Chapter 38 Adverse reactions to complementary medicines (CMs)

Introduction

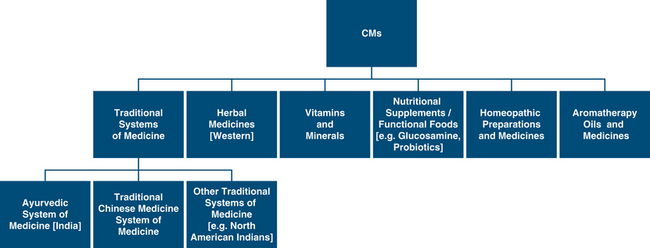

The definition of adverse drug reaction is defined as a ‘response to a medicine which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in man’.1 Overall the risk associated with CMs is generally low considering widespread community use. In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) define CMs as ‘medicinal products containing herbs, vitamins, minerals, and nutritional supplements, homoeopathic medicines and certain aromatherapy products are referred to as ‘complementary medicines’.2 These are regulated as medicines under the Therapeutics Goods Act 1989i (the Act). CMs also comprise traditional medicines, including traditional Chinese medicines, Ayurvedic medicines and Australian indigenous medicines. See Figure 38.1 for classes of CMs.

Figure 38.1 Classes of CMs encountered in Australia

(Source: adapted and modified from TGA report http://www.tga.gov.au/DOCS/pdf/cmreport.pdf)

According to the TGA, data from adverse events reported to the Australian Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC) arising from the use of listed CMs from 2004 to 2008, for example, shows that there were a total of 656 total reports where a CM was the sole suspected possible, probable or certain cause of an adverse patient reaction, with 7 possible death outcomes associated with a CM. During the same period there were 38 337 cases where a medicine (prescription, over-the-counter medication and other products registered on the Australian register of therapeutic goods (ARTG) included registered rather than listed CMs) was the sole suspected possible, probable or certain cause of an adverse patient reaction, and there were 1014 possible death outcomes.3 In many cases the contribution of the suspected medicine to the death is uncertain, however, based on the information reported it is not possible to entirely exclude the possibility that the suspected medicine contributed to the fatal outcome.

Based on these statistics, the level of reporting for CMs is relatively low compared with pharmaceuticals, considering the widespread usage and the complex diversity of CMs that can be found in Australia, the US and other countries. There may be a number of factors contributing to this, other than having a relatively favourable safety profile (not necessarily efficacy). Other factors include significant under-reporting due to patients failing to communicate adverse events to their medical practitioner and their use of CMs, and medical and allied health practitioners failing to report adverse events to the relevant adverse reporting systems available in each country such as ADRAC in Australia or the FDA in the United States. For example the hepatotoxicity associated with herbal remedies, and naturally occurring plants is extensively under-reported. Hepatotoxicity under-reporting may relate to undetectable subclinical liver disease with mildly abnormal liver chemistry tests thereby endowing many medicinal plants and herbal medicines with a potential for hepatotoxicity with extended use or with overdosing (see Table 38.1).

Table 38.1 Hepatotoxicity of medicinal plants and herbal medicines

| Potentially hepatotoxic | Unlikely hepatotoxic |

|---|---|

| Ackee fruit Mediterranean glue thistle/Atractylis gummifera Azadirachta indica Bajiaolian Berberis vulgaris Black cohosh/Cimicifuga racemosa Impila/Callilepsis laureola Camphor Cascara sagrada Carp gallbladder Senna/Cassia angustifolia Greater celandine/Chelidonium majus Chinese herbal medicines Cocaine/Erythroxylon coca Sassafras/Sassafras albidum |

Chamomille/Anthemis nobilis

Cranberry/Vaccinium macrocarpon

Dandelion root/Taraxacum Officinale

Feverfew/Tanacetum parthenium

Garlic/Allium sativum

Ginger/Zingiber Officinale

Gingko Biloba

Ginseng/Panax ginseng

Goldenseal/Hydrastis canadensis

Peppermint/Mentha piperita

St John’s Wort/Hypericum perforatum

Saw Palmetto/Serenoa repens

(Source: adapted and modified from Steadman,5 Chiturri & Farrell,6 Ernst,7 Teschke et. al.,8 and Schiano9)

