Chapter 113 Adolescent Rape

Epidemiology

Some adolescents are at higher risk of being victims of rape than others (Table 113-1).

Table 113-1 ADOLESCENTS AT HIGH RISK OF RAPE VICTIMIZATION

MALE AND FEMALE ADOLESCENTS

Drug and alcohol use

Runaways

Intellectual disability or developmental delay

Street youths

Youths with a parental history of sexual abuse

PRIMARILY FEMALES

Survivors of prior sexual assault

Newcomers to a town or college

PRIMARILY MALES

Institutionalized settings (detention centers, prison)

Young male homosexuals

Types of Rape

Date rape (by a person dating the victim) is often drug facilitated and is prevalent in adolescent populations. Date rape drugs are pharmaceuticals administered in a clandestine manner to potential victims. γ-Hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), and ketamine hydrochloride are the leading agents used for these illegal purposes (Chapter 108). The pharmacologic properties of these drugs make them suitable for this use as they have simple modes of administration, are easily concealed (colorless, odorless, tasteless), have rapid onsets of action with resulting induction of anterograde amnesia, and have rapid eliminations due to short half-lives. Detection of these drugs requires a high index of suspicion and medical evaluation within 8-12 hr, prompting specific testing because routine toxicology screening is insufficient.

Male rape generally refers to same-sex rape of male teens by other males. Specific subgroups of young men are at high risk of being victims of rape (see Table 113-1). Male rape is most prevalent within institutional settings. Male rape that occurs outside of institutional settings typically involves coercion of the male teen by someone considered an authority figure, either male or female. Male rape victims often experience conflicted sexual identity whether or not they are homosexual. Issues of loss of control and powerlessness are particularly bothersome for male rape victims, and these young men commonly have symptoms of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and suicidal ideation. Males are less likely than females to report rape and less likely to seek professional help.

Laboratory Data

The forensic evidence kit should be completed when clinically indicated and if the patient is evaluated within 72 hr of sexual assault. Additional laboratory studies required during initial evaluation are noted in Table 113-2. Follow-up evaluations should be scheduled to repeat these laboratory studies.

Table 113-2 LABORATORY DATA FOR EVALUATION OF RAPE VICTIMS

WITHIN 8-12 HR (IF INDICATED BY HISTORY)

Urine and blood for date rape drugs (GHB, Rohypnol, and ketamine)

WITHIN 72 HR

Forensic evidence kit

Urinalysis

Pregnancy test

Hepatitis B screen

Syphilis (RPR, VDRL)

Herpes simplex virus titers (I & II)

HIV

Wet mount for the detection of spermatozoa, Trichomonas vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis

Cultures obtained based on history of physical contact for:

Oropharynx: Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Rectal: N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

Urethral (male): N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

Endocervical (female): N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

GHB, γ-hydroxybutyric acid; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Treatment

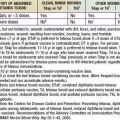

Medical treatment includes prophylaxis treatment for STIs (Chapter 114) and emergency contraception (Chapter 111.5). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the risk for acquiring STIs following a sexual assault in adults is 6-12% for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, 4-17% for Chlamydia trachomatis, and 0.5-3.0% for syphilis. Antimicrobial prophylaxis is recommended for adolescent rape victims due to the risk of acquiring an STI and the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (Table 113-3). HIV postexposure prophylaxis should be considered and consultation with an infectious disease specialist sought if higher transmission risk factors are identified (e.g., knowing that the perpetrator is HIV-positive, significant mucosal injury of the victim) to prescribe a triple antiretroviral regimen. Clinicians should review the importance for patient’s compliance with medical and psychological treatment and follow-up.

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae* |

* Prophylaxis is recommended for all three STIs.

† HIV postexposure prophylaxis is provided for patients with penetration and when the assailant is known to be HIV positive or at high risk due to a history of incarceration, intravenous drug use, or multiple sexual partners. If provided, follow-up must be arranged.

‡ Provided for patients with negative urine pregnancy screen. In addition, provide antiemetic (Compazine, Zofran) for patients receiving emergency contraception medication other than Plan B.

Bach PB. Gardasil: from bench, to bedside, to blunder. Lancet. 2010;375:963-964.

Blythe MJ, Fortenberry JD, Temkit M, et al. Incidence and correlates of unwanted sex in relationships of middle and late adolescent women. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:591-595.

Buzi RS, Tortolero SR, Ross MW, et al. The impact of a history of sexual abuse on high-risk sexual behaviors among females attending alternative schools. Adolescence. 2003;38:595-605.

Catalano SM. Criminal victimization 2006. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Discordant results from reverse sequence syphilis screening—five laboratories, United States, 2006–2010. MMWR. 2011;60(5):133-137.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases. Treatment guidelines 2010

Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Greene WF, et al. The safe dates program: 1-year follow-up results. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1619-1622.

Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Albero G. Male circumcision and HPV transmission to female partners. Lancet. 2011;377:183-184.

Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in male. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401-411.

Irwin CEJr, Rickert VI. Coercive sexual experiences during adolescence and young adulthood: a public health problem. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:359-361.

Kalwij S, Macintosh M, Baraitser P. Screening and treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. BMJ. 2010;340:c1915.

Kaufman M. Committee on Adolescence: Care of the adolescent sexual assault victim. Pediatrics. 2008;122:462-470.

Lehrer JA, Lehrer VL, Lehrer EL, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for sexual victimization in college women in Chile. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2007;33:168-175.

Nofzigen S, Stein RE. To tell or not to tell: lifestyle impacts on whether adolescents tell about violent victimization. Violence Vict. 2006;21:371-382.

Rand MR. Criminal victimization survey, 2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; September 2009.

Sheringham J. Screening for chlamydia. BMJ. 2010;240:c1698.

Silverman JG, Raj A, Clements K. Dating violence and associated sexual risk and pregnancy among adolescent girls in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e220-e225.

Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, et al. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA. 2001;286:572-579.

Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ, et al. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-2):1-20.

Steiner B, Benner MT, Sondorp E, et al. Sexual violence in the protracted conflict of DRC programming for rape survivors in South Kivu. Confl Health. 2009;15(3):3.

Taylor CA, Sorenson SB. Injunctive social norms of adults regarding teen dating violence. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:468-479.

Trent M, Haggerty CL, Jennings JM, et al. Adverse adolescent reproductive health outcomes after pelvic inflammatory disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(1):49-54.