric radiograph taken in this way, a vertical line (i.e., perpendicular to the floor with the patient in the natural head position) can be drawn through the subnasal region to assess the relative prominence of the nose, lips, and chin.36 Ideally, the chin should lie on this line, with the lips slightly anterior (Figs. 37-2 through 37-5).9 It is also true that there are many complex interrelationships among the facial structures that should be taken into consideration.1–3,51,52,60,69,95,118 Critical decisions with regard to where to position the chin through osseous genioplasty are made when viewing the patient “face to face” from varying perspectives in repose and during broad smile in the clinic setting.4,16,124,126

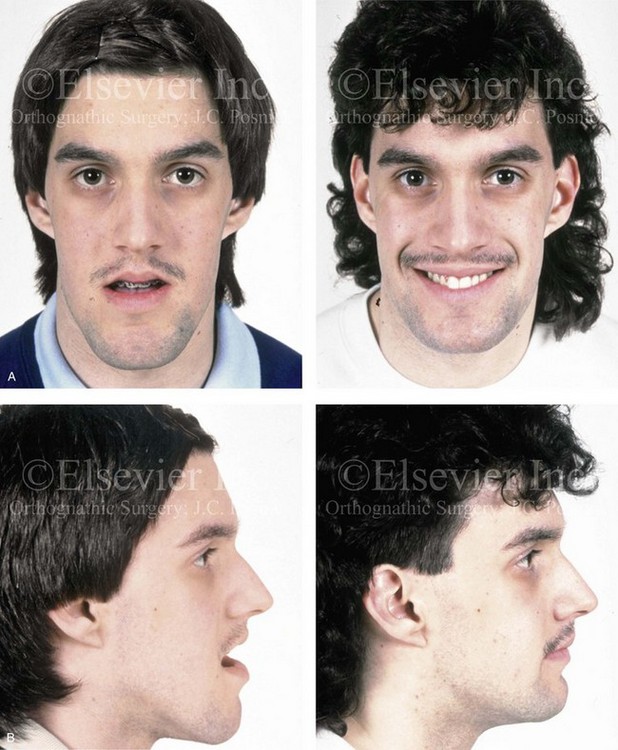

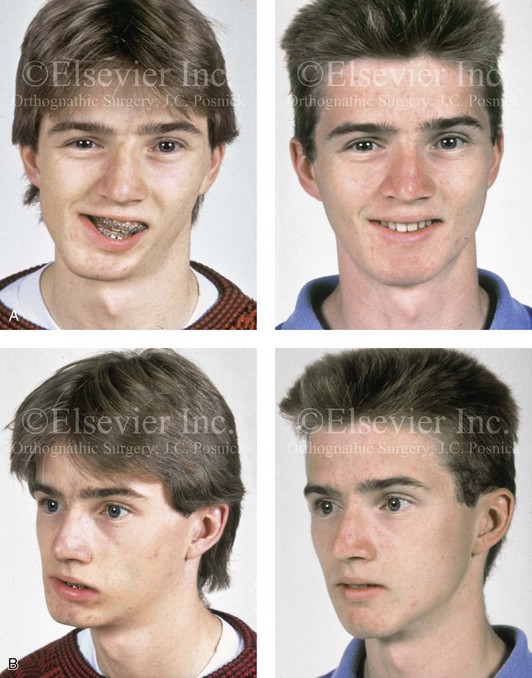

Figure 37-2 A 17-year-old boy arrived with his father for the evaluation of a “weak chin” and requested chin augmentation. He had undergone orthodontic treatment with the establishment of a satisfactory occlusion that required minimal dental compensation. He agreed to undergo osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement) to resolve the chief complaint. A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Figure 37-3 A 16-year-old girl arrived with her mother and requested a cosmetic rhinoplasty to reduce the dorsal hump and to improve the drooped nasal tip seen in profile. She also had a lifelong history of nasal obstruction. Evaluation confirmed the aesthetic nasal needs as well as sagittal deficiency of the chin. She agreed to undergo septorhinoplasty and osseous genioplasty. The rhinoplasty included nasal osteotomies (in-fracture); dorsal reduction (bone and cartilage) and tip maneuvers (modification of lower lateral cartilages and septal cartilage caudal strut grafting); septoplasty; and the reduction of the inferior turbinates. Osseous genioplasty included horizontal advancement. A, Profile facial views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction.

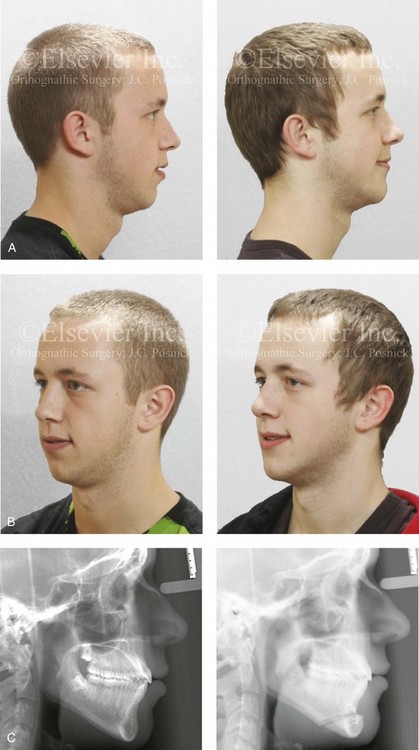

Figure 37-4 A 17-year-old girl arrived with her mother and requested a cosmetic rhinoplasty to reduce the dorsal hump and to improve the drooped nasal tip seen in profile. She also had a lifelong history of nasal obstruction. Evaluation confirmed the aesthetic nasal needs as well as sagittal and vertical deficiency of the chin. She agreed to undergo septorhinoplasty and osseous genioplasty. The rhinoplasty include nasal osteotomies (in-fracture); dorsal reduction (bone and cartilage) and tip maneuvers (modification of lower lateral cartilages and septal cartilage caudal strut grafting); septoplasty; and the reduction of the inferior turbinates. Osseous genioplasty included horizontal advancement and vertical lengthening with interpositional grafting (bloc hydroxyapatite). A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

Figure 37-5 An 18-year-old girl arrived with her parents and requested a cosmetic rhinoplasty and a chin implant. She hoped for a smaller nose, a reduction of the dorsal hump, and a stronger profile. She also had a history of nasal obstruction after a sports injury earlier during her life. Examination confirmed mild sagittal deficiency of the mandible but with a functional occlusion and minimal dental compensation after earlier orthodontic treatment. She agreed to undergo septorhinoplasty and osseous genioplasty. The patient’s nasal procedures included nasal osteotomies (in-fracture); dorsal reduction (bone and cartilage); tip maneuvers (modification of lower lateral cartilages and septal cartilage caudal strut grafting); septoplasty; the reduction of the inferior turbinates; and osseous genioplasty with horizontal advancement. A, Frontal views in repose before and 8 years after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and 8 years after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and 8 years after reconstruction. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and 8 years after reconstruction.

Biologic Foundation of Osseous Genioplasty

When carrying out an osseous genioplasty, a horizontal osteotomy below the roots of the anterior teeth and the mental foramen on either side is completed. After osteotomy, the distal segment of the chin remains attached to a musculoperiosteal pedicle. Healing is optimal when the circulation of blood to bone and its enveloping soft tissue is continuously maintained. In 1988, Bell and colleagues completed microangiographic and histologic studies in adult rhesus monkeys that indicated that an intraoral pedicled flap that involved an osteotomy of the inferior mandibular border maintains circulation and osseous viability after manipulation and repositioning of the chin segment.106 According to Bell’s experimental work, circulation to the dental pulp should not be discernibly affected during the process.

Frequent Patterns of Chin Deformities

Horizontal Chin Deficiency with or without Vertical Discrepancy

Contemporary maxillofacial surgeons now recognize that individuals who are seeking a “stronger chin” (i.e., horizontal projection) frequently also have disproportions in the vertical dimension of their face.23,33,45,59,61,77,88,89,92,116,120,123,127,131 Studies suggest that approximately 40% of individuals with horizontal (sagittal) chin deficiency have a decreased lower anterior facial height (i.e., short face growth pattern) (Figs. 37-4, 37-6, and 37-7). It is also known that another 25% of these will have the other extreme of an increased lower anterior facial height (i.e., long face growth pattern) (Figs. 37-8 through 37-11). In either case, the bony chin dysmorphology will also result in soft-tissue abnormalities (distortions) of the labiomental fold. This often includes a deep labiomental angle in those with a short face growth pattern and a flat labiomental fold in those with a long face growth pattern. Fifty percent of individuals with a horizontally deficient chin will have an Angle class II malocclusion, which is indicative of mandibular retrusion. Forty percent will have previously undergone orthodontic camouflage treatment in an attempt to mask their micrognathia (see Fig. 37-1). Incisor flaring will have resulted from the orthodontic camouflage approach that attempted to neutralize a Class II excess overjet malocclusion as an alternative to a more biologic correction of the mandibular deficiency through orthognathic surgery. Some of these individuals will have also undergone chin implant augmentation, often with a suboptimal result (see Fig. 37-1, 37-7, and 37-9).

