165 Adrenal Insufficiency

Historical Review

Historical Review

In the same decade, Hench and Kendall, two rheumatologists at the Mayo Clinic, found that in patients with different forms of rheumatism, the symptoms showed temporary remissions during pregnancy and inflammatory diseases like hepatitis. They speculated that this might be due to a general stimulation of the endocrine system and concluded that the use of cortisone might be beneficial in patients with acute rheumatoid arthritis. In September 1948, a female bedridden patient with severe and painful rheumatism that was resistant to all standard therapies at the time was the first documented case of cortisone treatment for inflammatory disease. After 3 days, the patient was able to stand up; 1 week later, she left the clinic without pain and on her own feet. Retrospectively, the speculations regarding pregnancy and hepatitis were obviously wrong, but the antiinflammatory character of cortisone was a key finding in pharmaceutical research. In contrast to Selye, who described cortisone as a crucial promoter of the physiologic stress response, the aforementioned finding that the adrenal gland cortex is the location for endogenous production of cortisone, an important inhibitor of stress and inflammation, has been confirmed. In 1950, Kendall, Hench, and Reichstein received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their historical findings on the physiologic role of the adrenal gland.1–4

Anatomy of the Adrenal Gland

Anatomy of the Adrenal Gland

The adrenal cortex receives afferent and efferent innervation. Direct contact of nerve terminals with adrenocortical cells has been suggested, and chemoreceptors and baroreceptors present in the adrenal cortex infer efferent innervation. Diurnal variation in cortisol secretion and compensatory adrenal hypertrophy are influenced by adrenal innervation. Splanchnic nerve innervation has an effect in regulating adrenal steroid release. The adrenal medulla secretes the catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine, that affect blood pressure, heart rate, sweating, and other activities also regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. The adrenal cortex is divided into three layers: (1) the zona glomerulosa, just under the capsule, (2) the zona fasciculata, the middle layer, and (3) the zona reticularis, the innermost net-like patterned area with reticular veins draining into medullary capillaries. The zona glomerulosa exclusively produces the mineralocorticoid, aldosterone; the zonae fasciculate and reticularis produce glucocorticoids and androgens.5

Physiology of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

Physiology of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

The adrenal glands are part of a complex system that produces interacting hormones to maintain physiologic integrity, especially during the stress response.6,7 This system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, includes the hypothalamic region which produces corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), triggering the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland is composed of two major structures: the adenohypophysis (anterior pituitary) and neurohypophysis (posterior pituitary). The anterior pituitary is responsible for the secretion of corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), growth hormone (GH), β-lipotropin, endorphins, prolactin, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The posterior pituitary secretes vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone [ADH]) and oxytocin. Corticotropin regulates the production of corticosteroids by the adrenal glands. Hypothalamic neurons receive input from many areas within the CNS; they integrate these inputs and initiate an output to the anterior pituitary via the median eminence. The median eminence secretes releasing hormones into a hypophyseal portal network of capillaries that connect the median eminence with the pituitary hormones.

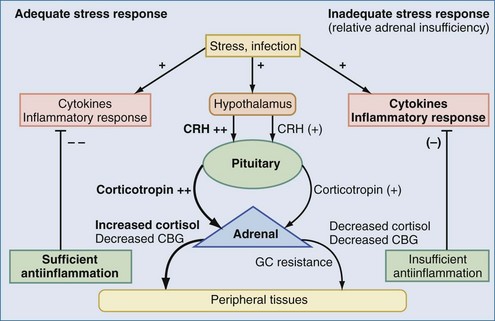

The HPA axis is stimulated not only by physical or psychic stress but also by peptides like ADH and cytokines. Thus, the HPA axis plays an important role during infections and immunologic disorders.8,9 By interaction with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) regulating fluid and salt balance, synthesis of androgens (e.g., dehydroepiandrosterone) with possible impact on immunomodulation, and the sympathoadrenergic system, the HPA axis is probably the most important organ of stress response. Stimulation of the immune system by infections induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, or IL-6. Following a cascade, these cytokines stimulate both the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary gland, which finally leads to the release of glucocorticoids. IL-6 is also able to induce steroid release directly from the adrenal gland. The adequate increase of glucocorticoid levels during inflammation is a crucial factor for appropriate stress response. In acute infections, this release maintains metabolic and energy integrity. If the process is chronic, the HPA axis develops an adaptation which induces typical clinical manifestations such as hypercatabolic states, hyperglycemia, and suppression of androgens and growth and thyroid hormones. These changes, however, may increase the risk for secondary infections. Increased cortisol levels suppress higher regulatory levels of the HPA axis in terms of a negative feedback loop. Hence, after major surgery or during sepsis and septic shock, high cortisol and low ACTH levels are detectable.10,11 Even the infusion of dexamethasone or CRH is not able to suppress increased cortisol levels in these patients.12,13 This phenomenon leads to the question of how cortisol release is induced. Several investigations demonstrated that adrenal cortisol synthesis in critically ill patients is not regulated by ACTH, but by paracrine pathways via endothelin, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), or cytokines like IL-6.14–16 IL-6 directly induces the adrenal cortex to release cortisol, which in chronic courses, can worsen the prognosis.17

Cellular Response to Adrenocortical Hormones and Related Drugs

Cellular Response to Adrenocortical Hormones and Related Drugs

Cortisol, the major free circulating adrenocortical hormone, is a hydrophobic hormone; being a steroid, it circulates bound to protein. Complexed cortisol-binding globulin (CBG, or transcortin) accounts for about 95% of circulating cortisol, but only the free form is biologically active. Its plasma half-life is 60 to 120 minutes. Cortisol is metabolized by hydroxylation in the liver, and the metabolites are excreted in urine. Steroid hormones enter the cytoplasm of cells where they combine with a receptor protein. Metabolic, immunologic, and hemodynamic responses to adrenocortical steroid hormones are regulated in a very complex manner that includes transactivation, transrepression, posttranscriptional/translational regulation, and nongenomic effects. The immediate nongenomic effects of steroid hormones were primarily attributed to mineralocorticoids (aldosterone). Rapid activation of the sodium-proton exchanger, increase of intracellular Ca++, and activation of second messenger pathways were described.18,19 A randomized trial in patients during cardiac catheterization revealed that within minutes after aldosterone injection, cardiac index and arterial pressure increased significantly for 10 minutes and returned to baseline afterwards.20 Interestingly, the genomic effects of aldosterone seemed to be mediated by binding to glucocorticoid (GC) receptors and not to mineralocorticoid receptors.21 There is evidence that GC, like cortisol, also modulates immune functions by rapid nongenomic effects via nonspecific interactions with cellular membranes and specific binding to membrane-bound GC receptors (GR).22 Nonspecific membrane effects have been demonstrated for inhibition of sodium and calcium cycling across plasma membranes by impairing Na+/K+-ATPase and Ca++-ATPase. Moreover, the rapid activation of lipocortin-1 and inhibition of arachidonic acid release after GC was independent from GR translocation. Finally, high-sensitivity immunofluorescence staining revealed membrane-bound GR on circulating B lymphocytes and monocytes.22