Knowledge of CM adverse reactions

From the Australian National Prescribing Service (NPS) study, it is clear there is an urgent need for medical practitioners such as General Practitioners to learn more about adverse reactions with CMs.4 About 40% of general practitioners reported having minimal or no knowledge about black cohosh and ginkgo biloba, and less than 40% of the surveyed GPs were aware of some potential side-effects and drug–CM interactions of ginkgo biloba, glucosamine and black cohosh.4 Only 38% of GPs were aware that black cohosh has been linked to liver damage despite an ADRAC report published in 2005.2, 10 This highlights a concern that needs to be addressed through better education about risks associated with CMs and the need to report adverse reports for CMs, especially as there is widespread community use with up to one-quarter of Australians using at least 1 medicinal herb and two-thirds are using some form of CM within the last 12 months of national surveys.11, 12

Types of adverse reactions

Pharmacodynamic versus pharmacokinetic reactions

Medicine interactions can also be described as pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic. Pharmacodynamic reactions are usually complex where medicines can interfere with absorption, metabolism by enzymes such as cytochrome P450 and renal excretion affecting another medicine. Pharmacokinetic interactions involve additive of similar medicines or a cancelling effect.13

Common interactions

Most common potential interactions were for pharmaceuticals: aspirin, warfarin, ticlodipine, plus CMs: garlic, gingko, glucosamine, or fish oil potentially resulting in increased risk of bleeding.14

Extemporaneous herbs such as Ayurvedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine may be contaminated by heavy metals such as lead, arsenic and mercury, potentially causing metal toxicity15–18 or contaminated with pharmaceuticals such as steroids or hormones, particularly those imported from overseas countries that have poor regulatory guidelines.19

For more detailed information about herb–nutrient–drug interactions, please refer to Chapter 37. A number of papers have explored potential herb drug interactions but adequate research and understanding in this area is still lacking.20–25

Risk factors for adverse reactions

It is important to note that elderly, children, pregnant and lactating women may respond differently to adverse reactions as the physiology and metabolism varies with their weight, age, and many other factors that affect medication dosages.26 The elderly are particularly prone to adverse reactions as they are more likely to suffer a comorbid disease such as a chronic disease, have some degree of renal and hepatic impairment, low muscle mass, are prone to dehydration especially at times of suffering diarrhoea, and are often taking other medication which puts them at higher risk of herb–drug interactions. Adverse reactions can also be determined by genetic differences which explain why some populations are more prone to reactions. This is known as pharmacogenetics. This phenomenon is recognised with pharmaceuticals but not well recognised with CMs to date.27

