Chapter 2 Advanced history taking

Most complaints about doctors relate to the failure of adequate communication.1,2 Encouraging patients to discuss their major concerns without interruption enhances satisfaction and yet takes little time (on average 90 seconds).3,4 Giving premature advice or reassurance, or inappropriate use of closed questions, badly affects the interview.

Taking a good history

Communication and history taking skills can be learnt but require constant practice. Factors that improve communication include use of appropriate open-ended questions, giving frequent summaries, and the use of clarification and negotiation.3,4 See Table 2.1.

| 1 Ask open questions to start with (and resist the urge to interrupt), but finish with specific questions to narrow the differential diagnosis. |

| 2 Do not hurry (or at least do not appear to be in a hurry, even if you have only limited time). |

| 3 Ask the patient ‘What else?’ after he or she has finished speaking, to ensure that all problems have been identified. Repeat the ‘What else?’ question as often as required. |

| 4 Maintain comfortable eye contact and an open posture. |

| 5 Use the head nod appropriately, and use silences to encourage the patient to express him- or herself. |

| 6 When there are breaks in the narrative, provide a summary for the patient by briefly re-stating the facts or feelings identified, to maximise accuracy and demonstrate active listening. |

| 7 Clarify the list of chief or presenting complaints with the patient, rather than assuming that you know them. |

| 8 If you are confused about the chronology of events or other issues, admit it and ask the patient to clarify. |

| 9 Make sure the patient’s story is internally consistent and, if not, ask more questions to verify the facts. |

| 10 If emotions are uncovered, name the patient’s emotion and indicate that you understand (e.g. ‘You seem sad’). Show respect and express your support (e.g. ‘It’s understandable that you would feel upset’). |

| 11 Ask about any other concerns the patient may have, and address specific fears. |

| 12 Express your support and willingness to cooperate with the patient to help solve the problems together. |

The differential diagnosis

This method of history taking is called, rather grandly, the hyopthetico-deductive approach. It is in fact used by most experienced clinicians. History taking does not mean asking a series of set questions of every patient, but rather knowing what questions to ask as the differential diagnosis begins to become clearer.

Fundamental considerations when taking the history

As any medical interview proceeds, the clinician should keep in mind four underlying principles:

Personal history taking

Certain aspects of history taking go beyond routine questioning about symptoms. This part of the art needs to be learnt by taking lots of histories; practice is absolutely essential. With time you will gain confidence in dealing with patients whose medical, psychiatric or cultural situation makes standard questioning difficult or impossible.5,6

If an emotional response is obtained, use emotion-handling skills (NURS) to deal with this during the interview (see Table 2.2). Name the emotion, show Understanding, deal with the issue with great Respect, and show Support (e.g. ‘It makes sense you were angry after you husband left you. This must have been very difficult to deal with. Can I be of any help to you now?’).

| • Name the emotion |

| • Show Understanding |

| • Deal with the issue with Respect |

| • Show Support |

It is important for the history taker to maintain an objective demeanour, particularly when asking about delicate subjects such as sexual problems, grief reactions or abuse. It is not the clinician’s role to appear judgmental about patients or their lives.

The formal psychological or psychiatric interview differs from general medical history taking. It takes considerable time for patients to develop rapport with, and confidence in, the interviewer. There are certain standard questions that may give valuable insights into the patient’s state of mind (see Questions boxes 2.1–2.3). It may be important to obtain much more detailed information about each of these problems, depending on the clinical circumstances (see Chapter 12).

Questions box 2.3

The sexual history

The sexual history is important, but these questions are not appropriate for all patients, at least not at the first visit when the patient has not yet had time to develop confidence and trust. The patient’s permission should be sought before questions of this sort are asked. This request should include some explanation as to why the questions are necessary.7

A sexual history is most relevant if there is presentation with a urethral discharge, painful urination (dysuria), vaginal discharge, a genital ulcer or rash, abdominal pain, pain on intercourse (dyspareunia), or anorectal symptoms, or if human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis are suspected.8

Ask about the last date of intercourse, number of contacts, homosexual or bisexual partners, and contacts with sex workers. The type of sexual practice may also be important: for example, oroanal contact may predispose to colonic infection, and rectal contact to hepatitis B or C, or HIV.

It is also often relevant to ask diplomatic and ‘matter of fact’ questions about a history of sexual abuse. One way to start is: ‘You may have heard that some people have been sexually or physically victimised, and this can affect their illness. Has this ever happened to you?’ Such events may have important and long-lasting physical and psychological effects.9

Cross-cultural history taking

If the patient’s first language is not the same as yours, he or she may find the medical interview very difficult. Maintain eye contact (unless this is considered rude in the cultural context) and be attentive as you ask questions.10

Recent concepts in indigenous health care include the notions of cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity and cultural safety.11,12 Cultural awareness can be thought of as the first step towards understanding the rituals, beliefs, customs and practices of a culture. Cultural sensitivity means accepting the importance and roles of these differences. Cultural safety means using this knowledge to protect patients and communities from danger, and making sure that there is a genuine partnership between the health workers and their indigenous patients. These skills have general application for all cultural groups but vary in detail from one to another.

The ‘uncooperative’ or ‘difficult’ patient and the history

Most clinical encounters are a cooperative effort on the part of the patient and clinician. The patient wants help to find out what is wrong and to get better. This should make the meeting satisfying and friendly for both parties. However, interviews do not always run smoothly.13 Resentment may occur on both sides if the patient seems not to be taking the doctor’s advice seriously, or will not cooperate with attempts at history taking or examination. Unless there is a serious psychiatric or neurological problem that impairs the patient’s judgment, taking or not taking advice remains his or her prerogative. The clinician’s role is to give advice and explanation, not to dictate. Indeed, it must be realised that the advice may not always be correct. Keeping this in mind will help prevent that most unsatisfactory and unprofessional of outcomes—becoming angry with the patient.

