Chapter 112 Adolescent Pregnancy

Epidemiology

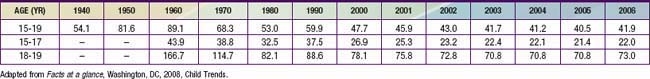

Before 2006, adolescent birthrates in the USA had steadily decreased since the early 1990s for all ages, races, and ethnic groups (Table 112-1), with the most dramatic decreases noted in African-American teens. In spite of the 3% increase from 2005 to 2006, the 2006 birthrate for teens ages 15-19 yr is considerably lower than the 1991 rate of 61.8. Pregnancy rates, which include births, miscarriages, stillbirths, and induced abortions, also decreased during this time frame, indicating that the decline in birthrates was not due to an increase in pregnancy terminations. The improvement in U.S. teen birthrates is attributed to 3 factors: more teens are delaying the onset of sexual intercourse, more teens are using some form of contraception when they begin to have sexual intercourse, and there is increased use of the new, long-lasting hormonal contraceptives.

Diagnosis (Table 112-2)

Table 112-2 DIAGNOSIS OF PREGNANCY DATED FROM FIRST DAY OF LAST MENSTRUAL CYCLE

CLASSIC SYMPTOMS

Missed menses, breast tenderness, nipple sensitivity, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, abdominal and back pain, weight gain, urinary frequency

Teens may present with unrelated symptoms that enable them to visit the doctor and maintain confidentiality

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

Tests for human chorionic gonadotropin in urine or blood may be positive 7-10 days after fertilization, depending on sensitivity

Irregular menses make ovulation/fertilization difficult to predict. Home pregnancy tests have a high error rate.

PHYSICAL CHANGES

2-3 wk after implantation: cervical softening and cyanosis

8 wk: uterus size of orange

12 wk: uterus size of grapefruit and palpable suprapubically

20 wk: uterus at umbilicus

If physical findings are not consistent with dates, ultrasound will confirm

Pregnancy Counseling and Initial Management

After the diagnosis of pregnancy is made, it is important to begin addressing the psychosocial, as well as the medical, aspects of the pregnancy. The patient’s response to the pregnancy should be assessed and her emotional issues addressed. It should not be assumed that the pregnancy was unintended. Discussion of the patient’s options should be initiated. These options include (1) releasing the child to an adoptive family, (2) electively terminating the pregnancy, or (3) raising the child herself with the help of family, father, friends, and/or other social resources. Options should be presented in a supportive, informative, nonjudgmental fashion; they may need to be discussed over several visits for some young women. Physicians who are uncomfortable in presenting options to their young patients should refer their patients to a provider who can provide this service expeditiously. Pregnancy terminations implemented early in the pregnancy are generally less risky and less expensive than those initiated later. Other issues that may need discussion are how to inform and involve the patient’s parents and the father of the infant; implementing strategies for insuring continuation of the young mother’s education; discontinuation of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use; discontinuance and avoidance of any medications that may be considered teratogenic; starting folic acid, calcium, and iron supplements; proper nutrition, and testing for STIs. Especially in younger adolescents, the possibility of coercive sex (Chapter 113) should be considered and appropriate social work/legal referrals made if abuse has occurred, though most pregnancies are not a result of coercive sex. Patients who elect to continue their pregnancies should be referred as soon as possible to an adolescent-friendly obstetric provider.

Characteristics of Teen Parents

Teenage men who become fathers as adolescents also have poorer educational achievement than their age-matched peers. They are more likely than peers to have been involved with illegal activities and with the use of illegal substances. Adult men who father the children of teen mothers are poorer and educationally less advanced than their age-matched peers and tend to be 2-3 yr older than the mother; any combination of age differences may exist. Younger teen mothers are more likely to have a greater age difference between themselves and the father of their child, raising the issue of coercive sex or statutory rape (Chapter 113).

Medical Complications of Mothers and Babies

Many young women who become pregnant have been exposed to violence or abuse in some form during their lives. There is some evidence that teenage women have the highest rates of violence during pregnancy of any group. Violence has been associated with injuries and death as well as preterm births, low birthweight, bleeding, substance abuse, and late entrance into prenatal care. An analysis of the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System indicates that from 1991 to 1999, homicide was the 2nd leading cause of injury-related deaths in pregnant and postpartum women. Women ages 19 yr and younger had the highest pregnancy-related homicide rate (Chapter 107).

Prematurity and low birthweight increase the perinatal morbidity and mortality for infants of teen mothers. These infants also have higher than average rates of sudden infant death syndrome (Chapter 367), possibly because of less use of the supine sleep position, and are at higher risk of both intentional and unintentional injury (Chapter 37). One study shows the risk of homicide to be 9 to 10 times higher if a child born to a teen mother is not the mother’s firstborn as compared with the risk to a firstborn of a woman age 25 yr or older. The perpetrator is often the father, stepfather, or boyfriend of the mother.

Psychosocial Outcomes/Risks for Mother and Child

Educational

Teenage mothers often do poorly in school and drop out prior to becoming pregnant. After childbirth many choose to defer completion of their education for some time. High school graduation or an equivalency degree is generally achieved eventually. Mothers who have given birth as teens generally remain 2 yr behind their age-matched peers in formal educational attainment at least through their 3rd decade. Maternal lack of education limits the income of many of these young families (Chapter 1).

Repeat Pregnancy

Approximately 20% of all births to adolescent mothers (15-19 yr) are second order or higher. Prenatal care is begun even later with a 2nd pregnancy, and the 2nd infant is at higher risk of poor outcome than the 1st birth. Mothers at risk of early repeat pregnancy include those who do not initiate long-acting contraceptives after the index birth, those who do not return to school within 6 mo of the index birth, those who are married or living with the infant’s father, or those who are no longer involved with the baby’s father and who meet a new boyfriend who wants to have a child. To reduce repeat pregnancy rates in these teens, programs must be tailored for this population, preferably offering comprehensive health care for both the young mother and her child (Table 112-3).

Table 112-3 2001 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS POLICY STATEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CARE OF ADOLESCENT PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN

| Create a medical home for adolescent parents and their children |

From Beers LAS, Hollo RE: Approaching the adolescent-headed family: a review of teen parenting, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 39:215–234, 2009.

Beers LAS, