Chapter 45 Advanced nursing roles

Advancing nursing practice is a global phenomenon: in the context of the Australian experience, this has evolved over the past three and a half decades. The evolution of advance nurse practice is an ongoing process moving nursing practice forward for the benefit of the patient.1 This change of practice is directly related to changes in the delivery of healthcare services and the implementation of new models of patient-focused care. An important driver in the development of the advance practice nurse is the political demand to meet government-set performance indicators and benchmarks aimed to reduce emergency department waiting times and patient length of stay and to increase patient satisfaction.2 Another factor that has contributed to evolving advance practice is medical and nursing workforce shortages and skill mix problems. These developments have provided the impetus for emergency nurses to take on new opportunities to develop and increase their scope and complexity of practice in the field of emergency medicine. These advance nursing roles are now core roles that work with and support the medical and clerical staff to expedite the patient’s journey through the emergency department.

THE TRIAGE NURSE

The patient’s journey in the emergency department begins at triage. Triage is an essential function in the delivery of care in all emergency departments. It is the point at which emergency care begins. Triage is a brief clinical assessment that determines the urgency of treatment and the time sequence in which patients should be seen in the emergency department. The purpose of the triage system is to ensure safe quality of care and equity of access to health services. In all healthcare environments, the triage process is underpinned by the premise that a reduction in the time taken to access definitive medical care will improve patient outcomes.3

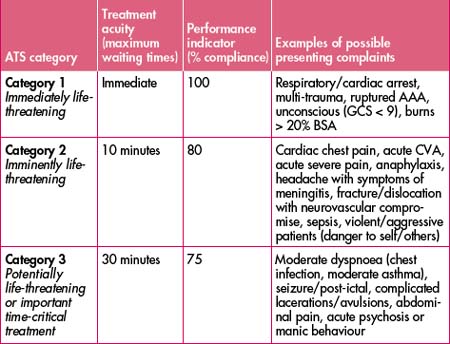

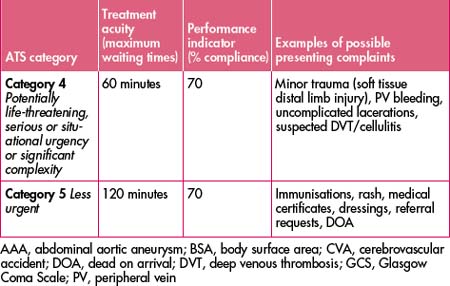

In Australasian emergency departments a standardised triage system known as the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) is the primary clinical tool for ensuring patients are seen in a timely manner, commensurate with their clinical urgency. The practical application of the ATS is the process by which the triage nurse assesses a patient’s presenting complaint, which is identified by a brief history of the presenting illness or injury. Triage decisions using the scale are made on the basis of observation of general appearance, focused clinical history and physiological data.4 This decision-making process may also require consultation and discussion with medical staff.

In practical terms triage refers to two domains, which are:

Domain 1. The ATS has five levels of acuity that categorise patients according to a rating scale from 1 to 5. (Also see Chapter 39, ‘Psychiatric presentations’, Table 39.1 Mental health triage.)

Table 45.1 ATS categories for treatment acuity, performance thresholds and examples of possible presenting problems

Domain 2. Time-to-treatment criteria attached to the ATS.

Please refer to Table 45.1 for triage examples.

There are five core components for a nurse undertaking the role of triage nurse:

Step 3. Always ask the question: ‘Does this person look sick?’

Step 5. Other conditions in which timely intervention may significantly influence outcomes (such as thrombolysis, an antidote or management of acid or alkali splash to eye) must also be detected at triage.

Step 6. Timely access to emergency care can improve patient outcomes.

Step 7. Early identification of physiological abnormality at triage can inform focused ongoing medical assessment and investigation.6

CLINICAL INITIATIVES NURSE (CIN)

Nurses working at CIN level should have:

The CIN role enables the nurse to commence patient treatment via pre-approved standing orders for specific presentations under the supervision of an emergency department registrar or consultant.

Box 45.1 Example 1. Patient presenting with an ankle fracture

AGED SERVICE EMERGENCY TEAM (ASET)

The specific objectives of this team include:

An example of how the ASET functions is described in Box 45.2.

Box 45.2 Example 2. 80-year-old female presenting with recurrent falls

ASET nurse undertakes comprehensive assessment including:

RAPID ASSESSMENT TEAM (RAT)/IMMEDIATE INITIATION OF CARE (IIOC)

There are a variety of names and abbreviations, such as RAT and IIOC, which describe models of rapid assessment and treatment within the emergency department. These models involve having a team of a senior doctor and nurse meeting patients as they arrive. What they actually do for each patient will depend on the nature and seriousness of the problem, as well as the prevailing patient flow constraints at the time.

