CHAPTER 72 Adult Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis by definition is an anterior or posterior translational displacement of one vertebra on another. In the adult, this occurs in the lumbar spine as a result of defects in the bony architecture, trauma, or degeneration.1–3 Due to the body’s center of gravity being anterior to the lumbosacral joint, slippage occurs as the lumbar spine rotates around the sacral dome. The age of the patient when these defects occur and the individual’s sagittal alignment of the spine determine to what degree the deformity progresses.

Classification/Natural History

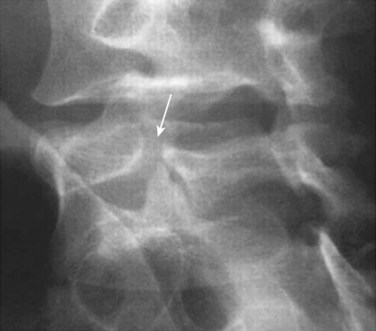

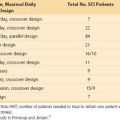

Adult spondylolisthesis presents in predominately two patterns: the isthmic variety, which involves abnormalities of the pars intra-articularis (Fig. 72–1), and the degenerative variety, which occurs as a result of lumbar spondylosis with its disc degeneration and instability causing a physiologic unwinding of the facets in the sagittal plane.4–6 (Fig. 72–2) This section concentrates on the isthmic variety.

Fredrickson and colleagues7 prospectively followed 500 elementary students and found a 4.4% incidence of spondylolysis and a 2.6% of spondylolisthesis at age 6. After reaching adulthood, the incidence of spondylolysis was 5.4% and spondylolisthesis was 4%. Healing of the pars did not routinely occur and slippage occurred throughout both decades covered, with the greatest change occurring during the adolescent years.

Pathophysiology

Incidence

The incidence of defects in the pars interarticularis or isthmic variety of spondylolisthesis is 4% to 6% in the general population.8–10 It is more common in males and more common at the L5-S1 level. Fifty percent present with only spondylolysis with no slippage. Even though the rate of occurrence is lower in females, when it occurs, there is a tendency for a higher rate of progression of the slippage. The pars defect usually occurs between 5 and 7 years of age and is not seen until erect posture is achieved. The incidence varies according to race with 6.4% in white American males, 2.8% in black males, 2.3% in white females, and 1.1% in black females. Eskimos have been shown to have a rate as high as 50%.11 A genetic tendency has also been shown to exist in patients with spondylolysis with a higher incidence than normal being reported in other family members.12 Slippage occurring as a result of degenerative etiology is more common in females older than the age of 40.

Mechanism of Injury

Spondylolisthesis as a result of defects in the pars intra-articularis has been subdivided into three categories by Wiltse2,13 (isthmic spondylolisthesis). Subtype A occurs as a result of fatigue failure of the pars and is evident by a complete defect or separation of the bone. Subtype B or an elongated pars occurs as a result of repeated microtrauma with subsequent healing of the bone as the slippage gradually occurs. Subtype C is an acute pars fracture.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

The cross-sectional anatomy of the pars at each level in the lumbar spine contributes to the increased incidence as to which level the breaks occur.14 The pars is fairly large in diameter in the upper lumbar vertebra and relatively thin at the L5 level. A congenitally dysplastic pars combined with upright posture increases the forces concentrated across the pars with extension and can lead to stress fractures. Sports activities that place loaded extension across the lumbosacral junction increase the forces across the pars and increase the chance of a stress fracture occurring in the pars with the smallest cross-sectional area. Facet joints oriented more coronally cephalad to the lumbosacral junction have been shown to be present in patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis.15 Attempts to heal the pars defect lead to increased cartilage and fibrous tissue further compromising the lateral recess and compressing the exiting nerve root. Slips occurring as a result of acute trauma cause destruction of the bony arch or facet, as well as the soft tissue components of the disc, annulus, and ligaments.

Diagnosis

History

Most people with isthmic spondylolisthesis are asymptomatic.16 Those who do become symptomatic usually present with back pain, leg pain, or a combination. Complaints of back pain with activity and relieved with recumbency are often described. The leg pain numbness or paresthesia described by symptomatic patients is predominately dermatomal in distribution if the nerve is being compressed in the lateral recess at the level of the pars defect. It is described as scleradermal if referred into the broad region of the buttock or posterior thigh, which occurs usually as a result of the disc degeneration that often accompanies the pars defect.