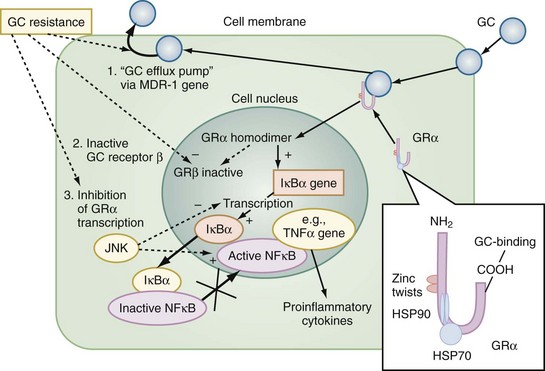

The multiple mechanisms by which GCs modulate cellular responses include mainly genomic pathways.23–25 Nongenomic effects are thought to account for immediate immune effects of high doses of GC, whereas membrane-bound receptors probably mediate low-dose GC effects. The classic model is that GCs bind to the cytoplasmatic ligand-regulated GC receptor alpha (GRα), which is an inactive multiprotein complex consisting of two heat shock proteins (hsp90) acting as molecular chaperones and other proteins (Figure 165-1). Upon GC binding to GRα, conformational change causes dissociation of hsp90, with subsequent nuclear translocation of GRα homodimers, binding of GRα to GC response elements (GRE) of DNA, and transcription of responsive genes (transactivation) such as lipocortin-1 and β2-adrenoreceptors. Alternatively, GRα may bind to negative GRE (nGRE) and repress transcription of genes (transrepression) such as pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). More importantly, transrepression without direct binding of GRα to GRE by protein-protein interactions of GRα with transcription factors, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and AP-1, has been recognized as a key step by which GC suppress inflammation,26 inhibiting synthesis of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, cell adhesion molecules, and growth factors, and promoting apoptosis.27 In addition, NF-κB repression may be mediated by GC-induced up-regulation of the cytoplasmatic NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα (see Figure 165-1) which prevents translocation of NF-κB.28 Clinical investigations provide support for the presence of endogenous GC inadequacy in the control of inflammation and peripheral GC resistance.29 With GC treatment, the intracellular relations between the NF-κB and GRα signaling pathways change from an initial NF-κB-driven and GRα-resistant state to a GRα-sensitive one. However, data are conflicting and probably do not explain early (<2 hours) suppressive effects of GC but may account for the longer-term dampening effect of GC on inflammatory processes.23

Figure 165-1 Cellular mechanisms of glucocorticoid effects (right) and glucocorticoid resistance (left).

Besides transcriptional regulation, posttranscriptional, translational, or posttranslational processes have been described for GC-induced modulation of COX-2, TNF-α, GM-CSF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and interferon gamma (IFN-γ).23 Furthermore, GCs act at multiple levels to regulate iNOS expression by decreased iNOS gene transcription and mRNA stability; reduced translation and increased degradation of the iNOS protein by the cysteine protease, calpain30; limitation of the availability of the NOS cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin; reduced transmembranous transport and de novo synthesis of the NOS substrate, L-arginine; and lipocortin-1-induced inhibition of iNOS.31,32 Together, these complex mechanisms result in the considerable effect of GC to inhibit inflammation and to stabilize hemodynamics. Finally, GC receptors have been found in nearly every nucleated cell in the body, and since each cell type has its own expression of GC effect, it follows that GCs have many effects in the body, which is equally true of endogenously produced GC hormones or exogenously administered GC medications. Both increase hepatic production of glucose and glycogen and decrease peripheral use of glucose. Steroids also affect fat and protein metabolism. They increase lipolysis both directly and indirectly by elevating free fatty acid levels in the plasma and enhancing any tendency to ketosis. GCs further stimulate peripheral protein metabolism, using the amino acid products as gluconeogenic precursors.

Definitions of Adrenal Insufficiency

Definitions of Adrenal Insufficiency

Adrenal glands may stop functioning when the HPA axis fails to produce sufficient amounts of the appropriate hormones. Primary adrenal insufficiency is defined by the inability of the adrenal gland to produce steroid hormones even when the stimulus by the pituitary gland via corticotropin is adequate or increased. Primary adrenal insufficiency affects 4 to 6 out of 100,000 people. The disease can strike at any age, with a peak between 30 and 50 years, and affects males and females about equally. In 70%, the cause is a primary destruction of the adrenal glands by an autoimmune reaction (“classical” Addison’s disease or autoimmune adrenalitis), with about 40% of patients having a history of associated endocrinopathies. Most adult patients have antibodies against the steroidogenic enzyme, 21-hydroxylase,33 but their role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune adrenalitis is uncertain. In the other 30%, the adrenal glands are destroyed by cancer, amyloidosis, antiphospholipid syndrome, adrenomyeloneuropathy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), infections (e.g., tuberculosis, cytomegaly, fungi), or other identifiable diseases (Box 165-1). In these cases, the typical morphologic changes of the adrenal cortex are atrophy, inflammation, and/or necrosis. In primary adrenal insufficiency, the whole adrenal cortex is involved, resulting in a deficiency of GCs, mineralocorticoids, and adrenal androgenes.34,35

Secondary adrenal insufficiency is characterized by adrenal hypofunction due to the lack of pituitary ACTH or hypothalamic CRH. Diseases of the anterior pituitary that can cause secondary adrenal insufficiency include neoplasms (e.g., craniopharyngiomas, adenomas), infarction (e.g., Sheehan’s syndrome, trauma), granulomatous disease (e.g., tuberculosis, sarcoidosis), hypophysectomy, and infection.36 Causes also include hypothalamic dysfunction, such as after irradiation or surgical interventions (see Box 165-1). Because aldosterone secretion is more dependent on angiotensin II than on ACTH, aldosterone deficiency is not a problem in secondary adrenal insufficiency. Selective aldosterone deficiency can occur as a result of depressed renin secretion and angiotensin II formation.34 Rare patients have an isolated deficiency of CRH,37 and lymphocytic hypophysitis with subsequent adrenal insufficiency was described in women.38 These disorders may lead to an isolated ACTH deficiency.34

The so-called tertiary adrenal insufficiency, which is often summarized together with secondary forms, commonly occurs after withdrawal of exogenous GCs. Many of these patients do well during normal activities but are unable to mount an appropriate GC response to stress. This effect depends on the dose and duration of treatment and varies greatly from person to person. It should be anticipated in any patient who has been receiving more than 30 mg of hydrocortisone per day (or 7.5 mg of prednisolone or 0.75 mg of dexamethasone per day) for more than 3 weeks.35 If supraphysiologic doses of GCs have been administered to a patient for more than 1 to 2 weeks, the drug should be tapered to allow for adrenal gland recovery. It may take 6 to 12 months for the adrenal glands to recover fully after prolonged use of exogenous GCs.39 Since ACTH is not a major determinant of mineralocorticoid production, the basic deficit in adrenal insufficiency is that of deficient GC production. It is important that neither the dose of applied glucocorticoids, nor the time of treatment, nor the basal plasma level of cortisol allow sufficient assessment of the function of the HPA axis. Some drugs have also been described to induce adrenal insufficiency, either by directly affecting adrenocortical steroid release (e.g., fluconazole, etomidate)40,41 or by enhanced hepatic metabolism of cortisol (e.g., rifampicin, phenytoin).35

Relative Adrenal Insufficiency

Relative Adrenal Insufficiency

The aforementioned forms of adrenal insufficiency which lead to an absolute deficiency of steroids are rare in critically ill patients (0%-3%).42 They are mostly characterized by morphologic changes of the HPA axis. To reflect the notion that subnormal adrenal corticosteroid production during acute severe illness can also occur without obvious structural defects in the HPA axis, deficiency syndromes due to a dysregulation have been termed functional adrenal insufficiency.43 Functional adrenal insufficiency can develop during the course of an illness and is usually transient.35 Decreased levels of GCs are registered much more often; these levels might be sufficient in normal subjects but are too low for stress situations, owing to higher need, and are associated with a worse outcome.44 This led to the concept of relative adrenal insufficiency (RAI). The major cause for RAI is inadequate synthesis of cortisol due to cellular dysfunction. Hence, in contrast to absolute adrenal insufficiency, the morphologic changes in RAI may be minor, sometimes characterized by cellular hyperplasia within the adrenal cortex. This is often combined with peripheral GC resistance of the target cells, which is caused by inflammatory events and aggravates the clinical course, although the absolute cortisol serum levels might be normal.45 In septic shock, RAI may be due to impaired pituitary corticotropin release, attenuated adrenal response to corticotropin, and reduced cortisol synthesis (Figure 165-2).35,46,47 In addition, cortisol transport capacity to effect sites may be reduced, and response to cortisol may be impaired at the tissue level by cytokines modulating GC receptor affinity to cortisol and/or GC response elements.48,49 In clinical trials, it was demonstrated that prolonged treatment of systemic inflammation in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with methylprednisolone can improve the decreased GC response by increasing the GC receptor affinity and reducing the NF-κB-mediated DNA binding and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines.29 Thus, if RAI can be identified, treatment with supplemental corticosteroids may be of benefit.35 Prevalence of RAI in the critically ill varied from 0% to 77% with different definitions, cutoff values, study populations, and adrenal function tests34,35,46,50,51 and may be as high as 50% to 75 % in severe septic shock.52

