Adrenalectomy

ANATOMY

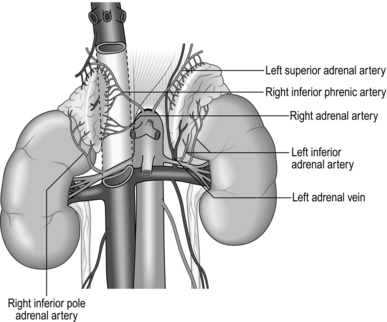

The normal adrenal gland weighs 3–5 g and measures 5x3x1 cm. Both left and right glands lie in the retroperitoneum within the perirenal (Gerota’s) fascia, with their posterior surface attached to the diaphragm. They receive arterial blood supply from several small branches of the inferior phrenic artery, aorta and renal artery. The adrenals are not symmetrical: the right is triangular in shape and its short, wide adrenal vein drains medially into the inferior vena cava; the left is more semilunar, with the vein draining downwards into the left renal vein. Each adrenal gland consists of medulla, secreting catecholamines (adrenaline (epinephrine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and dopamine), and cortex, secreting cortisol, aldosterone and adrenal sex hormones (Fig. 22.1). Lymphatic capillaries draining the cortex follow arteries while the medulla lymphatics follow veins.

Appraise

Before you embark on adrenalectomy, consider:

1. The functional status of the adrenal nodule, as this determines patient preparation before surgery and perioperative management.

2. Look at the size of the adrenal mass and its relation to surrounding organs. This determines your choice of incision and approach. You must review CT or MRI scans yourself and have them available in the operating theatre during surgery.

3. Decide whether you are dealing with malignant or benign pathology.

4. Find out whether this is a sporadic or familial problem.

5. Ensure that surgery is the best treatment and is really necessary.

Indications for adrenalectomy

1. Phaeochromocytomas arise from adrenal medulla and secrete adrenaline (epinephrine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and dopamine. It is difficult to predict their biological behaviour but 10% of them are malignant and 10% arise from chromaffin cells outside the adrenals (paragangliomas). Most of them are sporadic, but 20–30% are familial and may be bilateral. Patients present with headaches, sweating, hypertension and palpitations. Establish the biochemical diagnosis by measuring catecholamine and metanephrine levels in urine and plasma. CT, MRI and MIBG (meta-iodobenzyl-guanidine) scans are used to assess tumour location and size and to detect possible metastases. Carefully prepare all patients with phaeochromocytomas with α blockade and sometimes β blockade to minimize the risk of hypertensive crisis. During surgery avoid extensive manipulation of the tumour to prevent a sudden rise in blood pressure. You should work with an experienced anaesthetist who is able to control surges of blood pressure during dissection and hypotension after the removal of the tumour.

2. Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome) is caused by excess of aldosterone produced by either a solitary adenoma or bilateral hyperplasia of the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex. Patients present with hypertension and low potassium. Biochemical diagnosis is confirmed by an elevated plasma aldosterone concentration and suppressed plasma renin activity. Use CT or MRI scans to identify adrenal nodules, which are usually about 1 cm in size. Adrenal venous sampling is sometimes necessary to differentiate unilateral from bilateral disease. The aim of the treatment is to normalize aldosterone levels and prevent mortality and morbidity caused by hypertension, low potassium, cardiovascular and renal damage. Unilateral adenomas should be treated with adrenalectomy, which corrects hypokalaemia in 98% and improves hypertension in 90% of patients. Patients with bilateral hyperplasia should be treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (e.g. spironolactone), not surgery.

3. Hypercorticolism is caused by excess of cortisol. Cushing’s disease is caused by pituitary ACTH producing adenomas, which stimulates adrenal production of cortisol. Twenty-five percent of patients are not cured by transphenoidal pituitary surgery and require bilateral adrenalectomy. Cushing’s syndrome is caused by a cortisol-secreting adenoma or rarely adrenocortical carcinoma and is an indication for unilateral adrenalectomy. Patients present with central obesity, hypertension, diabetes and muscle weakness. They have impaired immunity and poor wound healing. Biochemical diagnosis is made by measuring plasma ACTH and urine cortisol and performing a dexamethasone suppression test. Before surgery hypercorticolism can be controlled with ketaconazole or metyrapone. After bilateral adrenalectomy patients need lifelong treatment with hydrocortisone and mineralocorticoids. The contralateral gland is often suppressed after unilateral adrenalectomy and these patients also need treatment with hydrocortisone for many months.

4. Adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare but highly malignant tumour with poor prognosis. 60% of adrenal cancers are hormonally active and can cause Cushing’s or virilizing syndromes. Most of these tumours are large at diagnosis and an open approach should be used to resect them. Surgery often needs to be extensive with en bloc removal of adrenal and surrounding organs combined with lymphadenopathy. Tumour spillage must be avoided at all cost to prevent local recurrence.

