Chapter 45

Adult Congenital Heart Disease

1. Which patients with adult congenital heart disease require antibiotic prophylaxis?

Unrepaired cyanotic heart disease

Unrepaired cyanotic heart disease

Residual defects after repair with prosthetic material

Residual defects after repair with prosthetic material

The new guidelines have also eliminated indications for prophylaxis for genitourinary (GU) or gastrointestinal (GI) procedures. (See also Chapter 33 on endocarditis and endocarditis prophylaxis).

2. What are the three main types of atrial septal defects (ASDs), and what are their associated anomalies?

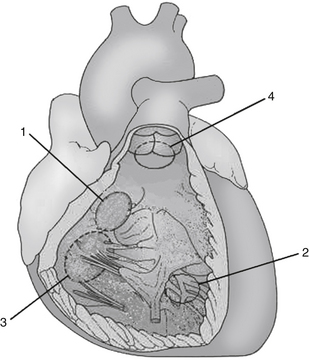

The three main types of ASDs are secundum (70%), primum (20%), and sinus venosus (10%). The secundum ASD is a defect involving the floor of the fossa ovalis of the atrial septum. It usually presents as an isolated anomaly. The primum ASD is a defect at the base of the atrial septum adjacent to the atrioventricular valves. It is invariably part of an atrioventricular septal defect (endocardial cushion defect), and a cleft mitral valve is almost always present. The sinus venosus ASD is a defect of the posterior part of the septum, usually located in the superior part. In the majority of cases, a sinus venosus ASD is associated with anomalous connections or drainage of the right-sided pulmonary veins (Fig. 45-1).

Figure 45-1 Atrial septal defects: 1, secundum; 2, primum; 3, sinus venosus. (Modified from Gatzoulis MA, Webb GD, Daubeney PEF, et al: Diagnosis and management of adult congenital heart disease, Edinburgh, 2003, Churchill Livingstone, p 163.) CS, Coronary sinus; EV, eustachian valve; SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava.

3. When should an ASD be closed? Which ASDs cannot be closed by a percutaneous device?

4. List the four types of ventricular septal defects (VSDs).

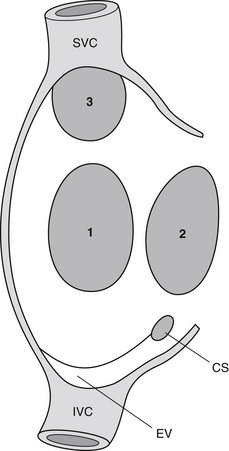

Different classifications for VSDs have been used; one common approach divides VSDs into four types:

Membranous or perimembranous VSDs involve the membranous ventricular septum, a small localized area of the normal ventricular septum that is fibrous. This is the most common type of VSD seen in the adult.

Membranous or perimembranous VSDs involve the membranous ventricular septum, a small localized area of the normal ventricular septum that is fibrous. This is the most common type of VSD seen in the adult.

Muscular VSDs involve the trabecular portion of the septum.

Muscular VSDs involve the trabecular portion of the septum.

Inlet VSDs involve the part of the ventricular septum that is adjacent to the tricuspid and mitral valves. Inlet VSDs are always associated with atrioventricular septal defects.

Inlet VSDs involve the part of the ventricular septum that is adjacent to the tricuspid and mitral valves. Inlet VSDs are always associated with atrioventricular septal defects.

Outlet VSDs (also known as supracristal VSD) involves the portion of the ventricular septum that is just below the aortic and pulmonary valve (Fig. 45-2).

Outlet VSDs (also known as supracristal VSD) involves the portion of the ventricular septum that is just below the aortic and pulmonary valve (Fig. 45-2).

5. What are the long-term complications of a small VSD in the adult patient?

6. What are the complications of a bicuspid aortic valve?

A bicuspid aortic valve is present in 0.5% to 1% of the population. The main complications are progressive aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, or a combination of both. Other complications include endocarditis and aortopathy. Although infrequent (<10%), aortic coarctation is also a well-described association and must be ruled out in these patients. Patients in whom the bicuspid valve demonstrates signs of valve degeneration on echocardiography are at an increased risk of cardiovascular events and need close regular follow-up.