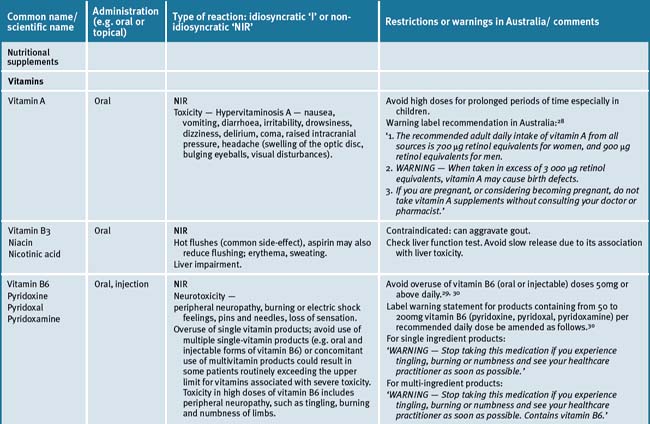

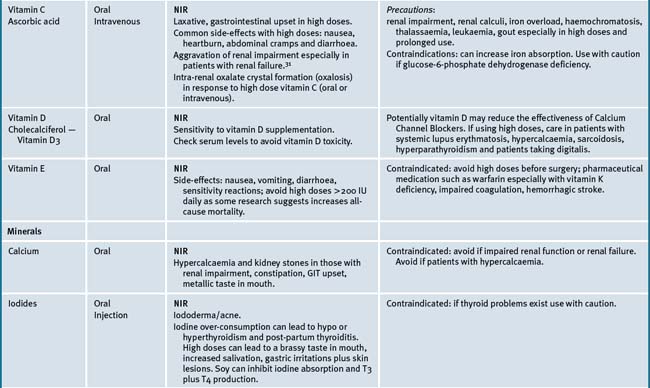

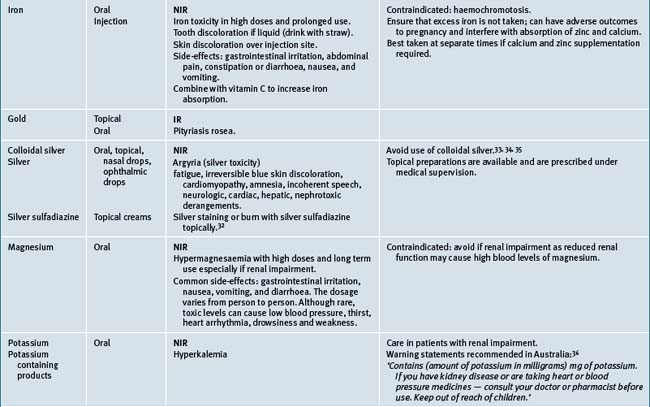

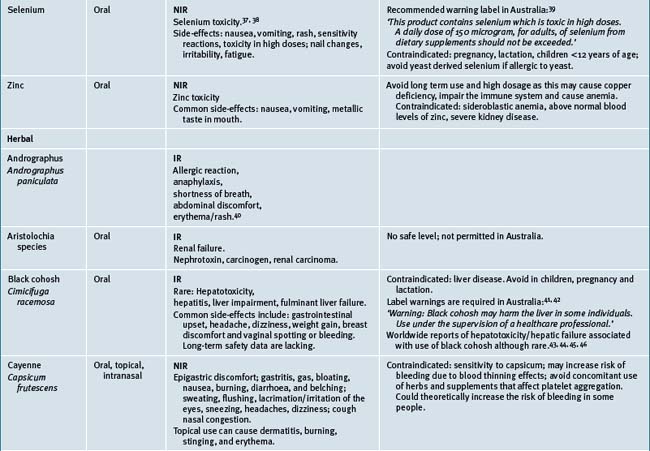

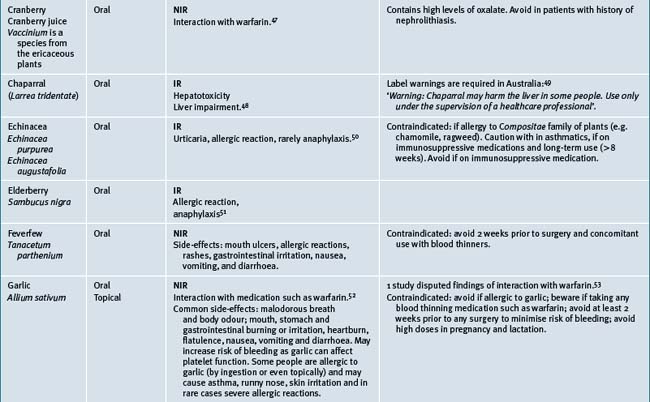

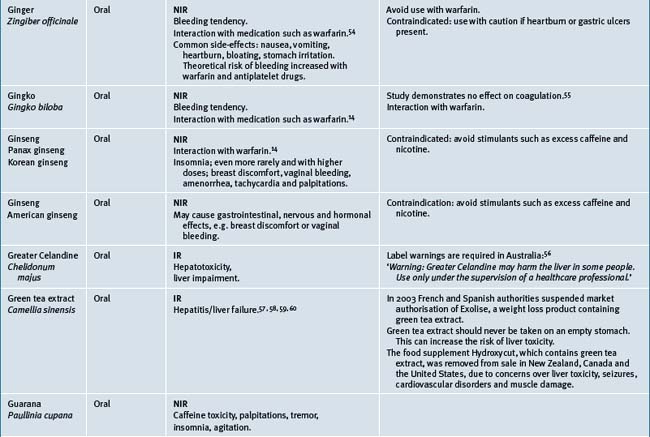

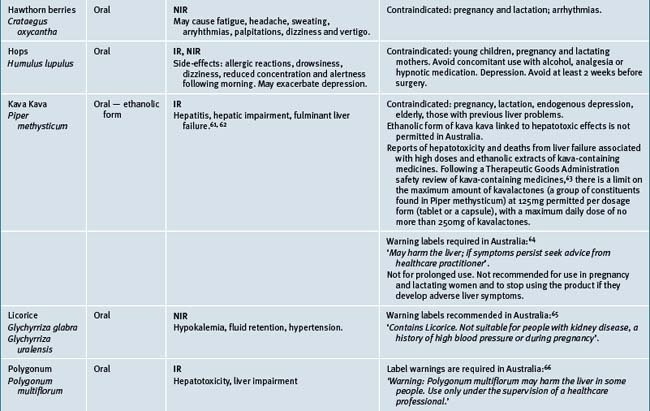