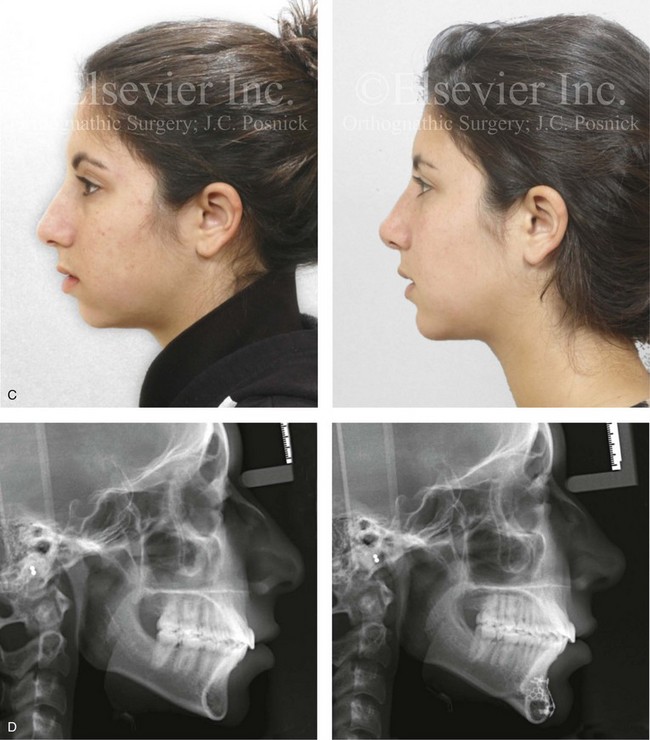

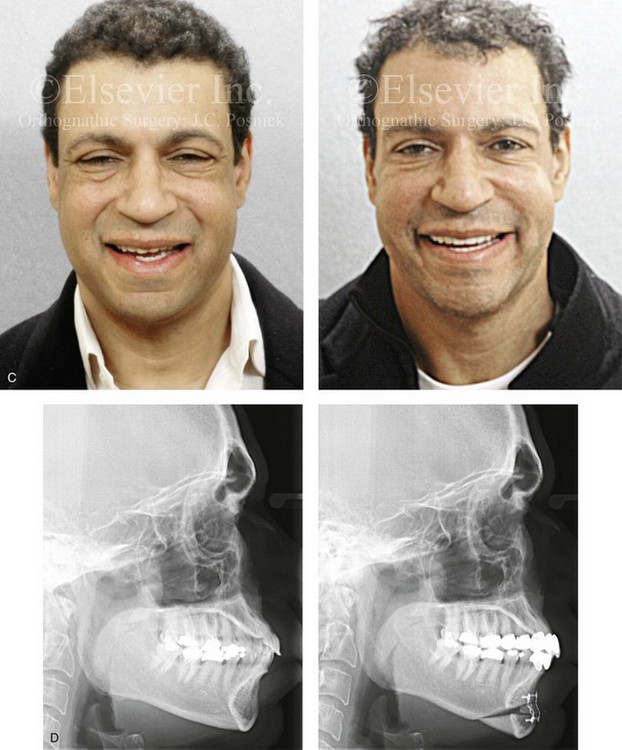

Figure 37-6 A 24-year-old woman arrived for evaluation. She had previously undergone four bicuspid extractions and orthodontics to neutralize her occlusion during her high school years. Analysis confirmed a short face growth pattern that accounted for her apparent large nose, weak profile, obtuse neck chin angle, and edentulous look. She agreed to a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting; sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and minimal horizontal advancement) with interpositional grafting. Minimal change in the occlusion was required (see Fig 23-3). A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. C, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic surgical planning. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

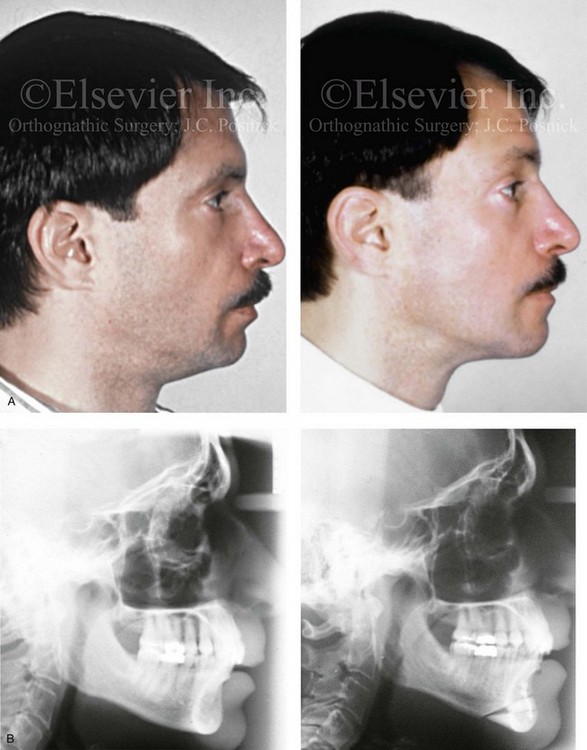

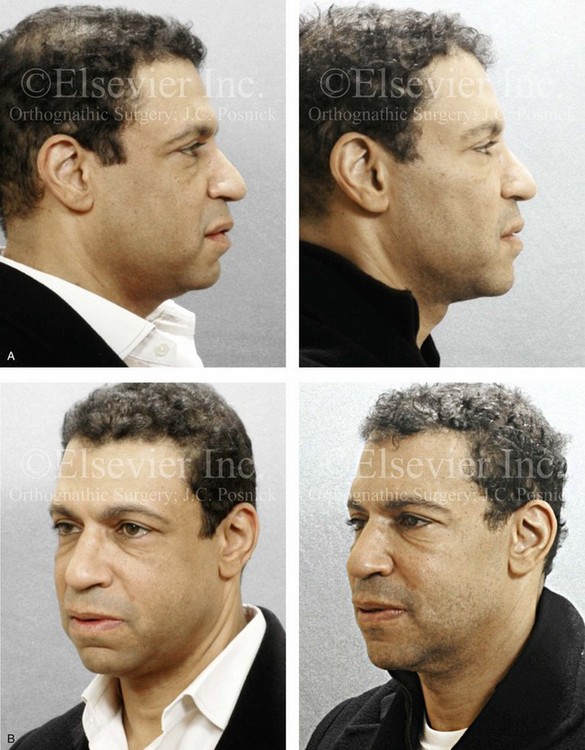

Figure 37-7 A 37-year-old man was referred with a request to have a chin implant removed because he was displeased with the aesthetic results. When he was 20 years old, he underwent chin augmentation with a silicone implant in an attempt to camouflage his small lower jaw profile. Ten years later, he underwent four bicuspid extractions and orthodontic alignment to improve his occlusion. He had also undergone a septorhinoplasty procedure, but he was still experiencing continued difficulty breathing through the nose. During evaluation by this surgeon, he was recognized as having a short face growth pattern with decreased lower anterior facial height and limited facial projection. There was an accentuated labiomental lip curl and a “button” appearance to the chin. It became clear during a discussion that the patient suffered with snoring, restless sleeping, and excessive daytime fatigue. An attended polysomnogram confirmed a respiratory disturbance index of 16 events/hr, with desaturations of up to 89%. A titration study confirmed the need for 12 cm of water pressure to reduce the respiratory disturbance index to 3 events/hr. The use of continuous positive airway pressure was attempted but found to be uncomfortable and difficult for the patient to use. A, Frontal views with smile before and after surgery. B, Profile views before and after surgery. Consultations with a sleep specialist, an otolaryngologist, and an orthodontist confirmed the advantage of an intranasal and orthognathic surgical approach. The patient agreed to perioperative orthodontics and surgery to improve the airway and facial appearance. His procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement +9 mm, vertical lengthening +5 mm), with interpositional grafting; bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal advancement +12 mm); removal of the chin implant; osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement and vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting; reduction of the inferior turbinates; redo septoplasty; and an anterior approach to the neck (cervical flap elevation, defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication). As a result of the procedures, the patient experienced relief of his snoring, improved quality of sleep, diminished daytime fatigue, and improved breathing during the day. Six months after surgery, he underwent an attended polysomnogram that indicated a normal sleep study with no snoring or apnea events (see Fig. 26-10). C, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic surgical planning. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery (note the preoperative chin implant).

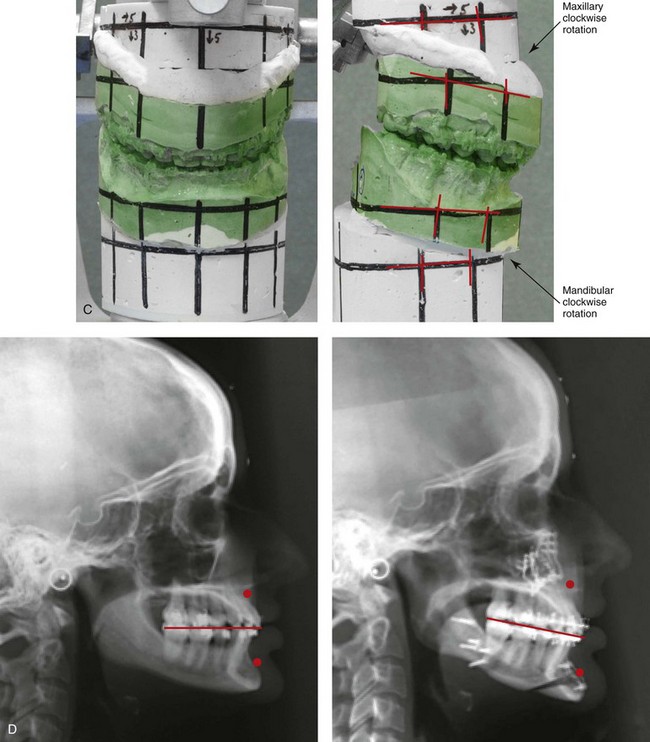

Figure 37-8 A 21-year-old college graduate arrived for surgical evaluation. Her history and physical examination confirmed lifelong nasal obstruction, lip incompetence, difficulty chewing, and frequent speech articulation errors. Facial aesthetic concerns include a weak chin, a gummy smile, lip strain, and the impression of having a “big nose.” The patient had been under an orthodontist’s care since the mixed dentition and through her high school years. Growth modification attempts followed by rapid palatal expansion and full bracketing with four bicuspid extractions were unsuccessful to close the anterior open bite. Early periodontal and dental deteriorization were evident. Further evaluations were carried out by a speech pathologist, an otolaryngologist, and a periodontist; in addition, a fresh look was taken at this patient’s orthodontic needs. Orthodontic dental decompensation in combination with orthognathic and intranasal surgery was chosen. The simultaneous procedures that were carried out included Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, counterclockwise rotation, arch expansion, and correction of the curve of Spee); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring (see Fig. 21-5). A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Profile views before and after reconstruction. C, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

