Chapter 34 Adoption

Role of Pediatricians

Preadoption Medical Record Reviews

The nature and quality of preadoption medical records of children living outside of the USA vary widely. Poor translation and use of medical terminology and medications that are unfamiliar to U.S. trained physicians are quite common. Results of specific diagnostic studies and laboratory tests performed in the child’s home country should not be relied on and should be repeated once the child arrives in the USA. Paradoxically, review of the child’s medical records may raise more questions than provide answers. Each medical diagnosis should be considered carefully before being rejected or accepted. Country-specific growth curves should be avoided as they may be inaccurate or reflect a general level of poor health and nutrition in the country of origin. Instead, serial growth data should be plotted on U.S. standard growth curves; they may reveal a pattern of poor growth due to malnutrition or other chronic illness. Photographs or videotapes/DVDs may provide the only objective data regarding a child’s health status. The quality of this information, however, is often of questionable value. Nonetheless, full-face photographs may reveal dysmorphic features consistent with fetal alcohol syndrome (Chapter 100.2) or findings suggestive of other congenital disorders.

Postadoption Care

Arrival Visit

After the child is settled in the new home, pediatricians should encourage adoptive parents to seek a comprehensive assessment of the child’s health and development. The unique medical and developmental needs of internationally adopted children have led to the creation of specialty clinics throughout the USA. A significant number of internationally adopted children have acute or chronic medical problems, including growth deficiencies, anemia, elevated blood lead, dental decay, strabismus, birth defects, developmental delay, feeding and sensory difficulty, and social-emotional concerns (Chapter 34.1). All children with symptoms of an acute illness should receive immediate medical care. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children who are adopted from other countries undergo routine screening for infectious diseases and disorders of growth, development, vision, and hearing (Tables 34-1 and 34-2). Additional tests (e.g., malaria) should be ordered depending on the prevalence of disease in the child’s country of origin. If the child’s PPD is negative, a repeat skin test should be performed in 4-6 mo, since children may have false negative tests due to poor nutrition. A positive PPD should be followed by a QuantiFERON-TB Gold test to determine if the response is the result of prior BCG vaccination (Chapter 207). If they have not received hepatitis A vaccine prior to leaving the USA, parents and other household contacts (siblings, grandparents, etc.) should also be immunized. In 1 survey, 65% of internationally adopted children had no written records of overseas immunizations; however, those with records appeared to have valid records, although doses were not necessarily acceptable according to the U.S. schedule (Chapter 165).

Table 34-1 RECOMMENDED SCREENING TESTS FOR NEWLY ARRIVING ADOPTEES

Screening tests

Other screening tests to consider based on clinical findings and age of the child

Infectious disease screening (see Table 34-2)

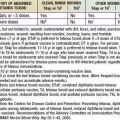

Table 34-2 SCREENING TESTS FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES IN IMMIGRANT CHILDREN

RECOMMENDED TESTS

OPTIONAL TESTS (FOR SPECIAL POPULATIONS OR CIRCUMSTANCES)

ART, automated reagin test; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption; MHA-TP, microhemagglutination test for Treponema pallidum; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratories.

Beckett C, Maughan B, Rutter M, et al. Do the effects of early severe deprivation on cognition persist into early adolescence? Findings from the English and Romanian Adoptees Study. Child Dev. 2006;77:696-711.

Bledsoe JM, Johnston BD. Preparing families for international adoption. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:242-250.

Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees. JAMA. 2005;293:2501-2515.

Landgren M, Gronlund MA, Elfstrand PO, et al. Health before and after adoption from Eastern Europe. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:720-725.

Miller LC. International adoption: infectious diseases issues. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:286-293.

Schulte EE, Springer SH. Health care in the first year after international adoption. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1331-1349.

Trehan I, Meinzen-Der JK, Jamison L, et al. Tuberculosis screening in internationally adopted children: the need for initial and repeat testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e7-e14.

Van Londen WM, Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. Attachment, cognitive, and motor development in adopted children: short-term outcomes after international adoption. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1249-1258.

34.1 Medical Evaluation of Immigrant (Foreign-Born) Children for Infectious Diseases

Infectious diseases are among the most common medical diagnoses identified in immigrant children after arrival in the USA. Children may be asymptomatic; therefore, diagnoses must be made by screening tests in addition to history and physical examination. Because of inconsistent perinatal screening for hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses, syphilis, and HIV and the high prevalence of certain intestinal parasites and tuberculosis, all foreign-born children should be screened for these infections on arrival in the USA. Suggested screening tests for infectious diseases are listed in Table 34-2. In addition to these infections, other medical and developmental issues, including hearing, vision, dental, and mental health assessments; evaluation of growth and development; nutritional assessment; lead exposure risk; complete blood cell count with red blood cell indices; microscopic urinalysis; newborn screening (this could be done in non-neonates, too) and/or measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration; and examination for congenital anomalies (including fetal alcohol syndrome) should be considered as part of the initial evaluation of any immigrant child.