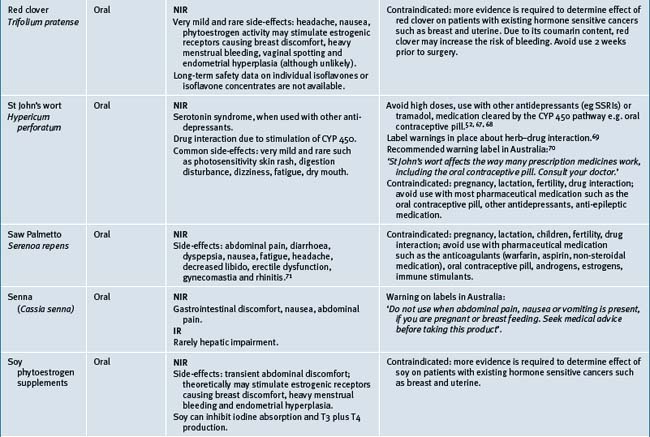

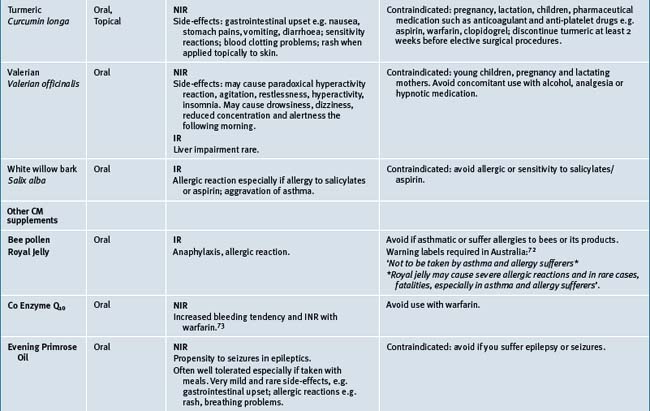

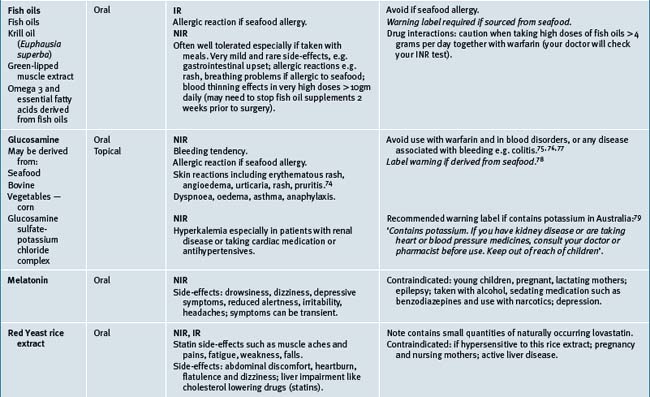

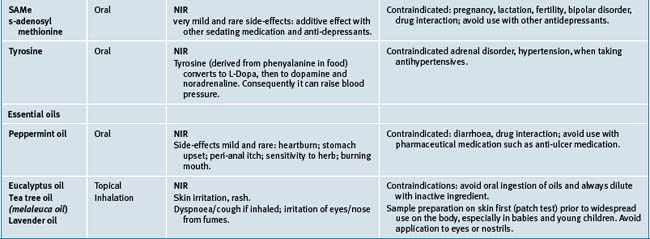

Table 38.2 summarises likely adverse reactions reported in the literature and to adverse reporting bodies for CMs at the time of writing this chapter.