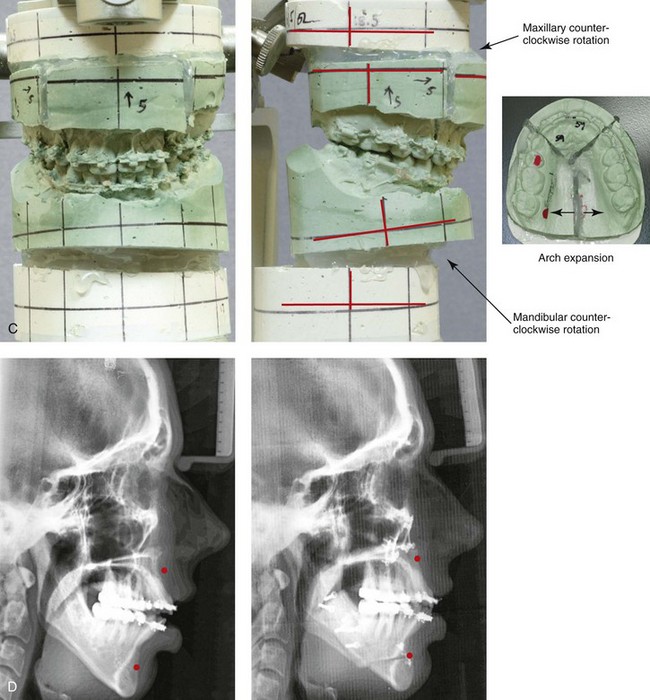

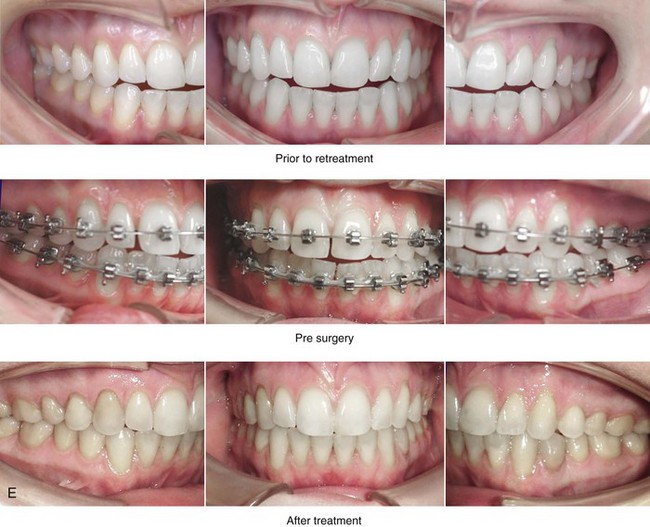

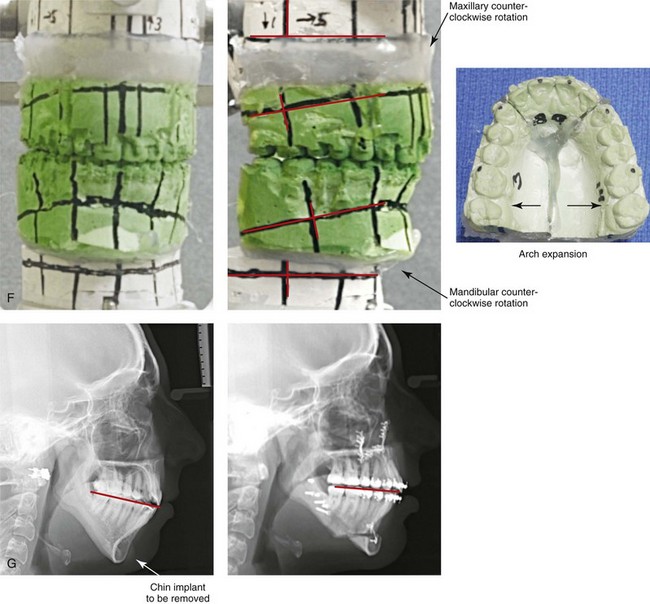

Figure 37-9 A 21-year-old college graduate arrived for surgical evaluation. Her history and physical examination confirmed lifelong nasal obstruction, heavy snoring, lip incompetence, difficulty chewing, and frequent speech articulation errors. Facial aesthetic concerns included a weak chin, a gummy smile, and the impression of having a “big nose.” She had been under an orthodontist’s care from the mixed dentition through her high school years. Growth modification followed by rapid palatal expansion and full bracketing with attempted closure of the anterior open bite were attempted, without success. She had undergone a chin implant in an attempt to improve the profile, but this was also suboptimal. Further evaluations were carried out by a speech pathologist and an otolaryngologist, and a fresh look was taken at this patient’s occlusal/dental needs. Orthodontic decompensation in combination with orthognathic and intranasal surgery was chosen. The simultaneous procedures that were carried out included Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, counterclockwise rotation, arch expansion, and correction of the curve of Spee); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); removal of the chin implant; osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontic decompensation in progress, and after the completion of treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery. Note that the chin implant was inadequate to improve the profile. An osseous genioplasty in addition to an orthognathic correction achieved the chosen objectives.

Figure 37-10 Intraoperative views of four silicon/Silastic chin implants removed from four separate patients who had suffered complications and suboptimal results and who had requested chin implant removal.

Figure 37-11 A woman in her early 50s with facial aging concerns. She had a mild long face growth pattern and a satisfactory occlusion. The lower anterior facial height was increased, which resulted in mild lip incompetence and mentalis strain as well as deep perioral creases. She agreed to blepharoplasty (elliptical excision of upper lid skin and redraping of lower lid tissue); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and a face lift (see Fig. 40-9). A, Frontal views before and after surgery. B, Profile views before and after surgery. Note the relief of the perioral folds and mentalis strain as a result of vertical reduction and advancement genioplasty.

A pleasing labiomental fold is an essential component of optimal lower face aesthetics. A strong correlation exists between the lower anterior facial height and the labiomental fold morphology. Individuals with decreased lower anterior facial height in combination with a retrusive-appearing chin tend to have an exaggerated and excessively deep labiomental fold with acute angulation between the lower lip and the soft-tissue chin pad (i.e. primary mandibular deficiency or maxillomandibular deficiency; see Figs. 37-4, 37-6, and 37-7). Individuals with increased lower anterior facial height in combination with a horizontally deficient chin are likely to have a labiomental fold that is flattened and effaced, with poor fold definition, excess mentalis strain, and difficult lip closure (i.e., long face growth pattern). The long face growth pattern classically consists of vertical excess of the maxillary and mandibular alveolar regions. This is combined with mandibular retrognathia and an anterior open-bite Class II malocclusion (see Figs. 37-8 and 37-9).

Rosen and others have pointed out that many individuals with mandibular deficiency and decreased lower anterior facial height who have a functional occlusion are unwilling to undergo an orthognathic correction and may opt for a compromise approach to at least achieve some aesthetic advantage (Figs. 37-12 through 37-17).88–93An osseous genioplasty to simultaneously vertically lengthen and horizontally advance the chin will generally achieve a degree of improved lower facial height and chin projection while reducing the deep labiomental fold. When this compromise is undertaken, no improvement in any baseline malocclusion or any significant opening of the airway should be expected. From an aesthetic perspective, it is essential to prevent an operated look when choosing a chin-only approach. This aesthetic error can be limited by avoiding the temptation to fully correct a moderate to severe mandibular deficiency through an isolated chin procedure (see Figs. 37-13 and 37-15).

Figure 37-12 A Caucasian man in his 30s arrived for the evaluation a “weak chin” and requested aesthetic improvement. Examination confirmed a mild developmental mandibular deficiency (see Chapter 19). Successful orthodontics had been carried out during his teenage years, with only mild flaring of the mandibular incisors. An osseous genioplasty was agreed to that included significant vertical lengthening and limited horizontal advancement with interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting. A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. B, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

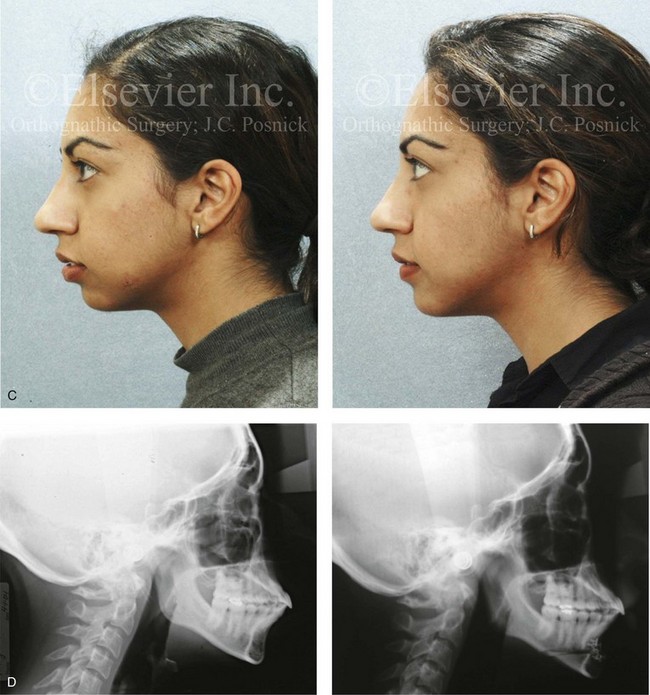

Figure 37-13 A 27-year-old Indian woman arrived and requested of a reduction rhinoplasty and a chin implant to treat her perceived “big nose” and “small chin.” Analysis confirmed maxillomandibular sagittal deficiency that was treated during her teenage years with compensatory orthodontics to neutralize the occlusion. There was marked procumbency of the maxillary and mandibular anterior dentition but with adequate tooth and gingival show, without lip incompetence and with good to the periodontium. The nasal aesthetic unit had thick skin but satisfactory proportions. The patient lacked lower anterior facial height and facial projection, especially at the pogonion. She was treated with an osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and limited horizontal advancement) and interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting. A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Figure 37-14 A woman in her early 20s arrived for the evaluation of her facial aesthetics. She had a developmental jaw deformity that was characterized primarily by mandibular deficiency and a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. During her teenage years, she underwent an orthodontic camouflage approach that included maxillary bicuspid extractions with anterior dentition retraction to achieve an improved occlusion. She perceived a “big nose” and a “small chin” and requested reduction rhinoplasty and a chin implant. She refused redo orthodontics and an orthognathic correction (see Chapter 19). A compromise was agreed to that included open rhinoplasty and osseous genioplasty. The patient’s rhinoplasty included nasal osteotomies (in-fracture and straightening); dorsal reduction (bone and cartilage); and tip maneuvers (modification of lower lateral cartilages and septal cartilage caudal strut grafting). Osseous genioplasty included vertical lengthening with interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting and minimal horizontal advancement. A, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