The specific objectives of these teams are to:

The two biggest dangers of these models are:

An example of how the RAT/IIOC works is set out in Box 45.3.

THE NURSE PRACTITIONER (NP)

The nurse practitioner is a registered nurse educated and authorised to function autonomously and collaboratively in an advanced and extended clinical role. The nurse practitioner role includes assessment and management of patients using nursing knowledge and skills and may include, but is not limited to, the direct referral of patients to other healthcare professionals, prescribing medications and ordering diagnostic investigations. The scope of practice of the nurse practitioner is determined by the context in which the nurse practitioner is authorised to practise and approval of nurse practitioner guidelines at the local level. The nurse practitioner will refer the patient to the medical officer if there is any evidence of symptoms outside their scope of practice.

Two examples of the nurse practitioner scope of practice are given in Boxes 45.4 and 45.5. The first example outlines the assessment and management of an acute sore throat. The second outlines the assessment and management of a patient with central chest pain.

Box 45.4 Example 4. Patient presenting with acute sore throat

Presenting complaint as stated by the patient or significant other:

The nurse practitioner will be continually assessing and initiating:

The nurse practitioner will also document the following as part of the clinical assessment:

The general assessment will consist of:

Management will consist of either a medical pathway or a nurse practitioner pathway.

Paracetamol/aspirin (may be gargle)

Antibiotic therapy if there is:

Box 45.5 Example 5. Patient presenting with chest pain

Presenting complaint: as stated by the patient or significant other.

History of presenting complaint and assessment will include the following (mnemonic—CHEST PAIN9);

While going through the above, the nurse practitioner will be continually assessing and initiating:

The nurse practitioner will also document the following as part of the clinical assessment:

The general management of chest pain will consist of diagnosis and risk stratification and management as per local protocols and pathways for high, intermediate and low risk. (See Chapter 7, ‘Acute coronary syndromes’.)

CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; SOBOE, shortness of breath on exertion

PEARLS OF WISDOM

It is important to appreciate that approximately 75% of your diagnosis comes from information gained at history taking, leaving only approximately 25% originating from your physical examination, diagnostics tests etc.10

1 Por J. A critical engagement with concept of advancing nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Management. 2008;16:84-90.

2 Hudson P., Marshall A. Extending the nursing role in emergency departments: challenges for Australia. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2008;11:39-48.

3 Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Emergency Triage Education Kit. 2007; p 4. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/publicat.html.

5 CENA. Position statement triage nurse. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2007;10:93-95.

6 Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Emergency Triage Education Kit. 2007:18.

7 NSW Health. Clinical initiatives nurse guidelines: the emergency nurses advisory group. 2002.

8 Dennis M., Waters W., Shanahan M. Emergency department nurse practitioner clinical practice guidelines. Greater Southern Area Health Service, NSW Department of Health. 2006.

9 Newberry L., Barret G.K., Ballard N. A new mnemonic for chest pain assessment. J Emerg Nurs. 2005;31(1):84-85.

10 Peterson M.C., Holbrook J.H., von Vales D., et al. Contributions of the history, physical examination and laboratory investigations in the medical diagnosis. West J Med. 1992;156:163-165.

Australasian College for Emergency Medicine website: http://www.acem.org.au.

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Emergency Triage Education Kit. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/publicat.html.

College of Emergency Nursing Australasia website: http://www.cena.org.au.

Curtis K., Friendship J., Ramsden C. Emergency and trauma nursing. Elsevier Australia; 2007.

Dolan B., Holt L. Accident and emergency. Theory into practice. Elsevier Limited; 2000.

Fry M., Holdgate A. Nurse initiated intravenous morphine in the emergency department: efficacy, rate of adverse events and impact on time to analgesia. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2002;14(3):249-254.

Hodkinson H. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age and Ageing. 1972;1:233-238.

Inouye S.K., et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for the detection of delirium. Ann Int Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

National standards and competency for a nurse practitioner. Online. Available: http://www.anmc.org.au/docs/Competency_Standards_for_the_Nurse_Practitioner.pdf.

NSW Health. State authorisation. Requirements for nurse/mid-wife practitioners and the scope of practice/clinical guidelines. Online. Available: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2005/pdf/PD2005_556.pdf.

Prince of Wales Hospital. In their shoes (communication training DVD). 2005.