Reporting adverse events

It is imperative that all health practitioners (medical and non-medical) report any suspected adverse reactions or interactions to medicines/pharmaceuticals, including CMs, over-the-counter medicines, any traditional or alternative remedies and vaccines, including those suspected of causing death, hospital admission, requiring more treatment and investigations or suspected birth defects if a mother takes a medicine during pregnancy.80 These reports are analysed by experts using the World Health Organization (WHO) causality assessment algorithm to determine level of causality of a suspected medicine(s) (see Who algorithm below). Reporting of adverse reactions provides information that can be gathered for any emerging medicine safety issues and allows further action in each country or internationally to be taken if necessary. Action may include restricting use of the medicine or enforce relevant label warnings and for media alerts to warn the community of concerns.

Reporting systems are in place in many developed countries. These are summarised in Table 38.3.

| Country and publications | Mechanism for reporting |

|---|---|

| Australia Medicines Safety Update (having replaced ADRAC bulletins) in Australian prescriber regularly report common or serious adverse reactions to CMs. To subscribe, go to: www.tga.gov.au/adr/msn/msu1006.htm |

Reports of suspected adverse drug reactions are best made by using a prepaid reporting form (‘blue card’) which is available from the website: http://www.tga.gov.au/adr/bluecard.pdf or from the Adverse Drug Reactions Unit of the Office of Safety Monitoring, phone no: 02-6232-8744. Reports can also be submitted electronically, by going to the TGA website http://www.tga.gov.au and clicking on the ‘report problems’ tab on the left, by fax: 02-6232-8392, or email: ADR.Reports@tga.gov.au,or by filling in the blue card and posting to ADRAC. Ensure you provide the AUST-L or AUST-R for the CM which is found on the label. This helps the TGA identify the product and its ingredients. |

| New Zealand Prescriber update bulletin MEDSAFE — New Zealand medicines and medical devices safety authority, a business unit of the ministry of health. Online. Available: www.medsafe.govt.nz Healthcare professionals with any questions on access or availability of the electronic reporting tool should contact BPAC on (03) 477 5418. Prescribers are encouraged to report reactions to the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM). An electronic version of Prescriber Update is available at: www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/PUarticles.asp To receive Prescriber Update electronically, register at: www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs.htm Data sheets, consumer medicine information, media releases, medicine classification issues, and adverse reaction forms can be found at: www.medsafe.govt.nz |

Report all adverse events occurring with IMMP medicines to: IMMP, NZ Pharmacovigilance Centre, PO Box 913, Dunedin 9054. Use the reporting form provided with each edition of MIMS New Ethicals or download it from either the NZ Pharmacovigilance Centre or Medsafe websites: www.otago.ac.nz/carm or www.medsafe.govt.nz/Profs/adverse.htm Further information on IMMP is available at: http://carm.otago.ac.nz/index.asp?link=immp Please report all cases of the following adverse reactions to: CARM, NZ Pharmacovigilance Centre, PO Box 913, Dunedin 9054. Use the reporting form provided with each edition of MIMS New Ethicals, or download the form from the CARM or Medsafe web sites: www.otago.ac.nz/carm or www.medsafe.govt.nz/Profs/adverse.htm |

| Canada Canada Vigilance Program Phone: 866 234-2345 Fax: 866 678-6789 Online: www.healthcanada.gc.ca/medeffect Health Canada Marketed Health Products Directorate AL 0701C Ottawa ON K1A 0K9 Tel: 613 954-6522 Fax: 613 952-7738 |

Report an adverse reaction to the Canada Vigilance Program:

The form and postage-paid label are available at www.healthcanada.gc.ca/medeffect or by calling 1-866-234-2345. |

| United Kingdom Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (UK) www.mhra.gov.uk/mhra/drugsafetyupdate Sign up to receive an email alert when a new issue is published: email registration@mhradrugsafety.org.uk The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency is the government agency which is responsible for ensuring that medicines and medical devices work, and are acceptably safe. The Commission on Human Medicines gives independent advice to ministers about the safety, quality, and efficacy of medicines. The Commission is supported in its work by expert advisory groups that cover various therapeutic areas of medicine. |

The Yellow Card Scheme collects information on suspected adverse drug reactions in the UK. See www.yellowcard.gov.uk |

| United States MedWatch Website is available to the public to voluntarily report a serious adverse event, product quality problem, product use error, or therapeutic inequivalence/failure that they suspect is associated with the use of an FDA-regulated drug, biologic, medical device, dietary supplement or cosmetic. Food and Drug Administration (USA) Contact details: 10903 New Hampshire Ave Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002 or by telephone. The main FDA phone number for general inquiries: 1-888-INFO-FDA (1-888-463-6332) Website: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/ContactFDA/default.htm |