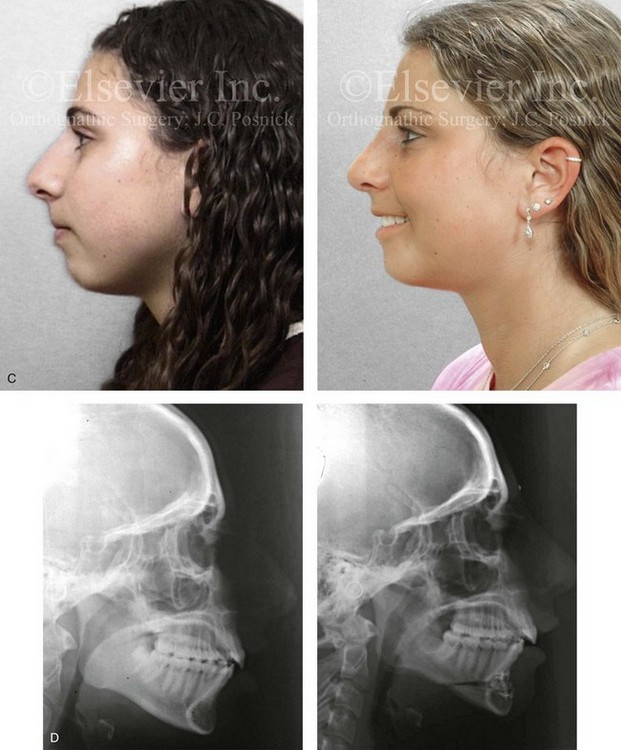

Figure 37-15 A woman in her mid 20s arrived for the evaluation of her facial aesthetics. She had a short face growth pattern (i.e., maxillomandibular deficiency) that was treated during her teenage years with compensatory orthodontic alignment only. An orthognathic correction to improve her horizontal facial projection and to increase the lower anterior facial height was recommended (see Chapter 23). She was unwilling to undergo further orthodontics and refused an orthognathic approach. A compromise was agreed to that included open rhinoplasty and osseous genioplasty. The patient’s rhinoplasty included nasal osteotomies (in-fracture and straightening); dorsal reduction (bone and cartilage); and tip maneuvers (modification of lower lateral cartilages and septal cartilage caudal strut grafting). Osseous genioplasty included vertical lengthening and minimal horizontal advancement with interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

Figure 37-16 A woman in her early 50s requested an evaluation of a “weak chin,” deep perioral creases, mild ptosis of the brow and upper eyelids, and unfavorable nasal aesthetics. Examination confirmed mild drooping of the brow and mild excess skin of the upper eyelids. A developmental mandibular deficiency was unchanged over the years, and she had a functional occlusion. She agreed to a limited incision brow lift, but as a result of dryness of the eyes, decided against the removal of the skin of the upper lid. She also agreed to an osseous genioplasty that included vertical lengthening and horizontal advancement with interpositional bloc hydroxyapatite grafting. Her rhinoplasty included nasal osteotomies (in-fracture); dorsal reduction (bone and cartilage); and tip maneuvers (modification of lower lateral cartilages and septal cartilage caudal strut grafting). All procedures were carried out simultaneously. A, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. B, Profile views before and after surgery.

Figure 37-17 An African-American man in his early 40s underwent evaluation for a “weak chin” and laxity of the neck soft tissues. There was a degree of procumbency to the maxillary and mandibular dentition but with a stable occlusion. He also planned to undergo cosmetic modification of the anterior dentition. A treatment plan was agreed to that included osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening with interpositional grafting and minimal horizontal advancement) and an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication). A, Profile views before and after surgery. B, Oblique facial views before and after surgery. C, Frontal views before and after surgery. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

In the individual with a functional occlusion, a retrusive chin and an increased lower anterior facial height (i.e., long face growth pattern), the surgical camouflage approach will be different than what is used for the patient with a short face growth pattern, as described previously. As an aesthetic compromise, it will be an advantage to vertically shorten and horizontally advance the chin (see Fig. 40-9). This will at least marginally decrease the mentalis strain to improve the ease of lip closure and also to enhance the appearance of the lower face (see Fig. 37-11).

Horizontal Chin Prominence and Associated Vertical Discrepancy

Individuals who present with a prominent pogonion are likely to have disproportions of the lower anterior facial height (i.e., the vertical dimension), which in turn affect labiomental fold morphology.6,64,99,135 When an individual presents with a prominent pogonion and asks for a chin reduction only, he or she will likely not be pleased with the aesthetic result if this limited request is honored.

A commonly seen pattern of jaw deformity is maxillary deficiency in combination with relative mandibular excess (i.e., skeletal Class III growth pattern; see Chapter 20). This often presents in association with a vertically long (i.e., as measured in millimeters from the mandibular incisor edge to the menton height) and protrusive (i.e. forwardly projected) chin (Fig. 37-18). These individuals generally benefit from Le Fort I advancement with or without simultaneous vertical lengthening and clockwise rotation. Mandibular ramus osteotomies are also carried out with limited or no set-back at the incisors but with clockwise rotation to diminish projection at the pogonion. In this case, lower-face aesthetics are often further enhanced via an osseous genioplasty with vertical reduction and minimal sagittal change.

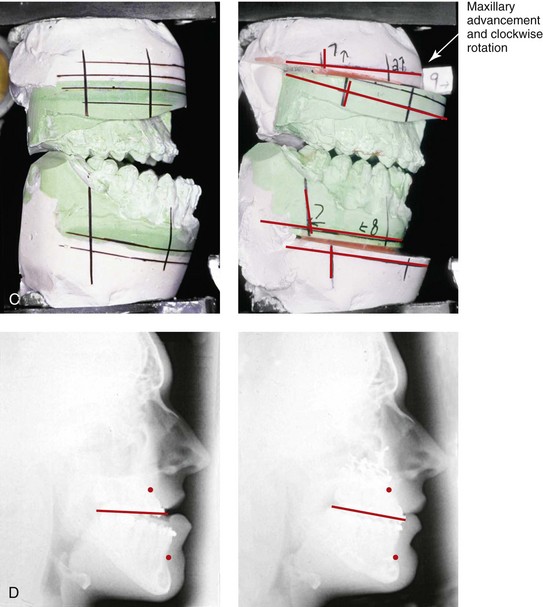

Figure 37-18 A 17-year-old high school student was referred by his orthodontist for surgical evaluation. His maxillary deficiency and mandibular excess Class III negative overjet anterior open-bite malocclusion required orthodontics and jaw surgery. Because the patient had a lifelong history of nasal obstruction and consistent physical findings, intranasal procedures were also required. With orthodontic dental decompensation complete, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, anterior vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (set-back); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views before and after treatment. B, Profile views before and after treatment. C, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. D, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

A second frequent pattern of presentation is an individual with a chin that appears prominent in profile because the mandible is overly closed (i.e., short face growth pattern). In these patients, the vertical height (in millimeters) from the mandibular incisal edges to the menton is deficient. With this dentofacial deformity, both horizontal and vertical deficiency of the maxilla and the mandible (i.e., decreased lower anterior facial height and limited facial projection) are present (see Chapter 23). A “pseudoprotrusion” of the chin will result. A patient who asks for a chin set-back only to manage his or her short face (i.e., maxillomandibular deficiency) is unlikely to be pleased with the aesthetic result if this request is honored. In this case, reestablishing the preferred vertical and horizontal dimensions of the face requires a Le Fort I osteotomy with horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and, often, clockwise rotation. The mandible—which is also horizontally and vertically deficient—requires sagittal split ramus osteotomies and reorientation to match the new maxillary position. The chin region also benefits from a change in shape. This is accomplished through an oblique osteotomy of the chin with clockwise rotation (i.e., downward and backward positioning of the pogonion) while maintaining contact and pivoting at the posterior osteotomy line. The interpositional gap is grafted with allograft, autograft, or bone substitute, and the chin segment is fixed in place with plates and screws (see Figs. 37-6 and 37-7).

Chin Asymmetries

Asymmetries of the chin relative to the face are most frequently encountered in association with specific syndromes and other conditions such as hemifacial microsomia, hemimandibular elongation, hemimandibular hyperplasia, or a condyle fracture sustained during childhood with resultant ipsilateral mandibular undergrowth (Fig. 37-19). For individuals who present with the chin shifted to one side, aesthetic assessment of the entire face, including the soft tissues and the skeletal structures, should be undertaken. Consideration is given to both the lower facial skeleton (i.e., the maxilla, the mandible, and the chin region) and the upper facial skeleton (i.e., the cranial vault, the zygomas, the orbits, and the nasal bones). The chin region may be asymmetric or disproportionate, or it may simply appear to be so as a result of maxillary or mandibular malposition. In several of the conditions mentioned, the extent of actual chin asymmetry is much less than that of the mandible and maxilla. When indicated, a Le Fort I osteotomy and sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible with three-dimensional repositioning will greatly improve the chin symmetry. A separate osteotomy to reposition the chin region is also generally required to simultaneously correct disproportion of the lower third of the face.

Figure 37-19 A 16-year-old boy who had sustained a fracture of the right condyle of the mandible during his early childhood presented with resulting facial asymmetry. He previously underwent years of orthodontics to neutralize the occlusion, which also resulted in loss of labial bone along the anterior mandibular teeth. He then underwent an orthognathic approach that included Le Fort I osteotomy (cant correction); left sagittal split ramus osteotomy; reconstruction of the right condyle–ascending ramus with a costochondral graft; and an osseous genioplasty (correction of vertical and horizontal asymmetry) (see Fig. 35-8). A, Frontal facial views with smile before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. A, from Posnick JC: Management of facial fractures in children and adolescents, Ann Plast Surg 33:442-457, 1994.

