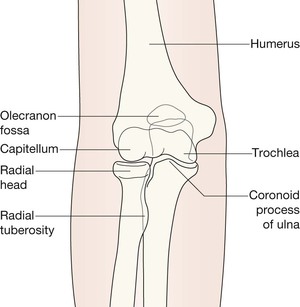

Adult elbow

AP view 116

Lateral view 116

Elbow fat pads 117

Analysis: three questions to answer

Are the fat pads normal on the lateral view? 118

Is the cortex of the radial head and neck smooth on both views? 119

Is the radiocapitellar line normal? 120

Fracture of the head or neck of the radius 121

Normal variants 124

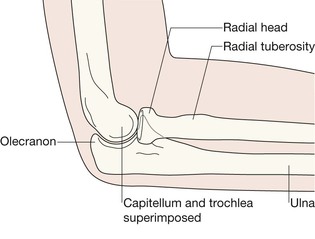

Lateral view

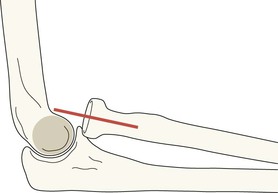

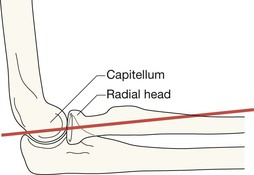

On the lateral view: the line to draw is along the long axis of the proximal 2–3 cm of the shaft of the radius. This line should pass through the capitellum.Radiocapitellar line

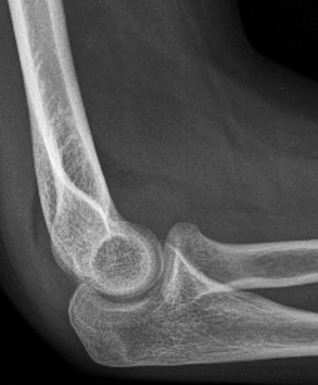

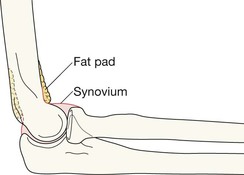

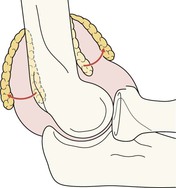

Elbow fat pads

Two pads of fat are situated close to the cortex of the distal humerus. Referred to as the anterior and posterior fat pads, these are external to the synovial lining of the joint. The fat pads are never visualised on the AP projection. Look for them on the lateral view. The fat is seen as a dark streak in the surrounding grey soft tissues.

▪ The anterior fat pad will be seen in most (but not all) normal elbows and is closely applied to the humerus.

▪ The posterior fat pad is not visible on the radiograph of a normal elbow because it is situated deep within the olecranon fossa. Because the elbow is radiographed in the flexed position this fat shadow is hidden by the overlying bone.

If the AP and lateral radiographs appear normal it is important that the images are again checked in a methodical manner. Ask yourself three questions. The same principles apply as for the paediatric elbow (p. 102). Recap:Analysis: three questions to answer

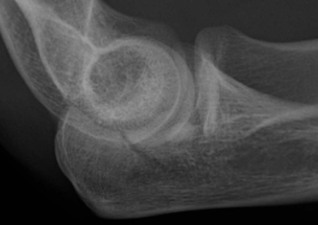

Question 1—Are the fat pads normal on the lateral view?

The black stripe against the anterior cortex of the humerus is a normally positioned anterior fat pad. Normal elbow.

The anterior fat pad is lifted off the bone (“the sail sign”) indicating an effusion. This is a variation of the standard lateral view (angled as described on p. 121). The fracture involving the head and neck of the radius is well shown.

Displaced anterior and posterior fat pads. Fracture head of radius (irregularity of the anterior cortex).

Large effusion shown by the gross displacement of the anterior and posterior fat pads. No obvious fracture on this radiograph. The AP will need careful scrutiny—particularly, the appearance of the head of the radius.

Displaced fat pads. The head of the radius shows a slight crinkle in the cortex: undisplaced fracture.