Reporting an adverse reaction: Phone 1-800-332-1088 FAX: 1-800-FDA-0178 Electronic reporting: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch/medwatch-online.htm Postage: MedWatch 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20852-9787 |

| Europe/World Health Organization (WHO) Data from the WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring WHO definition of traditional medicine (TM). The Uppsala Monitoring Centre (the UMC) is the fieldname of the WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, responsible for the management of the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring. An independent centre of scientific excellence, the UMC, offers products and services, derived from the WHO database of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) reported from member countries of the WHO program. |

The UPPSALA Monitoring CENTRE (Sweden) Mail address: Box 1051 SE-751 40 Uppsala Sweden Visiting address only: Bredgränd 7 SE-753 20 Uppsala Sweden Telephone: +46 18 65 60 60 Fax: +46 18 65 60 88 Email: (general enquiries) info@who-umc.org (sales and marketing enquiries) info@umc-products.com (Drug Dictionary enquires) drugdictionary@umc-products.com Internet: www.who-umc.org |

| Germany Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, Bundesinstitut fu¨r Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM) The BfArM is a federal institute within the portfolio of the Federal Ministry of Health. Website: http://www.bfarm.de/EN/Home/homepage__node.html |

Address: Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte Kurt-Georg-Kiesinger-Allee 3 D-53175 Bonn, Germany Telephone: +49 (0)228 99-307-0 Telefax: +49 (0)228 99-307-5207 Email: poststelle@bfarm.de |

World Health Organization causality assessment

Use the following WHO assessment of adverse reports by experts to determine the level of causality of a suspected medicine(s).81

Causality Assessment Algorithm

1 Safety Monitoring of Medicinal Products. Guidelines for setting up and running a Pharmacovigilance Centre. London: Uppsala Monitoring Centre-WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring. EQUUS; 2002. Online. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_EDM_QSM_2002.2.pdf (accessed 14 Sept 2009)

2 Australian Government. Department of Health and Ageing. Therapeutic Goods Administration. The regulation of complementary medicines in Australia — an overview. April 2006. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/cm/cmreg-aust.htm (accessed 14 April 2009)

3 Statistics provided by the Office of Medicines Safety Monitoring at the Therapeutic Goods Administration, 25 March 2009. Office of Medicines Safety Monitoring adrac@tga.gov.au, Phone: 1800 044 114.

4 Brown J., Morgan T., Adams J., Grunseit A., Toms M., Roufogalis B., Kotsirilos V., Pirotta M., Williamson M. Complementary Medicines Information Use and Needs of Health Professionals: General Practitioners and Pharmacists. Sydney: National Prescribing Service; December 2008.

5 Stedman C. Herbal hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:195.

6 Chitturi S., Farrell G.C. Herbal hepatotoxicity: an expanding but poorly defined problem. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1093.

7 Ernst E. Harmless herbs? A review of the recent literature. Am J Med. 1998;104:170.

8 Teschke R., Schwarzenböck A., Hennermann K.H. Toxic liver disease due to drugs, herbs and dietary supplements: diagnostic approaches. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45(2):195-208.

9 Schiano T.D. Hepatotoxicity and complementary and alternative medicines. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:453-473.

10 Black cohosh and liver toxicity — an update. Aust Adv Drug Reactions Bull 26(3). Jun 2007;26(3):11.

11 Zhang A.L., Story D.F., Lin V., Vitetta L., Xue C.C. A population survey on the use of 24 common medicinal herbs in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2008;17:1006-1013.

12 Williamson M., Tudball J., Toms M., Garden F., Grunseit A. Information Use and Needs Of Complementary Medicines Users. Sydney: National Prescribing Service; October 2008. Online. Available: www.nps.org.au/research_and_evaluation/research/current_research/complementary_medicines/cms_users_research#KF (accessed 14 April 2009)

13 Bryant L., Fishman T. Clinically important drug-drug interactions and how to manage them. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2009;1(2):150-151.

14 Elmer G.W., Lafferty W.E., Tyree P.T., Lind B.K. Potential interactions between complementary/alternative products and conventional medicines in a Medicare population. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1617-1624.