Imaging

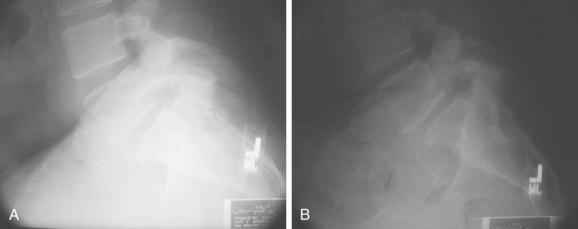

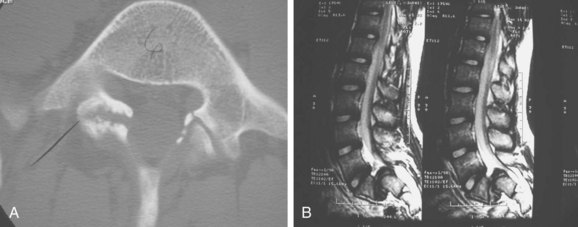

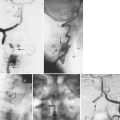

Radiographic evaluation should consist of anteroposterior and lateral flexion-extension radiographs. Having both a supine and standing lateral radiograph is important.9 This combination will allow the determination of translational instability (Fig. 72–3). If necessary, oblique radiographs can be obtained. This will better delineate the integrity of the pars intra-articularis. Computed tomography (CT) scans will provide excellent bony details of the pathology, and the magnetic resonance scan will give much better delineation of the soft tissue abnormalities associated with the problem (Fig. 72–4).

SPECT scans can be used for delineation of the problem if suspected clinically and radiographs are inconclusive. This study can also be helpful in determining whether or not the defect is acute or chronic. Spina bifida occulta has been reported to be as high as 70% in patients with an isthmic defect.17 Scoliosis is noted in 5% to 7% of patients with spondylolisthesis and usually presents as a long C-shaped curve rather than those of a rotated variety.18

Treatment Options

Conservative Treatment

Initial treatment in the acute phase should consist of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), pain management, and physiotherapy. Exercises should be directed to strengthen the abdominal and paraspinal musculature, as well as a stretching program to improve flexibility. Weight loss and aerobic conditioning programs should be added if necessary. Bracing can be used as an adjunct to the physiotherapy.19 The use of steroid injections into the facet joint and epidural space are helpful in the acute phase but are not advocated for long-term use due to potential complications of this medication with long-term use. The use of narcotic medications other than in the acute phase should be avoided because they adversely affect recovery and can lead to prolonged disability. The majority of patients will completely recover within 3 months of onset and can be allowed to return to full activity. Incorporation of a daily exercise routine for maintenance of muscular strength and flexibility should be encouraged. If this fails, surgical options should be considered.

Surgical Goals

The goals of surgical treatment in spondylolisthesis consist of stabilization of the affected levels along with decompression of the neural elements. Stabilization prevents further slippage of the vertebra. Decompression of the neural elements prevents further progression of the neural deficit and allows the present deficit the best chance to recover. Wiltse and colleagues20 reported that stabilization of segmental movement through the defect by fusion can result in improvement and resolution of the neural deficit by preventing the continued motion segment from irritating the neural tissues.

In the high-grade slips, the cosmetic problem that results from the posture and gait abnormalities can be an indication for the surgery. The significant risk of neurologic problems in this group of patients, should reduction be planned, must be carefully considered and presented when discussing this procedure with the patient.21–26

Contraindications for Surgical Repair

Relative contraindications for surgery because of expected poor outcome include patients who continue to smoke and have either disability or compensation claims.27,28 Those with previous multiple procedures for fusion or pseudarthrosis repair also have reported poor outcomes following surgery.