Evaluation of Adrenal Insufficiency

Evaluation of Adrenal Insufficiency

In clinical practice, assessment of adrenal function is difficult, especially in critically ill patients, since the diurnal rhythm is lost. Values indicating normal adrenocortical function are listed in Box 165-2. Normally, serum cortisol concentrations in the morning (8 AM) of less than 3 µg/dL (80 nmol/L) are strongly suggestive of absolute adrenal insufficiency,53 while values below 10 µg/dL (275 nmol/L) make the diagnosis likely. Basal urinary cortisol and 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion is low in patients with severe adrenal insufficiency but may be low-normal in patients with partial adrenal insufficiency. Generally, baseline urinary measurements are not recommended for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. To differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary adrenal insufficiency in cases of low cortisol, it is recommended to measure plasma ACTH concentrations simultaneously. Inappropriately low serum cortisol concentrations in association with increased ACTH concentrations are suggestive of primary adrenal insufficiency, whereas the combination of low cortisol and ACTH concentrations indicates secondary or tertiary disease. This, however, should be confirmed by stimulation of the adrenal gland with exogenous ACTH. In secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency, the adrenal glands release cortisol, whereas in primary adrenal insufficiency, the adrenal glands are partially or completely destroyed and do not respond to ACTH.

ACTH stimulation tests usually consist of administering 250 µg (40 International Units) of ACTH (so-called high-dose ACTH stimulation test). For long-term stimulation tests, which are preferred for differentiating between secondary and tertiary adrenal insufficiency, 250 µg of ACTH are infused either over 8 hours or over 2 days.54 Serum cortisol and 24-hour urinary cortisol and 17-hydroxycorticosteroid (17-OHCS) concentrations are determined before and after the infusion. This test may be helpful in distinguishing primary from secondary/tertiary adrenal insufficiency. In primary adrenal insufficiency, there is no or a minimal response of plasma or urinary cortisol and urinary 17-OHCS. Increases of these values in the 2 to 3 days of the test are indicative of a secondary/tertiary cause of adrenal insufficiency. In normal subjects, the 24-hour urinary 17-OHCS excretion increases 3- to 5-fold above baseline. Serum cortisol concentrations reach 20 µg/dL (550 nmol/L) at 30 to 60 min and exceed 25 µg/dL (690 nmol/L) at 6 to 8 hours post initiation of the infusion. Today this is not very often used, because clinical manifestations of adrenal insufficiency combined with basal cortisol levels, short-term ACTH stimulation tests, and CRH tests (see later) usually provide sufficient information.

A short-term stimulation test with 250 µg ACTH, mostly used for patients who are not critically ill, determines basal serum cortisol levels and the induced-response concentration 30 and 60 minutes after intravenous (IV) administration of ACTH. The advantage of the high-dose test is that pharmacologic plasma ACTH concentrations can be achieved by either IV or intramuscular injection.55 This way of application, however, may be too high to identify mild cases of secondary adrenal insufficiency or chronic deficiencies.56 Furthermore, it should not be used when acute secondary adrenal insufficiency (e.g., Sheehan’s syndrome) is presumed, since it takes several days for the adrenal cortex to atrophy, and it will still be capable of responding to ACTH stimulation normally. In these cases, a low-dose ACTH test or an insulin-induced hypoglycemia may be required to confirm the diagnosis.57,58 A rise in serum cortisol concentration after 30 or 60 minutes to a peak of 18 to 20 µg/dL (500 to 550 nmol/L) or more is considered a normal response to a high-dose ACTH stimulation test and excludes the diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency and almost all cases of secondary adrenal insufficiency except those of recent onset.59–61

To further differentiate between secondary and tertiary adrenal insufficiency, laboratory investigations may be augmented by a CRH stimulation test. In both conditions, cortisol levels are low at baseline and remain low after CRH. In patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency, there is little or no ACTH response, whereas in patients with tertiary disease, there is an exaggerated and prolonged response of ACTH to CRH stimulation which is not followed by an appropriate cortisol response.62,63 Formerly, the HPA axis was also tested by a stimulated hypoglycemia test. After administering 0.1 units of insulin per kilogram bodyweight, inducing a hypoglycemic state of less than 40 mg/dL serum glucose, an intact HPA axis induces a serum cortisol concentration of more than 20 µg/dL. Nowadays, this procedure is considered obsolete because of the high risk of hypoglycemia.

In critically ill patients, primary causes of absolute or relative adrenal insufficiencies are multiple and often undetectable if no specific hypothesis exists. Volume-resistant septic shock or any other form of life-threatening hypotension with increasing need for catecholamines should give reason to evaluate adrenal function. Formerly, a serum cortisol value less than 20 µg/dL was suggestive for the diagnosis. Meanwhile, it is acknowledged that several factors complicate investigations of the HPA axis in patients with critical illness. A short-term ACTH stimulation test may be performed in critically ill patients suspected of having adrenal insufficiency. However, in most patients, RAI will be present, especially in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. A clear definition of RAI is still missing, and the pathophysiology is rather complex, which makes it difficult to define clear cutoffs for both basal serum cortisol concentrations and incremental increases after short-term ACTH stimulation tests. Proposed cutoff points may depend on different methods used to measure cortisol, with variations when compared to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as the reference method.64 In addition, considering free cortisol or increase in free cortisol in response to ACTH could increase accuracy of adrenocortical function tests.48 Furthermore, extrapolating the diagnosis from reference values obtained from healthy people or patients with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal disorders may be misleading, since normal or high-normal cortisol concentrations in septic shock may indicate inadequate adrenal response to stress. In a large series of patients, receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis reached highest sensitivity (68%) and specificity (65%) for a reference value of less than 9 µg/dL (incremental increase) to detect nonresponders.52 Basal cortisol of 34 µg/dL and incremental increase of 9 µg/dL after stimulation were the best cutoff points to discriminate between survivors and nonsurvivors. The higher the basal plasma cortisol and the weaker the cortisol response to corticotropin, the higher was the risk of death. Some investigators have questioned the discriminative power of the incremental increase of cortisol after stimulation in patients with high basal cortisol values, as increases may reflect adrenal reserve more than adrenal function. Hence, RAI was defined based on the hemodynamic response when a randomly measured cortisol was less than 25 µg/dL.46

Routine use of the low ACTH stimulation test in critically ill patients cannot be recommended at present, although the low-dose test is preferred in patients with secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency.65 After stimulation with 250 µg ACTH, circulating corticotropin concentrations are 40 to 200 pg/mL during stress but may be as high as 60,000 pg/mL.35 Stimulation of the adrenal gland with low doses of ACTH (1 µg) was shown to increase sensitivity and specificity to detect adrenal insufficiency in patients with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal disorders who respond normally to traditional high-dose stimulation.35,66–69 The test is performed by measuring serum cortisol concentrations immediately before and 30 minutes after IV injection of ACTH in a dose of 1 µg (160 mIU) per 1.73 m2 body surface.34 This dose stimulates maximal adrenocortical secretion up to 30 minutes post injection, and in normal subjects results in a peak plasma ACTH concentration about twice that of insulin-induced hypoglycemia.70 A value of 18 µg/dL (500 nmol/L) or more at any time during the test is indicative of normal adrenal function. The advantage of this test is that it can detect partial adrenal insufficiency that may be missed by the standard high-dose test.57,58