15 Saper R.B., Kales S.N., Paquin J., et al. Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2868-2873.

16 Traditional Indian (Ayurvedic) and Chinese medicines associated with heavy metal poisoning. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2007;26(1):2.

17 Saper R.B., Phillips R.S., Sehgal A., et al. Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured Ayurvedic medicines sold via the internet. JAMA. 2008;300:915-923.

18 Cooper K., Noller B., Connell D., Yu J., et al. Public Health Risks from Heavy Metals and Metalloids Present in Traditional Chinese Medicines. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. Current issues. 2007;70:1694-1699.

19 Adverse reactions to complementary medicines. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2005;24:2.

20 Hu Z., Yang X., Ho P.C., et al. Herb-drug interactions: a literature review. Drugs. 2005;65:1239-1282.

21 Skalli S., et al. Drug interactions with herbal medicines. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:679-686.

22 Horn J.R., Hansten P.D., Lingtak–Neander C.A. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;41:674-680.

23 Bryant L., Fishman T. Clinically important drug–drug interactions and how to manage them. J Prim Health Care. 2009:1. Online. Available: www.globalfamilydoctor.com/search/GFDSearch.asp?itemNum=10333 (accessed 14 April 2009)

24 Charrois T.L., Hill R.L., Vu D., et al. Community identification of natural health product–drug interactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1124-1129.

25 Sood A., Sood R., Brinker F.J., et al. Potential for interactions between dietary supplements and prescription medications. Am J Med. 2008;121:207-211.

26 Beggs S.. Adverse drug reactions in children. Paediatrics & Child Health in General Practise. 2009;5:12-13. April

27 Howland R.H. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 2009;32(3):265-270.

28 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/html/cmec/cmecdr63.htm (accessed 5 Oct 2009)

29 High-dose vitamin B6 may cause peripheral neuropathy. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2008;27(4):14-16.

30 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi66.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

31 McHugh G.J., Graber M.L., Freebairn R.C. Fatal vitamin C-associated acute renal failure. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008;36:585-588.

32 Fuller F.W. The side-effects of silver sulfadiazine. J Burn Care Res. 2009 May–Jun;30(3):464-470.

33 Wan A.T., Conyers R.A., Coombs C.J., Masterton J.P. Determination of silver in blood urine and tissues of volunteers and burn patients. Clin. Chem. 1991; Oct;37(10 Pt 1):1683-1687.

34 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Dangers associated with chronic ingestion of colloidal silver. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2007;26(5):19.

35 White J.M., Powell A.M., Brady K., Russell-Jones R. Severe generalized argyria secondary to ingestion of colloidal silver protein. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2003;28(3):254-256.

36 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi60.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

37 See K.A., Lavercombe P.S., Dillon J., Ginsberg R. Accidental death from acute selenium poisoning. MJA. 2006;185:388-389.

38 Guang-Qi Y., Yi-Ming X. Studies on Juman Dietary Requirements and Safe Range of Dietary Intakes of Selenium in China and Their Application in the Prevention of Related Endemic Diseases. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences. 1995;8:187-201.

39 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/html/cmec/cmecdr63.htm (accessed 5 Oct 2009)

40 Farah M., Meyboom R., Ploen M. Acute hypersensitivity reactions to andrographis paniculate containing products, as reported in International Pharmacovigilence. Drug Safety. 2008;31:913-914.

41 Agency Search Australia. Online. Available: http://agencysearch.australia.gov.au/search/search.cgi?query=BLACK+COHOSH+WARNING+LABEL&collection=agencies&profile=tga

42 Hepatotoxicity with black cohosh. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2006;25(2):6.

43 The European Medicines Agency 2008. Online. Available: www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/paediatrics/000006-PIP01-07.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

44 Whiting P.W., Clouston A., Kerlin P. Black cohosh and other herbal remedies associated with acute hepatitis. MJA. 2002;177:440-441.

45 Lantos S., Jones R.M., Angus P.W., Gow P.J., et al. Acute liver failure associated with the use of herbal preparations containing black cohosh. MJA. 2003;197:390-391.

46 Chow E.C., Teo M., Ring J.A., Chen J.W. Lessons from practice: liver failure associated with the use of black cohosh for menopausal symptoms. MJA. 2008;188:420-422.