7. How is hemodynamic severity of coarctation of the aorta assessed in the adult patient?

8. In coarctation of the aorta in the adult patient, when should percutaneous stenting be considered?

Most clinicians think that adult patients with hemodynamically significant coarctation of the aorta should be considered for intervention. Although surgery has been available for several decades, percutaneous dilation with stenting has evolved as an alternative. In the adult patient with residual stenosis after repair, stenting has become the first-line therapy at most centers. For adults with native coarctation, stenting has also become first-line therapy at many centers. In patients who undergo percutaneous stenting, the anatomy needs to be suitable (i.e., no significant arch hypoplasia). In adult patients who undergo surgery, the usual procedure is placement of an interposition graft which is done through a left-sided thoracotomy approach.

9. Which adult patients with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) require percutaneous device closure?

10. How is Marfan syndrome diagnosed?

11. When should Marfan patients with aortic root dilation be referred for surgery?

12. What is tetralogy of Fallot, and what is the main complication seen in the adult?

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) consists of four features: right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction, a large VSD, an overriding ascending aorta, and right ventricular hypertrophy. The RVOT obstruction is the clinically important lesion and may be subvalvular, valvular, or supravalvular, or may be at multiple levels. Repair, done in infancy, involves closing the VSD and relieving the RVOT obstruction. In many patients, to relieve the RVOT obstruction, surgery on the pulmonary annulus and valve leaflets is required and is usually complicated by severe residual pulmonary insufficiency. In the adult, over time, chronic severe pulmonary insufficiency often leads to right ventricular dysfunction and exercise intolerance, for which a pulmonary valve replacement (PVR) may be necessary. When PVR is performed, a tissue prosthesis is usually placed (homograft, porcine, or bovine prosthesis). The problem with tissue prostheses in young adults is that they require replacement at 10- to 15-year intervals. A percutaneous pulmonary valve prosthesis approach is increasingly being used to manage these patients with severe pulmonary insufficiency. Other complications in TOF include residual RVOT obstruction, residual VSD leak, right ventricular dysfunction, aortic root dilation, and arrhythmias.

13. What are the three Ds of Ebstein anomaly?

14. What drug therapy should now be considered in all patients with Eisenmenger syndrome?

15. When should an Eisenmenger patient be phlebotomized?

In patients with symptoms of hyperviscosity (headaches, dizziness, fatigue, achiness), who have a hematocrit more than 65% with no evidence of iron deficiency

In patients with symptoms of hyperviscosity (headaches, dizziness, fatigue, achiness), who have a hematocrit more than 65% with no evidence of iron deficiency

Preoperatively, to improve hemostasis (goal hematocrit less than 65%)

Preoperatively, to improve hemostasis (goal hematocrit less than 65%)

In modern practice, only a minority of Eisenmenger patients should undergo phlebotomy.

16. Which types of congenital heart disease lesions have particularly poor outcomes in pregnancy?

Very high risk congenital heart disease lesions include the following:

Unrepaired cyanotic heart disease

Unrepaired cyanotic heart disease

Marfan syndrome with a dilated aortic root (greater than 40 mm)

Marfan syndrome with a dilated aortic root (greater than 40 mm)

Significant systemic ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction 40% or less).

Significant systemic ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction 40% or less).

These patients should be counseled accordingly about the significant maternal risks and poor fetal outcomes that are associated with pregnancy.

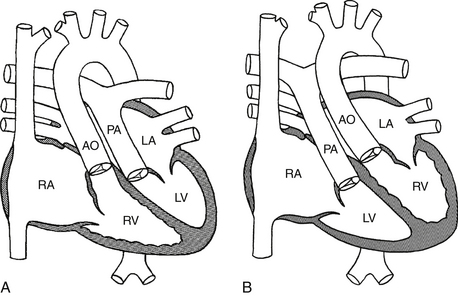

17. What are the two types of transpositions?

Transposition complexes can be divided into two groups. In complete transposition of the great arteries (dextro- or D-TGA), the anomaly can be simplistically conceptualized as an inversion of the great vessels (Fig. 45-3, A). The aorta comes out of the right ventricle, and the pulmonary artery comes out of the left ventricle. Desaturated blood is pumped into the systemic circulation, whereas oxygenated blood is pumped into the pulmonary circulation. Without intervention, this condition is associated with very poor outcomes in early infancy.