Using the 1-µg ACTH stimulation test to more precisely uncover patients with RAI in septic shock has been proposed, but the 1-µg stimulation test has not been well validated in critically ill patients and patients with septic shock.34,35 In addition, studies evaluating low-dose and high-dose ACTH stimulation tests in septic shock may have been flawed by methodological problems. At present, using the 1-µg ACTH stimulation test cannot be recommended routinely until further data from well-designed randomized studies in septic shock patients are available. The current recommendation is to use a three-level therapeutic guide for evaluating RAI in critically ill patients, especially those with septic shock. Patients with a random basal cortisol below 15 µg/dL will likely profit from low-dose corticosteroid therapy, whereas corticosteroid replacement is unlikely to be helpful when basal cortisol is above 34 µg/dL. When a random basal cortisol value is between 15 and 34 µg/dL, adrenocortical stimulation with 250 µg ACTH should discriminate responders (incremental increase ≥ 9 µg/dL) from nonresponders (<9 µg/dL). However, it has been pointed out that no cutoff values will be entirely reliable.35

Clinical Symptoms

Clinical Symptoms

About 25% of patients with adrenal insufficiency present with adrenocortical crisis.34 The symptoms are nonspecific and include sudden dizziness, weakness, dehydration, hypotension, and shock (Box 165-3). In many cases, the clinical picture may be indistinguishable from shock due to loss of intravascular fluid volume. Other features such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and delirium may be present, but they are also common in patients with other acute illness. Hence, these symptoms may not be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency and are often misleading. Hypoglycemia is rare in acute adrenal insufficiency but more common in secondary adrenal insufficiency; it is a common manifestation in children and thin women with the disorder. Especially in patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), it remains extremely difficult to recognize an acute, absolute adrenal insufficiency based on clinical symptoms. However, if the diagnosis is missed, the patient will probably die, so the threshold for laboratory investigations in cases of unexplained catecholamine-resistant hypotension should be low. It is important to be mindful that the onset of an acute adrenocortical crisis is not necessarily an acute beginning of the underlying disease itself. The preceding course is often gradual and may go undetected until an acute illness, stress, trauma, pregnancy, or other conditions precipitate adrenal crisis.34,71

Box 165-3

Clinical Manifestations of Adrenal Insufficiency

In most cases, primary adrenal insufficiency is the underlying disorder. Typical symptoms such as hyperpigmentation, scanty axillary and pubic hair, hyponatremia, or hyperkalemia may be diagnosed in the acutely ill patient. Adrenal crisis can occur in patients receiving appropriate doses of GCs if their mineralocorticoid requirements are not met.72 After spontaneous events (e.g., hemorrhage, myocardial infarction, adrenal vein thrombosis), these signs are absent. If an acute adrenal crisis is suspected, a blood sample should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. The main clinical problem is hypotension and shock due to acute mineralocorticoid deficiency. This is one reason for the fact that an acute adrenal crisis after secondary adrenal insufficiency is not so typical. However, GC deficiency may also contribute to hypotension by decreasing vascular responsiveness to angiotensin II, norepinephrine, and other vasoconstrictive hormones, reducing the synthesis of renin substrate and increasing production and effects of prostacyclin and other vasodilatory hormones.73,74 Finally, panhypopituitarism may be associated with symptoms, owing not only to lack of corticotropin but also TSH, gonadotropin, and growth hormone.

In chronic adrenal insufficiency, the major clinical features (see Box 165-3) may be detected but may also be absent if adrenal gland insufficiency develops over a prolonged period of time. There is a stage characterized by normal basal steroid secretion but an inability to respond to stress. Hence, the patient may be asymptomatic. In other cases, there may also be signs and symptoms suggestive of other hormone deficiency such as decreased thyroid and gonadal function. Independent from the underlying cause, the most common clinical manifestations are general malaise, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, arthralgia, postural syncope, diarrhea that may alternate with constipation, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities (hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis), decreased axillary and pubic hair, and loss of libido and amenorrhea in women.34,71

In primary adrenal insufficiency, hyperpigmentation and autoimmune manifestations (vitiligo) are typically due to increased ACTH concentrations, whereas this is not seen in secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency. Soon after the disease develops, the skin becomes dark, which may appear to be tanning but appears on both sun-exposed and nonexposed areas. Black freckles develop on the forehead, face, and shoulders; a bluish-black discoloration may develop around the lips, mouth, rectum, scrotum, or vagina. Another specific symptom of primary adrenal insufficiency is a craving for salt.35 Typical laboratory abnormalities are hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, acidosis, slightly elevated creatinine concentrations, mild normocytic anemia, and rarely, hypercalcemia.35

In secondary adrenal insufficiency, since production of mineralocorticoids by the zona glomerulosa is mostly preserved, dehydration and hyperkalemia are not present, and hypotension is less prominent than in primary disease. Especially in the early stages, the onset of chronic adrenal insufficiency is often insidious, and the diagnosis may be difficult. Some patients initially present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps.35,75 In other patients, the disease may be misdiagnosed as depression or anorexia nervosa.76,77 Hyponatremia and increased intravascular volume may be the result of “inappropriate” increase in vasopressin secretion. Decreased libido and potency as well as amenorrhea may occur. Hypoglycemia is more common in secondary adrenal insufficiency, possibly due to concomitant growth hormone insufficiency, and in isolated ACTH deficiency. Clinical manifestations of a pituitary or hypothalamic tumor, such as symptoms and signs of deficiency of other anterior pituitary hormones, headache, or visual field defects, may also be present.34,71 Finally, in young patients suspected of having adrenal insufficiency, delayed growth and puberty would point to the presence of hypothalamic-pituitary disease, as would headaches, visual disturbances, or diabetes insipidus in patients of any age.35,36 Laboratory screening in patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency usually reveals hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, lymphocytosis, and eosinophilia.35

Therapeutic Strategies

Therapeutic Strategies

Treatment of adrenal insufficiency involves eradication of the precipitating cause (e.g., tumor, infection) and hormone replacement. In acutely ill patients, if the diagnosis of adrenal crisis is suspected but not known, blood should be obtained for measurement of cortisol concentrations, followed by the administration of 250 µg of ACTH in patients with unknown history. Therapy should be started immediately while awaiting results of testing.78 Dexamethasone (1 mg every 6 hours) may be given as the initial GC replacement, since it does not cross-react with cortisol in the plasma while adrenal testing is being performed. Patients are usually treated with IV fluids in the form of isotonic saline to restore intravascular volume and replace urinary salt losses. Dextrose infusion may be added to prevent hypoglycemia. Hydrocortisone (100 mg IV bolus or over 30 min, followed by continuous infusion of 10 mg/h, or 50 mg every 4 hours, or 75 to 100 mg every 6 hours, resulting in a total daily dose of 240-300 mg hydrocortisone) is frequently given for hormonal replacement.34,78 However, equivalent GC doses of methylprednisolone or dexamethasone may also be used. Typically, mineralocorticoid replacement therapy is not required in adrenal crisis so long as the patient is receiving isotonic saline. Prophylactic use of antibiotics is not beneficial, but specific infections should be treated aggressively with appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Once the patient is stable, or in cases of chronic adrenal insufficiency, GCs can be tapered to maintenance doses. Long-term replacement doses consist of hydrocortisone, 30 mg/d, with two-thirds (20 mg) given in the morning and one-third (10 mg) given at night; or prednisone, 7.5 mg in a similar regimen (5 and 2.5 mg, respectively). The daily dose may be decreased to 20 or 15 mg of hydrocortisone as long as the patient’s well-being and physical strength are not reduced.34 The goal should be to use the smallest dose that relieves the patient’s symptoms, in order to prevent weight gain and osteoporosis.34,78,79 If the patient continues to experience weakness or other symptoms of GC deficiency, the dose can be increased. Excessive GC therapy should be avoided so as to minimize complications of this therapy. In addition, a mineralocorticoid effect is provided with fludrocortisone (50-100 µg PO daily) to prevent sodium loss, intravascular volume depletion, and hyperkalemia, especially when the dose of hydrocortisone decreases below 100 mg/d. Therapy can be guided by monitoring blood pressure, serum potassium, and plasma renin activity, which should be in the upper normal range.34,61 Clinical response, however, is the best indicator of adequacy of replacement. The optimal dosage of mineralocorticoids remains stable over long periods. Excessive mineralocorticoid replacement may cause congestive heart failure, alkalosis, hypokalemia, or hypertension. Patients receiving prednisone or dexamethasone may require higher doses of fludrocortisone to lower their plasma renin activity to the upper normal range, whereas patients receiving hydrocortisone, which has some mineralocorticoid activity, may require lower doses. The mineralocorticoid dose may have to be increased in the summer, particularly if patients are exposed to temperatures above 29°C (85°F). In cases of isolated hypoaldosteronism, treatment includes liberal sodium intake and daily administration of fludrocortisone. In patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency due to panhypopituitarism, replacement with other hormones may also be necessary. In women, the adrenal cortex is the primary source of androgen in the form of dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. Although the physiologic role of these androgens in women has not been fully elucidated, their replacement is being increasingly considered in the treatment of adrenal insufficiency.80,81