Osseous Genioplasty: Surgical Technique

• Attention is turned to the facial vestibule of the chin. The lower lip is stretched outward to allow for visualization of the mental nerve through the mucosa on each side. In the depth of the vestibule, an incision is made with a Bovie electrocautery device or a knife (no. 15 blade) just through the mucosa from cuspid region to cuspid region, stopping just short of the visualized mental nerve on each side (Fig. 37-20, A). The center two thirds of the incision is next extended down to bone. A full cuff of mucosa and muscle is maintained adjacent to the attached gingiva of the anterior teeth; this should allow for adequate layered wound closure of the muscle and mucosa without periodontal sequelae.

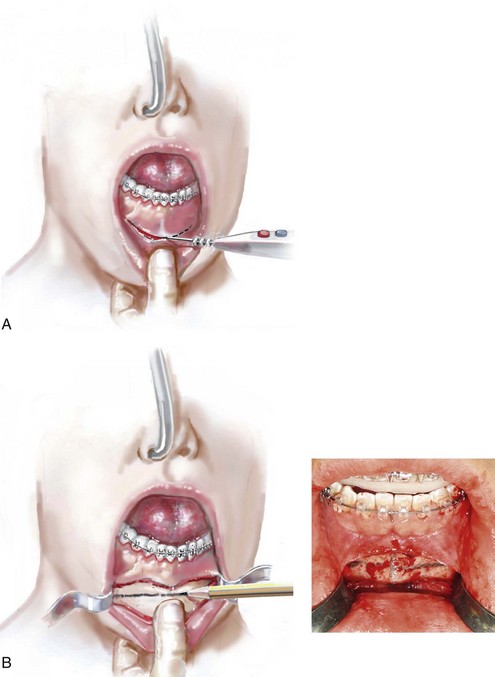

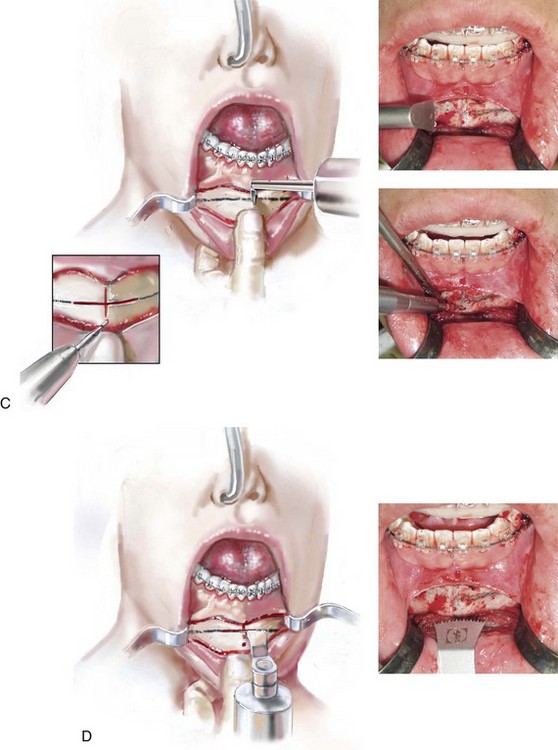

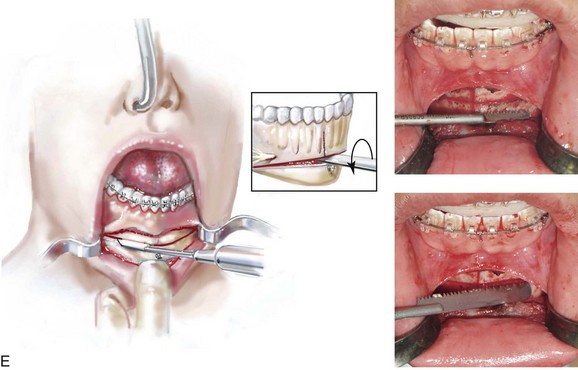

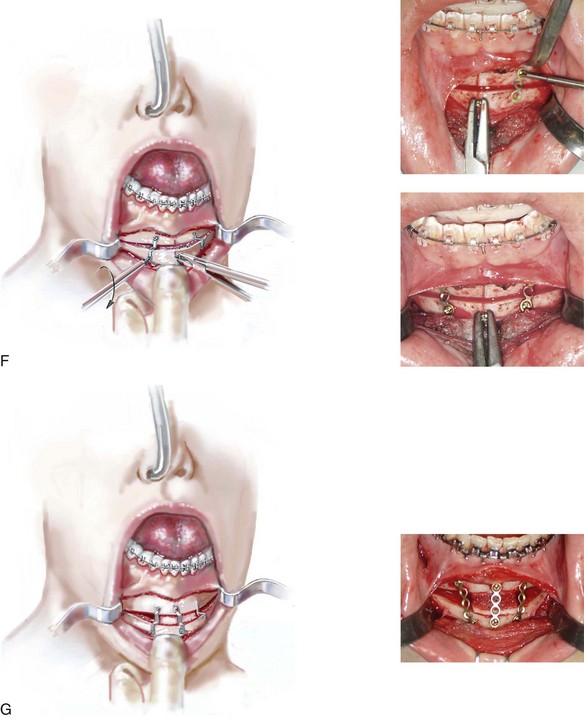

Figure 37-20 Illustrations of standard osseous genioplasty. See the text for descriptions of the techniques depicted.

• Dissection with an elevator exposes the anterior surface of the chin although not completely to the inferior border of the central chin. The dissection continues laterally and remains inferior to the mental nerve, with lateral exposure to the inferior border of the mandible. There is no need to dissect above the mental nerve on either side. If 360-degree dissection around the nerve is completed, it is more likely that the nerve will be excessively stretched or avulsed.

• A small S-shaped Tessier chin retractor is placed on each side inferior to the mental nerve and laterally to the inferior border. A sterile pencil is used to mark the location of the oblique osteotomy ((see Fig. 37-20, B). This should be planned sufficiently below the dental roots and the mental foramen on each side. The exact location of the osteotomy will depend on the presenting chin morphology and the planned reconstruction (i.e., vertical reduction or lengthening and the extent of horizontal advancement).

• With the use of an oscillating saw (i.e., a thin fan blade on a long shaft), a vertical groove is made in the midline across and perpendicular to the proposed horizontal osteotomy. This will help to maintain vertical orientation after the osteotomy and before fixation (see Fig. 37-20, C).

• A drill hole is placed in the midline within the distal chin (see Fig. 37-20, C). Later, a screw (1.7 mm in diameter and 8 mm in length) will be partially inserted and used as a retractor. The screw is usually not placed in the distal chin until the osteotomy is completed. It will then be held with a wire twister that is used as a retractor to facilitate the repositioning and orientation of the distal chin unit.

• The oblique osteotomy of the chin is initiated in the central portion with the use of an oscillating saw (i.e. wide fan blade on a short shaft). The use of this saw and blade to initiate the osteotomy helps to maintain orientation and to limit canting (see Fig. 37-20, D).

• Using a reciprocating saw with a short blade and then with a longer blade is helpful to complete the lateral aspects of the osteotomy and to go through the depth of the bone on each side (see Fig. 37-20, E). An osteotome may be inserted with a twisting motion to complete the osteotomy separation (see Fig. 37-20, E).

• When vertical shortening of the chin is planned, there are two options. If only limited shortening is required in combination with horizontal advancement, it may be preferred to use a rotary drill with a watermelon bur to remove bone height at the osteotomy line. If a more significant vertical reduction is planned, a second parallel osteotomy (for ostectomy) is completed through the proximal chin (below the dental roots) using a reciprocating saw with a straight blade on a long shaft. Any lateral–inferior bony irregularities are also removed using a rotary drill with a watermelon bur to limit palpable or visible step-offs.

• The distal chin is held in the desired position by the assistant to the surgeon with the use of the wire twister secured to the positioning screw. The surgeon contours each titanium plate across the osteotomy site and then secures each with screws (1.7 mm in diameter and 4 mm in length). Typically, either a three- a four-hole straight plate is contoured with the ends placed on either side of the osteotomy. The superior screw is usually placed in between and inferior to the lateral incisor and canine on each side (see Fig. 37-20, F). With the chin secured in its new location, the positioning screw is removed.

• If significant vertical lengthening of the chin is planned, an interpositional graft (e.g., autograft, allograft, bloc hydroxyapatite) is crafted and placed in the gap. The graft fills the central gap between the fixation plates. I do not find it necessary to place graft in the lateral aspect of the gaps. An additional plate and screws are generally placed vertically in the midline across the osteotomy site and directly over the graft (see Chapter 18 and Fig. 37-20, G).

Achieving Favorable Chin Aesthetics

Riolo’s table of normative cephalometric values confirms that the mean vertical height of the chin (i.e., the mandibular incisal edge to the menton) is approximately 42 mm (±2.7 mm) for females and 49.4 mm (±2.9 mm) for males.83A These measurements are a useful benchmark from which to judge the preferred vertical height of the individual’s chin.

Avoiding Pitfalls during Chin Surgery

The chin is one of the most visually prominent facial features, and its role in facial appearance has been recognized since antiquity. It may seem to be an easy structure to alter, but focusing on the chin without fully considering the associated facial dysmorphology (e.g., the skeleton, the dental and soft tissues) may have unexpected and unwanted effects on overall aesthetics. The basic surgical technique of osseous genioplasty is reviewed earlier in this chapter. It is also illustrated in Figure 37-20 and can be seen on (![]() Videos 11 and 12). Avoiding pitfalls during the aesthetic evaluation of the patient’s chin and during the surgical execution of an osseous genioplasty is essential to the achievement of a favorable outcome.*

Videos 11 and 12). Avoiding pitfalls during the aesthetic evaluation of the patient’s chin and during the surgical execution of an osseous genioplasty is essential to the achievement of a favorable outcome.*

1. When assessing a chin that is considered to be either retrusive or protrusive, place the patient in the natural head position and the mandible in the rest position (i.e., with the condyles seated and with normal freeway space between the teeth in each arch). The lips should be relaxed and separated. By assessing the face in this way, you are likely to unmask any baseline dentofacial deformity (e.g., short or long face growth pattern) and to gain a more accurate impression of any true chin disproportion.

