Advancement Flaps

Introduction

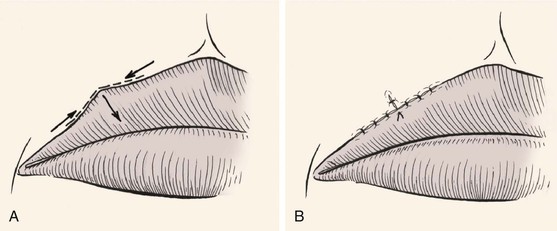

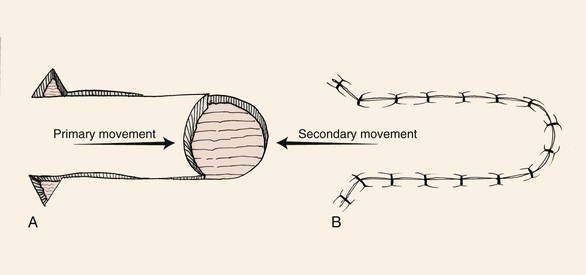

Most local cutaneous flaps used in the head and neck have some component of advancement during movement of the flap to the recipient site. An example is the paramedian interpolated forehead flap. Although this flap is classified as pivotal, it frequently is necessary to undermine the pedicle in the brow area to gain additional mobility and length to the flap. Thus the pedicle is advanced inferiorly below the bony orbital rim, adding some advancement to the main pivotal movement of the flap. The rhombic flap is another example in which both pivotal and advancement movements are important in transferring the flap to the recipient site. Most rotation flaps are also facilitated by advancement of their pivotal point. True advancement flaps have a linear configuration and are moved by sliding toward the defect. This involves stretching the skin of the flap. Thus, advancement flaps work best in areas of greater skin elasticity. The most basic advancement flap is the simple linear layered closure, which involves undermining and direct advancement of tissue side to side to close the defect primarily. This closure does not create a secondary defect, and additional incisions are made only for the removal of standing cutaneous deformities. However, the term advancement flap usually refers to a flap created by incisions that allow a “sliding” movement of the tissue. Tissue transfer is achieved by moving the flap and its pedicle in a single vector. The greatest wound closure tension is perpendicular to the distal border of the flap. Advancement flaps may be categorized as unipedicle, bipedicle, V-Y, Y-V, and subcutaneous tissue pedicled island flap (Table 9-1). By necessity, all advancement flaps must be designed so that the advancing border of the flap also represents a margin of the cutaneous defect that the flap is designed to repair. When an advancement flap is transferred to a defect, the motion of the flap is considered the primary tissue movement of the repair. Secondary tissue movement is the displacement of skin surrounding the defect toward the center of the primary defect (Fig. 9-1). Secondary movement always assists in wound closure by reducing wound closure tension. However, at times, secondary tissue movement may be detrimental if the defect is located near a mobile margin of a facial structure. Facial structures that are likely to be distorted if secondary tissue movement is excessive include the vermilion, nostril margin, lower and upper eyelids, and eyebrows. The stronger the attachments of facial structures to the underlying bone, the less propensity for distortion or displacement of these structures from secondary tissue movement. Complete undermining of advancement flaps as well as of the skin and soft tissue around the flap is likely to reduce wound closure tension and thus limit secondary tissue movement. If secondary movement could be beneficial in reducing wound closure tension and does not cause excessive distortion of facial landmarks, then wide undermining of the skin and mobilization of the tissue surrounding the defect are also indicated. At times it is preferable to allow movement only of the flap, in which case there should be limited or no undermining of the margins of the defect.

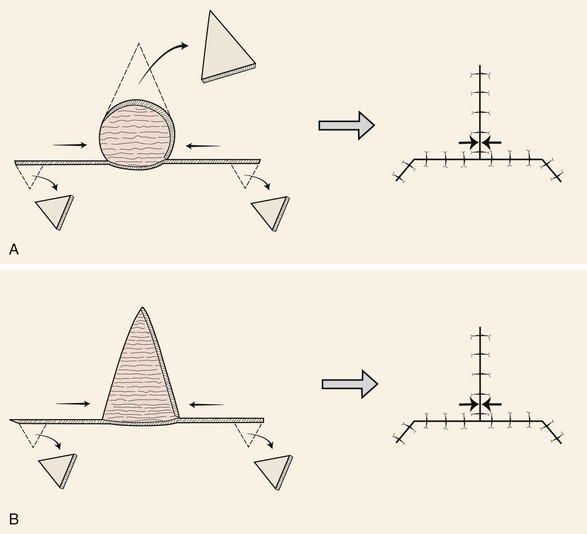

FIGURE 9-1 Unipedicle advancement flap. Primary and secondary skin movement occurs with wound repair.

All local flaps have inherent advantages and disadvantages, and these are often related to the flap design and the location where the flap is used. Certain cutaneous flaps work best in certain anatomic locations (see discussion of preferred flaps in Chapter 6). Advancement flaps are used for reconstruction of many surgical defects of the face. In considering the use of an advancement flap, it is important to consider the location of the vectors of wound closure tension and the location of incision lines and whether they respect relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) and aesthetic boundaries. The location where standing cutaneous deformities are likely to form and how they will be managed should be considered.1 Table 9-2 lists common locations on the face where advancement flaps are effective in repairing skin defects. As with all local flaps, it is important to evaluate the adjacent skin for matching qualities of texture, color, consistency, and hair growth.

Unipedicle Advancement Flaps

As the name implies, unipedicle advancement flaps have a single cutaneous pedicle. The flap is created by parallel incisions that allow a sliding movement of tissue in a single vector toward a defect. The movement is in one direction and flap advancement is directly over the defect. This form of wound repair is sometimes referred to as U-plasty. Complete undermining of the advancement flap as well as of the skin and soft tissue around the pedicle is important to enhance tissue movement. In contrast to pivotal flaps, which form a single standing cutaneous deformity, two deformities are created with all unipedicle advancement flaps. Unlike with pivotal flaps, in which the standing cutaneous deformity must be dealt with at the base of the flap, the deformities that develop from advancement can be excised anywhere along the length of the flap and not necessarily juxtaposed to the base. This is because of the mechanism of tissue movement.

Unipedicle advancement flaps and rotation flaps have one characteristic that is inherent only in these two flap designs. Owing to their specific design, the use of either type of flap creates a situation in which there exists an unequal length of the borders of the wound once the flaps are transferred to their respective recipient sites. This is because the peripheral border of the wound (flap incision plus defect width) is longer than the length of the flap. Triangular skin excisions along the periphery of the wound (equalizing or Burow triangles) in essence have the effect of shortening the peripheral border of the wound so that its length matches the length of the flap (see discussion in Chapter 7). In the case of rotation flaps, a single Burow triangle excision is required, whereas unipedicle advancement flaps require two excisions, one on either side of the flap. Excision of standing cutaneous deformities of advancement flaps is predicated on the most optimal site for excision. Typical excisions are placed in RSTLs or borders between aesthetic regions of the face. Sometimes the discrepancies in the length of the borders of the wound may be eliminated by a halving suture technique. The technique involves dividing in half the length of the wound repair with each consecutive suture. This evenly distributes the redundant tissue of the standing cutaneous deformities as small puckers along the entire length of the wound. Thus the redundancy is “sewn out” without the need for excision of skin.

Unipedicle advancement flaps are useful for repair of defects on the forehead. The flap is designed so that incisions are placed in or parallel to horizontal creases and, when possible, along the border of the eyebrow or anterior hairline. The unipedicle advancement flap should be conceptualized as rectangular in shape. Most cutaneous defects are round or oval, and a rectangular flap does not always precisely conform to a round defect. It may be necessary to modify the shape of the distal flap or the defect itself to minimize tissue distortion. It is usually preferable to “square off” the defect than to “round off” the flap. This is because angular incisions produce straight scars that have fewer propensities to develop trap-door deformities compared with curvilinear scars. Regardless of which option is selected, it is helpful to delay this modification until the flap has been elevated and has demonstrated its ability to cover the defect completely. Unipedicle advancement flaps are usually designed with parallel incisions extending from one border of the defect. However, these incisions are sometimes designed to diverge from each other when a greater width to the pedicle is desired or divergence can allow placement of incisions in facial aesthetic borders. Typically, unipedicle advancement flaps are designed with a ratio of defect width to flap length of 1 : 3.1,2 Therefore, large defects are more easily repaired with bilateral opposing flaps.