47 Suvarna R., Pirmohamed M., Henderson L. Possible interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice. BMJ. 2003;327:1454.

48 Kauma H., Koskela R., Mäkisalo H., et al. Toxic acute hepatitis and hepatic fibrosis after consumption of chaparral tablets. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(11):1168-1171.

49 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi50.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

50 Saunders P.R., Smith F., Schusky R.W. Echinacea purpurea L. in children: safety, tolerability, compliance, and clinical effectiveness in upper respiratory tract infections. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:1195-1199.

51 Forster Wadl E., Marchetti M., Scholl I., et al. Type 1 allergy to elderberry (Sambucus nigra) is elicited by a 33.2 kDa allergen with significant homology to ribosomal inactivating proteins. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:1703-1710.

52 Fugh-Berman A. Herb-drug interactions. Lancet. 2000;355:134-138.

53 Smith L., Ernst E., Ewings, et al. What affects anticoagulation control in patients taking warfarin? British Journal of General Practice. 2009;59:590-594.

54 Shalansky S., Lynd L., Richardson K., et al. Risk of warfarin-related bleeding events and supratherapeutic International Normalised Ratios associated with complementary and alternative medicine: a longitudinal analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1237-1257.

55 Jiang X., Williams K.M., Liauw W.S., et al. Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59(4):425-432.

56 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/html/celandine.htm

57 Sarma D.N., et al. Safety of Green Tea extracts, a systematic review by the US Pharmacopoeia. Drug Safety. 2008;31(6):469-484.

58 Molinari, et al. Acute Liver failure induced by green tea extracts: case report and review of the literature. Liver Transplantation. 2006;12:1892-1895..

59 Sarma D.N., Barrett M.L., Chavez M.L., et al. Safety of green tea extracts: a systematic review by the US Pharmacopeia. Drug Saf. 2008;31(6):469-484.

60 MEDSAFE New Zealand Government publication. Prescriber Update 2009;30(3):21.

61 Ulbricht C., Basch E., Boon H., et al. Safety review of kava (Piper methysticum) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:779-794.

62 Lude S., Torok M., Dieterle S., et al. Hepatocellular toxicity of kava leaf and root extracts. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:120-131.

63 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/cm/kavafs0504.htm

64 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi41.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

65 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi71.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

66 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi70.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

67 Adverse reactions to complementary medicines. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bull. 2005;24(1):2.

68 Voiles K.M., Kelly W.N. Potential interactions between oral contraceptives and other medication and natural substances. US Pharmacist. 29(1), 2004.

69 Clauson K.A., Santamarina M.L., Rutledge J.C. Clinically relevant safety issues associated with St John’s wort product labels. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008 Jul 17;8:42.

70 http://fedcache.funnelback.com/search/cache.cgi?collection=fedgov&doc=http%2Fwww.tga.gov.au%2Fdocs%2Fhtml%2Fcmec%2Fcmecdr50.htm

71 Agbabiaka T.B., Pittler M.H., Wider B., Ernst E. Serenoa repens (saw palmetto). A systematic review of adverse events. Drug Safety. 2009;32(8):637-647.

72 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/html/cmec/cmecdr04.htm (accessed 5 Oct 2009)

73 Shalansky S., Lynd L., Richardson K., et al. Risk of warfarin-related bleeding events and supratherapeutic International Normalised Ratios associated with complementary and alternative medicine: a longitudinal analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1237-1257.

74 Skin reaction with glucosamine. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. 2005;24(6):23.

75 Interaction between glucosamine and warfarin. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bull. 2008;27(1):3.

76 Yue Q.-Y., Stradell J., Myrberg O. Concomitant use of glucosamine potentiates the effect of warfarin. Drug Safety. 2006;29:911.

77 MHRA/CSM. Glucosamine adverse reactions and interactions. Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance. 2006;31:8.

78 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/legis/2008_rasml.htm (accessed 5 Oct 2009)

79 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/cmec/cmecmi60.pdf (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

80 Therapeutic Goods Administration and Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Adverse drug reactions: what to report. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/adr/report.htm (accessed 5 Oct 2009).

81 Health Canada. Online. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/report-declaration/guide/guide-ldir_indust_e.html#a2 9 (accessed 5 Oct 2009).