Surgical Options

Treatment options in isthmic spondylolisthesis consist of (1) a direct repair of the pars intra-articularis30–33; (2) decompression of the neural elements alone34–37; (3) decompression of the neural elements in conjunction with an in situ posterior lateral fusion32,38,39,40; (4) decompression of posterior lateral fusion with associated pedicular instrumentation28,39,41; and (5) decompression and reduction of the spondylolisthesis with instrumentation and interbody fusion.42–44

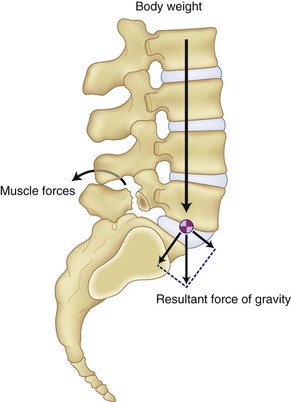

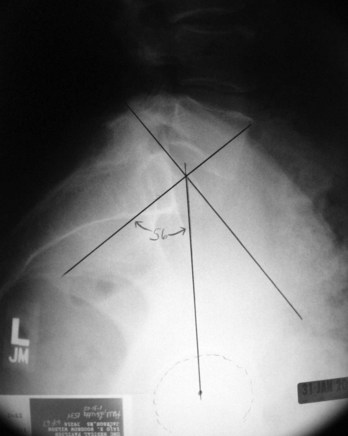

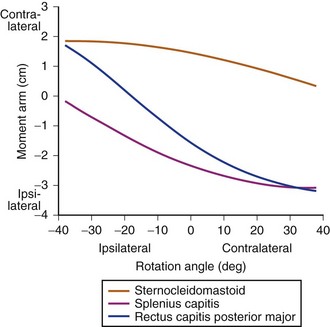

The progression of the slippage is a fairly complex biomechanical problem, which results from shear forces being placed across the segment as a result of the kyphotic deformity from the spondylolisthesis.45–47 The body weight acts as a vertical load creating a shearing moment, which is enhanced as result of the local kyphosis and results in anterior translation in the sagittal alignment, as the vertebra rolls over the sacral dome. The paraspinal muscles increase their tone in response to minimize the shear going across this segment, which can result in spasm with hyperlordosis often seen clinically (Fig. 72–5). Pelvic incidence seems to play a factor in the progression of the spondylolisthesis.48 Hansen and colleagues recently showed in their study a statistically significant increase in the chance of slippage as the pelvic incident angle increases.49 (Fig. 72–6) When compared with his control group without any spondylolisthesis, which had a 57-degree pelvic incidence angle, those patients with a low-grade spondylolisthesis had a pelvic incidence of 68.5 degrees, whereas those with high-grade slippage had a pelvic incidence angle of 79 degrees. This, in conjunction with the gravity across the locally kyphotic segment, tends to increase the shear forces across the affected segment and result in increased slippage.

Direct Repair of the Pars

Repair of the pars defect has been described using wire loops and screws combined with bone grafting.50 Morelos and Pozzo51 studied 32 patients treated with direct surgical repair and stabilization of the pars intra-articularis defect with a 3.4-year follow-up. This study group ranged in age from 18 to 54 years, and treatment consisted of resection of the Gill lesion with decompression of the nerve and grafting of the defect with internal fixation and compression of the pars defect. Good radiologic healing and good clinical outcome were reported in this group. Schlenzka52 also reported a group of patients treated with direct repair of the pars intra-articularis and, again, found good healing potential, as well as clinical outcome. When looking at these patients long term, the study reveals there to be no statistically significant difference in the outcome of those treated with direct pars repair when compared with patients who were treated with posterior lateral fusion. Furthermore, adjacent segment degeneration was about the same in those patients treated with direct pars repair when compared with those patients treated with the posterior lateral fusion. This tends to refute the concept that maintenance of the mobile segment would assist in the protection of the adjacent segment and lead to a better long-term overall outcome when compared with those treated with arthrodesis.

Seitsalo and colleagues53 studied the adjacent disc to the slipped segment in a group treated surgically with a posterolateral fusion compared with a conservatively treated group. The results revealed the rate of degeneration to be comparable between the groups with no correlation to back pain. This supports the premise that disc degeneration has individual genetic tendency and is not purely related to increased mechanical stresses. Similar findings of adjacent segment degeneration were reported by Hambly and colleagues.54

Decompression Alone

This treatment option should be reserved for the older population that presents with predominantly leg pain. With decompression of the neural elements, the radicular symptoms should resolve. Because the segment is stable, the likelihood of a progressive slip is minimized. Removal of the abnormal facet, loose lamina, and pars was first described by Gill.35 This involves decompression of the nerve by removing the fibrocartilage mass that occurs as the body attempts to heal the pars defect. This should be used only in patients who have had complete collapse of the disc space, who are stable, and who are older than 55 years of age. When patients are carefully selected for this modality, published studies show the outcome of this treatment to be good.34 In those patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis and stenosis, consideration of a posterior lateral fusion should be made due to the increased chance of slip progression following decompression.