Bilateral Unipedicle Advancement Flaps

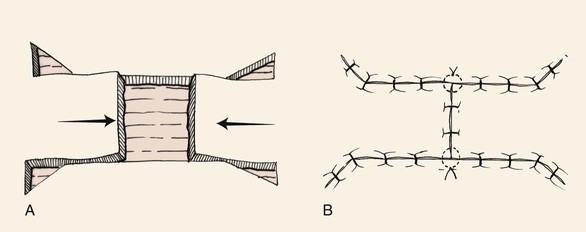

Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps are commonly combined to close various defects, resulting in H- or T-shaped repairs, depending on the configuration of the defect and the number of incisions used. Repair in this manner is often referred to as H-plasty (Fig. 9-2) or T-plasty. In both cases, advancement flaps are incised on opposite sides of the defect and advance toward each other. Each flap is responsible for covering a portion of the defect. When standing cutaneous deformities require excision, they are excised either in the area of the defect or along the borders of the flaps. The two flaps do not necessarily have to be of the same length. Flap length is determined primarily by the elasticity and redundancy of tissue at the donor site. The basic principles of tissue movement and wound closure are identical to those for single unipedicle advancement flaps. When designing and dissecting the flaps, it is wise to first incise and elevate only one flap. On occasion, sufficient skin movement is achieved with a single flap so that the second flap is not necessary or can be designed with less length. Like single unipedicle advancement flaps, bilateral flaps are useful for repairing skin defects of the forehead, eyebrow, and ear. Bilateral advancement flaps are particularly helpful for repair of defects of the central lips and chin. The advantage of bilateral flaps over a single flap for repair of these midline structures is that equal “pull” from the two opposing flaps lessens tissue distortion and the propensity toward deviation of midline structures toward one side. Similar to single advancement flaps, bilateral flaps will create wounds of unequal length often requiring removal of Burow triangles. These triangles may vary in size and location, depending on the location of the flaps and the elasticity of the tissues (Fig. 9-3).2 For instance, Figure 9-3 shows Burow triangles removed at different locations above and below the two flaps. In theory, these locations correspond to areas that result in the best scar camouflage. Figure 9-3B shows half-buried mattress sutures placed at the site of the Burow triangle excisions. Inferiorly, a four-point corner stitch is used.

T-Plasty

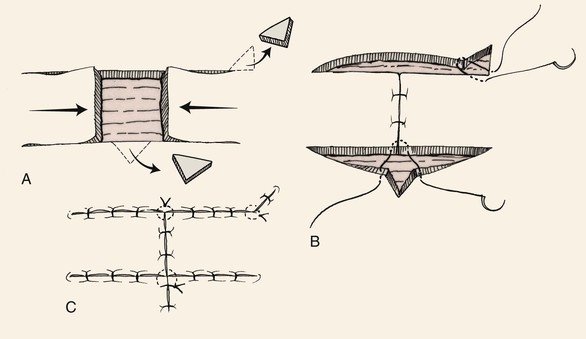

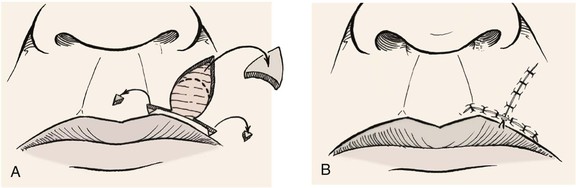

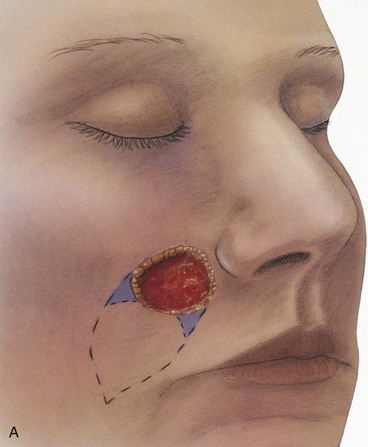

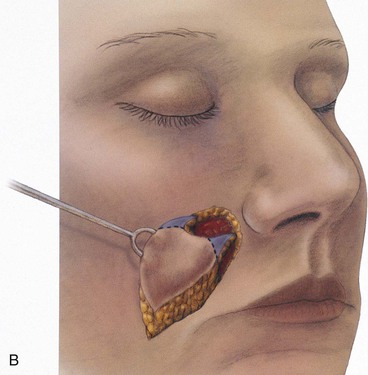

The A-T and O-T wound repair are so named because these methods transform a triangular (A-shaped) or round (O-shaped) defect into a T-shaped scar (Fig. 9-4). The T-plasty involves two flaps that are advanced in opposite directions toward each other. The standing cutaneous deformity that occurs to some degree with all advancement flaps is excised as the vertical limb of the T. If the horizontal limbs of the T-plasty are curved, flap movement is not solely advancement but a combination of rotation (pivotal movement) and advancement. T-plasty represents a modification of bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps. Instead of making two parallel incisions to create the flap, only one incision on opposing sides of the defect is made. The two flaps are advanced and slightly pivoted toward each other to repair the defect. A standing cutaneous deformity develops at the defect site opposite the position of the two incisions. This deformity is excised and the wound repaired, giving the final suture line a T configuration. The vertical limb of the T represents the excision of the standing cutaneous deformity. In addition, depending on the length of the incisions necessary to create the advancement flaps, standing cutaneous deformities may also form and require excision somewhere along the incision lines. An advantage of T-plasty repair is that the technique divides the defect in half by using two flaps for closure. Thus two smaller flaps can be used for repair instead of a single larger flap, which may be more difficult to harvest in areas where skin redundancy is limited. Another advantage of T-plasty is that only one incision is required to create each flap; thus fewer scars are created by not making parallel incisions to create the flaps as required for standard bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps. The horizontal limbs of the T-plasty can usually be positioned in natural creases or at junctions of aesthetic regions. T-plasty works very well for defects of the central forehead, where the vertical limb can be placed in the midline. The technique may also be used just above the eyebrow or on the temple adjacent to the hairline. In such cases, the horizontal component of the T is positioned along the lateral eyebrow or the anterior hairline. T-plasty is also an effective method of repairing cutaneous defects of the lateral lip adjacent to the vermilion (Fig. 9-5), the chin, and the preauricular and postauricular areas.3 When T-plasty is used to repair skin defects of the lips, excision of standing cutaneous deformities of the vermilion are not always necessary or can be made very small. In contrast, if primary repair is attempted, an excision of a large standing cutaneous deformity of redundant vermilion is required. T-plasty repair often eliminates this requirement and maintains the majority of incision lines on the cutaneous portion of the lip. Bilateral incisions are made along the vermilion margin at the base of the defect, thus creating two horizontal limbs of the T-plasty. The border of the defect opposite the vermilion is excised in a fusiform manner to remove a triangle of tissue. This triangle represents the standing cutaneous deformity that will form from advancement of the two flaps. The excision converts a round defect into a triangular defect (Fig. 9-5A). Wide undermining of adjacent skin is important to lessen wound closure tension, which in turn minimizes the risk of distortion of the philtrum. A four-point suture is placed in the midline of the base of the defect to precisely align the wound margins (Fig. 9-5B). When necessary, Burow triangles are removed along the border of the two flaps only after they have been advanced and secured. Schematically, small Burow triangles are removed at the most medial and lateral aspects of the horizontal limbs of the flaps (Fig. 9-5A). At times, because of the elasticity of lip skin, such triangles do not require excision. Instead, the triangles are sewn out by the principle of using halving sutures.3

FIGURE 9-4 A, O-T (T-plasty) repair of circular (O-shaped) wound. T-plasty requires two flaps advanced in opposite directions toward each other. The standing cutaneous deformity forming superiorly from advancement is excised at vertical limb of T. B, A-T (T-plasty) repair of triangular (A-shaped) wound. Wound closure suture line has T-shaped configuration. Opposing arrows indicate point of greatest wound closure tension.

FIGURE 9-5 A, O-T (T-plasty) repair of circular defect of upper lip near vermilion-cutaneous border. B, T-shaped wound closure avoiding incisions into vermilion.

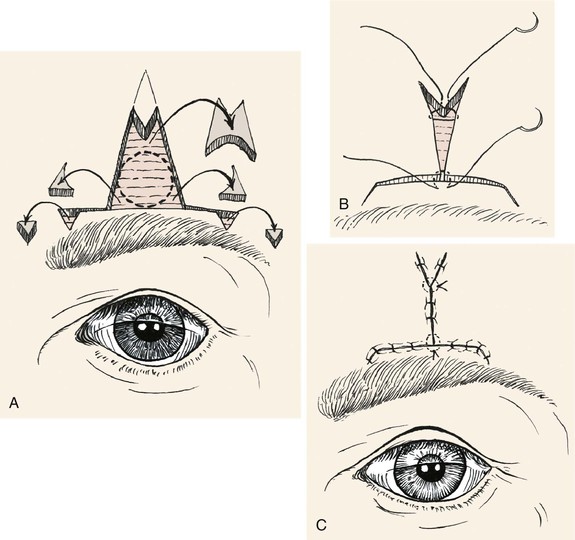

Figure 9-6A shows a typical round surgical defect above the left eyebrow, an area where the T-plasty repair works well. First, it is helpful to mentally superimpose a triangle over the circular defect. In reality, the circle is converted to a triangle by removal of wedges of tissue at the perimeter of the circle at three points equally separated from each other. In Figure 9-6A, note that the superior wedge is in the form of an M-plasty, which helps to minimize the length of the vertical limb of the scar. Two horizontal incisions are made perpendicular to the vertical limb to create advancement flaps. These incisions may be varied in length and may curve, allowing proper placement in RSTLs, such as the horizontal crease lines of the forehead. The flaps are then elevated and advanced into the primary defect, with the key suture being placed at the central advancing borders of the two flaps. Undermining should be sufficient to allow minimal wound closure tension. It is preferred not to excise the Burow triangles until complete undermining is accomplished and the flaps are advanced into the primary defect. Burow triangles are usually removed near the base of the flaps but, in actuality, can be removed from any area along the incision line if it hides well in RSTLs. A four-point suture is used to approximate the opposing distal tips of the two flaps and adjacent skin (Fig. 9-6B). The tip of the M-plasty is closed with a similar half-buried horizontal mattress tip suture. Repair is completed by suturing the flaps together by layered closure (Fig. 9-6C).