Glucocorticoid Replacement in Patients with Septic Shock

Glucocorticoid Replacement in Patients with Septic Shock

In patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, the individual clinical course is extremely varied. The impact of the primary disease, as well as immunologic factors (cytokines), affect the HPA axis, and functional testing is aggravated. In contrast to the early phase of septic shock, adrenal cortisol release may recover, thus leading to RAI with absolute steroid levels around or even above normal range.82 In refractory septic shock, prevalence of RAI may be as high as 50% to 75%.52 Furthermore, dynamic testing is not always available in ICUs, which makes it difficult for the physician considering hormone replacement therapy, because decisions have to be made within hours in severe forms of septic shock to improve prognosis. Rationale for the use of high-dose GCs in infection, sepsis, and shock can be attributed to well-defined antiinflammatory and hemodynamic effects recognized for decades. Proposed mechanisms of protection include improvement of hemodynamic, metabolic, endocrine, and phagocytic functions, resulting in maintenance of normal morphologic-functional status of tissues including brain, liver, heart, kidneys, and adrenals.83 In addition, GCs were recognized to inhibit key features of inflammation: endothelial cell activation and damage, capillary leakage, granulocyte activation, adhesion and aggregation, complement activation, and formation and release of eicosanoid metabolites, oxygen radicals, and lysosomal enzymes.84–89

However, only in one long-term prospective study in humans receiving high doses of methylprednisolone (30-60 mg/kg) or dexamethasone (2-4 mg/kg), including 179 bacteremic septic shock patients over a period of 8 years, were experimental results confirmed and mortality reduced from 38% to 10%.90 Evidence from another study suggested that prolongation of treatment might have been beneficial, since shock reversal and improved survival occurred after bolus GC application in an early time window but vanished after several days.91 Two meta-analyses included 9 and 10 randomized trials, respectively, of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock who received up to 42 g of hydrocortisone equivalent or more; both concluded that high doses of corticosteroids were ineffective92 or harmful.93 This was confirmed by a large randomized trial in 1987.94 Patients with proven gram-negative infections probably benefited more from GCs.92 In one analysis, studies with the highest quality demonstrated worse outcomes with corticosteroids.93 High-dose GCs were associated with increased risk of secondary infections, mortality,93 and increased incidence of renal and hepatic dysfunction.95 Taken together, these results suggest that high-dose GCs failed to be effective in septic shock in the long run, most probably owing to immune system breakdown.

Similar to studies of high-dose GC treatment, numerous randomized controlled trials with low-dose corticosteroids in patients with septic shock also confirmed shock reversal and reduction of vasopressor support within few days after initiation of therapy in most patients.96–101 In a crossover study, mean arterial pressure and systemic vascular resistance increased during low-dose hydrocortisone treatment, and heart rate, cardiac index, and norepinephrine requirement decreased significantly.102 All effects were reversible with cessation of hydrocortisone. Some studies indicate that corticosteroid-induced increase of sensitivity to norepinephrine is more pronounced in patients with RAI than in patients without RAI.46,101 There are multiple potential mechanisms by which corticosteroids may modulate vascular tone. Considerable evidence confirms that cytokine-induced formation of nitric oxide (NO) plays a central role in vasodilation, catecholamine resistance, maldistribution of blood flow, and mitochondrial and organ dysfunction, and that the amount of NO production correlates with shock severity and outcome.103,104 In a crossover trial, norepinephrine requirement could be reduced by low-dose hydrocortisone in nearly all patients within 1 to 2 days. Hydrocortisone treatment also induced a significant and prolonged decline of nitrite/nitrate levels, which significantly correlated with reduction of norepinephrine requirement during hydrocortisone infusion.102 Considering the complex genomic and nongenomic actions of corticosteroids described earlier, it is probable that NO is not the only target. However, inhibition of NO synthesis by hydrocortisone at least contributes to shock reversal.

It is recognized that GCs modulate the stress response in a very complex manner that includes not only antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive actions to protect the host from overwhelming inflammation, but also immune-enhancing effects.27 The final effect of corticosteroids may be dependent on multiple factors such as the dose, type of cell or tissue, time point of action, and the balance of pro-inflammatory and antiinflammatory cofactors. Markers of the inflammatory response, antiinflammatory response, granulocyte, monocyte, and endothelial activation, antigen-presenting capacity, and innate immune response were investigated in septic shock patients.102 Hydrocortisone significantly attenuated inflammatory and antiinflammatory responses as well as granulocyte, monocyte, and endothelial activation. Monocyte HLA-DR expression was depressed, but receptor down-regulation was limited and followed by a rebound increase after drug withdrawal.102 One could thus conclude that the immune effects of low-dose hydrocortisone treatment in septic shock may be characterized as immunomodulatory rather than immunosuppressive. Attenuation of a broad spectrum of the inflammatory response without causing severe immunosuppression might be a promising therapeutic approach, which goes far beyond hemodynamic stabilization.

Although data on outcome in septic shock patients after low-dose corticosteroid treatment are limited, up to 300 mg hydrocortisone per day may improve survival. In most trials with low-dose corticosteroids,96–100 28-day all-cause mortality was reduced, whereas in high-dose trials, there was no significant effect. In a multicenter trial in 300 patients with severe volume and catecholamine-refractory septic shock, survival time was significantly increased in patients with RAI but not in responders to ACTH.97 Similar results were obtained for ICU and hospital mortality, but not for 1-year follow-up. Significant increases of serious adverse events during treatment with low-dose hydrocortisone have not been reported. The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, superinfections, or hyperglycemia has not been different in patients treated with corticosteroids or placebo, and wound infections were even less frequent in patients treated with low-dose hydrocortisone.97 These findings were not confirmed by another large randomized trial, the Corticosteroid Therapy of Septic Shock (CORTICUS) trial105 which, however, used different inclusion criteria. Only patients who were successfully resuscitated by volume therapy plus applied vasopressor were included.105 These contradictory results led the Surviving Sepsis Campaign to redefine their guidelines in 2008,106 recommending the use of low-dose GCs only for patients who are not responding adequately to volume plus vasopressor therapy—that is, those who are still hypotensive.106

Treatment with low-dose hydrocortisone may induce an increase of sodium levels within a few days, and hypernatremia with values over 155 mmol/L have been reported during prolonged treatment.100 Nevertheless, the indication for low-dose corticosteroids should be weighed against possible risks, and treatment should be limited to the duration of volume- and vasopressor-restrictive hypotension.