5. Adrenal ‘incidentaloma’ is a mass discovered by chance during radiological investigations performed for other indications. They are common, with a prevalence of 4–6%. Most of them (70%) are non-secreting adenomas, but about 16% are hyperfunctioning and cause subclinical Cushing’s, Conn’s or phaeochromocytoma syndromes. Incidentalomas larger than 4–5 cm may represent malignant pathology. Hyperfunctioning and large incidentalomas suspicious of being malignant should be resected.

Prepare

1. With the correct diagnosis established and the perioperative plan discussed with an endocrinologist and implemented, you can now plan your surgical procedure. Depending on pathology you must make a decision:

Whether to perform unilateral or bilateral adrenalectomy

Whether to perform unilateral or bilateral adrenalectomy

2. Order perioperative thromboprophylaxis. If MRSA screening is positive use the hospital eradication protocol. Consider giving prophylactic antibiotics – important in Cushing’s syndrome.

3. Discuss these decisions fully with the patient while taking a full formal consent.

Access

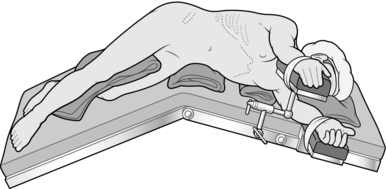

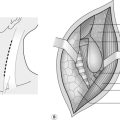

Lateral approach (Fig. 22.2)

Laparoscopic lateral (transperitoneal) approach

1. Tilt the operating table laterally to a position half way between true lateral and fully supine and stand facing the patient’s abdomen with your camera operator next to you and scrub nurse opposite.

2. Create a pneumoperitoneum using an open technique (recommended) or Veress needle to achieve a pressure between 10 and 15 mmHg.

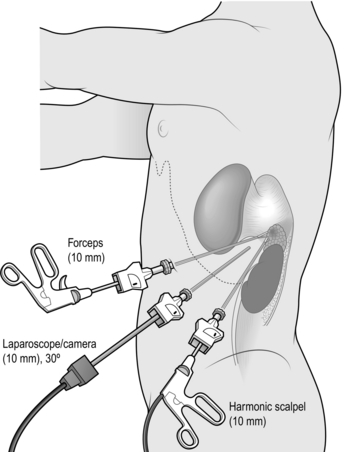

3. Insert the first port below the costal margin in the mid-clavicular line and inspect the peritoneal cavity with a 0° or 30° telescope. Insert two or three further ports in the posterior, middle and anterior axillary lines (Fig. 22.3). Use a combination of 5- and 10–12-mm ports, depending on which instruments you are planning to use (e.g. 10 mm for camera, 12 mm for vascular stapler, 5 mm for forceps/diathermy/harmonic scalpel).

4. Left adrenalectomy (Fig. 22.3) is usually performed with three ports but a fourth port may be necessary for additional retraction of the spleen and colon:

Mobilize the splenic flexure by dividing its lateral and superior attachments until you see the upper half of the kidney and lower edge of spleen.

Mobilize the splenic flexure by dividing its lateral and superior attachments until you see the upper half of the kidney and lower edge of spleen.

Mobilize the spleen and tail of pancreas by dividing splenocolic and splenorenal ligaments until, assisted by gentle traction and forces of gravity, they ‘flip’ medially. Ensure good access to the adrenal to secure a trouble-free operation and dissect thoroughly and, if necessary, extensively. Be aware of the spleen, colon, pancreas and splenic vein in order to avoid damaging them.

Mobilize the spleen and tail of pancreas by dividing splenocolic and splenorenal ligaments until, assisted by gentle traction and forces of gravity, they ‘flip’ medially. Ensure good access to the adrenal to secure a trouble-free operation and dissect thoroughly and, if necessary, extensively. Be aware of the spleen, colon, pancreas and splenic vein in order to avoid damaging them.

Identify the adrenal in the perirenal fat and start dissecting it at the upper pole; carry the dissection downwards along both medial and lateral borders. Divide small arterial branches with a harmonic scalpel. Make sure that whole gland is mobilized – the lower limb frequently descends as far as the renal hilum. Do not grasp the adrenal with forceps as it is friable and bleeds easily. Retract by pushing the adrenal or apply forceps to the surrounding fat.

Identify the adrenal in the perirenal fat and start dissecting it at the upper pole; carry the dissection downwards along both medial and lateral borders. Divide small arterial branches with a harmonic scalpel. Make sure that whole gland is mobilized – the lower limb frequently descends as far as the renal hilum. Do not grasp the adrenal with forceps as it is friable and bleeds easily. Retract by pushing the adrenal or apply forceps to the surrounding fat.