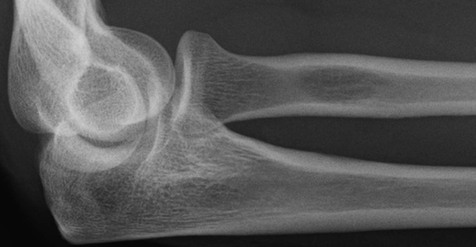

Radial head and neck. Normal cortices. No step, no crinkle, no angulation.

Fracture involving the head and neck of the radius. An intra-articular fracture line and a step in the lateral cortex.

Fracture involving the head and neck of the radius. Subtle break in the articular cortex.

Fracture neck of radius. Subtle fracture line in the lateral cortex.

Question 3—Is the radiocapitellar (RC) line normal?4

In the adult, these fractures represent 50% of all fractures at the elbow. An additional radiograph. Some Emergency Departments routinely add a third (an angled) projection to the standard AP and lateral views. This is termed the radial head-capitellum view3. The patient is positioned as for the lateral view but the tube is angled 45° to the joint. This is an excellent projection for evaluation of the radial head.The common injuries

Fracture of the head or neck of the radius

Angled projection. Fracture of radial head and neck.

Fracture through the radial neck.

Slight kink indicates a fracture of the radial neck.

Fracture of the radial head and neck.

Accounts for 10-20% of adult elbow fractures.Fracture of the olecranon5

Undisplaced fracture involving the olecranon.

Displaced fracture of the olecranon.

Comminuted fracture of the olecranon.

The major fragment is widely displaced posteriorly.

This combination injury represents less than 5% of all elbow fractures or dislocations4–6. Often referred to as a Monteggia fracture–dislocation or a Monteggia lesion. It comprises a fracture of the ulna and dislocation of the head of the radius. Background: the forearm bones can be regarded as acting as a single functional unit as they are bound together by the strong interosseous membrane and ligaments. Consequently, a displaced or angulated fracture of just one of these two bones will be accompanied by an injury affecting the other bone—invariably a dislocation. Whenever there is a displaced fracture of the ulna, but an intact radius it is important to assess the proximal radio-ulnar joint for a dislocation of the head of the radius utilising the radiocapitellar line. This assessment will show whether a Monteggia injury is present. Clinical impact guideline: early diagnosis is clinically very important… “the key to a good result following a Monteggia fracture–dislocation is prompt recognition of the injury pattern”2.A rare but important injury

The Monteggia injury1,2,5

Monteggia injury. Comminuted, displaced, and angulated fracture of the ulna. Intact radius. Abnormal radiocapitellar line reveals a dislocation of the head of the radius. This injury follows the principle of the Two Bone Rule (p. 146).

An angled projection (see p. 121) showing normal alignment of the head of the radius with the capitellum. The radiocapitellar line (p. 117) is unquestionably normal.

Pitfalls

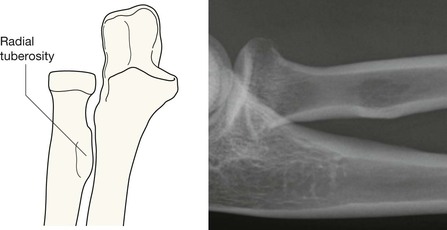

A common normal variant. The tuberosity of the radius can cause a difficulty. The tendon of the biceps muscle is attached to this tuberosity. On the lateral view the normal tuberosity may be seen en face and, because of the relative density of the margins of the tuberosity, it can appear as an oval lucency. This lucency may be mistaken for an area of bone destruction or a bone cyst6. The apparent “cyst” in the shaft of this radius is entirely normal. Another example is evident on p. 123.

An occasional normal variant. This upper arm was lacerated by a glass bottle. The lateral radiograph showed this density anterior to the shaft of the humerus above the elbow. This is not a glass fragment. It is an atavistic supracondylar spur.

A supracondylar spur occurs in 1–2% of normal individuals. It is a normal structure in some mammals, particularly climbing animals7. In clinical practice it is usually an incidental and unimportant finding. Occasionally a spur may cause symptoms usually related to its effect on the median or ulnar nerve.