FIGURE 9-6 A, O-T (T-plasty) repair of circular skin defect near eyebrow. Wedges of skin removed from perimeter of circle. Superiorly, M-plasty limits vertical scar length. The Burow triangles are removed at end of horizontal limb of flaps. B, Half-buried horizontal mattress tip sutures. C, Wound closure with M-plasty avoids distortion of eyebrow.

Modified T-Plasty

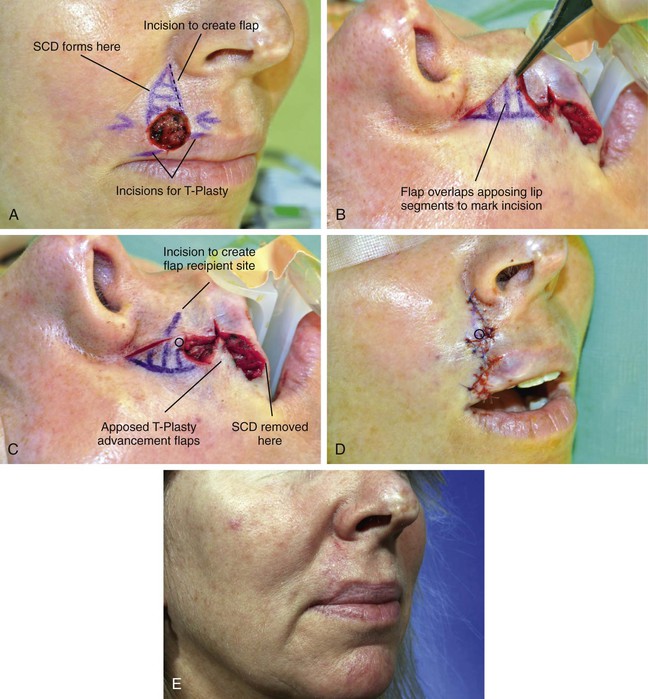

The greatest problem with T-plasty repair of large (2 cm or greater) circular cutaneous defects of the lip is ectropion of the vermilion as the wound heals. This is due to the contracture of the vertical portion of the T-shaped scar. In addition, T-plasty flaps are not pure advancement flaps. Some pivotal movement occurs, and this causes a small reduction in effective flap length. This in turn causes shortening of the vertical wound closure line. To avoid vermilion ectropion, a modified T-plasty can be performed. Instead of excision of the standing cutaneous deformity that develops opposite the incision lines for the two opposing flaps, the tissue of the deformity is preserved and used to lengthen the vertical component of the T-plasty scar (Fig. 9-7). The two opposing borders of the flaps are first approximated at the vermilion line. The resulting standing cutaneous deformity that forms opposite the flap incisions is marked. Only half of the typical incision to excise the deformity is made. This creates a flap of skin that is pivoted and advanced into a second horizontally oriented incision made in the opposing lip segment. The orientation and length of the second incision are designed after the first incision creating the flap of skin has been performed. The flap is positioned over the adjacent lip segment, and the distal end of the overlapping flap is marked on the lip segment. A line is drawn from this point to the lip segment wound border. The line is angled so it is centered beneath the linear axis of the overlapping flap. An incision is then made along this line. The borders of the incision are undermined. The flap is then sutured into the recipient site created by the second incision. On occasion, a small portion of the flap must be trimmed to allow it to fit perfectly within the opposing lip segment. This technique in essence is a modified Z-plasty, which has the effect of lengthening the otherwise straight vertical component of the T-plasty scar. The vertical scar resulting from the modified T-plasty has an irregular Z-shaped configuration (Fig. 9-8).

FIGURE 9-7 A, Modified O-T (T-plasty) repair of circular cutaneous defect of upper lip. Inferior broken lines indicate incisions to create advancement flaps as part of classic T-plasty repair. Superior broken lines indicate incisions to create transposition flaps for modified Z-plasty, which eliminates need to excise standing cutaneous deformity superiorly. B, Flaps incised and dissected, small standing cutaneous deformities excised from vermilion border if necessary. C, Wound repaired. Vertical component of scar has Z configuration.

FIGURE 9-8 A, A 1.5 × 1.2-cm circular cutaneous defect. Modified T-plasty designed for wound repair. Broken line indicates planned incision along border of anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (SCD). B, Flap created by incision marked by broken line in A overlaps medial lip segment to mark incision for recipient site. C, Incision marked to create recipient site for flap. Distal tip of flap marked with circle. D, Flap transposed to create modified Z-plasty vertical wound repair. Circle marks distal end of flap. E, Postoperative view at 2 months.

V-Y and Y-V Advancement Flaps

Like the T-plasty, V-Y and Y-V advancement flaps do not require two parallel incisions to create the flap (see discussion of these flaps in Chapter 6). The V-Y advancement flap is unique in that the V-shaped flap is not stretched or pulled toward the recipient site but rather achieves its advancement by recoil or by being pushed forward. Thus the flap is allowed to move into the recipient site in a nearly tension-free fashion. The secondary triangular donor defect is then repaired with wound closure tension by advancing the two borders of the remaining wound toward each other. In so doing, the wound closure suture line assumes a Y configuration, with the common limb of the Y representing the suture line resulting from closure of the secondary defect. The flap is optimally designed so that the common limb of the Y falls in the boundary of neighboring aesthetic regions or within a natural crease, fold, or wrinkle.

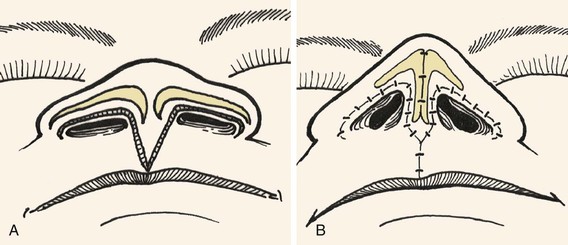

V-Y advancement is useful in situations in which a structure or region requires lengthening or release from a contracted state. The technique is particularly effective in lengthening the columella during the repair of cleft lip nasal deformities in which a portion or all of the columella is underdeveloped. A V-Y advancement flap is elevated recruiting skin from the midportion of the lip between the philtral ridges. The length of the columella is augmented by advancement of the flap upward into the base of the columella (Fig. 9-9). The secondary donor defect is approximated by advancement of the remaining lip skin together in the midline. V-Y advancement is helpful in releasing contracted scars that are distorting adjacent structures, such as the eyelid or vermilion. An example is the correction of an ectropion of the vermilion caused by scarring. The segment of distorted vermilion is incorporated into the V-shaped flap and the flap is advanced toward the lip to restore the natural topography of the vermilion-cutaneous junction. The secondary defect is closed by advancement. The suture line resulting from closure of the secondary defect becomes the vertical component of the Y configuration (Fig. 9-10).

FIGURE 9-9 A, B, V-Y advancement flap dissected from philtrum by recruiting skin from midportion of lip between philtral ridges. Length of columella augmented by advancement of flap superiorly into base of columella.

Bipedicle Advancement Flaps

Bipedicle advancement flaps are used primarily for repair of large defects of the scalp. The flap is designed adjacent to the defect and is advanced into the defect at a right angle to the linear axis of the flap. This leaves a secondary defect that usually must be repaired with a split-thickness skin graft. As a consequence, bipedicle flaps are rarely used for reconstruction of the face and neck. The exception to this is bipedicle nasal vestibular skin advancement flaps used for lining full-thickness nasal defects of the hemi-tip or ala that have a vertical height of no more than 1.0 cm (see discussion of this flap in Chapter 18). The flap consists of vestibular skin and mucosa based medially on the septum and laterally on the floor of the nasal vestibule. An extended intercartilaginous incision is made and the flap is elevated off the undersurface of the alar cartilage and mobilized inferiorly to line the ala or hemi-tip. The donor site on the ventral aspect of the cartilage is covered with a thin full-thickness skin graft. The bipedicle flap is thin and provides natural physiologic material for the interior of the nasal passage with sufficient vascularity to support the concomitant use of free cartilage grafts placed over the lining flap for structural support of the construction.

Applications

Forehead

A general discussion of surgical techniques and preoperative and postoperative surgical care of patients undergoing local flap reconstruction is provided in detail in Chapters 4 and 5. The most effective technique for reconstruction of forehead cutaneous defects usually involves one or more advancement flaps. In spite of the relative inelasticity of forehead skin, the use of advancement flaps versus pivotal flaps is preferred because they typically produce the best aesthetic results. This is because incisions necessary for advancement flaps may be placed in the horizontal creases of the forehead or along the border of the eyebrow, depending on the location of the defect. Transposition flaps work well in the region of the temple, but more medially on the forehead it becomes difficult to close the donor site when such flaps are used.

