Aesthetic Alteration of Prominent Ears

Evaluation and Surgery

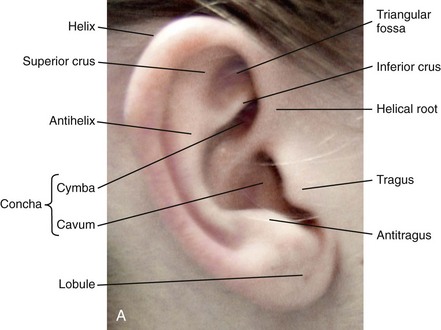

Aside from the excision of auricular tags and the repair of traumatically clefted ear lobes, the prominent ear is the most commonly treated external ear deformity. Approximately 5% of the Caucasian population has protruding ears, thereby making this the most frequent congenital anomaly of the external ear. Otoplasty is a common aesthetic operation that is carried out among children and adolescents to address this issue. There is a wide variation with regard to what is considered normal for ear size, prominence, and shape (Fig. 39-1). An “outstanding” ear is said to be present when the distance of the helical rim from the temporomastoid surface of the skull is excessive. As a general rule, a measurement of more than 16 to 21 mm is said to result in a prominent ear (Fig. 39-2). The average ear is 6.5 cm long and 3.5 cm wide, but significant variations are considered acceptable. After the completion of normal ear growth and with ongoing age, the external ear changes in that the elongation of the soft tissue covering and the earlobe is to be expected. Provided that the ear has a morphology that is in balance with the other facial features and that there is reasonable symmetry from one ear to the other, these variations are considered to be in an acceptable aesthetic range. However, when ear shape, size, and proportion are perceived as distracting to the casual observer at conversational distance, the ears may become a source of ridicule and personal anguish. Affected children are frequently stigmatized by their peers and commonly ask their parents if a solution for their visible abnormal ear shape can be found. In these circumstances, the surgical correction of the prominent ear is likely to have a beneficial effect on the person’s self-esteem and body image.

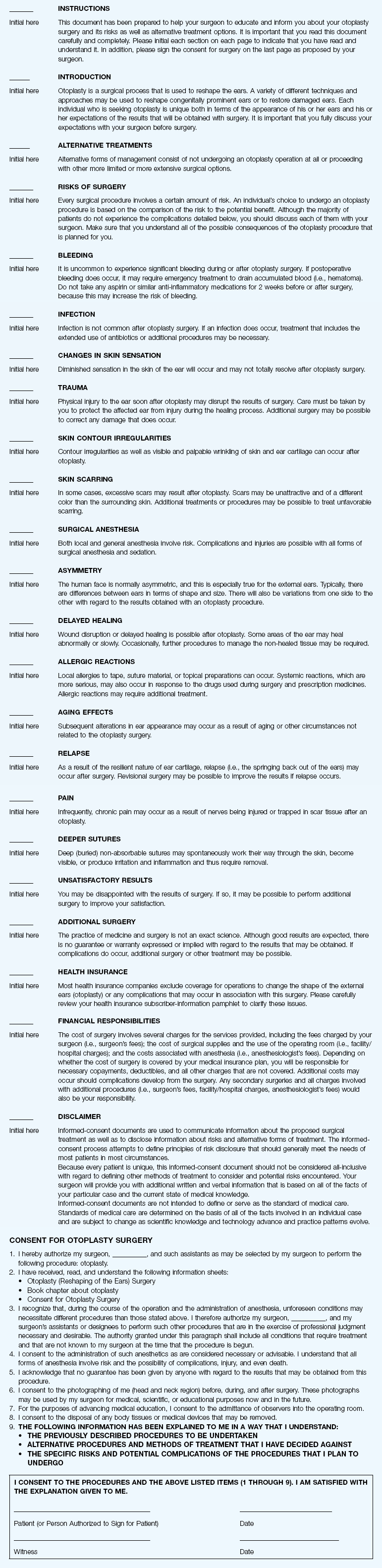

Figure 39-1 A, The topographic anatomy of the external ear is shown. Key anatomic landmarks are demonstrated and labeled. B, Drawing by Leonard da Vinci that confirms the importance of achieving Euclidian proportions of the external ear within the face.

Figure 39-2 Ear protrusion is measured as the distance of the helical rim from the cranium; it is measured in millimeters. The specific locations where measurements are taken include the helical apex, the midpoint, and the lobe.

A failure of scaphal folding (i.e., limited antihelical fold) as well as conchal hypertrophy (i.e., increased depth of the conchal wall), prominent lobules (i.e., protruding ear lobes); and anterolateral rotation of the concha (i.e., cupping of the ear) frequently create prominence of the external ear.5,13,14,30,52,57,67 Noticeable ear protrusion often results from a combination of these deformities. An accurate assessment of the ear dysmorphology is essential to the achievement of an unobtrusive look through surgery. Adjusting the scaphal (antihelical) folding with sutures, reducing the conchal wall depth via conchal excision and conchal mastoid sutures, and performing lobe set-back with sutures and excision are typical components of the surgical correction that is undertaken to achieve a favorable result.3,4,6,11,26,50,55,60,70,72

Overemphasis on the surgical creation of an antihelical fold without paying proper attention to conchal hypertrophy often results in an oversharpened antihelix and a buried helical rim (i.e., “telephone ear”). Some surgeons advocate cartilage-cutting (i.e., scoring) procedures rather than sutures to achieve a preferred antihelical fold.11 These cartilage-scoring techniques generally require dissection of the soft tissues off of the anterior surface of the cartilage. This can result in hematoma, skin necrosis, and chondritis, which may result in irreversible cartilage or external ear irregularities. Surgical correction of the outstanding ear should in general be uncomplicated and result in reliable, long-lasting, favorable aesthetics with minimal downtime for the patient and minimal chance of relapse.

When considering the ideal timing for external ear surgery, it is important to balance what we know about ear and facial growth, psychosocial development, and the ability of the child to comply with the necessary routines after surgery.1,20,21,39 The goals of otoplasty for the management of congenitally prominent ears, as outlined by McDowell, remain universal despite a multitude of etiologies and suggested surgical techniques.42 According to McDowell, the surgical goals should include the following:

1. Correcting ear protrusion, by addressing the over prominent helix and antihelix

2. Achieving a smooth antihelical fold without a “sharp” crease

Historic Perspective

Dieffenbach is credited with reporting the first otoplasty in the medical literature in 1845.15 This was performed to reconstruct a traumatically deformed ear. The ear surgery consisted of excising skin from the postauricular sulcus and suturing the conchal cartilage to the mastoid periosteum (i.e., conchal–mastoid suturing). In 1881, Ely was the first surgeon to report a procedure for the aesthetic correction of a congenitally prominent ear.19 He resected both the skin and the conchal cartilage, but he did so as a two-stage procedure (i.e., one ear at a time).56 Moristin further developed these skin-excision and cartilage-resection otoplasty techniques.44 In 1910, Luckett realized that a prominent ear frequently resulted from the congenital failure to form an antihelical fold.38 He was the first to describe setting the ear back via the removal of postauricular skin and by simultaneously completing an incision through the length of the ear cartilage in an attempt to create the deficient antihelical fold; he also placed sutures to hold the new fold in place. In 1960, Stenstrom used the known principles of cartilage biology as described by Gibson and Davis in 1958 to propose the scoring and abrading the anterior cartilage surface to weaken it and thereby create an antihelical fold.61,62,25 In 1963, Mustarde introduced the placement of mattress sutures in the posterior cartilage surface of the ear as a technique for the creation of a new antihelical fold.46–48