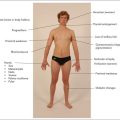

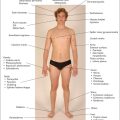

History taking for the maintenance of good health

Part of the thorough assessment of patients includes obtaining and conveying some idea of what measures may help them maintain good health (Questions box 2.4). This includes a comprehensive approach to the combination of risk factors for various diseases, which is much more important than each individual risk factor. For example, advising a patient about the risk of premature cardiovascular disease will involve knowing about the family history, smoking history, previous and current blood pressure, current and historical cholesterol levels, dietary history, assessment for diabetes mellitus and how much exercise the patient undertakes.

Questions box 2.4

Questions related to the maintenance of good health

Certain questions can be helpful in making a diagnosis of alcoholism; these are referred to as the CAGE questions (see Chapter 1). Another approach is to ask, ‘Have you ever had a drinking problem?’ and ‘Did you have your last drink within the last 24 hours?’ The patient who answers ‘yes’ to both questions is likely to be a high-risk drinker.

The elderly patient

Mental state

Delirium refers to confusion and altered consciousness. Don’t confuse this with dementia, where consciousness is not altered but there is progressive loss of long-term memory and other cognitive functions. Perform a mini-mental examination (refer to Chapter 12) and record the score.

Evidence-based history taking and differential diagnosis

A symptom typical of a certain condition will increase the likelihood of the diagnosis by a certain percentage. If the prevalence of the condition is already high, a high likelihood ratio (LR) should bring that condition towards the top of the differential list. For example, a patient’s description of ‘typical angina’ has a strong LR of 5.8 for the diagnosis of significant coronary artery disease. This would make the diagnosis highly likely in a patient from a population with a high prevalence of coronary disease (e.g. a man over the age of 50 with typical anginal chest pain) but still very unlikely in someone from a very low risk population (e.g. a 19-year-old woman). Likelihood ratios are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

The clinical assessment

After the physical examination, the interview with the patient concludes with an assessment by the clinician of what the diagnosis or possible diagnoses are, in order of probability.14 This will, not unreasonably, be the most important part of the whole process from the patient’s point of view.

The explanation must relate to the patient’s symptoms or perception of the problem. The clinician should explain how the symptoms and any examination findings relate to the diagnosis. For example, if a patient presents with dyspnoea, the clinician should begin by saying, ‘I believe your shortness of breath is probably the result of pneumonia, but there are a few other possibilities’. The complexity of the explanation will depend on the clinician’s understanding of the patient’s ability to follow any technical aspects of the diagnosis. The patient’s desire for a detailed explanation is also variable, and this must be taken into account.

1. Nardone DA, Johnson GK, Faryna A, Coulehan JL, Parrino TA. A model for the diagnostic medical interview: nonverbal, verbal, and cognitive assessments. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:437-442.

2. Balint J. Brief encounters: speaking with patients. Ann Intern Med.. 1999;131:231-234.

3. Simpson M, Buchman R, Stewart M, et al. Doctor–patient communication: the Toronto consensus statement. BMJ. 1991;303:1385-1387.

4. Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes in review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423-1433. The outcome of an illness can be affected by the first part of the medical intervention, the doctor’s history taking

5. Smith RC, Hoppe RB. The patient’s story: integrating the patient- and physician-centered approaches to interviewing. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:470-477. Patients tell stories of their illness, integrating both the medical and psychosocial aspects. Both need to be obtained, and this article reviews ways to do this and to interpret the information

6. Ness DE, Ende J. Denial in the medical interview: recognition and management. JAMA. 1994;272:1777-1781. Denial is not always maladaptive, but can be addressed using appropriate techniques. This is a good guide to the problem and process

7. Ende J, Rockwell S, Glasgow M. The sexual history in general medicine practice. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:558-561. This study emphasises the importance of obtaining the sexual history as a routine

8. Furner V, Ross M. Lifestyle clues in the recognition of HIV infection. How to take a sexual history. Med J Aust. 1993;158:40-41. This review guides the shy medical student through this difficult task

9. Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Leserman J, et al. Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:782-794. Abuse is common, has occurred more often in women, causes a poorer adjustment to illness and usually remains a fact not discussed with the doctor

10. Qureshi B. How to avoid pitfalls in ethnic medical history, examination, and diagnosis. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:65-66. Provides information on transcultural issues, including taboos on anogenital examinations

11. Ngyuen T. Patient centered care. Cultural safety in indigenous health. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37(12):900-904.

12. Ramsden I. Cultural safety. N Z Nurs J. 1990;83:18-19.

13. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:833-837. Describes groups of patients that induce negative feelings, and provides important management insights

14. Hampton JR, Harrison MJG, Mitchell JAR, Pritchard JS, Seymour C. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and the laboratory to the diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. BMJ. 1975;2:486-489. In 66 out of 80 new patients the diagnosis based on the history was correct; physical examination was useful in only 7 patients and laboratory tests in another 7. Take a good history: it’s the key to success!

Billings JA. The clinical encounter: a guide to the medical interview and case presentation, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby Year Book Medical Publishers; 1999.

Cohen-Cole SA. The medical interview: the three function approach, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2000.

Coulehan JL, Block MR. The medical interview: a primer for students of the art, 4th edn. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 2001.

Mysercough PR. Talking with patients—a basic clinical skill, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.