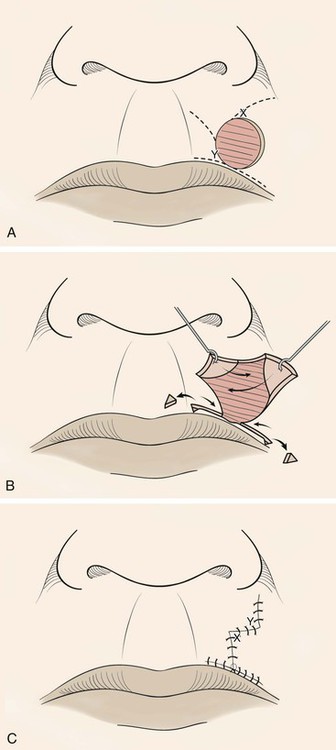

Cheek

Cheek defects are commonly repaired with advancement flaps and take to their advantage the relative mobility and elasticity of the skin and soft tissue of the cheek.4,5 A common site for the development of skin cancers is the junction between the nose and cheek along the nasofacial sulcus. Defects resulting from removal of cancers in this area that cannot be closed primarily are usually best repaired by moving cheek skin medially to the aesthetic border between the nasal sidewall and the cheek. This usually is accomplished by using a laterally based unipedicle advancement flap (Fig. 9-11). Medium to large defects (2-4 cm) in this area can be closed by medial advancement of cheek skin. Standing cutaneous deformities are excised superiorly at the junction line between the cheek and the nasal sidewall and inferiorly in the melolabial crease (Fig. 9-11B). For smaller defects of the medial cheek (2 cm or less) near the nasal sidewall, incisions to create an advancement flap may not be necessary. The defect can frequently be closed primarily through advancement of the wound margins with excisions of standing cutaneous deformities along the nasofacial and alar-facial sulcus.

FIGURE 9-11 A, Advancement flap used to repair skin defect of medial cheek. Superior incision made at infraorbital crease between eyelid and cheek skin. Inferior incision made in nasofacial sulcus extending, if necessary, into melolabial crease. Broken line represents extent of skin undermining. B, Suspension suture used to attach dermis of flap to periosteum of maxilla. Excision of Burow triangles performed at base of flap. C, Wound closure suture line within aesthetic borders between cheek, lip, nose, and eyelid.

For defects of the medial cheek, it is important to maintain the integrity and contour of the nasofacial sulcus, which is the valley between the nasal sidewall and cheek. If cheek advancement flaps are advanced into the nasal sidewall, they often blunt the concavity of the nasofacial sulcus. Other times such techniques may tent up tissue in the sulcus, causing the appearance of a bridge or web of tissue across the concavity of the sulcus. Therefore, defects of the medial cheek that also involve the nasal sidewall should be repaired with separate flaps or grafts, one for the sidewall and one for the cheek component of the defect. Even when defects located in the nasofacial sulcus do not extend to the nasal sidewall, cheek advancement flaps used to repair the defect may cause some blunting of the sulcus. This undesirable effect can be minimized by the use of a periosteal tacking suture made of absorbable polyglactin or polydioxanone (Fig. 9-11B).6 Such sutures are placed in the dermis of the advancing flap several millimeters behind the advancing border of the flap and are sutured deeply to the periosteum of the underlying bone. This technique helps relieve wound closure tension on the suture line along the distal border of the flap and concomitantly helps maintain the nasofacial sulcus by minimizing dead space beneath the flap. Standing cutaneous deformities form at the base of the flap’s pedicle and can be easily removed by extension of the incisions along the same aesthetic borders as shown in Figure 9-11B. The excised skin, of sufficient size, provides an excellent source for grafting of any defect of the sidewall of the nose.

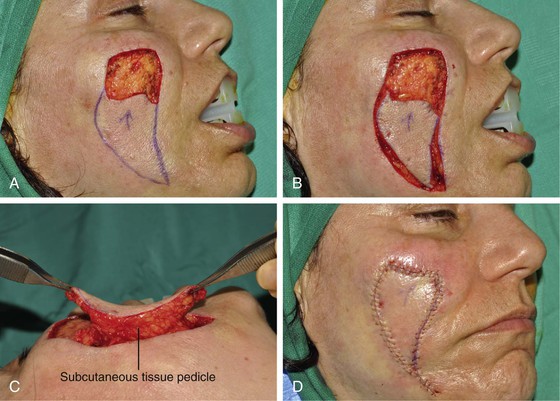

The perimeter of the skin island is incised to the level of the subcutaneous tissue. Undermining of the adjacent facial skin peripheral to the flap for a distance of 2 cm is performed at this level. Blunt and sharp dissection is then carried through the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the skin island, beveling slightly away from the skin island down to the level of the fascia overlying the facial musculature. This frees the elastic subcutaneous tissue pedicle from its medial and lateral fatty attachments to surrounding cheek fat while preserving its vascular supply, which is derived from its deep attachments. The skin island is then advanced toward the defect by placing a skin hook at its leading border (Fig. 9-12). At this point, the pedicle can be narrowed to facilitate the advancement of the flap. This is accomplished by back cutting the peripheral borders of the flap in a subcutaneous plane, leaving at least one-third of the total flap surface area attached to the underlying subcutaneous tissue. Further thinning of the subcutaneous tissue underlying the undermined portion of the flap may be performed to create an appropriate thickness match between the leading border of the flap and the recipient site. A central pedicle of one-third of the total skin island surface area will adequately perfuse the skin island. Further subcutaneous undermining of the skin adjacent to the flap is required if puckering of the peripheral facial skin occurs with flap mobilization. Subcutaneous undermining is also performed at the recipient site. In addition, the recipient site’s depth and shape may be modified by removing skin and subcutaneous tissue so that scars will be along aesthetic boundary lines and the defect will more appropriately accommodate the thickness of the advancement flap. The leading border of the skin island is fixed in place, and the wound surrounding the remaining perimeter is subsequently closed such that wound closure tension is equally distributed over the entire length of the flap. The donor site is closed in a V-Y fashion, with care taken to compensate for any differences in the length of the opposing margins of the donor site.

FIGURE 9-12 A, Circular skin defect of medial cheek converted to angular defect by removal of small triangles of tissue at perimeter of defect. Triangular island flap marked by broken line. B, Flap advanced on subcutaneous tissue pedicle. C, Secondary defect closed in V-Y configuration.

For sizeable (2-3 cm) skin defects located adjacent to the inferior border of the ala, it may be beneficial to excise the small peninsula of skin between the ala and melolabial fold in the process of enlarging the defect so that it extends to an aesthetic boundary (see Fig. 9-12).7 This peninsula is then reconstructed by appropriately designing the island flap so that the superior portion of the flap replaces the peninsula. This technique provides the best scar camouflage because the superior border of the flap is positioned within the aesthetic boundary of the alar-facial sulcus. When this peninsula is not replaced, the flap must cross the base of the peninsula and may mar an otherwise excellent result.

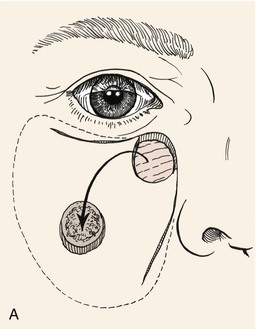

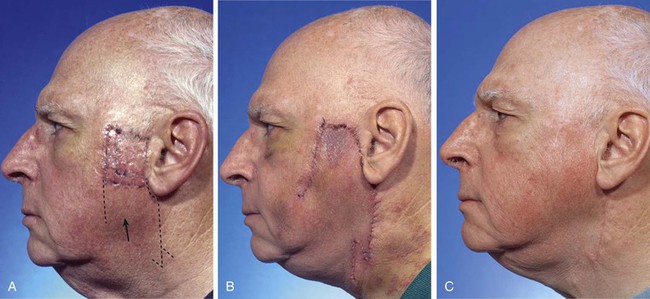

Lateral cheek skin has less subcutaneous cheek fat and is more adherent than medial cheek skin to the underlying fascia. For this reason, V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flaps work less well here because such flaps depend on ample subcutaneous tissue for movement. Although smaller defects of the lateral cheek are best repaired with transposition flaps, large defects (greater than 3-4 cm) are most easily reconstructed with rotation advancement flaps. From the lateral inferior border of the defect, a curvilinear incision extends downward and posteriorly below the earlobe and then backward to the posterior hairline. From there, the incision extends inferiorly along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Flaps are based medially and inferiorly and can provide a flexible means of transferring large areas of skin from the remaining cheek and upper cervical regions. Patients who use tobacco products or have been irradiated in the area of the defect may benefit from inclusion of the platysmal muscle in the advancement flap used to repair large lateral cheek defects (see discussion in Chapters 6 and 7). The deeper plane of dissection ensures a greater blood supply to the flap than if dissection is in the subcutaneous plane.