In 1967, Kaye combined the anterior scoring technique of Stenstrom and the posterior suture placement technique of Mustarde to limit the relapse that surgeons complained about when using either technique alone; he also advocated the use of nonresorbable suture.32 In 1968, Furnas reintroduced the technique of conchal–mastoid suturing to set back the prominent conchal bowl.22–24 He also advocated cleaning out the soft tissue in the postauricular groove (i.e., postauricular muscle and fibrofatty tissue) so that the concha could be rotated in a sagittal plane from posterior to anterior (clockwise rotation) before anchoring it to the mastoid fascia (conchal–mastoid sutures) with nonresorbable sutures. In 1969, Webster advocated paying special attention to the prominent earlobe to achieve a successful otoplasty.69 He noted that the “tail” of the helix could be repositioned with suture to change the lobe’s orientation. In 1972, Elliott combined and refined all of the previously described techniques to manage, the deep conchal wall, the limited antihelical fold, and the abnormal earlobe that were frequently seen in the prominent ear.18 He advocated the use of elliptical partial conchal wall excision when conchal–mastoid suturing alone was felt to be insufficient to correct the ear prominence. He used an anterior incision placed within the “shadow zone” of the conchal margin when conchal resection was required. Bauer advocated the use of the Elliott anterior conchal cartilage excision but preferred to also excise anterior skin to avoid postoperative skin folding or bunching.4

Embryology and Anatomy

Embryologically, the ear arises from six hillocks of the first and second branchial arches during the second to fourth month of gestation. Hillocks 1 through 3, from the first arch, form the anteromedial aspects of the auricle (i.e., the tragus, the helical crus, and the helix, respectively). Hillocks 4 through 6, from the second arch, develop into the posterolateral aspects of the ear (i.e., the antihelix and the antitragus, respectively).34,35 During the third month of gestation, protrusion of the auricle increases. By the end of the sixth month, the helical margin curves, the antihelix forms its folds, and the antihelical crura appear at the superior aspect of the forming external ear. Congenital ear deformities result from the disruption of one or more of the auricular hillocks during embryogenesis. Any deforming forces to the side of the head of the fetus may also alter the shape of the external ear.

The ear is supplied by branches from the superficial temporal artery anteriorly and the posterior auricular and occipital arteries posteriorly. The superficial temporal, posterior auricular, and retromandibular veins provide venous drainage. The lymphatic drainage of the anterior three hillocks is mainly to the anterior triangle of the neck, whereas the posterior three hillocks ultimately drain into the posterior triangle of the neck. Lastly, the ear is supplied by the great auricular nerve on its lower lateral and inferior cranial surfaces, by the lesser occipital nerve on its superior cranial surface, and by the auriculotemporal nerve on its superior lateral surface as well as the anterior superior surface of the external acoustic meatus. The Arnold nerve, which is an auricular branch of the vagus nerve, supplies the posterior inferior external auditory canal and meatus as well as the inferior conchal bowl.34,35

Bauer pointed out that the external ear may be thought of as consisting of a three-tiered cartilaginous framework with tightly adherent skin on the anterior surface and loosely applied skin on the posterior surface.4 The three tiers of sculpted cartilage form are the helical–lobular complex, the antihelical–antitragal complex, and the conchal complex. Key anatomic (aesthetic) landmarks of the normal ear include the scapha, the concha, the helix, the antihelix, the tragus, and the lobule (see Figs. 39-1 and 39-2).

Timing of Surgery

In a study by Farkas, two anthropometric surface measurements, ear width and ear length, were taken directly from the ears of normal subjects with the use of an anthropometric sliding caliper.20,21 At the age of 1 year, ear width is highly developed in both sexes (mean, 93.5%), and it is mostly completed at the age of 5 years (mean, 97%). The width of the ear reaches its full mature size in boys at the age of 7 years and in girls at the age of 6 years. At 1 year of age, the length of the ear has already attained 75% of its eventual adult size. By 5 years of age, 87% of its eventual development is observed. Ear length achieves its full adult size in 13-year-old boys and 12-year-old girls. Adamson and colleagues reviewed the growth patterns of the external ear and concluded that the ear reaches 85% of its overall adult size by the age of 3 years and that little change in ear width or the distance of the ear from the scalp occurs after 10 years of age.1 The authors concluded that, for all practical purposes, the normal ear is almost fully developed by the age of 6 years.

Although children notice differences in each other beginning very early in life, they are rarely self-conscious about differences in ear protrusion before 5 years of age.39 From this point on, however, social interactions with peers frequently elicit negative comments that can affect self-esteem and body image. The correction of external ear deformities before this age is possible, but the postoperative course may be compromised if the ear bandage is removed early by the uncooperative child or with disruption of the repair by pulling on the ears after the bandage is removed. Consideration is given to setting back the protruding ears as early as 3 years of age, although many children display improved cooperation and parents are more confident in their decision when children are between the ages of 5 and 6 years.

Aesthetic Objectives

It is recognized that there are wide variations with regard to ear proportions, projection, and position among individuals. When feasible, the surgically reconstructed (previously protruding) ear should be of ideal size and shape and have a good relationship with the other facial features and the contralateral ear. Loose guidelines for the assessment of preferred ear shape and position have been summarized by Tolleth.67

Surgical Principles

Historically, the creation of an antihelical fold was carried out by techniques that involved either scoring or abrasion of the cartilage to control the direction and extent of folding.16,25,28 Later, suture techniques (i.e., Mustarde sutures) were added to reshape the cartilage. Many surgeons combine these methods. Interestingly, some “cartilage scorers” recommend partial-thickness scoring, whereas others score the full thickness of the cartilage.11 This author prefers to avoid scoring the cartilaginous surface all together, because this requires separation of the anterior skin from the cartilage surface with increased risk of hematoma, flap necrosis, and visible sharp edges on the anterior (cartilage) surfaces. The careful placement of Mustarde mattress sutures in a gentle curve will form a smooth antihelical fold. The Mustarde sutures are placed along the posterior surface of the cartilage as needed in the upper, middle, and lower thirds to accomplish aesthetic antihelical folding.46–48

Conchal hypertrophy is a frequent component of the ear deformity. The correction of this aspect is usually accomplished through a combination of techniques, including the following: 1) the repositioning of the concha into the surgically “cleaned out” mastoid recess; 2) conchal set-back with conchal–mastoid sutures; and 3) conchal reduction through direct elliptical cartilage excision. If the anterior approach is selected for conchal wall resection, an incision (scar) must be placed on the anterior surface, but the folding of redundant skin is limited.4 If a posterior approach is used, there is a risk that the redundant anterior skin that is left behind may not shrink sufficiently and thus result in a visible fold in the conchal floor. Some surgeons believe that a redundant anterior skin fold may be more noticeable than a “fine” anterior conchal scar. This author prefers to excise conchal cartilage with the use of a posterior approach. The anterior skin is then released from the residual conchal floor cartilage to avoid bunching, as discussed later in this chapter.

Surgical Technique (Figs. 39-3 through 39-9)

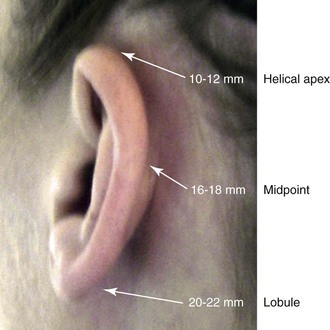

Figure 39-3 Intraoperative views of postauricular skin incisions and excision as part of otoplasty. A, The location of the postauricular elliptical skin excision is demonstrated. The planned long axis of the ear excision extends from the superior helical rim to the earlobe. B, With the use of a knife (No. 15 blade), the full thickness of the skin ellipse is incised. C, With the use of blunt-tip Stevens scissors, the full thickness of the skin ellipse is removed, down to the surface of the cartilage.