2. The experienced surgeon will rely heavily on the direct visual examination to evaluate overall facial proportions and any notable mirror-image asymmetries that involve (but are not limited to) the chin region. Without protractors or rulers, the absence of Euclidean proportions can usually be discerned. Confirmation of the clinician’s aesthetic impressions may then be clarified through either anthropometric surface measurements or cephalometric radiographic analysis, as indicated.

3. The theoretic advantage of an alloplastic (chin implant) genioplasty is that it is a procedure that is seemingly easier to execute and often considered less invasive by the patient. It has the disadvantage of being primarily effective only for a mild anteroposterior deficiency of the chin, and it generally requires an external facial scar. It will have a higher incidence of infection than a chin osteotomy, and such an infection may even occur years later.34,35,41,49,82,121,125 In addition, there may be underlying bony erosion from the implant over time, and the individual can never be without at least some concern about trauma to the chin. Alternatively, the osseous genioplasty is versatile in all three planes and has proven and long-lasting results without concerns about infection, bony erosion, a shift in position, or the need for limited physical activities after initial satisfactory healing has occurred.

4. When completing the intraoral incision and the soft-tissue dissection to expose the surface of the bony chin, avoid subperiosteal dissection above the mental neurovascular bundle to limit the extent of nerve contusion and stretching and the chance of avulsion from the mental foramen. The mucosal incision should be deep in the vestibule to leave a full cuff of mucosa and muscle for ease of two-layer closure and to limit periodontal sequelae.

5. When lengthening the chin, an oblique osteotomy with the interpositional placement of a graft (e.g., allogenic or autogenous bone, porous bloc hydroxyapatite) is generally preferable to the placement of a chin implant (as mentioned in point 3; see Fig. 37-20, G).

6. When vertical reduction and posterior set-back are indicated, the vector of reduction and set-back should generally follow the long axis of the chin prominence. This will avoid step-offs at the junction of the chin osteotomy and the inferior border of the mandible and limit suboptimal aesthetics as a result of the “bunching” of the soft tissues (see Fig. 37-18).

7. When using a reciprocating saw to complete the posterior (lateral) aspect of the oblique chin osteotomy, the inferior border may unknowingly remain partially intact. When this happens, there is a tendency for the uncontrolled fracture of the chin to be more posterior than desired. This can result in an uneven aesthetic result, and it is avoided by carefully completing the lateral and posterior osteotomy before the “splitting” of the chin (see Fig. 37-20, E).

8. When completing a vertical reduction and advancement genioplasty, limit significant step-offs at the junction of the chin osteotomy and the inferior border of the mandible to avoid a palpable ridge or an unattractive “hourglass” appearance to the inferior border of the mandible. A continuous inferior border of the mandible is less likely to accentuate jowling. A significant ridge at the osteotomy site may be prevented by extending the chin osteotomy more posterior (i.e., as far back as first molar); by not “overadvancing” the chin (i.e., in profile, the soft tissue of the chin should not be anterior to the lower lip); and by recontouring any significant step-offs using a rotary drill with a watermelon bur before securing the chin in its new location.

9. When an alloplastic chin implant has failed and requires removal (i.e., as a result of suboptimal aesthetics, infection, bony erosion, or a shift in implant position), chin morphology is generally best restored with a vascularized osseous genioplasty rather than another avascular implant. Unfortunately, the implant will have stretched the overlying soft tissues, resulting in ptosis and possible muscle dysfunction when it is removed. If the chin implant was composed of non-porous material (e.g., Silastic), then a fibrous capsule will have formed, which adds to the residual soft-tissue deformity. Reassessing the overall maxillofacial morphology is essential before proceeding with further chin surgery. A baseline maxillo-mandibular dysharmony may be present and require reconstruction to best achieve patient satisfaction (see Figs. 37-1, 37-7, 37-9, and 37-10).

10. When the surface contour of the chin is severely dysmorphic (i.e., overly pointed or bifid), direct bur recontouring using a rotary drill with a watermelon bur is the preferred approach. This does not negate the simultaneous completion of an oblique osteotomy for the three-dimensional repositioning of the remaining chin unit. Adequate circulation to the distal chin is maintained through the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscle attachments to the genial tubercle.

11. When completing an oblique osteotomy of the chin, the temporary placement of a screw in the distal chin (i.e., one that is only halfway screwed in) that is then clamped with a wire twister (i.e., to be use used as a handle or retractor) is helpful for ease of positioning of the chin before osteotomy fixation (see Fig. 37-20, C and F).

12. Marking the midline of the bony chin with a small vertical notch perpendicular to the proposed horizontal osteotomy helps with the maintenance of chin symmetry before the placement of plate and screw fixation (see Fig. 37-20, C).

13. Adequate fixation of the distal chin across the osteotomy site is reliably carried out with a limited volume of small titanium plates and screws. The type and extent of screws and plates used will vary in accordance with patient-specific fixation needs and surgeon preferences (see Fig. 37-20, F and G).

Complications and Unfavorable Results

Although the majority of patients who have undergone an osseous genioplasty state that they would do it again, complications and suboptimal results will always occur in a minority of cases.*

Injury to the Teeth

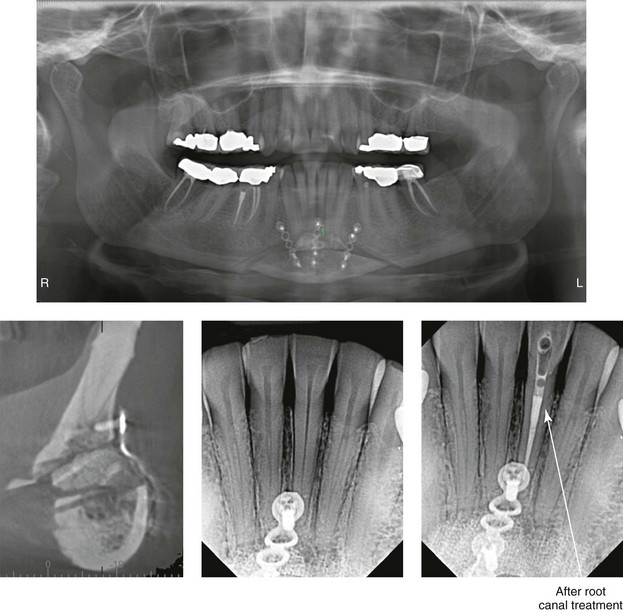

The location of the chin osteotomy should be based on the patient’s chin morphology. The review of the patient’s radiographs (e.g., lateral cephalometric, Panorex) will confirm the anatomy of the anterior teeth and the location of the mental foramen. Injury to the teeth at the time of osteotomy is not common, but it can occur. Dental injury may also occur as a result of the placement of the fixation screws, but this is also not common. If dental injury is suspected, evaluation by the patient’s dentist or referral to an endodontist is recommended. Discussions among the surgeon, the dentist, and the patient are essential, because root canal therapy or other forms of treatment may be indicated (Fig. 37-21).

Figure 37-21 An oblique osteotomy of the chin was carried out (vertical lengthening and horizontal advancement) with interpositional hydroxyapatite grafting. Postoperative radiographs indicate the closeness of the screw fixation to the lateral incisor (1.7-mm diameter and a 4-mm length). Darkening of the crown indicates pulpal injury. Root canal therapy and internal bleaching of the involved tooth were carried out.

Patient Dissatisfaction

1. Accurate preoperative facial and dental assessment by the surgeon and then discussion with the patient of the following: 1) the surgeon’s findings; 2) the patient’s goals; 3) any patient-specific biologic limitations (e.g., soft tissues, skeletal, dental); 4) any baseline head and neck dysfunction that may be related to the chin (e.g., breathing, lip competence); and 5) the surgeon’s overall recommendations

2. A clear understanding among all parties of the operative objectives and any compromises in treatment that have been jointly agreed upon

3. The meticulous execution of the procedures by the surgeon with the patient under controlled anesthesia and with proper instrumentation and assistance

4. At set time intervals after surgery, a discussion with the patient about the results achieved and any shortcomings perceived

Alloplastic Chin Augmentation

Successful chin implants are primarily placed to address mild deficiencies in the sagittal dimension at the pogonion and any limited hypoplasia immediately lateral to the symphysis.128,129 Depending on the philosophy and skill of the surgeon, some vertical lengthening may also be possible.130 Complaints after alloplastic chin augmentation are not infrequent, which may explain their decreased use by board-certified surgeons over a recent 10-year time frame.* Available statistics from the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons confirm an 85% drop in the number of chin implants that were placed between 1997 and 2009 (i.e., 11,000 implants were placed in 1997, whereas 1700 were placed in 2009).101 Although individuals often present with the specific complaint of a “weak chin” and with a seemingly simple request for a “chin implant,” they frequently have a combination of microgenia, mandibular deficiency, and additional associated maxillofacial dysmorphology. A complete systematic soft-tissue and skeletal facial evaluation is required. The surgeon may choose not to discuss associated baseline maxillomandibular skeletal deformities either as a result of a lack of knowledge (i.e., an incomplete diagnosis) or because the patient or family “only requested a chin implant.” In either case, after sagittal chin augmentation, a dissatisfied patient may express bewilderment with the result and at a minimum demand implant removal (see Figs. 37-1, 37-7, 37-9, and 37-10). When indicated, counseling the patient about the preferred orthodontic and orthognathic approach versus camouflage genioplasty alone is advised.