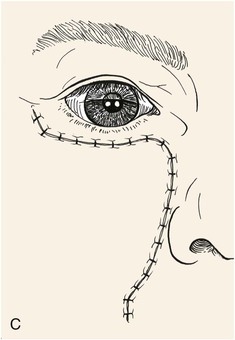

Eyelid

When a defect of the anterior lamella of the lower eyelid is encountered, a horizontal subcilial incision is made along the length of the eyelid approximately 2 mm beneath the lash line.8 An advancement flap consisting of the entire lateral lower eyelid skin and muscle is developed. To avoid any distortion of the eyelid or fat pads, it is important that the musculocutaneous flap be dissected completely free of any adherence to the underlying orbital septum. It may be necessary to carry this incision past the lateral canthus to recruit adjacent skin from the temple and lateral cheek. If necessary, an inferior incision along the nasofacial sulcus can also be used to free up additional tissue for the superior movement of cheek skin.

Lip

V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flaps are ideally suited for repair of lateral skin defects of the upper lip. They do not work as well for defects of the lower lip. As discussed earlier, this flap design is also ideal for medial cheek defects adjacent to the nasal alae. The flap is dissected in a fashion similar to the method discussed for its use in repair of medial cheek defects except the flap is freed from its orbicularis muscle attachments near the commissure and is based solely on the abundant subcutaneous fat located just lateral to the commissure. The flap is designed as an isosceles triangle, the base of which abuts the defect to be repaired.9 The two approximately equal sides of the triangle are designed to meet in the melolabial crease inferiorly and laterally. The base of the triangle is the height of the defect, and the height of the triangle is two times the width of the defect. The incisions to create the flap are made to the level of the orbicularis oris. If the width of the flap does not extend to the cheek fat lateral to the orbicularis oris, the muscle is left attached to the majority of the underside of the flap. Only peripheral margins of the flap are undermined to allow eversion of the wound edges. It may be necessary to incise through some of the muscle to increase mobility. When the flap is sufficiently wide to incorporate the abundant fat lateral to the orbicularis oris, the flap may be partially or completely released from the orbicularis oris for greater mobility. After the flap is advanced into the recipient site, the secondary defect is closed by advancement in a horizontal vector. A vertical vector of closure should be avoided to prevent upward distortion of the vermilion.9 When it is properly designed, the flap provides the best skin color and texture match with lip skin because the flap is composed solely or predominantly of skin of the lip. The flap donor site scar parallels or lies in the melolabial crease, an important aesthetic border. All scars are confined to the aesthetic regions of the lips. In men, the flap contains hair-bearing skin with the same downward orientation of hair growth as in the remaining upper lip.9

Case Reports

Case 1

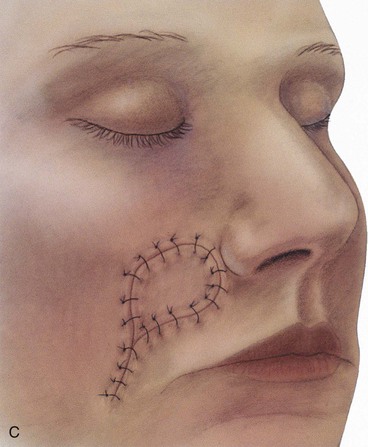

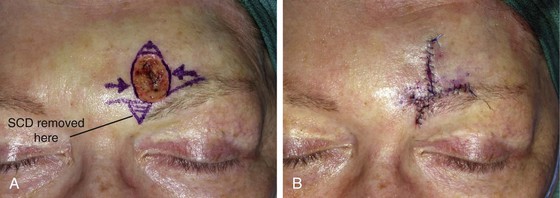

A 57-year-old woman was evaluated for excision of a 4 × 3-cm central forehead skin graft that was used to repair a cutaneous defect after micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 9-13). The options for local flap reconstruction of the defect resulting from skin graft excision included bilateral advancement flaps in the form of a large H-plasty and excision of the graft and underlying frontalis muscle with repair by primary wound closure. H-plasty would have required lengthy horizontal forehead incisions and dissection of advancement flaps in the subcutaneous tissue plane. Because long flaps would have been necessary, flap vascularity may have been compromised. For this reason, primary wound repair of large forehead skin defects is usually preferred. Primary wound closure requires advancement of the remaining forehead skin, which creates large standing cutaneous deformities superior and inferior to the skin defect. In this case, the skin graft and underlying muscle were excised and the forehead skin on either side of the defect resulting from excision was undermined in the subgaleal plane. This dissection plane preserved the supraorbital sensory nerves supplying the skin of the forehead and anterior scalp. An M-shaped excision (M-plasty) was used to remove the standing cutaneous deformity inferior to the defect resulting from the advancement of forehead skin. This method of excising the deformity eliminated the need for extension of incisions into the eyebrow and upper eyelid. The standing cutaneous deformity forming superior to the defect was excised in an ellipse. Complete closure of the wound was possible.

FIGURE 9-13 A, A 4 × 3-cm skin graft of central forehead. Excision and primary wound closure planned. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformities (SCD) resulting from advancement of wound margins after excision of skin graft are marked with horizontal lines using M-plasty inferiorly. B, Skin graft excised and wound repaired. C, D, Preoperative and 2-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

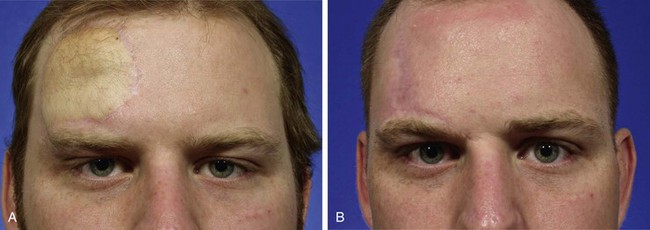

The patient shown in Figure 9-14 presented with a similar unsightly appearance of the forehead. The patient suffered a full-thickness avulsion of the soft tissue of the lateral forehead. The tissue defect was reconstructed with a microvascular radial forearm flap. Although the flap provided adequate cover for the exposed frontal bone, it was unsightly because of skin color and texture mismatch with adjacent native forehead skin. The flap measured 6.0 × 5.5-cm and was too large to be excised in one surgical stage and for complete wound closure to be expected. For this reason, serial excision of the flap concomitant with forehead skin advancement was planned.

FIGURE 9-14 A, A 6 × 5.5-cm radial forearm flap used to cover large full-thickness soft tissue defect. Vertical line indicates planned incision for serial excision (first stage) of flap. B, After first surgical stage. C, Planned second surgical stage serial excision. D, After second surgical stage. E, Planned third surgical stage serial excision. F, After third surgical stage. G, Planned fourth surgical stage serial excision and scar revision with direct eyebrow lift. H, After fourth surgical stage.

Serial excision required four surgical procedures to completely excise the flap. An interval of 6 to 7 months elapsed between partial excisions of the flap. Figure 9-14A-H shows the patient’s forehead before and immediately after each surgical stage. The standing cutaneous deformity forming at the superior border of the eyebrow as a result of advancement of the forehead and temple skin during wound closure after partial flap excisions were partially excised by an M-plasty excision as described in the preceding case. Not all of the standing cutaneous deformities developing near the eyebrow could be excised without resection of a portion of the eyebrow. As a result, the eyebrow was displaced inferiorly. This was corrected at the time of the last surgical stage by including a direct brow lift with the vertical scar revision that was performed. Figure 9-15 shows the preoperative and final appearance of the forehead after a total of four partial excisions of the flap.

FIGURE 9-15 A-D, Same patient shown in Figure 9-14. Preoperative and 6-month postoperative views after the fourth surgical stage.

This case clearly demonstrates the value of serial excisions followed by primary wound closure in removal of large congenital nevi, vascular malformations, or skin deformities of the forehead by use of this surgical approach. The case presented could have also been treated with controlled tissue expansion of the native forehead skin followed by excision of the flap and advancement of the expanded forehead skin laterally to repair the defect resulting from excision. This option was discussed with the patient. The patient declined in favor of serial excisions. Controlled tissue expansion is discussed in detail in Chapter 25.

Case 2

A 56-year-old woman was referred for treatment of a melanoma in situ of the forehead. Clear margins around the lesion had been established by members of the University of Michigan dermatology department by use of a system known as the square technique.10,11 The square technique is discussed in detail in the Case Reports section of Chapter 8. The patient in Figure 9-16 shows a melanoma in situ with the margins outlined by a running suture creating a square of the central forehead skin measuring 1.5 × 1.5-cm. The square of skin was excised and the wound repaired with bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps. The area of skin excised was small relative to the examples discussed in case 1. Therefore, it was elected to excise the lesion and to repair it with bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps. Each flap was dissected in the subcutaneous plane to preserve the cutaneous innervation of the forehead skin. The standing cutaneous deformities that formed along the superior borders of the flaps were excised together in a vertical line immediately above where the two flaps were opposed. Because of the elasticity of the lower portion of the forehead skin, the standing cutaneous deformities forming at the inferior borders of the flaps were eliminated by a halving suture technique. The H-plasty used in this patient places the majority of the incisions in RSTLs. This ensures that scars are camouflaged by lying in or parallel to the horizontal creases of the forehead.