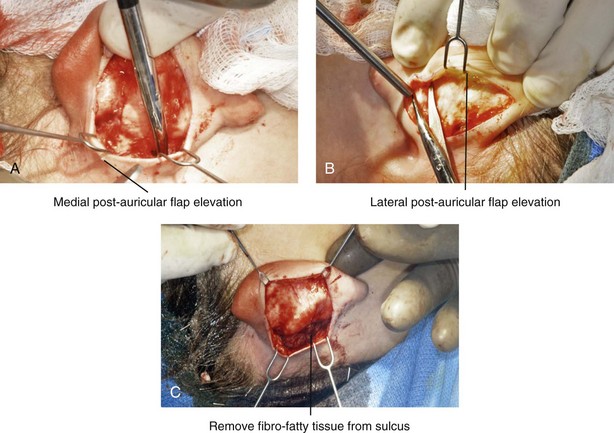

Figure 39-4 Intraoperative views of postauricular flap elevation and then subcutaneous tissue excision as part of otoplasty. A, Elevation of the medial postauricular flap is completed down to the mastoid fascia. B, Elevation of the lateral postauricular flap is extended to the outer edge of the helical rim. The flaps are also elevated inferiorly to the tail of the helix and superiorly to the upper aspect of helix. C, All soft tissue is cleaned out in the sulcus down to mastoid fascia (i.e., muscle and fibrofatty tissue).

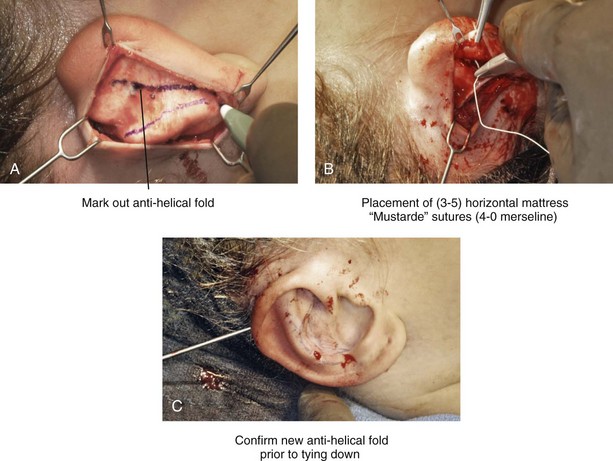

Figure 39-5 Intraoperative views of the creation or deepening of the preferred antihelical fold as part of the otoplasty. A, The preferred antihelical fold is located and marked on the posterior surface of cartilage with a surgical pen or methylene blue. B, The new antihelical fold is created or deepened by placing three to five carefully located horizontal mattress (Mustarde-type) sutures. The sutures are placed in a natural curve like the spokes of a wheel. Each placed Mustarde suture is tested for effectiveness with a single throw, after which it is loosened. C, After all sutures have been placed and tested, each will be carefully tied and confirmed for the preferred aesthetic effect. Note that the conchal wall excision is completed prior to placement of Mustarde stitches. Only after all of the Mustarde stitches have been secured, are the edges of the conchal walls (after elliptical excision) approximated with the use of interrupted sutures.

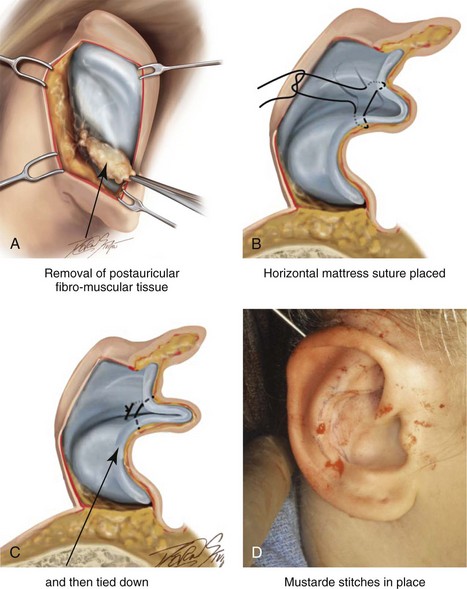

Figure 39-6 Illustrations and patient example of the surgical correction of an antihelical fold. A, Illustration that demonstrates the removal of redundant fibromuscular tissue from the postauricular fold. B, Illustration that demonstrates the placement of a Mustarde stitch before tie down (cross section view). C, Illustration of a tied-down Mustarde stitch (cross section view). D, Intraoperative view of the anterior surface of the ear just after the placement of five Mustarde stitches that were used to create the preferred antihelical fold.

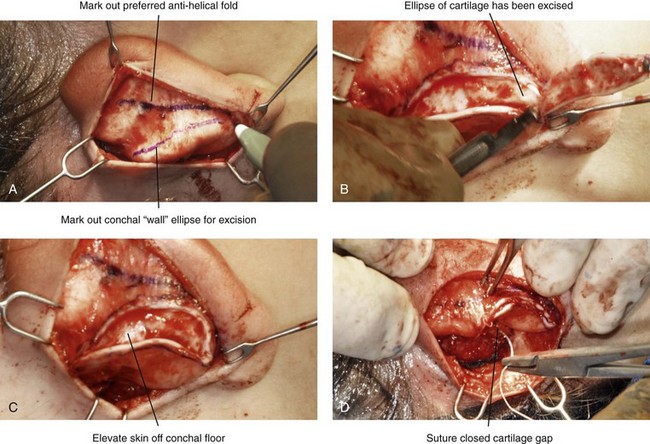

Figure 39-7 Intraoperative views of conchal wall resection and reconstruction as part of otoplasty. A, The preferred antihelical fold is located on the posterior surface of the cartilage and marked with a surgical pen or methylene blue. In addition, the long axis for the planned elliptical excision of the conchal wall is located and marked on the posterior surface of the cartilage. B, The full thickness of the conchal wall ellipse for excision is incised through the cartilage with a knife (No. 15 blade) but without perforation through the anterior skin. The cartilage is then removed with the use of a Cottle elevator and Stevens scissors. This image was created after the ellipse of cartilage had been excised. C, Next, the anterior ear skin is elevated off of the residual conchal floor toward the ear canal. This is accomplished to limit bunching of the skin during the healing phase after the conchal wall edges are reapproximated with suture. D, The edges of the cut conchal wall are sutured together to limit overlap during healing. Note that it is best to suture the conchal edges together only after the Mustarde sutures are placed and tied.

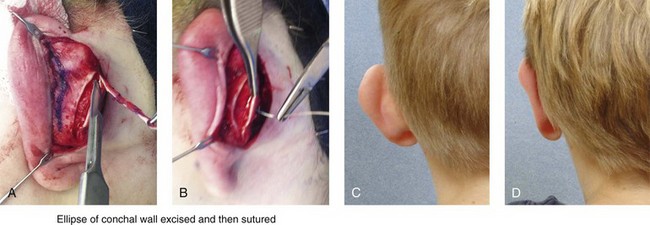

Figure 39-8 Illustration and patient example of deep conchal bowl correction. A, Illustration of the postauricular approach for access and then for the excision of the ellipse of the conchal wall. B, Intraoperative view after the elliptical excision of the conchal wall to “set-back” the ear. The anterior soft tissues of the ear remain intact. C and D, Clinical example of a child with a deep conchal bowl before and after surgical correction.