Identify the left adrenal vein on the inferomedial aspect of the gland as it empties into the renal vein. Divide it between double clips. Be careful not to damage the renal vessels, which may contribute an accessory renal artery to the superior pole.

Identify the left adrenal vein on the inferomedial aspect of the gland as it empties into the renal vein. Divide it between double clips. Be careful not to damage the renal vessels, which may contribute an accessory renal artery to the superior pole.

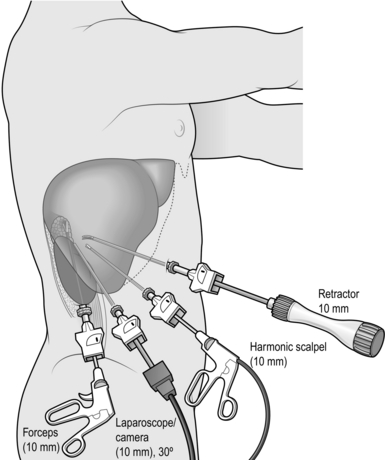

5. Right adrenalectomy (Fig. 22.4) is usually performed through four ports as it is necessary to retract the right lobe of the liver:

The duodenum and hepatic flexure of the colon do not need to be mobilized routinely as they are retracted by forces of gravity.

The duodenum and hepatic flexure of the colon do not need to be mobilized routinely as they are retracted by forces of gravity.

Divide the right triangular ligament and retract the liver medially. Incise the posterior peritoneum along the lateral edge of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and lower edge of the liver and identify the adrenal gland.

Divide the right triangular ligament and retract the liver medially. Incise the posterior peritoneum along the lateral edge of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and lower edge of the liver and identify the adrenal gland.

Gently dissect between the IVC and adrenal until you encounter the right adrenal vein. For larger tumours it may be helpful to dissect the lower and lateral aspects of the adrenal first as this helps to retract it and facilitates dissection between the medial edge and IVC.

Gently dissect between the IVC and adrenal until you encounter the right adrenal vein. For larger tumours it may be helpful to dissect the lower and lateral aspects of the adrenal first as this helps to retract it and facilitates dissection between the medial edge and IVC.

The right adrenal vein is short and wide. Divide it between double clips or using a vascular stapler. Mobilize the remaining gland from the kidney, liver and posterior muscles by dividing small arteries with a harmonic scalpel.

The right adrenal vein is short and wide. Divide it between double clips or using a vascular stapler. Mobilize the remaining gland from the kidney, liver and posterior muscles by dividing small arteries with a harmonic scalpel.

6. After completely mobilizing the right or left adrenal, place it in a retrieval bag and retrieve it through one of the incisions.

7. Check haemostasis, make sure there is no damage to surrounding organs and close the incisions with stitches.

Open posterolateral approach

1. The technique for left and right adrenalectomy is similar.

2. Make an incision over the eleventh rib from the lateral edge of the paravertabral muscles to the lateral rectus sheath margin. Divide latissimus dorsi and serratus posterior muscles with cutting diathermy and incise the periosteum of the eleventh rib using a diathermy point. Strip the periosteum from the rib throughout its length, freeing the deep attachments to the rib with a gauze swab. Dissect the rib free anteriorly first, elevating it as the dissection proceeds.

3. Cut through the costal cartilage with scissors and remove it. Sweep the pleura superiorly and posteriorly and similarly sweep the peritoneum anteriorly, using gauze swabs.

4. Identify the kidney lying inferiorly. Incise the deep fascia, allowing the retroperitoneal fat to bulge out. Have your assistant retract the kidney inferiorly while you proceed carefully to bluntly dissect the fat above and medial to the kidney.

5. Identify and mobilize right or left adrenal gland as described above, paying attention to haemostasis. Handle the gland gently to avoid disruption and avoid damaging surrounding organs.

6. Close the wound in layers. Take care to close the pleura if it was opened, after asking the anaesthetist to expand the lungs. Drains are not usually necessary. As a rule, order a chest X-ray in the recovery ward to exclude a significant pneumothorax.

Posterior (retroperitoneal) approach

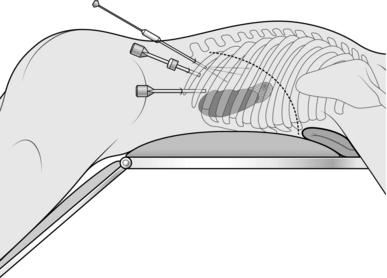

Endoscopic posterior (retroperitoneal) approach (Fig. 22.5)

Fig. 22.5 Position on the operating table and placement of trocars post posterior endoscopic adrenalectomy.

1. The technique for left and right adrenalectomy is similar.

2. Make an incision between the tips of the eleventh and twelfth ribs and dissect bluntly through the muscles until you can feel the kidney. Insert the first port and create an artificial space using either an inflatable balloon or blunt dissection aided by CO2 insufflation at a pressure of around 20 mmHg.