FIGURE 9-16 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm square of forehead skin outlined by sutures. Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps (H-plasty) designed for repair of wound resulting from excision of square. B, Square excised and wound closed. Standing cutaneous deformity formed by tissue advancement removed superior to H-plasty. It was not necessary to remove standing cutaneous deformity inferior to H-plasty. C, Postoperative view at 4 months. No revision surgery performed.

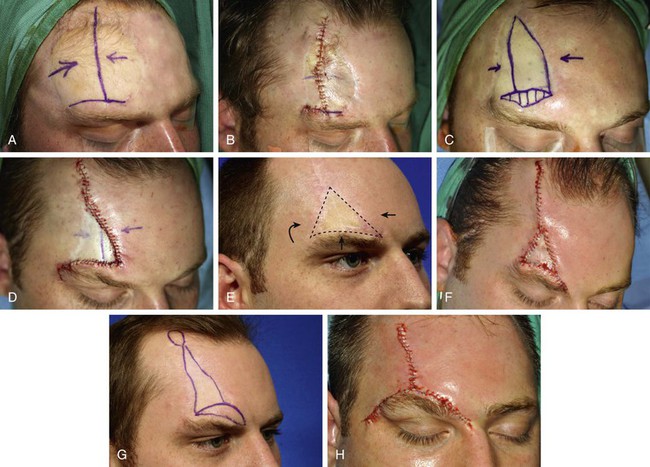

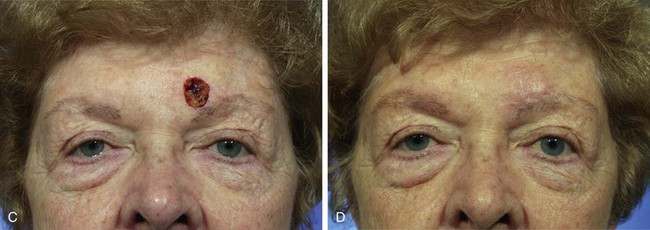

Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps work well for repair of small (2 cm or less) skin defects located anywhere on the forehead, like the one shown in Figure 9-16. H-plasty is particularly useful in repairing skin defects in or adjacent to the eyebrow. This is because the skin adjacent to the eyebrow is more elastic than skin elsewhere on the forehead and is more easily transferred as an advancement flap. In addition, the skin of the temple can frequently be recruited into a laterally based advancement flap to facilitate wound closure. An example of this is shown in Figure 9-17. This 54-year-old woman presented with a 3.5 × 2.5-cm skin defect of the eyebrow and forehead skin after micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma. Although the defect encompassed a large section of the eyebrow, a small portion of the eyebrow persisted laterally. This portion was incorporated into an H-plasty so that it could be advanced medially to establish eyebrow continuity. A Z-plasty was designed at the superior border of the lateral flap, and Burow triangle excisions were planned along the inferior borders at the bases of the two advancement flaps.

FIGURE 9-17 A, B, A 3.5 × 2.5-cm skin defect of forehead and eyebrow. Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps (H-plasty) designed for repair of wound. Lateral portion of eyebrow incorporated into lateral advancement flap. Burow triangles marked in crow’s-feet laterally and glabellar rhytid medially. Z-plasty marked at superior border of lateral flap. C, Flaps advanced. Marked advancement of lateral flap eliminated need to make entire planned incisions of medial flap. Planned Z-plasty not performed. D, Flaps approximated. Standing cutaneous deformities removed inferiorly from crow’s-feet and superiorly at base of lateral flap. E, Postoperative view at 4 months. No revision surgery performed.

The lateral-based flap was incised first and dissected in the subcutaneous plane. Because of the mobility of the flap, wound closure was possible without making planned incisions along the full length of the medially based flap. The lateral flap was advanced sufficiently to create a standing cutaneous deformity that could not have been eliminated with a Z-plasty. Therefore, Burow triangles were excised above and below the base of the flap. The degree of advancement of the lateral flap enabled a medial flap of diminutive length. As a result, it was not necessary to excise standing cutaneous deformities along the borders of this flap. The H-plasty shown in Figure 9-17 places most of the suture lines in RSTLs and along the border of the eyebrow, which is an important boundary between aesthetic facial regions. This case demonstrates the wisdom of first incising the flap that is designed in the area of greatest skin elasticity. On occasion, significant skin movement is achieved with a single flap so that the second flap is not necessary or, as in this case, can be created with less length than is anticipated.

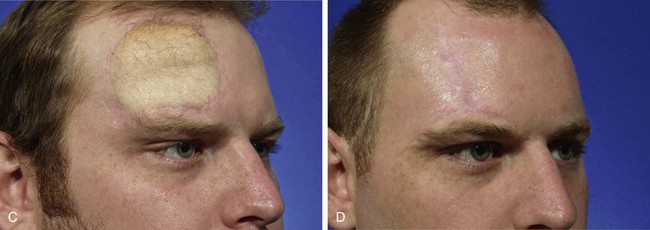

T-plasty is often effective in repairing small (2 cm or less) skin defects located above the eyebrow. The relatively lax skin immediately superior to the eyebrow can be used to develop bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps. An example of this is shown in Figure 9-18. The patient is an 81-year-old woman who had micrographic surgery for a basal cell carcinoma of the left central aspect of the forehead. The resulting skin defect measured 1.7 × 1.4-cm and was adjacent to the medial aspect of the eyebrow. The limb of the lateral flap of the T-plasty is drawn along the border of the eyebrow and the anticipated standing cutaneous deformities are marked with horizontal lines. The flaps of the T-plasty were dissected in the subcutaneous tissue plane. Wound closure was achieved with only minimal wound closure tension.

FIGURE 9-18 A, A 1.7 × 1.4-cm skin defect of left forehead. T-plasty designed with limb of laterally based flap positioned along border of eyebrow. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformities (SCD) marked by horizontal lines for excision. B, Wound closed. Standing cutaneous deformity removed. C, D, Preoperative and 6-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

Case 3

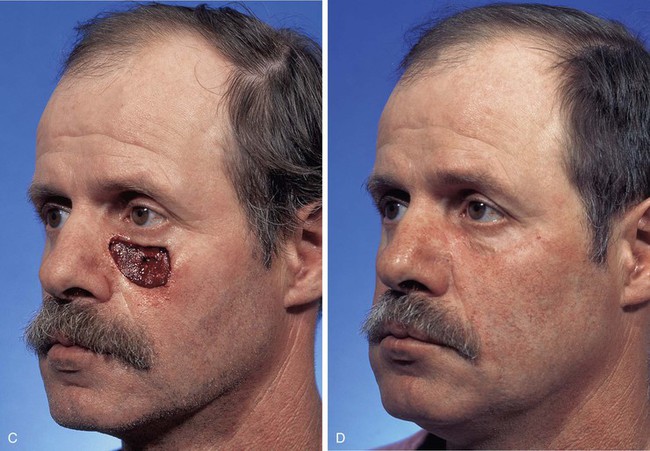

A 55-year-old woman developed a superficial spreading melanoma of the cheek. A 4 × 4-cm skin defect resulted from resection of the lesion (Fig. 9-19). The three most likely successful methods of repair for such a large defect are full-thickness skin graft, a skin flap of the cheek transferred as a transposition, and an advancement flap. For cutaneous defects located near the lower eyelid, a unipedicle advancement flap is usually preferred for repair. Such a flap was designed in this case with bilateral Z-plasties at the base of the flap to facilitate tissue movement and to reduce the standing cutaneous deformities resulting from advancement. The flap was elevated in the subcutaneous plane and advanced superiorly and medially. The lengthy advancement of the flap necessitated the excision of a small standing cutaneous deformity anteriorly along the inferior mandibular margin.

FIGURE 9-19 A, A 4 × 4-cm superficial melanoma marked for excision. B, Unipedicle advancement flap designed for repair of wound. Z-plasties marked at base of flap. C, Flap in place. D, E, Postoperative views at 1 year. No revision surgery performed. (From: Baker SR: Local Cutaneous Flaps. Otolaryngology Clin N. Am 27:1994, W.B. Saunders, p 147, Fig 5 B-E, with permission.)

Repair of skin defects of the superomedial cheek that are smaller than the one seen in Figure 9-19 do not always require making parallel incisions to create an advancement flap. For example, the defect shown in Figure 9-20 was repaired by a unipedicle advancement flap. Although the majority of the flap movement was in the form of advancement, some pivotal movement was also used to transfer the flap. The pivotal movement, although limited, eliminated the need to make two parallel incisions to create the flap. A single long incision was designed in the melolabial crease in addition to a Z-plasty to eliminate the standing cutaneous deformity forming at the anterior border of the flap. A sizeable standing cutaneous deformity was excised lateral to the skin defect as marked on the patient’s face. Wound closure resulted in lower eyelid retraction, so the wound was open between the border of the flap and the eyelid skin to release wound closure tension. The exposed area was repaired with a full-thickness skin graft that was obtained from the excised and discarded standing cutaneous deformity. Figure 9-21 shows the preoperative and postoperative views of the patient. The prudent use of a small full-thickness skin graft in combination with the advancement flap prevented postoperative lower eyelid retraction or ectropion. Chapter 16 discusses in detail the combined use of full-thickness skin grafts and local cutaneous flaps for repair of large facial defects.