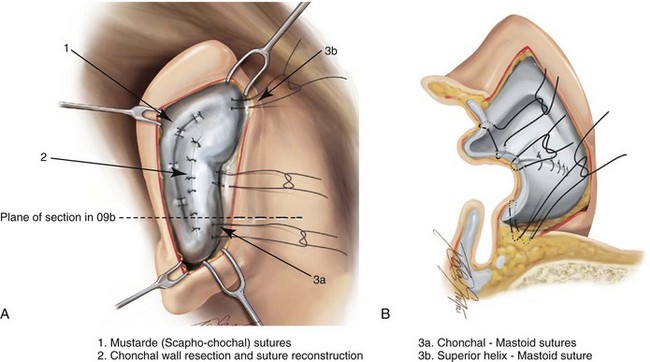

Figure 39-9 Illustrations of a postauricular approach to the management of a prominent ear. Frequently, three rows of sutures are required for successful ear set-back. A, The illustration demonstrates the three rows of sutures being placed, but they are not yet tied down (cross section view). B, Illustration of the three rows of sutures (post auricular view) after they are tied down. The three rows of sutures include the following: 1) Mustarde (scaphoconchal) sutures; 2) conchal wall resection and then suture reconstruction of the cartilage defect; and 3) conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures.

The postauricular incisions (i.e., elliptical skin excision) are completed with a scalpel (see Fig. 39-3). All soft tissue down to the posterior surface of the cartilage is removed. The postauricular medial and lateral skin flaps are elevated (see Fig. 39-4). The resection and removal of postauricular muscle and fibrofatty tissue that is between the conchal cartilage and the mastoid fascia is completed. This allows the concha to rest in a deep pocket so that the bending of the cartilage over a soft-tissue mound does not occur when tying conchal–mastoid sutures (Fig. 39-6A).

When scaphal folding is needed to improve the antihelical fold, the placement of postauricular horizontal mattress (Mustarde-type) sutures is carried out (see Figs. 39-5 and 39-6). Before the creation of the improved antihelical fold, the posterior cartilaginous surface is cleaned of all soft tissue. The Mustarde sutures are placed in a radial fashion to form a curved scaphal fold that extends from the superior crus down to the lobule. Antihelical reconstruction usually requires three to five Mustarde sutures to achieve a smooth roll. Each suture is tested for its effectiveness after it is placed, but none are tied until all are in position. If the position of the superior helix remains protruded, one or two additional superior helix–mastoid sutures can be placed to further accomplish the ear set-back.

A conchal set-back with sutures (conchal–mastoid sutures) is useful but generally inadequate for the management of even moderate degrees of conchal hypertrophy. Partial conchal wall resection is generally indicated (see Figs. 39-7 through 39-9). This author prefers to complete the resection through a posterior approach. An ellipse of the conchal wall that extends superiorly and inferiorly is excised to allow the bowl to reposition itself without a cartilaginous “dog ear” (i.e., puckering). If only minor degrees of conchal prominence exist, management just with the placement of conchal–mastoid sutures may be possible.

Otoplasty for Prominent Ears: Step-by-Step Approach

Preparation and Draping

• If the patient has long hair, tie it in a ponytail; this will keep the hair out of the surgical field.

• Prep the patient’s entire scalp, forehead, external ears, face, and neck.

• Use Betadine solution (do not use soap, alcohol, Hibiclens, and so on) to avoid irritation of the mucous membranes and the corneas of the eyes.

• Drape the patient, leaving the anterior scalp, forehead, external ears, face, and neck exposed in the operative field.

Surgical Markings

• Before preparation, use a surgical pen to locate and mark the preferred location of the antihelical fold on the anterior aspect of the ear, including the superior and inferior crus.

• Before preparation, use a surgical pen to locate and mark the postauricular elliptical skin excision. Center the ellipse at the long axis of the ear from the superior helical rim to the earlobe. Stop the ellipse approximately 1 cm short of the superior and inferior margins of ear.

Elevation of the Postauricular Flaps (see Fig. 39-4)

• Elevate the lateral postauricular skin flap near the outer edge of the helical rim.

• Elevate the medial postauricular skin flap down to the mastoid fascia.

• Clean out all soft tissue (i.e., muscle and fibrofatty tissue) in the sulcus down to the mastoid fascia.

• Confirm the adequate elevation of the flaps inferiorly (to the tail of the helix) for later control of the earlobe position and superiorly (the upper aspect of the helix) for later control of the position of the upper third of the helix.

Marking of the New Antihelical Fold on the Posterior Surface of the Cartilage

• With the use of a 27-gauge needle (i.e., a tuberculin syringe filled with methylene blue), puncture through the anterior surface of the skin along the previously marked location of the new antihelical fold.

• Visualize the needle on the posterior surface of the cartilage, and use a surgical pen or methylene blue to mark the location of the new fold along the full length from the superior crus to the tail. This will allow for the accurate placement of the Mustarde-type sutures.

• Mustarde sutures are not placed until after conchal wall resection is complete.

Conchal Wall Resection for Set-Back (see Figs. 39-7 and 39-8)

• The planned elliptical excision of the conchal wall (superior to inferior) is marked out with a surgical pen or methylene blue on the posterior surface of the cartilage.

• The conchal excision should include a portion of the conchal wall. The full thickness of the ellipse of concha for excision is incised with a scalpel (no. 15 blade) but without perforation through the anterior skin.

• With the use of a Cottle elevator, the incised ellipse of cartilage is freed from the anterior ear skin and then removed.

• The anterior ear skin is further elevated off of the residual concha floor toward the ear canal. This will limit bunching of the skin during the healing phase after the conchal wall edges are reapproximated with suture.

• The edges of the cut conchal wall will be sutured together with 4-0 Vicryl to limit overlap. Wait to suture the edges together until the Mustarde sutures are placed and tied.

Deepening or Creation of the Antihelical Fold (see Figs. 39-5 and 39-6)

• The new antihelical fold is created or deepened by placing three to five carefully located horizontal mattress (Mustarde-type) sutures. The sutures are placed in a natural curve like the spokes of a wheel.

• Experience has taught that cartilage scoring is not necessary and can cause complications (e.g., hematoma, skin flap necrosis, sharp edges).

• Each placed Mustarde suture is tested for effectiveness with a single throw, after which it is loosed.

• When all sutures have been placed and tested, each is carefully tied and confirmed for the preferred aesthetic effect.

• Experience has taught that use of non-resorbable suture (4-0 Mersilene or 4-0 clear nylon) is useful to limit or prevent late cartilage relapse with the loss of the antihelical fold.

Placement of Conchal–Mastoid Sutures to Further the Set-Back of the Middle Third of the Ear (see Fig. 39-9)

• Conchal–mastoid sutures are placed as needed only after the conchal wall is resected and reconstructed with sutures and the Mustarde sutures have been placed. The conchal–mastoid sutures should be made of a non-resorbable material (4-0 Mersilene or 4-0 clear nylon) to limit cartilage relapse. They are placed to establish the preferred clockwise rotation of the ear and to further set back the middle concha, as needed.

• If more than one conchal–mastoid suture is required, each is placed and tested with a single throw and then loosened.

• When all of the conchal–mastoid sutures have been placed and tested, each one is tied to confirm the preferred aesthetic effect.

Placement of Superior Helix–Mastoid Sutures to Further the Set-Back of the Upper Third of the Ear

• The superior helical rim may remain “outstanding” more than is preferred even after the placement of Mustarde sutures. A superior helical–mastoid suture (4-0 Mersilene or 4-0 clear nylon) is often useful to further improve the aesthetic result. The combination of these surgical maneuvers will limit a sharp edge in the antihelical fold that may otherwise occur as a result of the overtightening of the Mustarde sutures.