Figure 45-3 A, D-TGA. B, L-TGA. (Modified from Mullins CE, Mayer DC: Congenital heart disease, a diagrammatic atlas, New York, 1988, Wiley-Liss, pp 164, 182.) AO, Aorta; D-TGA, dextro-transposition of the great arteries; L-TGA, levo-transposition of the great arteries; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (levo- or L-TGA) can be conceptualized as an inversion of the ventricles (see Fig. 45-3, B). Desaturated blood and oxygenated blood are thus pumped in the appropriate arterial circulations. In many cases, associated anomalies, such as a VSD, pulmonary stenosis, an abnormal tricuspid valve, and heart block, are present. These patients can survive or present de novo in adulthood without surgical intervention.

18. What is meant by a systemic right ventricle?

A systemic right ventricle refers to a heart anomaly where the morphologic right ventricle pumps blood into the aorta. Ventricular morphology is determined by anatomic features typical to each ventricle. For example, the morphologic right ventricle has a tricuspid atrioventricular valve (with attachments to the septum and apical displacement compared with the mitral valve) and coarse apical trabeculations. L-TGA (see Question 17) is a congenital heart defect in which there is a systemic right ventricle. In the first few decades of life, the right ventricle is able to handle pumping into the high-pressure systemic circulation; however, in adulthood, the right ventricular function begins to deteriorate in the majority of patients. This is usually associated with tricuspid regurgitation and manifests clinically as heart failure.

19. What is the difference between an atrial and an arterial switch?

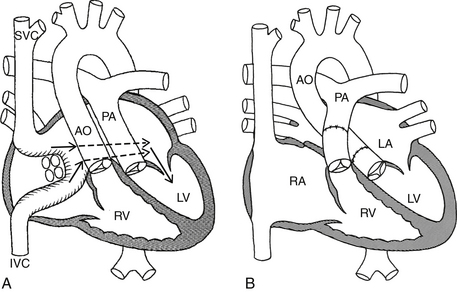

An atrial switch is a surgical procedure that was previously done for patients born with D-TGA (Fig. 45-4, A). The Mustard and Senning procedures are both examples of an atrial switch and involve rerouting systemic and pulmonary venous flow to the respective pulmonary and systemic ventricles. These procedures were replaced by the arterial switch, which consists of “switching” the great arteries and reimplanting the coronary arteries to the new aorta (see Fig. 45-4, B). The arterial switch is performed in the first few weeks after birth and has been the standard of care for patients born with D-TGA for more than two decades.

Figure 45-4 A, Atrial switch for D-TGA (Mustard or Senning procedure). The arrows show how a baffle shunts blood from the superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC) into the left ventricle (LV). Oxygenated blood from the pulmonary veins is shunted in to the right ventricle (RV). B, Arterial switch for D-TGA. The aorta (AO) and pulmonary artery (PA) are surgically “switched.” (Modified from Mullins CE, Mayer DC: Congenital heart disease, a diagrammatic atlas, New York, 1988, Wiley-Liss, pp. 296, 300.) D-TGA, Dextro-transposition of the great arteries; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Baumgartner, H., Bonhoeffer, P., De Groot, N.M., et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2915–2957.

2. Canadian Adult Congenital Heart Network. The CACH Network website. Available at http://www.cachnet.org. Accessed February 27, 2013

3. Galiè, N., Beghetti, M., Gatzoulis, M.A., et al. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger Syndrome. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 2006;114:48–54.

4. Gatzoulis, M.A., Webb, G.D., Daubeney, P.E.F. Diagnosis and management of adult congenital heart disease, ed 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

5. Maron, B.J., Zipes, D.P., Ackerman, M.J., et al. Bethesda Conference report: 36th Bethesda Conference. Eligibility recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1312–1375.

6. National Marfan Foundation. The NFM website. Available at http://www.marfan.org. Accessed February 27, 2013

7. Nevil Thomas Adult Congenital Heart Library. The Nevil Thomas Adult Congenital Heart Library website. Available at http://www.achd-library.com. Accessed February 27, 2013

8. Silversides, C.K., Marelli, A., Beauchesne, L., et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:143–150.

9. Warnes, C.A., Williams, R.G., Bashore, T.M., et al. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:e143–e263.