FIGURE 9-20 A, A 3 × 1.5-cm skin defect of medial cheek. Unipedicle advancement flap with Z-plasty at base designed for repair of wound. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity marked by vertical lines lateral to defect. B, Excessive wound closure tension caused lower eyelid retraction. This was relieved by placing small full-thickness skin graft between flap and eyelid skin.

FIGURE 9-21 A-D, Same patient shown in Figure 9-20. Preoperative and 5-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

Unipedicle advancement flaps work well for repair of skin defects of the medial cheek because of the elasticity of skin in this region of the face. However, unipedicle advancement flaps may also be used for repair of defects of the lateral cheek. An example of this is shown in Figure 9-22. The patient is a 70-year-old man with lentigo maligna of the left cheek. Clear margins around the lesion were established by the square technique described in the Case Reports section of Chapter 8. The area outlined by sutures shown in Figure 9-22A measured 4 × 4-cm and was resected in the subcutaneous tissue plane. The resulting skin defect was reconstructed with an inferiorly based unipedicle advancement flap. The posterior border of the flap was made longer than the anterior border and a Z-plasty was used at the base of the flap. Because of the marked redundancy of the upper cervical and lower facial skin, the flap was advanced with ease, resulting in repair without excessive wound closure tension.

FIGURE 9-22 A, A 4 × 4-cm square of skin outlined by sutures and intended for resection. Broken line indicates planned unipedicle advancement flap. B, Flap advanced after resection of square. Z-plasty performed at posterior border of flap base. C, Postoperative view at 11 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 4

A 52-year-old woman was referred for excision of a melanoma in situ of her right cheek. The square technique had been used to establish clear margins around the skin lesion (Fig. 9-23). The area marked with sutures and to be resected was rectangular and measured 3.5 × 4.0 cm. The alternative methods of repairing the cheek defect with a local cutaneous flap after excising the lesion included a flap transferred by advancement, transposition, or rotation. The advancement flap could have been in the form of a cutaneous pedicled or a subcutaneous tissue pedicled island flap. The latter design was selected for repair. Island advancement flaps are most effective in the area of the medial cheek. The abundant fat of the medial cheek facilitates the advancement of the island flap because the flap is based solely on the subcutaneous tissue beneath the skin.

FIGURE 9-23 A, A 3.5 × 4-cm skin defect of medial cheek after excision of melanoma in situ. V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle advancement flap designed for repair of wound. B, Flap incised and dissected. C, Flap attached to subcutaneous tissue pedicle. D, Flap in place. E-H, Preoperative and 2-year postoperative views.

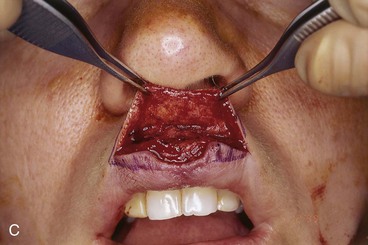

Case 5

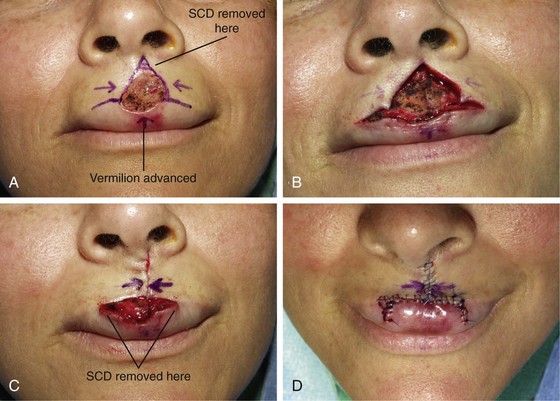

Advancement flaps used to repair cutaneous defects of the lips are usually oriented in such a manner that their advancement is in a horizontal plane. However, on occasion, advancement flaps are best designed with a vertical vector of advancement. An example of this is shown in Figure 9-24. Although this skin defect could have been repaired with an O-T closure, the resulting T-plasty would necessitate excision of a standing cutaneous deformity within the philtrum. This in turn would have narrowed the philtrum. For this reason it was elected to repair the skin defect in a horizontal orientation by use of superiorly and inferiorly based unipedicle advancement flaps. The superior flap was created by making an incision on either side of the defect along the vermilion-cutaneous border and dissecting a superiorly based cutaneous flap (Fig. 9-24C). The inferior flap was created by the same incisions and dissecting an advancement flap consisting of vermilion and mucosa (Fig. 9-24D). The two flaps were advanced toward each other. This repair in essence is a primary closure of the defect. Standing cutaneous deformities resulting from skin and mucosal advancement were resected along the vermilion border. The resulting repair did not compromise the width or the topography of the philtrum.

FIGURE 9-24 A, A 1.5 × 1-cm skin and vermilion defect of upper lip. B, Superiorly and inferiorly based advancement flaps planned for repair of wound. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformities marked with vertical lines along vermilion border. C, Skin flap dissected. D, Vermilion and mucosal flap dissected. E, Wound approximated. F, Postoperative view at 6 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 6

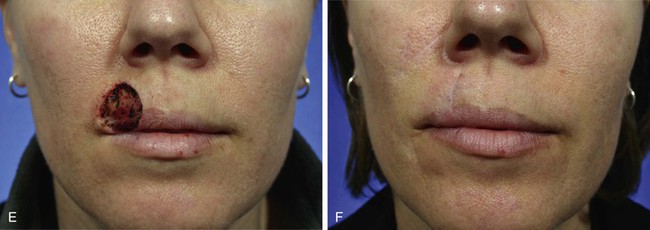

Advancement flaps are very useful for reconstructing skin defects of the upper and lower lip. Figure 9-25 shows a 1.4 × 1.5-cm circular defect of the central upper lip and vermilion after micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma. This defect could have been converted to a full-thickness lip defect and repaired by primary wound closure in a vertical orientation, which would have resulted in a need to excise a considerable section of exposed orbicularis oris. Other choices for reconstruction included the use of a local flap in the form of transposition or advancement.

FIGURE 9-25 A, A 1.5 × 1.4-cm skin and vermilion defect of central upper lip. Horizontal lines along vermilion-cutaneous border mark planned incisions for advancement flaps in T-plasty repair. Small vermilion advancement flap planned for repair of vermilion component of defect. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) marked for excision. B-D, Flaps incised and approximated, and SCD excised. E, F, Preoperative and 16-month postoperative views. Scar was dermabraded, causing hypopigmentation of central lip skin.

After healing, it was noted that the Cupid’s bow was absent. Cupid’s bow is an important aesthetic contour of the central upper lip, especially in young women. To restore the Cupid’s bow, revision surgery was performed in which a midline V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island skin flap of the philtrum was advanced inferiorly. After healing, the lip scars were dermabraded. Unfortunately, this resulted in an unfavorable appearance because of discrepancies of skin color and texture between the dermabraded area and the native lip skin.

The skin defect shown in Figure 9-26 had a similar location to that shown in Figure 9-25. Both defects were located within the philtrum of the upper lip; however, the defect shown in Figure 9-26 was smaller (1.6 × 1-cm) and involved less of the cutaneous portion and more of the vermilion portion of the lip. A V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap is another method of repairing skin defects of the upper lip that are 1 cm or smaller in size and located in the midline at the vermilion border. As shown in Figure 9-26, the island advancement flap was based on the underlying orbicularis oris. The flap was advanced inferiorly to the border of the diminutive vermilion defect. No advancement of the vermilion was necessary. The use of this flap enabled restoration of the natural double convexity of the Cupid’s bow. The flap also maintained the natural width of the philtrum. Primary repair of this wound would have narrowed the philtrum and would have eliminated the Cupid’s bow.