Set-Back of the Earlobe (Lower Third of Ear)

• Excision of the postauricular skin and the subcutaneous tissue of the lobe is sometimes helpful to set back the lower third of the ear.

• The placement of a tail of helix–mastoid or tail of helix–conchal base suture with the use of non-resorbable material (4-0 Mersilene or 4-0 clear nylon) is sometimes helpful to control the lobe position.

Placement of Dressing (Fig. 39-10)

Figure 39-10 A 5-year-old with prominent ears underwent reconstruction. He is shown before and 5 days after reconstruction at the time of bandage removal. After bandage removal, the patient was allowed to wash the hair, face, and ears in the shower with soap and water. Other than avoiding direct trauma or forward folding of the ears while sleeping, the ears are then left open to the air.

• A thick coat of antibiotic ointment is placed in the postauricular fold and over the anterior ear skin surface.

• A sheet of gauze (Xeroform) is placed in the postauricular groove and also along the anterior ear surface.

• Two or three pieces of dry fluff gauze are placed over the anterior skin surface of each ear.

• A gauze roll (Kerlix) is used as a wrap to apply gentle pressure and to hold the gauze fluffs in place. The Kerlix wrap is also secured across the anterior neck to prevent the head dressing from loosening.

• An Ace wrap is then loosely placed as an outer layer of the head and ear dressing.

Postoperative Care

• After the ear dressing is removed, the patient is encouraged to shower and shampoo the hair and to wash the external ears, face, and neck one or two times daily. (Overly hot water should be avoided, because the ears will have diminished sensation.)

• The ears are dabbed dry after washing. (Excess rubbing of the ears should be avoided.)

• Ear protection is used when sleeping for 2 to 3 months to prevent accidental anterior folding of the external ears. A skier’s ear warmer or a tennis sweatband may be used for this purpose.

• No vigorous sports activities are allowed for 4 to 6 weeks.

• No strong sun (ultraviolet) exposure to the ears is allowed for approximately 3 months.

• When the patient has returned to more regular physical or sports activities after 4 to 6 weeks, additional precautions are encouraged, depending on type of sport activity (e.g., wrestling, basketball), during the initial 3 months after surgery.

Assessment of Results

Although prominent ears do not have any physiologic disadvantages, they play an important role in social life. Prominent ears often provoke teasing by others, especially by children; they can lead to emotional stress with a decline in the patient’s health-related quality of life; they may negatively affect school or job performance; and they may result in social avoidance and a loss of self-confidence (Figs. 39-11 through Fig. 39-27). Today, health-related quality of life is considered by many to be the most important parameter for the evaluation of aesthetic procedures such as the correction of protruding ears.7,64

Figure 39-11 A 4-year-old girl with asymmetric prominent ears that are characterized by conchal hypertrophy and deficient scaphal folding. She underwent elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures); and the creation of improved antihelical folds (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Posterior facial views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-12 A 7-year-old girl with asymmetric prominent ears that are characterized by both conchal hypertrophy and deficient scaphal folding. She underwent elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures); and the improvement of the antihelical folds (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction.

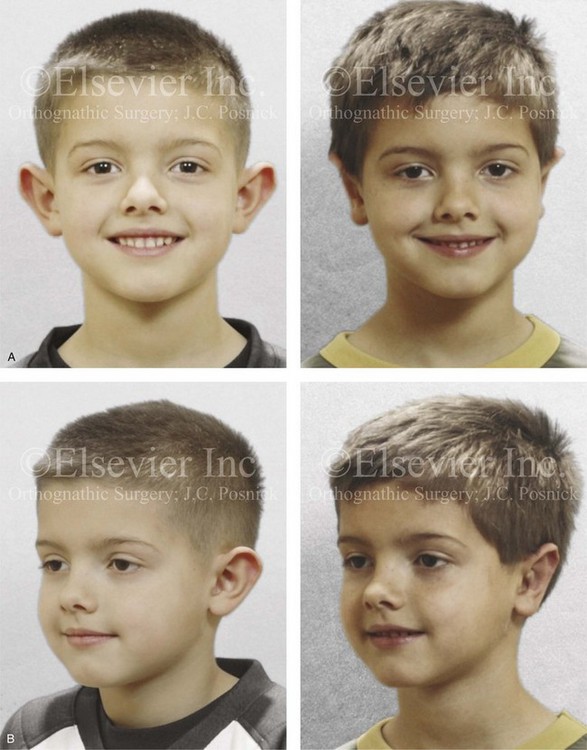

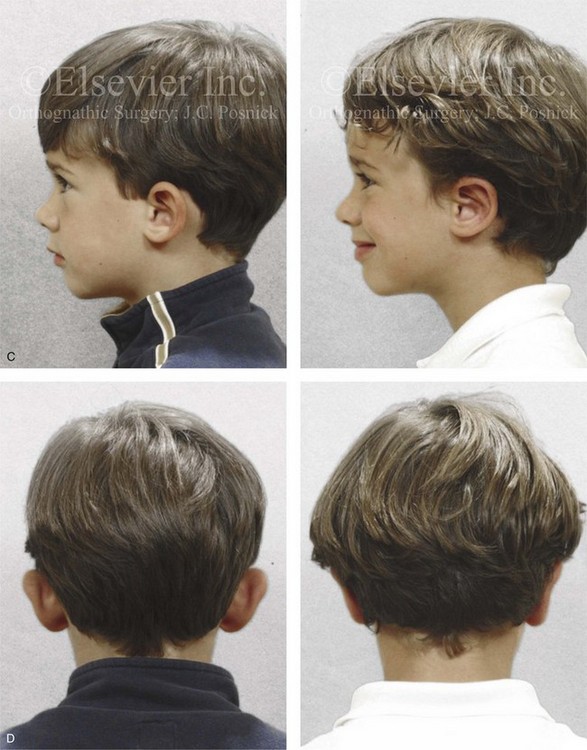

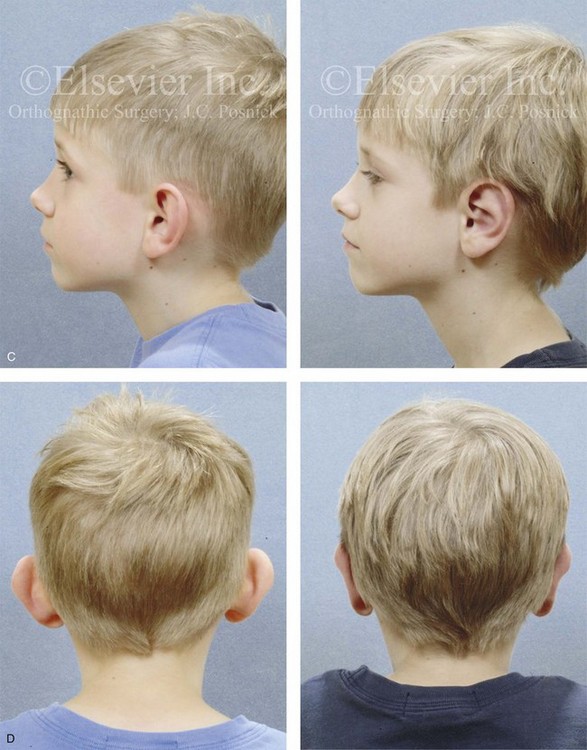

Figure 39-13 A 5-year-old boy with asymmetric prominent ears that are characterized by both conchal hypertrophy and deficient scaphal folding. He underwent elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures); and the improvement of the antihelical folds (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Posterior views before and after reconstruction.