When the facial aesthetic analysis indicates that an implant is an acceptable alternative, a customized porous polyethylene chin augmentation with screw fixation is generally preferred.104,128–130 Silicone (i.e., Silastic) implants heal with a surrounding fibrous capsule. Porous polyethylene implants heal with fibrous tissue in-growth into the open pores. The placement of an appropriately shaped implant with stable fixation will limit the risk of displacement, infection, and erosion of the underlying bone. The obliteration of dead-space gaps (i.e., between the implant and the skeleton) by custom contouring the implant and when applying compressive fixation screws before wound closure is essential. To review, experienced surgeons generally recommend the following: 1) placing a chin implant through a submental incision without intraoral exposure; 2) using an implant of porous material that is customized; and 3) applying stable screw fixation to increase success and limit complications.128–130

Despite the apparent technical ease of placing an alloplastic implant, a disproportionate number of repetitive problems seem to occur after a chin implant.11,24,57,97 A common clinical scenario involves sagittal augmentation with an implant that is excessive in size and that does not address vertical aspects or associated jaw deformity. In these cases, it is generally not just the patient who perceives that the implant is too big; it is hard for the surgeon and other observers at conversational distance to deny the unfavorable aesthetic result, and thus surgeons are forced to honor their patients’ request for implant removal. Unfortunately, depending on the material used, the implant may have caused capsule formation, splaying of the mentalis muscles, and stretching of the overlying soft-tissue envelope. After removal of the “too-large” implant, soft-tissue contracture may occur, which looks even worse with dynamic function (i.e., the soft-tissue “balling up” effect). If mentalis muscle dysfunction remains, there may be unattractive sagging (ptosis) of the soft tissues. Removing the implant and simply placing a smaller one has a low probability of satisfying the patient’s concerns. Facial reassessment may clarify other skeletal deformities (e.g., primary mandibular deficiency, maxillomandibular deficiency, long face growth pattern) that account for the suboptimal result. Many times, after implant removal, a chin osteotomy with three-dimensional repositioning with or without combined orthognathic procedures will give the best result.

References

1. Aufricht, G. Combined nasal plastic and chin plastic: Correction of microgenia by osteocartilaginous transplant from large hump of nose. Am J Surg. 1934; 25:292.

2. Aufricht, G. Combined plastic surgery of the nose and chin. Am J Oral Surg. 1958; 95:231.

3. Becking, AG, Tuinzing, DB, Hage, JJ, Gooren, LJG. Facial corrections in male to female transsexuals: A preliminary report on 16 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 54:413.

4. Bell, WH. Correction of the contour-deficient chin. J Oral Surg. 1969; 27:110.

5. Bell, WH, Brammer, JA, McBride, KL, Finn, RA. Reduction genioplasty: Surgical techniques and soft-tissue changes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981; 51:471.

6. Bell, WH, Dann, JJ, III. Correction of dentofacial deformities by surgery in the anterior part of the jaws. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1973; 64:162.

7. Bell, WH, Gallagher, DM. The versatility of genioplasty using a broad pedicle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983; 41:763.

8. Brennan, HG, Giammanco, PF. The ptotic chin syndrome corrected by mentopexy. Ann Plast Surg. 1987; 18:200.

9. Burstone, CJ. Lip posture and its significance in treatment planning. Am J Orthod. 1967; 53:262.

10. Clark, CL, Baur, DA. Management of mentalis muscle dysfunction after advancement genioplasty: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 62:611.

11. Cohen, SR, Mardach, OL, Kawamoto, HK, Jr. Chin disfigurement following removal of alloplastic chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991; 88:62.

12. Collins, P, Epker, BN. Improvement in the augmentation genioplasty via suprahyoid muscle reposition. J Maxillofac Surg. 1983; 11:116.

13. Connor, AM, Moshiri, F. Advancement genioplasty: An important part of combination surgery in Black American patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988; 93:92–99.

14. Dann, JJ, Epker, BN. Proplast genioplasty: A retrospective study with treatment recommendations. Angle Orthod. 1977; 47:173.

15. Ellis, E, III., Dechow, P, McNamara, J, et al. Advancement genioplasty with and without soft tissue pedicle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984; 42:637.

16. Farkas, LG, Sohm, P, Kolar, JC, et al. Inclinations of the facial profile: Art versus reality. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985; 75:509.

17. Feldman, JJ. The ptotic (witch’s) chin deformity: An excisional approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:207.

18. Field, LM. Correction by a flap of suprahyoid fat of a “witch’s chin” caused by a submental retracting scar. J Dermatol Surg. 1981; 7:719.

19. Finn, RA, Bell, WH, Brammer, JA. Interpositioning grafting with autogenous bone and coralline hydroxyapatite. J Maxillofac Surg. 1980; 8:217.

20. Fitzpatrick, BN. Genioplasty with reference to resorption and the hinge sliding genioplasty. Int J Oral Surg. 1974; 3:247.

21. Flowers, RS. Alloplastic augmentation of the anterior mandible. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:107.

22. Fogel, ML, Stranc, MF. Lip function: A study of normal lip parameters. Br J Plast Surg. 1984; 37:542.

23. Freihofer, HPM. Surgical treatment of the short face syndrome. J Oral Surg. 1981; 39:907.

24. Friedland, JA, Coccaro, PJ, Converse, JM. Retrospective cephalometric analysis of mandibular bone absorption under silicone rubber chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976; 57:144.

25. Gianni, AB, D’Orto, O, Biglioli, F, et al. Neurosensory alterations of the inferior alveolar and mental nerve after genioplasty alone or associated with sagittal osteotomy of the mandibular ramus. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002; 30:295.

26. Gillies, H, Kristensen, HK. Ox cartilage in plastic surgery. Br J Plast Surg. 1951; 4:63.

27. Godin, M, Costa, L, Romo, T, et al. Gore-Tex chin implants: A review of 324 cases. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003; 5:224.

28. Gonzalez-Ulloa, M. Quantitative principles in cosmetic surgery of the face (profile plasty). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1962; 29:186.

29. Gonzales-Ulloa, M. Ptosis of the chin: The witch’s chin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972; 50:54.

30. Gonzales-Ulloa, M, Stevens, E. The role of chin correction in profile plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1961; 36:364–373.

31. Gonzalez-Ulloa, M, Stevens, E. The role of chin correction in profile plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 41:477.

32. Gross, BD, Moss, RA. Cutaneous necrosis of the chin following mandibular advancement and genioplasty. (Case report). J Maxillofac Surg. 1978; 6:140.

33. Guyuron, B, Michelow, BJ, Willis, L. A practical classification of chin deformities. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995; 19:257.

34. Guyuron, B, Kadi, JS. Problems following genioplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1997; 24:507.

35. Guyuron, B, Raszewski, RA. A critical comparison of osteoplastic and alloplastic augmentation genioplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990; 14:199.

36. Hambleton, RS. Tissue covering of the skeletal face as related to orthodontic problems. Am J Orthod. 1964; 50:405.

37. Heidingfield, M. Histopathology of paraffin prosthesis. J Cutan Dis. 1906; 24:513–521.

38. Hinds, EC, Kent, JN. Genioplastic: The versatility of the horizontal osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1969; 27:690.

39. Hofer, O. Die operative behandlung der alveolare retraktion des unterkiefers und ihre anwendungsmoglichkeit fur prognathie und mikrogenie. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferheilkd. 1942; 9:130.

40. Hofer, O. Die osteoplastiche verlagerung des unterkiefers nach von Eiselberg bei mikrogenie. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferheilkd. 1957; 27:81.

41. Hoffman, S. Loss of a Silastic chin implant following a dental infection. Ann Plast Surg. 1981; 7:484.

42. Hohl, TH, Epker, BN. Macrogenia: A study of treatment results, with surgical recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1976; 41:545.

43. Holdaway, RA. A soft tissue cephalometric analysis and its use in orthodontic treatment planning: Part I. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1983; 84:1.

44. Holdaway, RA. A soft-tissue cephalometric analysis and its use in orthodontic treatment planning. Part II. Am J Orthod. 1984; 85:279–293.

45. Holmes, RE, Wardrop, RW, Wolford, LM. Hydroxyapatite as a bone graft substitute in orthognathic surgery: Histologic and histometric findings. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 46:661.

46. Jobe, R, Iverson, R, Vistnes, L. Bone deformation beneath alloplastic implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972; 51:169.

47. Joseph, J. Verbesserung meiner hangewangenplastik (melomioplastik). Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1928; 54:567.

48. Kawamoto, HK. Reduction mentoplasty [discussion]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982; 70:151.

49. Kim, SG, Lee, JG, Lee, YC, et al. Unusual complication after genioplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002; 109:2612.

50. Klawitter, JJ, Bagwell, JG, Weinstein, AM, Sauer, BW. An evaluation of bone ingrowth into porous high density polyethylene. J Biomed Mater Res. 1976; 10:311.

51. Krekmanov, L, Kahnberg, KE. Soft tissue response to genioplasty procedures. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992; 30:87.

52. Legan, HL, Burstone, CJ. Soft tissue cephalometric analysis for orthognathic surgery. J Oral Surg. 1980; 38:744.

53. Lesavoy, MA, Creasman, C, Schwartz, RJ. A technique for correcting witch’s chin deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 97:842.

54. Lindquist, CC, Obeid, G. Complications of genioplasty done alone or in combination with sagittal split-ramus osteotomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1988; 66:13.

55. Loeb, R. Surgical elimination of the retracted submental fold during double chin surgery. J Aesthetic Surg. 1978; 2:31.

56. Matarasso, A, Elias, AC, Elias, RL. Labial incompetence: A marker for progressive bone resorption in Silastic chin augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 98:1007.

57. Matarasso, A, Elias, AC, Elias, RL. Labial incompetence: A marker for progressive bone resorption in Silastic chin augmentation: An update. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 112:676.

58. McBride, KL, Bell, WH. Chin surgery. In: Bell WH, Proffit WR, White R, eds. Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980:1210.

59. McCarthy, JG. Microgenia: A logical surgical approach. Clin Plast Surg. 1981; 8:269.

60. McCarthy, JG, Kawamoto, HK, Grayson, BH, et al. Surgery of the jaws. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990:1332–1333.

61. McCarthy, JG, Ruff, GL. The chin. Clin Plast Surg. 1988; 15:125.

62. McCarthy, JG, Ruff, GL, Zide, BM. A surgical system for the correction of bony chin deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:139.

63. McDonnell, JP, McNeill, RW, West, RA. Advancement genioplasty, a retrospective cephalometric analysis of osseous and soft tissue changes. J Oral Surg. 1977; 35:640.

64. McKinney, P, Rosen, PB. Reduction mentoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982; 70:147.

65. Mercuri, LG, Laskin, DM. Avascular necrosis after anterior horizontal augmentation genioplasty. J Oral Surg. 1977; 35:296.

66. Michelow, BJ, Guyuron, B. The chin: Skeletal and soft-tissue components. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 95:473.

67. Millard, DR. Chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1954; 13:70.

68. Millard, DR. Adjuncts in augmentation mentoplasty and corrective rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965; 36:48.