Decompression and Posterolateral Fusion

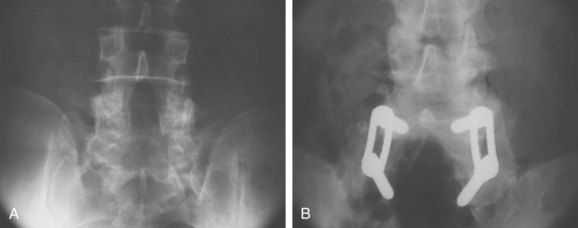

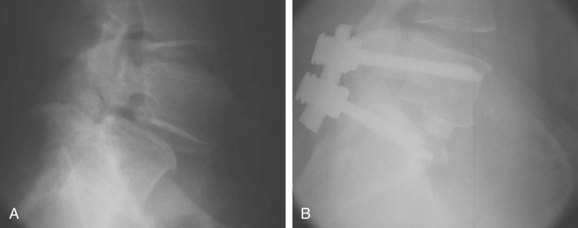

Decompression should be performed in exactly the same manner as described earlier with removal of the hypertrophied fibrocartilage pars lesion completely decompressing the exiting nerve root. Fusion should be considered in all patients younger than 30, as well as all those who have significant disc height remaining, which has been shown to increase the risk of further slippage following decompression. This particular treatment modality has been shown to be consistent for relief of leg pain and improvement in back pain. McGuire and Amundson28 have shown in a study of 27 patients who were treated with decompression and posterolateral autograft fusion to have excellent relief of their leg pain. Comparison of rigid internal fixation with in situ fusion was made in this group, which consisted of stable low-grade slips, and no statistical difference was found in the fusion rate of the instrumented versus the noninstrumented (Fig. 72–7). What is of interest in this particular study is that patients treated with fusion, whether instrumented or not, who were smokers had a 40% chance of a nonunion compared with nonsmokers. Those patients in the study with a resulting pseudoarthrosis were treated with repeat surgery for repair of the pseudoarthrosis and resulted in an overall fusion rate of 96%. Of this group, 67% returned to military duties and 33% were subsequently discharged from the military due to inability to continue their assigned-duty activities. The conclusions reached from the study were that instrumentation does not necessarily guarantee a fusion and fusion does not guarantee automatic clinical success. It further reinforced the fact that patients using tobacco products undergoing posterolateral fusion have a higher risk of nonunion. Swan and colleagues55 reported a study comparing posterolateral fusion to anterior-posterior fusion and found no difference in the outcome after 6 months. Their recommendation was to consider carefully the risk versus benefits before deciding to proceed with a combined procedure.55

Moller and Hedlund56 also report similar conclusions in their study of a similar group of patients.

Anterior Column Support and Posterior Stabilization

The use of transforaminal interbody fusions has also become popular. It allows the neural elements to be decompressed, as well as stabilization of the anterior column from a single posterior approach.57

The benefits of the transforaminal approach minimize the risk of neural compromise due to the fact that the grafts can be put in without undue traction on either the exiting or traversing nerve root because the entire facet and pars are removed. Great care, however, needs to be used to minimize potential risk to the exiting dorsal root ganglion. This technique provides the ability to achieve and maintain the reduction by releasing the soft tissues circumferentially. Pedicle screws are placed across the affected level, which allows distraction to occur while the disc space is being completely cleaned. Once bleeding cortical endplates are present, following removal of the discs, morcellized bone graft is packed anteriorly, followed by either a machined allograft or a composite cage, and the spine is realigned by bringing the cephalad vertebra back into alignment over the caudal vertebra and then compressing the construct, which re-establishes the anterior column support. This allows patients to be mobilized fairly quickly without the use of a brace (Fig. 72-8). Any reduction or disc distraction of the spondylolisthesis must be supported with bone or cage insertion for anterior column reconstruction.