Commonly Encountered Infections

Intestinal Pathogens

The most common pathogens identified are Giardia lamblia (Chapter 274), Trichuris trichiura (Chapter 285), Hymenolepis species (Chapter 294), Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (Chapter 273), Schistosoma species (Chapter 292), Strongyloides stercoralis (Chapter 287), Ascaris lumbricoides (Chapter 283), and hookworm (Chapter 284). All nonpregnant refugees over 2 yr of age coming from sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia should be presumptively treated with predeparture albendazole. Rates of intestinal helminth infections susceptible to albendazole (Ascaris, Trichuris, or hookworm) from these areas have decreased. Nonrefugee immigrants do not receive predeparture treatment.

Therapy for intestinal parasites will be successful, but complete eradication may not occur always. Therefore, repeat ova and parasite testing after treatment in children who remain symptomatic is important to ensure successful elimination of all parasites. A follow-up eosinophil count is also recommended 3-6 mo later, and if still elevated, further evaluation is warranted. In addition, testing stool specimens for Salmonella species (Chapter 190), Shigella species (Chapter 191), Campylobacter species (Chapter 194), and Escherichia coli O157:H7 (Chapter 192) should be considered in children with diarrhea, especially if stools are bloody.

Tuberculosis (Chapter 207)

Since 2007, TB Technical Instructions for Medical Evaluation of Aliens have required that children aged 2-14 yr undergo a TB skin test if they are medically screened in countries where the TB rate is 20 cases or more per 100,000 population. If the skin test is positive, a chest x-ray is required. If the chest x-ray suggests TB, cultures and three sputum smears are required, all before arrival in the USA. This requirement is being phased in over a number of years, and some countries with a case rate of 20 per 100,000 may not currently be screening children. Check with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine for latest information (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dq/technica.htm).

Other Infectious Diseases

In the USA, multiple outbreaks of measles have been reported in immigrant children, including those adopted from China, and in their U.S. contacts. Prospective parents traveling internationally to adopt children, as well as their household contacts, should ensure that they have a history of natural disease or have been adequately immunized for measles according to U.S. guidelines. All people born after 1957 should receive 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine in the absence of documented measles infection or contraindication to the vaccine. Susceptible immigrant children and their families should be immunized as soon as possible after arrival according to recommended childhood, adolescent, and adult immunization schedules (Chapter 238).

Immunizations

Some immigrants will have written documentation of immunizations received in their birth or home country. Although immunizations such as BCG, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, and pertussis (DTP), poliovirus, measles, and hepatitis B virus vaccines often are documented, other immunizations, such as Haemophilus influenzae type b, mumps, and rubella vaccines, are given less frequently; and Streptococcus pneumoniae, human papillomavirus, meningococcal, and varicella vaccines are given rarely. Immigrant children and adolescents should receive immunizations according to the recommended schedules in the USA for healthy children and adolescents (Chapter 165). Although some vaccines with inadequate potency are used in other countries, most vaccines available worldwide are produced with adequate quality control standards and are reliable. Written documentation of immunizations can usually be accepted as evidence of adequacy of previous immunization if the vaccines, dates of administration, number of doses, intervals between doses, and age of the child at the time of immunization are consistent internally and comparable to current U.S. or World Health Organization schedules. Given the limited data available regarding verification of immunization records from other countries, measurements of serum antibodies to vaccine antigens is an option to ensure that vaccines were given and were immunogenic. An equally acceptable alternative when doubt exists is to reimmunize the child. Because the rate of more serious local reactions after diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine increases with the number of doses administered, serologic testing for antibody to tetanus and diphtheria toxins before reimmunizing or if a serious reaction occurs can decrease risk.

Canadian Paediatric Society. Children and youth new to Canada: health care guide. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Paediatric Society; 1999.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ health (website). wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel. Accessed March 12, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection among refugees arriving in the United States, 1979–1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:784-786.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendation regarding screening of refugee children for treponemal infection. MMWR. 2005;54(37):933-934.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection-United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:RR-15. 49–55

Chaudhary RK, Nicholls ES, Kennedy DA. Prevalence of hepatitis B markers in Indochinese refugees. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;125:1243-1246.

Connell TG, Ritz N, Paxton GA, et al. A three-way comparison of tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB Gold and T-SPOT.TB in children. PLoS One. 2008 Jul 9;3(7):e2624.

Hymas KC. Risks of chronicity following acute hepatitis B virus infection: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(4):992-1000.

Kim YJ, Nutman TB. Eosinophilia. In: Walker PF, Barnett ED, editors. Immigrant medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007:309-319.

Koff RS. Hepatitis B and hepatitis D. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR, editors. Infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2004:765-784.

Lifson AR, Thai D, O’Fallon A, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis, hepatitis B virus, and intestinal parasitic infections among refugees to Minnesota. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:69-77.

Minnesota Department of Health. Refugee health statistics (website). www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/refugee/stats/index.html. Accessed March 12, 2010

Rao MR, Naficy AB, Darwish MA, et al. Further evidence for the association of hepatitis C infection with parenteral schistosomiasis treatment in Egypt. BMC Infect Dis. 2002;2:29.

Recommendations and Guidelines. Advisory committee on immunization practices (website). www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/default.htm. Accessed March 12, 2010

Stadler LP, Mezoff AG, Staat MA, et al. Hepatitis B virus screening for internationally adopted children. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1223-1228.

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dq/technica.htm.

United States Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review. Statistics and publications: annual immigration statistics (website). www.usdoj.gov/eoir/statspub.htm.