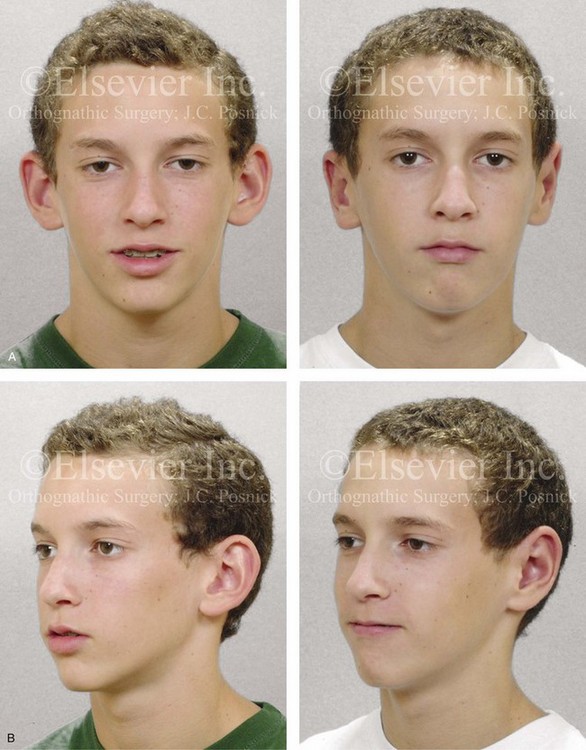

Figure 39-14 A 5-year-old boy with asymmetric prominent and cupped ears that are characterized by conchal hypertrophy, deficient scaphal folding, and a prominent earlobe. He underwent conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid sutures); improvement of the antihelical folding (Mustarde sutures); and earlobe set-back. A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Posterior facial views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-15 A 5-year-old boy with asymmetric prominent ears that are characterized by conchal hypertrophy and inadequate scaphal folding. He underwent conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and set-back (conchal–mastoid sutures); and deepening of the antihelical folding (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Posterior views before and after reconstruction.

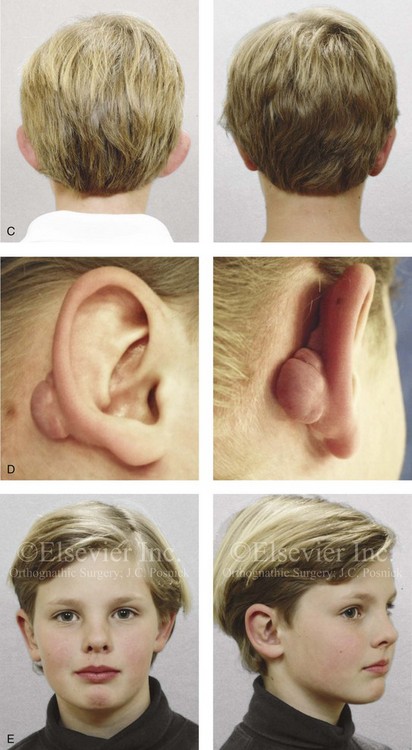

Figure 39-16 A 5-year-old boy with small and prominent ears that are characterized by the absence of scaphal folding and deep conchal hypertrophy. He underwent elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid sutures); and the creation of antihelical folds (Mustarde sutures). He returned 6 months after surgery with chronic irritation in the right postauricular fold. A stitch granuloma was debrided, and he went on to develop a localized hypertrophic scar in the same region. One year after surgery, the scar and inflammatory issue were excised, with primary closure. Healing was uneventful, and no other treatment was required. A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Profile views before and after reconstruction. C, Posterior views before and after reconstruction. D, Right ear postauricular view that shows the inflammatory tissue hypertrophic scar just before excision. E, Facial views 3 years after reconstruction and 2 years after scar tissue excision.

Figure 39-17 A 7-year-old boy with asymmetric prominent and cupped ears underwent reconstruction. This required limited elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures); improvement of the antihelical folding (Mustarde sutures); and earlobe set-back (tail of the helix–mastoid sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-18 An 11-year-old girl with asymmetric prominent ears that are characterized by conchal hypertrophy and inadequate scaphal folding underwent reconstruction. The procedures included conchal rotation and set-back (conchal–mastoid sutures) and the creation of improved antihelical folding (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. Note that there is a degree of incomplete correction or relapse of both the conchal and superior helix set-back of the right ear.

Figure 39-19 A high-school student with prominent ears that are characterized by conchal hypertrophy and deficient scaphal folding. She underwent elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid sutures); and the creation of an improved antihelical fold (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. Note the overly prominent antihelical crease of the right ear.

Figure 39-20 A high school student with prominent ears that are characterized by conchal hypertrophy and deficient scaphal folding. She underwent elliptical conchal resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid sutures); and the creation of an improved antihelical fold (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-21 A 9-year-old girl with a unilateral (right-side) prominent ear that is characterized by conchal hypertrophy and a lack of scaphal folding. She underwent a unilateral otoplasty. The ear cartilage was extremely thin and flexible. She underwent conchal rotation and set-back (conchal–mastoid sutures) and the creation of antihelical folding (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Right profile views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-22 A 9-year-old boy with malformed and asymmetric external ears who underwent reconstruction. His procedures included asymmetric elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures); the creation of the antihelical fold (Mustarde sutures); and earlobe set-back (soft-tissue sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Profile views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-23 A woman in her mid 20s with prominent ears that are characterized by a mild degree of conchal hypertrophy and deficient scaphal folding. She underwent elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation (conchal–mastoid sutures); and the creation of the antihelical fold (Mustarde sutures). She is shown before and just 2 weeks after surgery. At this stage of healing, residual edema and skin discoloration remain. A, Frontal views before and 2 weeks after surgery. B, Oblique facial views before and 2 weeks after surgery. C, Profile views before and 2 weeks after surgery.

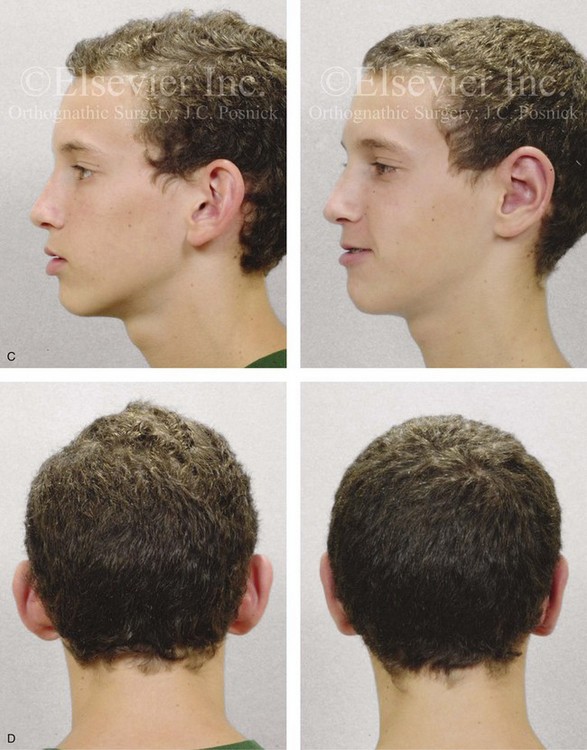

Figure 39-24 A high school student with prominent ears that are characterized primarily by conchal hypertrophy requested setback. He underwent conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid sutures); and stabilization of the antihelical folding (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Posterior views before and after reconstruction.