Dosing of hydrocortisone in septic shock is similar to adrenal crisis (100 mg initial bolus, followed by 200-300 mg per day), and the dose should be tapered when the patient stabilizes. Hydrocortisone should be preferred, although a comparative study of different corticosteroids has not been performed in septic shock, since most experience of low-dose corticosteroid treatment in septic shock was derived from studies using hydrocortisone (see earlier). Furthermore, hydrocortisone is the synthetic equivalent to the physiologic final active compound, cortisol, so treatment with hydrocortisone directly replaces cortisol independently from metabolic transformation. Finally, in contrast to dexamethasone, hydrocortisone has intrinsic mineralocorticoid activity. A recent randomized trial demonstrated that the addition of oral fludrocortisone to low-dose hydrocortisone has no benefit in septic shock patients.107 It has not been established whether a weight-adjusted regimen (e.g., 0.18 mg/kg/h)56 of continuous hydrocortisone infusion is superior to a fixed regimen; moreover, a comparative study of bolus versus infusion regimens has not been performed so far. Patients should be weaned from low-dose hydrocortisone over several days to avoid hemodynamic and immunologic rebound effects. In patients with septic shock, abrupt cessation of low-dose hydrocortisone was followed by significant reversal of many hemodynamic and immunologic effects observed during corticosteroid therapy, even after a short treatment period of 3 days.102 Adrenal function tests with 250 µg ACTH can be performed in patients with septic shock; however, at present it cannot be recommended to exclude responders or patients with high random cortisol values from low-dose corticosteroid therapy.35 When basal serum cortisol concentrations are less than 15 µg/dL in septic shock, low-dose hydrocortisone replacement is recommended; levels of over 34 µg/dL are considered sufficient. Between 15 and 34 µg/dL, an incremental increase of less than 9 µg/dL serum cortisol makes relative adrenal insufficiency likely, and therapy may be considered according to the clinical state.35 Other recommendations prefer a randomly assigned cutoff level of below 25 µg/dL serum cortisol.46 The routine use of the low ACTH stimulation test (1 µg ACTH) cannot be recommended at present until further data from well-designed randomized studies in septic shock patients are available. Most importantly, it has to be realized that all the aforementioned studies were performed in patients with catecholamine-resistant septic shock. So far there are no data justifying the use of low-dose steroids in patients with sepsis and severe sepsis. Significant effects on outcome have been observed only in patients with systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg despite vasopressor therapy.97 It is not yet known whether low-dose corticosteroids are also effective in patients with less severe shock. Sufficient data on the dose-response characteristics of GCs in septic patients are still lacking, and the current recommended strategy using 200 to 300 mg hydrocortisone per day is based on empirical recommendations; further investigations are needed.

Further Implications for Anesthesia and Critical Care

Further Implications for Anesthesia and Critical Care

Surgical stress increases serum cortisol levels five- to sixfold postoperatively, with return to normal at 24 hours unless stress continues. Patients who have received GCs equivalent to 30 mg/d cortisol for longer than 3 weeks may have impairment in this stress response, and steroid supplementation should be considered. However, short-term treatment of heterogeneous groups of patients with critical illness is controversial, and supraphysiologic doses of GCs are not beneficial and may even be harmful.108 Hence, outside the situations in which benefit has been proved, supraphysiologic doses of GCs (e.g., 30 mg methylprednisolone per kilogram of body weight per day) in patients with critical illness are not indicated. Some successful indications, however, have been described: in patients with unresolving ARDS, pharmacologic doses (2 mg methylprednisolone/kg/d) reduced mortality and improved organ function.29 Furthermore, early treatment with dexamethasone may decrease morbidity in bacterial meningitis,109,110 although a recent meta-analysis was less enthusiastic.111 The positive effects of steroid treatment on tissue-specific resistance to GCs have already been described. However, despite the frequent suggestion that unexplained intraoperative hypotension and even death reflect unrecognized hypocortisolism, there is no evidence that primary adrenal insufficiency is a likely explanation for this response.

Patients with known chronic adrenal insufficiency must be advised to double or triple the dose of hydrocortisone temporarily whenever they have any febrile illness or injury.34 In stressful situations or during major surgery, trauma, burns, or medical illness, high doses of GCs up to 10 times the daily production are required to avoid an adrenal crisis, although no data from randomized trials are available. A continuous infusion of 10 mg of hydrocortisone per hour or the equivalent amount of dexamethasone or prednisolone eliminates the possibility of GC deficiency. This dose can be halved the second postoperative day, and the maintenance dosage can be resumed the third postoperative day. However, it is important that with regard to possible detrimental effects and the possibility of decreased resistance to infections, this treatment should not be used for prolonged periods in the absence of evidence of corticosteroid insufficiency. General perioperative management should include avoidance of etomidate as an anesthetic drug (selection of other drugs and muscle relaxants is not influenced by the presence of treated hypocortisolism), infusion of sodium-containing fluids, minimal doses of any anesthetic drugs to avoid increased sensitivity to drug-induced myocardial depression, invasive monitoring of hemodynamics, glucose, and electrolytes, and decreased initial doses of muscle relaxant, monitoring the effect using a peripheral nerve stimulator. Especially when acute adrenal insufficiency has been detected in a critically ill patient with a previously unknown disorder, thorough diagnostics are demanded even after improvement.

Observations suggest that control of cortisol secretion in response to stress is more complex than originally thought. Interactions between corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, arginine vasopressin, catecholamines, and other hormones in the control of cortisol secretion have been described.112 α2-Adrenergic receptor antagonists (e.g., clonidine), which are widely used in ICUs, may suppress the cortisol response to surgical stress. On the other hand, increases in intracranial pressure stimulate cortisol release without increasing ACTH levels, and adrenalectomy but not adrenal demedullation increased the permeability of brain tissue to macromolecules.113 Further evidence also suggests that white blood cells may release ACTH-like peptides that can stimulate adrenal gland secretion of cortisol, and that primary adrenal insufficiency is associated with increases in serum levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme.114

There are multiple interactions between drugs and the HPA axis that have to be considered if absolute or relative adrenal insufficiency is suspected. Moreover, in patients with hepatic dysfunction, GC doses should be tapered, especially when using prednisone, since hydroxylation to the active component needs considerable metabolic capacity. Special attention is required in the concomitant use of GCs with other drugs, because of potential interactions and because some drugs may affect the metabolism of steroids, which may lead to a decreased or increased GC effect on their target tissues.115,116 Glucocorticoids decrease blood levels of aspirin, coumarin anticoagulants, isoniazid, insulin, and oral hypoglycemic agents, whereas cyclophosphamide and cyclosporine levels may be increased. Inversely, antacids, carbamazepine, cholestyramine, colestipol, ephedrine, mitotane, phenobarbitone, phenytoin, and rifampicin decrease GC blood concentrations, whereas they are increased by cyclosporine, erythromycin, oral contraceptives, and troleandomycin. Furthermore, the combination of exogenous GC administration and amphotericin B, digitalis glycosides, and potassium-depleting diuretics may induce or worsen hypokalemia, warranting frequent monitoring of potassium levels. Finally, the general risk for immunosuppression by GCs precludes any use of vaccines from live attenuated viruses to avoid severe generalized infections.115,116

Key Points

Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, Briegel J, Confalonieri M, De Gaudio R, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;301:2362-2375.

Liberman AC, Druker J, Garcia FA, Holsboer F, Arzt E. Intracellular molecular signaling. Basis for specificity to glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory actions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:6-13.

Loriaux DL, Fleseriu M. Relative adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16:392-400.

Keh D, Boehnke T, Weber-Carstens S, Schulz C, Ahlers O, Bercker S, et al. Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of “low-dose” hydrocortisone in septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:512-520.

Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, Bollaert PE, Francois B, Korach JM, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862-871.

Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, et alCORTICUS Study Group. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111-124.

1 Munck A. Glucocorticoid biology—a historical perspective. In: Goulding NJ, Flower RJ, editors. Glucocorticoids. Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhaeuser Verlag; 2001:17-33.

2 Zimmerman JJ. A history of adjunctive glucocorticoid treatment for pediatric sepsis: moving beyond steroid pulp fiction toward evidence-based medicine. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(6):530-539.

3 Selye H. The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1946;6:117-230.

4 Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, et al. The effect of a hormone of the adrenal cortex (17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone: Compound E) and of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone on rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1949;24:181-197.

5 Barwick TD, Malhotra A, Webb JA, Savage MO, Reznek RH. Embryology of the adrenal glands and its relevance to diagnostic imaging. Clin Radiol. 2005;60(9):953-959.

6 Lightman SL. The neuroendocrinology of stress: a never-ending story. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(6):880-884.

7 Summers CH, Winberg S. Interactions between the neuronal regulation of stress and aggression. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:4581-4589.

8 Papadimitriou A, Priftis KN. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(5):265-271.

9 Pérez AR, Bottasso O, Savino W. The impact of infectious diseases upon neuroendocrine circuits. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(2):96-105.