In obese individuals, the anterior column support can provide better spinal support and allow a more rapid rehabilitation, which minimizes some of the potential complications of individuals with such body habitus.58,59

In a study published by Spruit and colleagues60 using posterior reduction with anterior interbody grafting, 12 patients with a 21% preoperative slip were reduced to 7% postoperatively. They report a 100% fusion rate with 75% of the patients being returned to their previous work. Molinari and colleagues61 found similar results in a military population treated with instrumentation and interbody fusion. Twenty-seven of thirty (90%) were able to remain on active duty with 19/30 returning to unrestricted military activity.

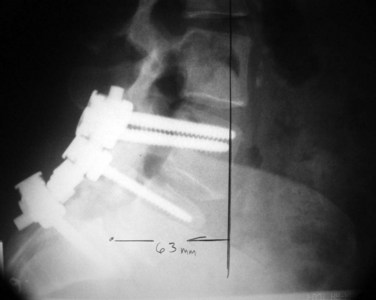

Kawakami and colleagues46 have noted that the outcome of surgically treated patients undergoing fusion seems to be improved with the reduction of the sagittal alignment of the spine. They noticed in this study that if the alignment of the L1 to S1 axis was less than 35 milliliters, the overall clinical outcome of these patients was statistically improved when compared with those greater than 35 milliliters (Fig. 72–9). The other possible benefit of reduction is the protection of the adjacent segment due to the correction of the kyphotic deformity at the level of the spondylolisthesis with the surgical reduction and fusion.

Reduction of High-Grade Spondylolisthesis/Spondyloptosis

Reduction of high-grade slips has been advocated by several authors to improve cosmesis, correct the severe slip angle, or improve the kyphosis that occurs locally with this entity.26 Most of the time this does not have to be done in adults with spondylolisthesis.62,63 Reduction of high-grade spondylolisthesis has been associated with a high rate of neural complications. These occur not only at the level of the slip but also at the more cephalad roots, as the dural sleeve is relatively lengthened with the reduction maneuver that puts these upper roots under tension.

Pearls

Pitfalls

Key Points

1 Wiltse LL. Spondylolisthesis: Classification and etiology. Symposium on the Spine. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1969. 143-168

This study gives an excellent overview of the classification of spondylolisthesis.

2 Fredrickson BE, Baker D, McHolick WJ, et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:699-707.

This study provides insight to the natural history of the long-term patient with spondylolisthesis.

3 Gaines R, Nichols W. Treatment of spondyloptosis by two-stage L5 vertebrectomy and reduction of L4 onto S1. Spine. 1985;10:680-686.

4 Schlenzka D, Remes V, Helenius I, et al. Direct repair for treatment of symptomatic spondylolisthesis in young patients: no benefit in comparison to segmental fusion after a mean follow-up of 14.8 years. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1437-1447.

5 Swan J, Hurwitz E, Malek F, et al. Surgical treatment for unstable low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults: a prospective controlled study of posterior instrumented fusion compared with combined anterior-posterior fusion. Spine J. 2006;6:606-614.

6 Spruit M, van Jonbergen JP, deKleuver M. A concise follow-up of a previous report: Posterior reduction and anterior lumbar interbody fusion in symptomatic low-grade adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:828-832.

1 Wiltse LL. Spondylolisthesis: Classification and etiology. Symposium on the Spine. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1969. 143-168

2 Wiltse LL, Newman PH, McNab I. Classification of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:23-29.

3 Wiltse LL, Winter RB. Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65A:768-772.

4 Rosenberg NJ. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: surgical treatment. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:112-120.

5 Rowe GG, Roche MB. The etiology of separate neural arch. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35A:102-109.

6 Iguchi T, Wakami T, Kurihara A, et al. Lumbar multilevel degenerative spondylolisthesis: radiological evaluation and factors related to anterolisthesis and retrolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:93-99.

7 Fredrickson BE, Baker D, McHolick WJ, et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:699-707.

8 Meyerding H. Spondylolisthesis: surgical treatments and results. Surg Gyn Obstet. 1932;54:371-377.

9 Boxall D, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al. Management of severe spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:479-495.