69. Millard, DR, Pigott, R, Hedo, A. Submental lipectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 41:513.

70. Mole, B. The use of Gore-Tex implants in aesthetic surgery of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:200–206.

71. Mommaerts, MY, Van Hemelen, G, Sanders, K, et al. High labial incisions for genioplasty. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997; 35:398–400.

72. Newman, J, Dolsky, RL, Mai, ST. Submental liposuction extraction with hard chin augmentation. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984; 11:454.

73. Nishioka, GJ, Mason, M, Van Sickles, JE. Neurosensory disturbance associated with the anterior mandibular horizontal osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 46:107.

74. Obwegeser, H. The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty. J Oral Surg. 1957; 10:677–689.

75. Omnell, ML, Tong, DC, Thomas, T. Periodontal complications following orthognathic surgery and genioplasty in 19-year-old: A case report. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1994; 9:133.

76. Ousterhout, DK. Sliding genioplasty, avoiding mental nerve injuries. J Craniofac Surg. 1996; 4:297.

77. Peterson, RA. Correction of the senile chin deformity in face lift. Clin Plast Surg. 1992; 19:433.

78. Polido, WD, de Clairfont, RL, Bell, WH. Bone resorption, stability, and soft-tissue changes following large chin advancements. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991; 49:251.

79. Posnick, JC, Aesthetic alteration of the chin: Evaluation and surgery. Craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery in children and young adults. Posnick, JC, eds. Craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery in children and young adults; vol 43. WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia, 2000:1113–1124.

80. Posnick, JC, Al-Qattan, MM, Stepner, NM. Alteration in facial sensibility in adolescents following sagittal split and chin osteotomies of the mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 97:920.

81. Putnam, JM, Donovan, MG. Modified reduction genioplasty. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989; 47:203.

82. Richard, O, Ferrara, JJ, Cheynet, F, et al. Complications of genioplasty. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 2001; 102:34.

83. Ricketts, RM. Esthetics, environment, and the law of lip relation. Am J Orthod. 1968; 54:272.

Riolo, ML, Moyers, RE, McNamara, JA, Hunter, WS. An Atlas of Craniofacial Growth. In: Monograph No. 2, Craniofacial Growth Series. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan; 1974.

84. Rish, BB. Profile-plasty. Report on plastic chin implants. Laryngoscope. 1964; 74:144.

85. Ritter, EF, Moelleken, BRW, Mathes, SJ, Ousterhout, DK. The course of the inferior alveolar neurovascular canal in relation to sliding genioplasty. J Craniofac Surg. 1992; 3:20.

86. Robinson, M. Bone resorption under plastic chin implants: Follow-up of a preliminary report. Arch Otolaryngol. 1972; 95:301.

87. Robinson, M, Schuken, R. Bone resorption under plastic chin implants. J Oral Surg. 1969; 27:116.

88. Rosen, HM. Surgical correction of the vertically deficient chin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988; 82:247.

89. Rosen, HM. Porous, block hydroxyapatite as an interpositional bone graft substitute in orthognathic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 83:985.

90. Rosen, HM. Aesthetic refinements in genioplasty: The role of the labiomental fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991; 88:760.

91. Rosen, HM. Aesthetics in facial skeletal surgery. Perspect Plast Surg. 1992; 6:1.

92. Rosen, HM. Facial skeletal expansion: Treatment strategies and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 89:798.

93. Rosen, HM. Aesthetic guidelines in genioplasty: The role of facial disproportion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 95:463.

94. Rosen, HM. Autogenous chin augmentation. J Plast Surg Tech. 1997; 115:22.

95. Safian, J. Progress in nasal and chin augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966; 37:446.

96. Satoh, K, Tsukagoshi, T, Shimizu, Y. Surgical refinement of the operative procedure for a minor degree of mandibular prognathism. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 98:740.

97. Sclaroff, A, Williams, C. Augmentation genioplasty: When bone is not enough. Am J Otolaryngol. 1992; 13:105.

98. Shaughnessy, S, Mobarak, KA, Høgevold, HE, Espeland, L. Long-term skeletal and soft-tissue responses after advancement genioplasty. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 130:8–17.

99. Simons, RL, Lawson, W. Chin reduction in profile plasty. Arch Otolaryngol. 1975; 101:207.

100. Smith, HW. Surgical correction of chin ptosis. Am J Cosmetic Surg. 1985; 2:6–15.

101. Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery: 2009 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank American Statistics. New York.

102. Spear, SL, Kassan, M. Genioplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1989; 16:695.

103. Spear, SL, Mausner, M, Kawamoto, HK. Sliding genioplasty as a local anesthetic outpatient procedure: A prospective two-center trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987; 80:55.

104. Spector, M, Flemming, WR, Sauer, BW. Early tissue infiltrate in porous polyethylene implants into bone: A scanning electron microscope study. J Biomed Mater Res. 1975; 9:537.

105. Steiner, CC. Cephalometrics in clinical practice. Angio Orthod. 1959; 29:8.

106. Storum, KA, Bell, WH, Nagura, J. Microangiographic and histologic evaluation of revascularization and healing after genioplasty by osteotomy of the inferior border of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 48:210–216.

107. Terino, EO. Complications of chin and malar augmentation. In: Peck G, ed. Complications and problems in aesthetic plastic surgery. New York: Gower Medical, 1991.

108. Terino, EO. Alloplastic facial contouring by zonal principles of skeletal anatomy. Clin Plast Surg. 1992; 19:487.

109. Terino EO: Versatile “chin implant” to alter the lower 1/3 facial segment. Presented at the Symposium, Advances in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery: The Cutting Edge II. New York, NY, November 12, 1998.

110. Trauner, R, Obwegeser, H. The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty: I. Surgical procedures to correct mandibular prognathism and reshaping of the chin. Oral Surg. 1957; 10:677.

111. Trauner, R, Obwegeser, H. The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty. II. Operating methods for microgenia and distoocclusion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1957; 10:787–792.

112. Tweed, C. Frankfort-mandibular incisor angle (FMIA) in orthodontic treatment planning and prognosis. Angle Orthod. 1954; 24:121.

113. Van Sickels, JE, Hatch, JP, Dolce, C, et al. Effect of age, amount of advancement and genioplasty on neurosensory disturbance after a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002; 60:1012.

114. Vedtofte, P, Nattestad, A, Hjirting-Hansen, E, et al. Bone resorption after advancement genioplasty: Pedicled and non-pedicled grafts. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991; 19:102.

115. Wellisz, T, Kanel, G, Anooshian, RV. Characteristics of the tissues response to Medpor porous polyethylene implants in the human facial skeleton. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 1993; 3:223.

116. Wessberg, GA, Wolford, LM, Epker, BN. Interpositional genioplasty for the short face syndrome. J Oral Surg. 1980; 38:584.

117. Westermark, A, Bystedt, H, Von Konow, L. Inferior alveolar nerve function after mandibular osteotomies. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998; 36:425.

118. Wider, TM, Spiro, SA, Wolfe, SA. Simultaneous osseous genioplasty and meloplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99:1273.

119. Wilcox, JW, Hickory, JE. Percutaneous total genioplasty. J Oral Surg. 1978; 36:706.

120. Wolfe, SA. Chin advancement as an aid in correction of deformities of the mental and submental regions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981; 67:624.

121. Wolfe, SA. (Discussion of) Chin surgery: I. Augmentation—The allures and the alerts, and Chin Surgery: II. Submental ostectomy and soft-tissue excision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 104:1861.

122. Wolfe, SA. (Discussion of) Sliding genioplasty as a local anesthetic outpatient procedure: A prospective two-center trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987; 80:67.

123. Wolfe, SA. Shortening and lengthening the chin. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1987; 15:223.

124. Wolfe, SA. The genioplasty: An essential tool in the correction of chin deformities. In: Ousterhout DK, ed. Aesthetic contouring of the craniofacial skeleton. Boston: Little, Brown; 1991:409–430.

125. Wolfe, SA, Berkowitz, S. The chin. In: Wolfe SA, Berkowitz S, eds. Plastic surgery of the facial skeleton. Boston: Little, Brown; 1989:111–148.

126. Wolfe, SA, Posnick, JC, Yaremchuk, MJ, Zide, BM. Panel discussion: Chin augmentation. Aesthet Surg J. 2004; 24(3):247–256.

127. Wolford, LM. Porous, block hydroxyapatite as an interpositional bone graft substitute in orthognathic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 83:6.

128. Yaremchuk, MJ. Mandibular augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:697.

129. Yaremchuk, MJ. Facial skeletal reconstruction using porous polyethylene implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 111:1818.

130. Yaremchuk, MJ. Improving aesthetic outcomes after alloplastic chin augmentation. J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 112:1422–1432.

131. Zeller, SD, Hiatt, WR, Moore, DL, et al. Use of preformed hydroxyapatite blocks for grafting in genioplasty procedures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 15:665.

132. Zide, BM. Chin disfigurement following removal of alloplastic chin implants [discussion]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991; 88:68.

133. Zide, BM. The mentalis muscle: An essential component of chin and lower lip position. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:1213.

134. Zide, BM, Boutros, S. Chin surgery: III. Revelations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 111:1542.

135. Zide, B, Longaker, MT. Chin surgery: II. Submental ostectomy and soft-tissue excision. J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 104:1854–1860.

136. Zide, BM, McCarthy, JG. The mentalis muscle: An essential component of chin and lower lip position. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 83:413.

137. Zide, BM, Pfeifer, TM, Longaker, MT. Chin surgery: I. Augmentation—The allures and the alerts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 104:1843.

*References 5, 12, 15, 19, 35, 38–40, 42, 47, 48, 55, 58, 62, 63, 71, 74, 76, 78, 81, 93, 94, 96, 102, 103, 110, 111, 119, 122, 134

*References 7, 10, 11, 17, 18, 20, 24, 25, 29, 32, 34, 49, 53, 54, 65, 72, 73, 75, 80, 82, 85, 98, 100, 113, 114, 117, 121, 133, 136, 137

*References 8, 11, 14, 21, 24, 26, 27, 37, 41, 46, 50, 56, 57, 67, 68, 70, 72, 84, 86, 87, 97, 107–109, 115, 132