10 Marques AH, Silverman MN, Sternberg EM. Glucocorticoid dysregulations and their clinical correlates. From receptors to therapeutics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:1-18.

11 Holsboer F, Ising M. Stress hormone regulation: biological role and translation into therapy. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61:81-109.

12 Maxime V, Siami S, Annane D. Metabolism modulators in sepsis: the abnormal pituitary response. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9 Suppl):S596-S601.

13 Kloeckner M, Gallet de Saint-Aurin R, Polito A, Aboab J, Annane D. Corticotropin axis in septic shock. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2007;68(4):281-289.

14 Nijm J, Jonasson L. Inflammation and cortisol response in coronary artery disease. Ann Med. 2009;41(3):224-233.

15 Pace TW, Miller AH. Cytokines and glucocorticoid receptor signaling. Relevance to major depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:86-105.

16 Barnes PJ. Mechanisms and resistance in glucocorticoid control of inflammation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120:76-85.

17 Päth G, Bornstein SR, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, et al. Interleukin-6 and the interleukin-6-receptor in the human adrenal gland: expression and effects on steroidogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2343-2349.

18 Lösel RM, Feuring M, Falkenstein E, et al. Nongenomic effects of aldosterone: cellular aspects and clinical implications. Steroids. 2002;67(6):493-498.

19 Mihailidou AS. Nongenomic actions of aldosterone: physiological or pathophysiological role? Steroids. 2006;71(4):277-280.

20 Grossmann C, Gekle M. New aspects of rapid aldosterone signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;308(1-2):53-62.

21 Okada Y, Tanikawa T, Iida T, Tanaka Y. Vascular injury by glucocorticoid; involvement of apoptosis of endothelial cells. Clin Calcium. 2007;17(6):872-877.

22 Stahn C, Buttgereit F. Genomic and nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4(19):525-533.

23 Liberman AC, Druker J, Garcia FA, Holsboer F, Arzt E. Intracellular molecular signaling. Basis for specificity to glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory actions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:6-13.

24 De Brosscher K, Haegemann G. Minireview: latest perspectives on antiinflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(3):281-291.

25 Chrousos GP, Kino T. Glucocorticoid signaling in the cell. Expanding clinical implications to complex human behavioral and somatic disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:153-166.

26 Neumann M, Naumann M. Beyond IkappBs: alternative regulation of NF-kappaB activity. FASEB J. 2007;21(11):2642-2654.

27 Landys MM, Ramenofsky M, Wingfield JC. Actions of glucocorticoids at a seasonal baseline as compared to stress-related levels in the regulation of periodic life processes. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;148(2):132-149.

28 Hayashi R, Wada H, Ito K, Adcock IM. Effects of glucocorticoids on gene transcription. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500(1-3):51-62.

29 Meduri GU, Annane D, Chrousos GP, Marik PE, Sinclair SE. Activation and regulation of systematic inflammation in ARDS: rationale for prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. Chest. 2009;136(6):1631-1643.

30 Marchetti B, Serra PA, Tirolo C, L’episcopo F, Caniglia S, Gennuso F, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor-nitric oxide crosstalk and vulnerability to experimental parkinsonism: pivotal role for glia-neuron interactions. Brain Res Rev. 2005;48(2):302-321.

31 Simmons WW, Ungureanu-Longrois D, Smith GK, et al. Glucocorticoids regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase by inhibiting tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis and L-arginine transport. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(39):23928-23937.

32 Wu CC, Croxtall JD, Perretti M, et al. Lipocortin 1 mediates the inhibition by dexamethasone of the induction by endotoxin of nitric oxide synthase in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(8):3473-3477.

33 Sharma D, Mukherjee R, Moore P, Cuthbertson DJ. Addison’s disease presenting with idiopathic intracranial hypertension in 24-year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:60.

34 Cooper MS, Stewart PM. Adrenal insufficiency in critical illness. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22(6):348-362.

35 Marik PE. Critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency. Chest. 2009;135(1):181-193.

36 Fernandez A, Brada M, Zabuliene L, Karavitaki N, Wass JA. Radiation-induced hypopituitarism. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16(3):733-772.

37 Ferraz-de-Souza B, Achermann JC. Disorders of adrenal development. Endocr Dev. 2008;13:19-32.

38 Abe T. Lymphocytic infundibulo-neurohypophysitis and infundibulo-panhypophysitis regarded as lymphocytic hypophysitis variant. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2008;25(2):59-66.

39 Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

40 Santhana Krishnan SG, Cobbs RK. Reversible acute adrenal insufficiency caused by fluconazole in a critically ill patient. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(971):e23.

41 Lundy JB, Slane ML, Frizzi JD. Acute adrenal insufficiency after a single dose of etomidate. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22(2):111-117.

42 Jacobi J. Corticosteroid replacement in critically ill patients. Crit Care Clin. 2006;22(2):245-253.

43 Burchard K. A review of the adrenal cortex and severe inflammation: quest of the “eucorticoid” state. J Trauma. 2001;51:800-814.

44 Hahner S, Allolio B. Therapeutic management of adrenal insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23(2):167-179.

45 Annetta M, Maviglia R, Proietti R, Antonelli M. Use of corticosteroids in critically ill septic patients: a review of mechanisms of adrenal insufficiency in sepsis and treatment. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10(9):887-894.

46 Annane D. Adrenal insufficiency in sepsis. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(9):1882-1886.

47 Cohen J, Venkatesh B. Relative adrenal insufficiency in the intensive care population: background and critical appraisal of the evidence. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38(3):425-436.

48 Torpy DJ, Ho JT. Value of free cortisol measurements in systemic infection. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39(6):439-444.

49 Bornstein SR, Engeland WC, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Herman JP. Dissociation of ACTH and glucocorticoids. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19(5):175-180.

50 Loriaux DL, Fleseriu M. Relative adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16(5):392-400.

51 Iribarren JL, Jiménez JJ, Hernández D, Lorenzo L, Brouard M, Milena A, et al. Relative adrenal insufficiency and hemodynamic status in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery patients. A prospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:26.

52 Annane D, Sebille V, Troche G, et al. A 3-level prognostic classification in septic shock based on cortisol levels and cortisol response to corticotropin. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1038-1045.

53 Hägg E, Asplund K, Lithner F. Value of basal plasma cortisol assays in the assessment of pituitary-adrenal insufficiency. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;26(2):221-226.

54 Rose LI, Williams GH, Jagger PI, et al. The 48-hour adrenocorticotropin infusion test for adrenocortical insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:49-54.

55 Longui CA, Vottero A, Harris AG, et al. Plasma cortisol responses after intramuscular corticotropin 1-24 in healthy men. Metabolism. 1998;47:1419-1424.

56 Streeten DHP, Anderson GHJr, Bonaventura MM. The potential for serious consequences from misinterpreting normal responses to the rapid adrenocorticotropin test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:285-293.

57 Rasmuson S, Olsson T, Hagg E. A low dose ACTH test to assess the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;44:151-155.

58 Thaler LM, Blevins LSJr. The low dose (1 µg) adrenocorticotropin stimulation test in the evaluation of patients with suspected central adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2726-2729.

59 Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, et al. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72(4):773-778.

60 Crowley S, Hindmarsh PC, Honour JW, et al. Reproducibility of the cortisol response to stimulation with a low dose of ACTH(1-24): The effect of basal cortisol levels and comparison of low-dose with high-dose secretory dynamics. J Endocrinol. 1993;136:167-173.

61 Oelkers W, Diederich S, Bahr V. Diagnosis and therapy surveillance in Addison’s disease: Rapid adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) test and measurement of plasma ACTH, renin activity, and aldosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:259-265.

62 Schulte HM, Chrousos GP, Avgerinos P, et al. The corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test: A possible aid in the evaluation of patients with adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;58:1064.

63 Gold PW, Kling MA, Khan I, et al. Corticotropin releasing hormone: relevance to normal physiology and to the pathophysiology and differential diagnosis of hypercortisolism and adrenal insufficiency. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1987;43:183-200.