10 Taillard W. Etiology of spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:30-39.

11 Stewart TD. The age incidence of neural arch defects in Alaskan natives, considered from the standpoint of etiology. J Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35A:937.

12 Wynne-Davies R, Scott JHS. Inheritance and spondylolisthesis: a radiographic family survey. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61B:301-305.

13 Wiltse LL, Rothman SLG. Spondylolisthesis: classification, diagnosis, and natural history. Semin Spine Surg. 1989;1:78.

14 Wiltse LL, Widell EH, Jackson DW. Fatigue fracture: the basic lesion in isthmic spondylisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:17-22.

15 Don AS, Robertson PA. Facet joint orientation in spondylolysis and isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:112-115.

16 Vaccaro AR, Martyak GC, Madigan L. Adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Orthopedics. 2001;12:1172-1177.

17 Bunnell WP. Back pain in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;13:587-604.

18 Turner RH, Bianco AJJr. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and teenagers. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53A:1298-1306.

19 Bell DF, Erlich MG, Zaleske DJ. Brace treatment of symptomatic spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1988;236:192.

20 Wiltse LL. Spondylolisthesis and its treatment. In: Finneson BE, editor. Low Back Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1980:451-493.

21 Sijbrandij S. Reduction and stabilization of severe spondylolisthesis: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1983;56B:40-42.

22 Steffe AD, Sitkowski DJ. Reduction and stabilization of grade IV spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1988;227:82-89.

23 Vercanteren M, DeGroote W, Van Nuffel J, et al. Reduction of spondylolisthesis with severe slipping. Acta Orthop Belg. 1981;47:502-511.

24 Edwards CC. Prospective evaluation of a new method for complete reduction of L5-S1 spondylolisthesis using corrective forces alone. Orthop Trans. 1990;14:549.

25 Gaines R, Nichols W. Treatment of spondyloptosis by two-stage L5 vertebrectomy and reduction of L4 onto S1. Spine. 1985;10:680-686.

26 Boachie-Adjei O, Do T, Rawlins BA. Partial lumbosacral kyphosis reduction, decompression, and posterior lumbosacral transfixation in high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis: clinical and radiographic results in six patients. Spine. 2002;27:E161-E168.

27 Brown CW, Orme TJ, Richardson HD. The rate of pseudoarthrosis (surgical non union) in patients who are smokers and patients who are non-smokers: a comparison study. Spine. 1986;11:942-943.

28 McGuire RA, Amundson GM. The use of primary internal fixation in spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;15:1662-1672.

29 Vaccaro A, Ring D, Scuderi G, et al. Predictors of outcome in patients with chronic back pain and low-grade spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1997;22:2030-2035.

30 Schlenzka D, Seitsalo S, Poussa M, et al. Operative treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and mild spondylolisthesis in young patients: direct repair of the defect or segmental spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 1993;2:104-112.

31 Hambly M, Lee CK, Gutteling E, et al. Tension band wiring-bone grafting for spondylolysis and spondylolisthsis: a clinical and biomechanical study. Spine. 1989;14:455-460.

32 Buck J. Direct repair of the defect in spondylolisthesis: preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1970;52B:432-437.

33 Buck J. Further thoughts on direct repair of the defect in spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61B:123.

34 Osterman K, Lindholm TS, Laurent LE. Late results of removal of the loose posterior element (Gill’s operation) in the treatment of lytic lumbar spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:121-128.

35 Gill GG, Manning JG, White HL. Surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis without spine fusion. J Bone Joint Surg. 1955;37:493-520.

36 Gill GG. Long-term follow-up evaluation of a few patients with spondylolisthesis treated by excision of the loose lamina with decompression of the nerve roots without spinal fusion. Clin Orthop. 1984;182:215-219.

37 Van Rens JG, Van Horn JR. Long-term results in lumbosacral interbody fusion for spondylolisthesis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53:383-392.

38 Ekman P, Moller H, Hedlund R. The long-term effect of posterolateral fusion in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis: a randomized controlled study. Spine J. 2005;5:36-44.

39 Deguchi M, Rapoff A, Zdeblick TA. Posterolateral fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults: analysis of fusion rate and clinical results. J Spinal Dis. 1998;11:459-464.