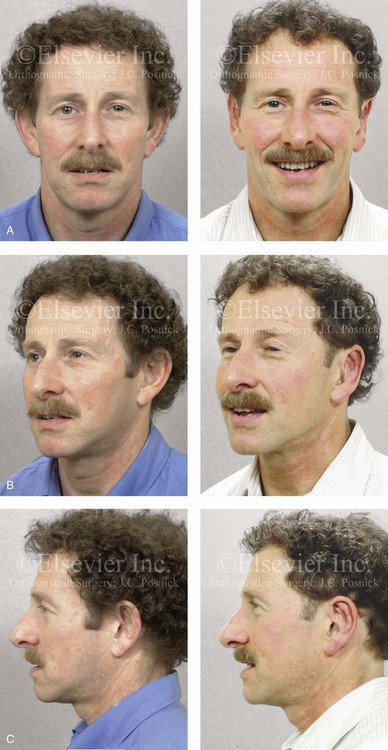

Figure 39-25 A middle-aged man with a lifelong history of prominent ears that are characterized by limited antihelical folding and a degree of conchal hypertrophy. He underwent conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal stabilization (conchal–mastoid sutures); and deepening of the scaphal folding (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-26 A high school student who was born with hemifacial microsomia underwent simultaneous jaw and external ear reconstruction (see Fig. 28-15). Although the ears are asymmetric in morphology and position, they were simply set back. The left ear underwent both conchal wall resection (posterior approach) and improvement of the scaphal fold (Mustarde stitches). The right ear required improvement of the scaphal fold (Mustarde stitches) and the placement of superior helix–mastoid sutures. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Right oblique facial views before and after reconstruction.

Figure 39-27 A 5-year-old child with Treacher Collins syndrome underwent zygomatic–orbital reconstruction and bilateral external otoplasty (see Fig. 27-11). The external ear procedures included elliptical conchal wall resection (posterior approach); conchal rotation and stabilization (conchal–mastoid suture); and the improvement of the antihelical folds (Mustarde sutures). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Worm’s-eye views before and after reconstruction.

In a recent study by Braun and colleagues, a consecutive series of patients (N = 84) who underwent otoplasty (suture technique) were given a health-related quality-of-life survey.6 The survey used was either the Glasgow Children’s Benefit Inventory (N = 41; 73.8% of study group) or the Glasgow Benefit Inventory (N = 21; 33.9% of study group). Both of these quality-of-life surveys have been validated for measuring the effect of plastic (aesthetic) operations on health-related quality of life. Sixty-two patients (73.8%) returned a valid questionnaire for analysis. For the study group, the main reasons for carrying out the ear set-back operations as reported by the patient and the family included teasing (42.6%); aesthetic impairment (39.3%); and reduced self-confidence (23%). The results of the study indicate that 100% of the adults were satisfied with their aesthetic results and that 90.5% would again decide in favor of the operation. Ninety-five percent of the parents of the children and 95.1% of the children themselves were satisfied with the aesthetic results. Ninety-seven percent of the parents and 92.7% of the children then also stated that they would again decide in favor of the operation. The authors also speculated that an individual’s reluctance to participate in certain social activities, if caused by reduced self-confidence as a result of the protruding ears, was more likely to remain constant with increased age. In other words, adults that had lived through the social ridicule of prominent ears for many years were more likely to retain reduced self-confidence even after successful ear set-back.

Complications and Suboptimal Aesthetic Results

Although the majority of patients state that they are satisfied with their otoplasty results and say that they would undergo such procedures again, complications and suboptimal results will always occur in a minority of cases.10,17,31,37,53,54,63

Non-Surgical Correction of Prominent Ears in the Newborn

Although the idea of “binding” the external ears in an attempt to correct abnormalities is not a new one, Matsuo and colleagues can be credited with examining the efficacy of doing so in newborns.40 Byrd and colleagues convincingly demonstrated that there are particular auricular deformities in the newborn that are amenable to molding back toward normal.9 In their publication, the types of deformities that can be most effectively treated and details concerning methods of molding are discussed. Auricular deformations are characterized by a misshapen but fully developed pinna.65,66 Ear molding techniques are best suited for deformations rather than malformations.8,12,29,36,41,43,45,59,68,71 Interestingly, approximately one third of the ear deformations that are present at the time of birth self-correct during the first week of life. The patterns of deformation that are frequently seen include the following: prominent/cupped ears; lidded/lopped ears; Stahl (or Spock) ears; helical rim deformities (with an absent or deficient rim); and conchal crus deformities.49,51,58 Byrd and colleagues found that birth deformations of the auricle more often than not involve the upper third of the ear, with incomplete formation of the superior limb of the triangular fossa being a frequent finding. This leads to a helical rim scapha deformation. The authors stressed the importance of accomplishing three key molding forces to correct the majority of these ear deformations in newborns:

1. A stent or conformer that rests along the retroauricular sulcus and that is in alignment with the antihelix is placed.

2. A second conformer that is curved to match the natural shape of the helical rim is used. It is placed anteriorly but with force directed against the scapha. The anterior conformer is carefully located to avoid excess direct pressure against the posterior conformer for the avoidance of skin necrosis.

3. As the helix is retracted, the molding technique is also used to expand the rim to its full dimension.

The authors described good to excellent results in 90% of the newborns whose external ear deformities were treated in this way. Complications were seen in only approximately 5% of patients and were mostly characterized as localized skin excoriations. The authors recommend withholding ear-molding therapy until the end of the first week to identify those infants whose ears spontaneously self-correct soon after birth. It is believed by most that, for treatment to be effective, it should be instituted by the second or (at most) third week of life. Only approximately half of the infants treated by Byrd and colleagues after 3 weeks of age had good outcomes. The reason for this is believed to be related to the level of hyaluronic acid, which is an important component of ear cartilage.27 Hyaluronic acid is increased by estrogen and believed to be responsible for the malleable nature of the neonatal ear. The circulating estrogen levels are known to decrease rapidly to levels that are similar to those of older children by 6 weeks of age.33 It is also known that, with breast-feeding, the maternal transfer of estrogen extends the time frame of higher hyaluronic acid levels, which likely explains the variations in the effectiveness of ear molding in some children; this may also leave the ears prone to relapse after molding treatment is stopped unless the result is maintained.

References

1. Adamson, JE, Horton, CE, Crawford, HH. The growth pattern of the external ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965; 36:466.

2. Adamson, PA, McGraw, BL, Tropper, GJ. Otoplasty: Critical review of clinical results. Laryngoscope. 1991; 101:883.

3. Barnes, WE, Morris, FA. Otoplasty: An improved technique. South Med J. 1966; 59:681.

4. Bauer, BS, Margulis, A, Song, DH. The importance of conchal resection in correcting the prominent ear. Aesthet Surg J. 2005; 25:72–79.

5. Beam, RB. Some characteristics of the external ear of American whites, American Indians, American Negros, Alaskan Eskimos, and Filipinos. Am J Anat. 1915; 18:201.

6. Braun, T, Hainzinger, T, Stelter, K, et al. Health-related quality of life, patient benefit, and clinical outcome after otoplasty using suture techniques in 62 children and adults. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 126:2115–2124.

7. Brent, B. Panel: Aesthetic otoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 1992; 12:4.

8. Brown, FE, Colen, LB, Addante, RR, Graham, JM, Jr. Correction of congenital auricular deformities by splinting in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1986; 78:406–411.

9. Byrd, HS, Langevin, CJ, Ghidoni, LA. Ear molding in newborn infants with auricular deformities. J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 126:1191–1200.

10. Calder, JC, Naasan, A. Morbidity of otoplasty: A review of 562 consecutive cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1994; 47:170.

11. Caouette-Laberge, L, Guay, N, Bortoluzzi, P, Belleville, C. Otoplasty: Anterior scoring technique and results in 500 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:504.

12. Dancey, A, Jeynes, P, Nishikawa, H. Acrylic ear splints for treatment of cryptotia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 115:2150–2152.