64 Tunn S, Pappert G, Willnow P, et al. Multicentre evaluation of an enzyme-immunoassay for cortisol determination. J Clin Chem Biochem. 1990;28:929-935.

65 Abdu TAM, Elhadd TA, Neary E, et al. Comparison of the low dose short Synacthen test (1 µg), the conventional dose short Synacthen test (250 µg), and the insulin tolerance test for assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:838.

66 Miller AH, Pariante CM, Pearce BD. Effects of cytokines on glucocorticoid receptor expression and function. Glucocorticoid resistance and relevance to depression. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;461:107-116.

67 Dökmetas HS, Colak R, Kelestimur F, et al. A comparison between the 1-microg adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) test, the short ACTH (250 microg) test, and the insulin tolerance test in the assessment of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis immediately after pituitary surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3713-3719.

68 Zarkovic M, Ciric J, Stojanovic M, et al. Optimizing the diagnostic criteria for standard (250-microg) and low dose (1-microg) adrenocorticotropin tests in the assessment of adrenal function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3170-3173.

69 Mayenknecht J, Diederich S, Bahr V, et al. Comparison of low and high dose corticotropin stimulation tests in patients with pituitary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1558-1562.

70 Nye EJ, Grice JE, Hockings GI, et al. Comparison of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) stimulation tests and insulin hypoglycemia in normal humans: low dose, standard high dose, and 8-hour ACTH-(1-24) infusion tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(10):3648-3655.

71 Stewart PM. The adrenal cortex. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003:525-532.

72 Cronin CC, Callaghan N, Kearney PJ, et al. Addison disease in patients treated with glucocorticoid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:456.

73 Ohtani R, Yayama K, Takano M, et al. Stimulation of angiotensinogen production in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes by glucocorticoid, cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate, and interleukin-6. Endocrinology. 1992;130:1331.

74 Jeremy JY, Dandona P. Inhibition by hydrocortisone of prostacyclin synthesis by rat aorta and its reversal with RU486. Endocrinology. 1986;119:661.

75 Tobin MV, Aldridge SA, Morris AI, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Addison’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1302-1305.

76 Tobin MV, Morris AI. Addison’s disease presenting as anorexia nervosa in a young man. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:953-955.

77 Keljo DJ, Squires RHJr. Just in time. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:46-48.

78 Werbel SS, Ober KP. Acute adrenal insufficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1993;22:303-328.

79 Zelissen PM, Croughs RJM, van Rijk PP, et al. Effect of glucocorticoids replacement therapy on bone mineral density in patients with Addison disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:207-210.

80 Arlt W, Callies F, van Vlijmen JC, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in women with adrenal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(14):1013-1020.

81 Callies F, Fassnacht M, van Vlijmen JC, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in women with adrenal insufficiency: effects on body composition, serum leptin, bone turnover, and exercise capacity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(5):1968-1972.

82 Wallace I, Cunningham S, Lindsay J. The diagnosis and investigation of adrenal insufficiency in adults. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46(Pt 5):351-367.

83 Boyer A, Chadda K, Salah A, Annane D. Glucocorticoid treatment in patients with septic shock: effects on vasopressor use and mortality. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;44(7):309-318.

84 Skubitz KM, Craddock PR, Hammerschmidt DE, et al. Corticosteroids block binding of chemotactic peptide to its receptor on granulocytes and cause disaggregation of granulocyte aggregates in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1981;68:13-20.

85 Hammerschmidt DE, White JG, Craddock PR, et al. Corticosteroids inhibit complement-induced granulocyte aggregation. A possible mechanism for their efficacy in shock states. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:798-803.

86 Goldstein JM, Roos D, Weisman G, et al. Influence of corticosteroids on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte function in vitro: Reduction of lysosomal enzyme release and superoxide production. Inflammation. 1976;1:305-315.

87 Flower RJ, Blackwell GJ. Anti-inflammatory steroids induce biosynthesis of a phospholipase A2 inhibitor which prevents prostaglandin generation. Nature. 1979;278:456-459.

88 Sibbald WJ, Driedger AA, Finley RJ, et al. High-dose corticosteroids in the treatment of pulmonary microvascular injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;384:496-516.

89 Jacob HS, Craddock PR, Hammerschmidt DE, et al. Complement-induced granulocyte aggregation: an unsuspected mechanism of disease. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:789-794.

90 Schumer W. Steroids in the treatment of clinical septic shock. Ann Surg. 1976;184:333-341.

91 Sprung CL, Caralis PV, Marcial EH, et al. The effects of high-dose corticosteroids in patients with septic shock. A prospective, controlled study. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1137-1143.

92 Lefering R, Neugebauer EA. Steroid controversy in sepsis and septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 1985;23:1294-1303.

93 Cronin L, Cook DJ, Carlet J, et al. Corticosteroid treatment for sepsis: a critical appraisal and meta-analysis of the literature. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1430-1439.

94 Bone RC, Fisher CJ, Clemmer TP, et al. A controlled trial of high-dose methylprednisolone in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:653-658.

95 Slotman GJ, Fisher CJJr, Bone RC, et al. Detrimental effects of high-dose methylprednisolone sodium succinate on serum concentrations of hepatic and renal function indicators in severe sepsis and septic shock. The Methylprednisolone Severe Sepsis Study Group. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:191-195.

96 Briegel J, Kellermann W, Forst H, et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone infusion attenuates the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The Phospholipase A2 Study Group. J Clin Invest. 1994;72:782-787.

97 Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862-871.

98 Bollaert PE, Charpentier C, Levy B, et al. Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic doses of hydrocortisone. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:645-650.

99 Yildiz O, Doganay M, Aygen B, et al. Physiological-dose steroid therapy in sepsis. Crit Care. 2002;6:251-259.

100 Briegel J, Forst H, Haller M, et al. Stress doses of hydrocortisone reverse hyperdynamic septic shock: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, single-center study. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:723-732.

101 Oppert M, Reincke A, Gräf KJ, et al. Plasma cortisol levels before and during “low-dose” hydrocortisone therapy and their relationship to hemodynamic improvement in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1747-1755.

102 Keh D, Boehnke T, Weber-Carstens S, et al. Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of “low-dose” hydrocortisone in septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:512-520.

103 Vincent JL, Zhang H, Szabo C, et al. Effects of nitric oxide in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(6):1781-1785.

104 Landry DW, Oliver JA. The pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):588-595.

105 Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, et alCORTICUS Study Group. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111-124.

106 Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(1):17-60.

107 COIITSS Study InvestigatorsAnnane D, Cariou A, Maxime V, Azoulay E, D’honneur G, Timsit JF, et al. Corticosteroid treatment and intensive insulin therapy for septic shock in adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(4):341-348.

108 Lamberts SWJ, Bruining HA, de Jong FH. Corticosteroid therapy in severe illness. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1285-1292.

109 Van den Beek D, de Gans J. Dexamethasone in adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Drugs. 2006;66(4):415-427.

110 Weisfelt M, de Gans J, van den Beek D. Bacterial meningitis: a review of effective pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8(10):1493-1504.

111 van den Beek D, Farrar JJ, de Gans J, Mai NT, Molyneux EM, Peltola H, et al. Adjunctive dexamethasone in bacterial meningitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(3):254-263.

112 Axelrod J, Reisine TD. Stress hormones: their interaction and regulation. Science. 1984;224(4648):452-459.

113 Long JB, Holaday JW. Blood-brain barrier: endogenous modulation by adrenal-cortical function. Science. 1985;227(4694):1580-1583.

114 Falezza G, Lechi Santonastaso C, Parisi T, et al. High serum levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme in untreated Addison’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61(3):496-498.

115 Liapi C, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoids. In: Jaffe SJ, Aranda JV, editors. Pediatric Pharmacology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, USA: WB Saunders Co; 1992:466-475.

116 Magiakou MA, Chrousos GP. Corticosteroid therapy, nonendocrine disease and corticosteroid withdrawal. In: Bardin CW, editor. Current Therapy in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 5th ed. Philadelphia, USA: Mosby Yearbook; 1994:120-124.