40 Watkins MB. Posterolateral bone-grafting for fusion of the lumbar and lumbosacral spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;41A:388-396.

41 Carragee E. Single-level posterolateral arthrodesis, with or without posterior decompression, for the treatment of isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg AM. 1997;79:1175-1180.

42 Kim NH, Lee JW. Anterior interbody fusion versus posterolateral fusion with transpedicular fixation for isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. A comparison of clinical results. Spine. 1999;24:812-817.

43 McPhee IB, O’Brien JP. Reduction of severe spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1979;4:430-434.

44 Csecsei GI, Klekner AP, Dobai J, et al. Posterior interbody fusion using laminectomy bone and transpedicular screw fixation in the treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:2-6. discussion 6-7

45 Curylo LJ, Edwards C, DeWald RW. Radiographic markers in spondyloptosis, implications for spondylolisthesis progression. Spine. 2002;27:2021-2025.

46 Kawakami M, Tamaki T, Ando M, et al. Lumbar sagittal balance influences the clinical outcome after decompression and posterolateral spinal fusion for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2002;27:59-64.

47 Huang RP, Bohlman HH, Thompson GH, et al. Predictive value of pelvic incidence in progression of spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2003;28:2381-2385.

48 Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, et al. Spondylolisthesis, pelvic incidence, and spinopelvic balance: a correlation study. Spine. 2004;29:2049-2054. 15

49 Hanson DS, Bridwell KH, Rhee JM, et al. Correlation of pelvic incidence with low-and high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2002;27:2026-2029.

50 Bradford D, Iza J. Repair of the defect in spondylolysis or minimal degrees of spondylolisthesis by segmental wire fixation and bone grafting. Spine. 1985;10:673-679.

51 Morelos O, Pozzo AO. Selective instrumentation, reduction and repair in low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Int Orthop. 2004;28:180-182.

52 Schlenzka D, Remes V, Helenius I, et al. Direct repair for treatment of symptomatic spondylolisthesis in young patients: no benefit in comparison to segmental fusion after a mean follow-up of 14.8 years. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1437-1447.

53 Seitsalo S, Schlenska D, Poussa M, et al. Disc degeneration in young patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis treated operatively or conservatively: a long-term follow-up. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:393-397.

54 Hambly MF, Wiltse LL, Raghavan N, et al. The transition zone above a lumbosacral fusion. Spine. 1998;23:1785-1792. 15

55 Swan J, Hurwitz E, Malek F, et al. Surgical treatment for unstable low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults: a prospective controlled study of posterior instrumented fusion compared with combined anterior-posterior fusion. Spine J. 2006;6:606-614.

56 Moller H, Hedlund R. Instrumented and noninstrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis—a prospective randomized study: part 2. Spine. 2000;5:1716-1721.

57 Potter BK, Freedman BA, Verwiebe EG, et al. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: clinical and radiographic results and complications in 100 consecutive patients. J Spinal Discord Tech. 2005;18:337-346.

58 Ishihara H, Osada R, Kanamori M, et al. Minimum 10-year follow-up study of anterior lumbar interbody fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:91-99.

59 La Rosa G, Conti A, Cacciola F, et al. Pedical screw fixation for isthmic spondylolisthesis: does posterior lumbar interbody fusion improve outcome over posterolateral fusion? Neurosurg. 2003;99(2 Suppl):143-150.

60 Spruit M, van Jonbergen JP, deKleuver M. A concise follow-up of a previous report: Posterior reduction and anterior lumbar interbody fusion in symptomatic low-grade adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:828-832.

61 Molinari RW, Sloboda JF, Arrington EC. Low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis treated with instrumented posterior lumbar interbody fusion in U.S. servicemen. J Spinal Disorder Tech. 2005;18(Suppl):S24-S29.

62 Sasso RC, Shively KD, Reilly TM. Transvertebral transsacral strut grafting for high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis L5-S1 with fibular allograft. J Spinal Discord Tech. 2008;21:328-333.

63 Transfeldt EE, Mehbod AA. Evidence-based medicine analysis of isthmic spondylolisthesis treatment including reduction versus fusion in situ for high-grade slips. Spine. 2007;32(19 Suppl):S126-S129.