FIGURE 9-26 A, A 1.6 × 1-cm skin and vermilion defect of upper lip. V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap designed for repair of wound. Mucosal advancement flap marked. B, C, V-Y flap incised. Proximal and distal thirds of flap are freed from underlying muscle attachments. Flap advanced inferiorly to recipient site. Planned mucosal advancement flap not used. D-G, Preoperative and 7-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

Case 7

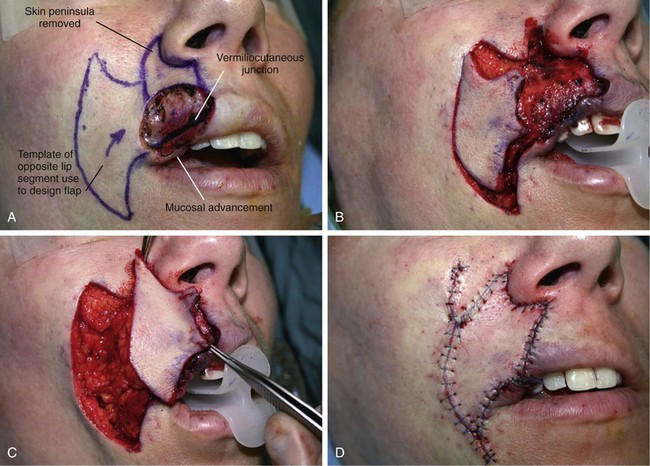

A 43-year-old woman had micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma of the upper lip. Her defect measured 3 × 2.5-cm and involved the skin and vermilion of the lateral lip. The defect was confined to the aesthetic region of the lip. The reconstructive options using a local flap included flaps designed as transposition, rotation, or advancement. A transposition flap harvested from the cheek was not the best option because, by necessity, the flap would have crossed the melolabial crease at right angles to the crease. This would have resulted in a scar that was perpendicular to RSTLs, which would have disrupted the continuity of the melolabial fold. As discussed earlier in this chapter, skin defects involving the lip and cheek adjacent to the alar base are effectively reconstructed with subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flaps. Such a flap was selected for this repair (Fig. 9-27). Most of the remaining skin of the lateral lip aesthetic unit was removed to place scars in aesthetic boundaries. This included the removal of the narrow skin peninsula between the superior melolabial fold and the ala.12 An exact template was designed of the cutaneous defect resulting from micrographic surgery and the planned additional skin removal superior to the defect. The template was used to design a subcutaneous tissue pedicled V-Y advancement flap. The vermilion component of the defect was repaired with a mucosal advancement flap developed from the oral aspect of the lip.

FIGURE 9-27 A, A 3 × 2.5-cm skin and vermilion defect of lateral upper lip. Skin superior to defect marked for excision to place scar in alar-facial sulcus. V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle advancement flap designed from template of opposite lip aesthetic unit for repair. Oral mucosa advanced outward (white arrow) to reconstruct missing vermilion. B-D, Island flap based on subcutaneous tissue pedicle advanced to recipient site. Mucosal advancement flap sutured to inferior border of island flap. E-H, Preoperative and 31-month postoperative views. Contouring of flap and several scar revisions including Z-plasties performed.

The flap was undermined in the subcutaneous plane to release the attachments between the flap skin and the orbicularis oris. The flap was left attached to the subcutaneous fat lateral to the modiolus. This fat served as the pedicle of the flap and had sufficient mobility to allow advancement of the flap into the defect. The mobility of the flap on its fat pedicle is well demonstrated in Figure 9-27C. The flap was dissected by the methods discussed in detail in an earlier section of this chapter. Because of the complexity of this defect, the patient required subsequent contouring of the V-Y advancement flap and revision of the vertical portion of the lip scar.13 By replacement of the skin peninsula between the melolabial fold and the ala, scars are better camouflaged than if the skin peninsula is not replaced with the V-Y advancement flap.

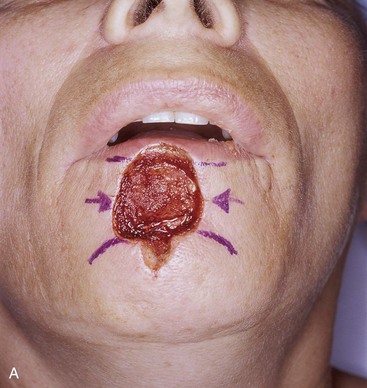

Case 8

A 63-year-old woman was treated for a recurrent basal cell carcinoma of the lower lip by micrographic surgery. Resection of the tumor left a 3 × 2.5-cm skin defect of the central lip. An option for reconstruction included converting the defect to a full-thickness excision and performing primary wound closure. This had the advantage of not requiring a flap for repair, but it would have significantly reduced the size of the oral stoma. For this reason, bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps were designed, placing borders of the flaps along the vermilion and within the mental crease (Fig. 9-28). The flaps were elevated in the subcutaneous plane, releasing flap skin from its tightly adherent attachments to the orbicularis oris. Standing cutaneous deformities were excised along the superior border of the flaps within the vermilion on either side of the midline. The standing cutaneous deformities at the inferior border of the flaps were excised together in the midline, causing the scar to extend downward slightly into the chin. Because the repair was under considerable wound closure tension, some hypertrophic scarring occurred, necessitating a subsequent scar revision. The final result of the reconstructive effort is seen in Figure 9-28C.

FIGURE 9-28 A, A 3 × 2.5-cm skin defect of lower lip. Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps designed for repair of wound. Superior border of flaps designed along vermilion-cutaneous border. Inferior border of flaps designed in mental crease. B, Flaps approximated. Standing cutaneous deformities excised superiorly in vermilion on either side of midline and inferiorly at midline. C, Postoperative view at 9 months. Revision of scars performed 4 months after initial reconstruction.

Defects of the lower lip of similar size to this case may often be repaired in the very elderly by converting the defect into a full-thickness wedge excision of the lip and closing the wound primarily. Elderly patients have a greater redundancy of lip tissue, and resection of one-third to one-half of the total width of the lower lip is frequently possible without causing microstomia. An example of this is shown in Figure 9-29. A 2 × 2-cm skin defect of the lower lip in a 79-year-old man was converted to a full-thickness elliptical excision and primary wound closure was performed. Although the vertical scar is lengthy, the aesthetic result is acceptable.

Case 9

A 45-year-old woman presented with a 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of the chin after micrographic surgery for a basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 9-30). This defect could have been repaired with bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps in the form of an H-plasty or O-T repair (T-plasty) or by an O-Z repair using bilateral rotation flaps. Perhaps imprudently, bilateral V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flaps were used for the repair. Although the superior scar resulting from the reconstruction is in RSTLs, the inferior scar is not. The scars have a depressed contour, and considerable trap-door deformity is present. The author has learned from experience that small (less than 2 cm) skin defects of the chin are not ideal for repair with island advancement flaps. This may be related to the topography of the chin. It may also be related to the tightly adherent skin attachments to the underlying musculature of the chin. However, larger defects of the chin may be reconstructed with V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flaps with acceptable aesthetic results. These flaps recruit the remaining skin of the chin in addition to adjacent cheek skin to create larger flaps compared with flaps confined solely to the chin aesthetic region (Fig. 9-31). Large island flaps tend to develop less trap-door deformities than smaller flaps of similar design.

FIGURE 9-30 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of chin. Bilateral V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle advancement flaps designed for repair of wound. B, Flaps approximated. C, Postoperative view at 6 months. No revision surgery performed.

FIGURE 9-31 A, A 6 × 5-cm skin defect of chin. Bilateral V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flaps designed for wound repair. Vertical lines represent planned skin excision. B, C, Flaps incised and advanced.

Small to medium-sized (3 cm) cutaneous defects confined to the chin are best repaired with bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps. An example of this is shown in Figure 9-32. The defect measured 1.5 × 1.5-cm and was closed by an O-T repair. The skin of the chin is inelastic, which may cause wound repair to be under relatively high wound closure tension. In addition, the chin has a convex surface. Flaps advanced over this convexity require greater skin movement for a given size defect than for a defect of the same dimension located on a flat surface, such as the cheek. Figure 9-32B demonstrates this fact. The effective length of the two advancement flaps was reduced by the convexity of the chin, leaving a secondary defect superior to the flaps. The secondary defect was repaired by wide undermining and inferior advancement of the skin of the lower lip.

FIGURE 9-32 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of chin. Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps (T-plasty) designed for repair. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity marked with horizontal lines. B, Flaps dissected and apposed with single suture. Effective length of flaps reduced by convexity of chin, causing secondary defect to develop superior to flap borders. C, Secondary defect closed by inferior advancement of lower lip skin.

References

1. Johnson, TM, Nelson, BR. Aesthetic reconstruction of skin cancer defects using flaps and grafts. Am J Cosmetic Surg. 1992; 9:253.

2. Swanson, NA. Atlas of cutaneous surgery. Boston: Little, Brown; 1987.

3. Salache, SJ, Grabski, WJ. Flaps for the central face. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1990.

4. Juri, J, Juri, C. Cheek reconstruction with advancement-rotation flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 1981; 8:223.

5. Bennett, RG. Local skin flaps on the cheeks. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991; 17:161.

6. Salache, SJ, Jarchow, R, Feldman, BD, et al. The suspension suture. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1978; 13:973.

7. Burget, GC, Menick, FJ. Aesthetic restoration of one-half the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 78:583.

8. Khan, JA. Subcilial sliding skin muscle flap repair of anterior lamella lower eyelid defects. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991; 17:167.

9. Skouge, JW. Upper lip repair: the subcutaneous island pedicle flap. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990; 16:63.

10. Anderson, KW, Baker, SR, Lowe, L. Treatment of head and neck melanoma, lentigo maligna subtype. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001; 3:202.

11. Anderson, KW, Baker, SR. Management of early lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna of the head and neck. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2003; 11:93.

12. Burget, G, Hsiao, YC. Nasolabial rotation flaps based on the upper lateral lip subunit for superficial and large defects of the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012; 130:556.

13. Griffin, GR, Weber, S, Baker, SR. Outcomes following V-Y advancement flap reconstruction of large upper lip defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012; 14:193.