13. Davis, J. Prominent ears. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:471.

14. Davis, J. The prominent ear: Sequel repair. In: Aesthetic and Reconstructive Otoplasty. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987:129–187.

15. Dieffenbach LF: Die operative chirugiem: FA Brockhaus, 1845.

16. Elliott, RA, Hoehn, JG. Otoplasty for prominent ears: A composite approach [microfiche]. Int J Aesthet Plast Surg. 1972.

17. Elliott, RA. Complications in the treatment of prominent ears. Clin Plast Surg. 1979; 5:479.

18. Elliott, RA. Otoplasty: A combined approach. Clin Plast Surg. 1990; 17:2.

19. Ely, E. An operation for prominence of the auricles. Arch Otolaryngol. 1881; 10:97.

20. Farkas, LG. Anthropometry of normal and anomalous ears. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:401.

21. Farkas, LG, Posnick, JC, Hreczko, T. Anthropometric growth study of the ear. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992; 29(4):324–329.

22. Furnas, DW. Correction of prominent ears by conchamastoid sutures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 42:189.

23. Furnas, DW. Correction of prominent ears with multiple sutures. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:491.

24. Furnas, DW. Otoplasty for prominent ears. Clin Plast Surg. 2002; 29:273.

25. Gibson, TW, Davis, W. The distortion of autogenous cartilage grafts: Its cause and prevention. Br J Plast Surg. 1958; 10:257.

26. Goulian, D, Conway, H. Prevention of persistent deformity of the tragus and lobule by modification of Luckett’s technique of otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960; 26:399.

27. Hardingham, TE, Muir, H. The specific interaction of hyaluronic acid with cartilage proteoglycans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972; 279:401–405.

28. Hinderer, UT, del Rio, JL, Fregenal, FJ. Otoplasty for prominent ears. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1987; 11:63.

29. Hirose, T, Tomono, T, Yamamoto, K. Non-surgical correction for cryptotia using simple apparatus. In: Foneseca J, ed. Transactions of the 7th International Congress of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Rio de Janeiro, 1979. Sao Paulo, Brazil: Catgraf, 1980.

30. Hirose, T, Tomono, T, Matsuo, K, et al. Cryptotia: Our classification and treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1985; 38:352–360.

31. Jeffery, SL. Complications following correction of prominent ears: An audit review of 122 cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1999; 52:588.

32. Kaye, BL. A simplified method for correcting the prominent ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967; 40:44.

33. Kenny, FM, Angsusingha, K, Stinson, D, Hotchkiss, J. Unconjugated estrogens in the perinatal period. Pediatr Res. 1973; 7:826–831.

34. Klockars, T, Rautio, J. Embryology and epidemiology of microtia. Facial Plast Surg. 2009; 25:145–148.

35. Kösling, S, Omenzetter, M, Bartel-Friedrich, S. Congenital malformations of the external and middle ear. Eur J Radiol. 2009; 69:269–279.

36. Kurozumi, N, Ono, S, Ishida, H. Non-surgical correction of a congenital lop ear deformity by splinting with Reston foam. Br J Plast Surg. 1982; 35:181–182.

37. Lentz, AK, Plikaitis, CM, Bauer, BS. Understanding the unfavorable result after otoplasty: An integrated approach to correction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 128:536–544.

38. Luckett, WH. A new operation for prominent ear based on the anatomy of the deformity. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910; 10:635.

39. Macgregor, F. Ear deformities: Social and psychological implications. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:347.

40. Matsuo, K, Hirose, T, Tomono, T, et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in the early neonate: A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984; 73:38–51.

41. Matsuo, K, La Rusca, I, Molea, G. Non-surgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 1990; 17:383–395.

42. McDowell, AJ. Goals in otoplasty for protruding ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 41:17.

43. Merlob, P, Eshel, Y, Mor, N. Splinting therapy for congenital auricular deformities with the use of soft material. J Perinatol. 1995; 15:293–296.

44. Morestin, MH. De la reposition et du plissement cosmetiques du pavillon de l’oreille. Rev Orthop. 1903; 4:289.

45. Muraoka, M, Nakai, Y, Ohashi, Y, et al. Tape attachment therapy for correction of congenital malformations of the auricle: Clinical and experimental studies. Laryngoscope. 1985; 95:167–176.

46. Mustarde, JC. The correction of prominent ears by using simple mattress sutures. Br J Plast Surg. 1963; 16:170.

47. Mustarde, JC. The treatment of prominent ears by buried mattress sutures: A ten year survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967; 39:382.

48. Mustarde, JC. Correction of prominent ears using buried mattress sutures. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:459.

49. Nakajima, T, Yoshimura, Y, Kami, T. Surgical and conservative repair of Stahl’s ear. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1984; 8:101–107.

50. Owens, N, Delgado, DD. The management of outstanding ears. South Med J. 1965; 58:32.

51. Park, C. Correction of cryptotia using an external stretching device. Ann Plast Surg. 2002; 48:534–538.

52. Posnick, JC. Aesthetic alteration of prominent ears: Evaluation and surgery. In: Posnick JC, ed. Craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery in children and young adults. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 2000:1143–1153.

53. Reynaud, JP, Gary-Bobo, A, Mateu, J, Santoni, A. Chondrites postoperatories de l’oreille externe: 2 cases from a series of 200 cases (387 otoplasties). Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1986; 31:170.

54. Rigg, BM. Suture materials in otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979; 63:409.

55. Rodriguez-Champs, S. Our procedure for integral aesthetic otoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997; 21:332.

56. Rogers, BO. Ely’s 1881 operation for correction of protruding ears. A medical “first. ”. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 42:584.

57. Rubin, LR, Bromberg, BE, Walden, RH, et al. An anatomic approach to the obtrusive ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1962; 29:360.

58. Schonauer, F, La Rusca, I, Molea, G. Non-surgical correction of deformational auricular anomalies. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009; 62:876–883.

59. Smith, W, Toye, J, Reid, A, Smith, R. Nonsurgical correction of congenital ear abnormalities in the newborn: Case series. Paediatr Child Health. 2005; 10:327–331.

60. Stark, RB, Saunders, DE. Natural appearance restored to the unduly prominent ear. Br J Plast Surg. 1962; 15:385.

61. Stenstrom, SJ. A “natural” technique for correction of congenitally prominent ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960; 26:640.

62. Stenstrom, SJ, Heftner, J. The Stenstrom otoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:465.

63. Szychta, P, Orfaniotis, G, Stewart, KJ. Otoplasty: An algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012; 130:907.

64. Tan, KH. Long-term survey of prominent ear surgery: A comparison of two methods. Br J Plast Surg. 1986; 39:270.

65. Tan, ST, Shibu, M, Gault, DT. A splint for correction of congenital ear deformities. Br J Plast Surg. 1994; 47:575–578.

66. Tan, ST, Abramson, DL, MacDonald, DM, Mulliken, JB. Molding therapy for infants with deformational auricular anomalies. Ann Plast Surg. 1997; 38:263–268.

67. Tolleth, H. Artistic anatomy, dimensions, and proportions of the external ear. Clin Plast Surg. 1978; 5:337.

68. Ullmann, Y, Blazer, S, Ramon, Y, et al. Early nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002; 109:907–913.

69. Webster, CV. The tail of the helix as a key to otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969; 44:455.

70. Whitaker, LA, Yaremchuk, MJ, Posnick, JC. A method for repositioning the external ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 86(1):128–132.

71. Yotsuyanagi, T, Yokoi, K, Urushidate, S, Sawada, Y. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in children older than early neonates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 101:907–914.

72. Young, F. The correction of abnormally prominent ears. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1944; 78:541.