3. Introduce two further ports (5 mm) close to the costal margins on either side of the port used for the 0° or 30° camera.

4. Carry the dissection close to the quadrate lumbar muscle to avoid opening peritoneum. Identify the kidney, retract it downwards and dissect perirenal fat until you see the edge of the adrenal.

5. Dissect the ventral and lateral aspects of the adrenal gland by dividing small anterior branches until the adrenal vein is encountered. Division of the adrenal vein between clips or using a vascular stapler greatly increases mobility of the gland. Complete dissection of the adrenal, retrieve it in a bag and close the incisions.

Open posterior (retroperitoneal) approach

1. Make a horizontal incision over the eleventh rib, extended medially and superiorly over the paravertebral muscles. Excise the rib, carefully avoiding damage to the neurovascular bundle at the inferior margin of the rib.

2. Dissect the gland as described above, retrieve it in a bag and close the incision in layers.

3. Try not to damage the pleura, but if you do, reconstitute it at the end of the procedure. Do not insert a chest drain provided you have expressed all the air from the pleural cavity by expanding the lungs at the end of the procedure.

Anterior approach

Laparoscopic anterior approach

1. The first laparoscopic adrenalectomies were attempted using this approach but because of technical difficulty retracting structures, identifying the adrenals and controlling bleeding, as well as the duration of the procedure, it has been superseded by the lateral and posterior laparoscopic approaches.

Open anterior approach

1. Use either a transverse (rooftop) or midline abdominal incision.

2. Expose the left adrenal by dividing the lienorenal and lienocolic ligaments and retracting the splenic flexure downwards and spleen and pancreas medially. This provides good access to the adrenal and renal hilum and allows safe dissection of large tumours.

3. Expose the right adrenal by retracting the hepatic flexure of the colon downwards and performing Kocher’s manoeuvre to mobilize the duodenum. Divide the triangular ligaments of the right lobe of the liver and retract the liver medially, exposing its ‘bare area’ and the inferior vena cava. For large and infiltrating tumours encircle the inferior vena cava with tapes placed below and above the liver to provide safe control in case of major haemorrhage or if its resection and graft replacement are indicated.

4. Dissect the adrenal gland carefully and, after removing the tumour, close the abdomen using a mass closure technique. Abdominal drains are rarely required.

Postoperative

1. Postoperative management depends on the functional status of the removed adrenal, the size of the tumour and type of the operation performed (i.e. laparoscopic or open).

2. Patients following laparoscopic adrenalectomy for Conn’s syndrome can be nursed on the ward and go home after an overnight stay. Remember to check post operatively potassium and cortisol levels as some patients can suppress cortisol production in contralateral gland. They will require cortisol supplementation. Stop spironolactone and potassium supplementation. Gradually stop other medications for hypertension.

3. Manage most patients after surgery for Cushing’s syndrome/disease on the high dependency unit (HDU) overnight because they are often diabetic, obese, require careful fluid and electrolyte management and close cardiovascular monitoring. They also need treatment with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone.

4. Initial treatment of patients after removal of phaeochromocytoma must take place on the HDU as they require invasive cardiovascular monitoring of blood pressure, careful fluid replacement and may need adrenaline (epinephrine) or noradrenaline (norepinephrine) infusion.

Complications

1. Electrolyte abnormalities and hypertension are common in patients with hormonal syndromes. Correct them perioperatively to prevent cardiovascular incidents and strokes. Anticipate and treat the possibility of postoperative hypotension.

2. Failure to stop medications no longer required after surgery (e.g. phenoxybenzamine after resection of phaeochromocytoma) or prescribe new medications which are essential after adrenalectomy (e.g. hydrocortisone after adrenalectomy for Cushing’s syndrome) is a common mistake and can result in re-admission and endanger the patient’s life.

3. Bleeding during surgery may be the result of inadequate control of arteries and veins supplying the adrenal, or damage to surrounding structures such as the inferior vena cava, renal veins and arteries, liver or spleen. Carefully dissect and retract and sensibly employ the harmonic scalpel, diathermy, clips or vascular stapler to prevent this complication. Most adrenalectomies can be performed without blood transfusion. Postoperative bleeding is very rare.

4. Perforation of bowel (colon, stomach, or duodenum) may occur during introduction of trocars or adrenal dissection. Repair injuries detected during operation immediately – but the presentation of thermal injury to the bowel may be delayed by 24–48 hours.

5. Pancreatitis or pancreatic leak are rare complications of left adrenalectomy caused by excessive manipulation or damage to the pancreatic parenchyma.

6. Control postoperative pain with appropriate oral or parenteral analgesia; offer patients with large incisions epidural infusion or PCA (patient-controlled analgesia). Long-term pain may result from entrapment of intercostal nerves.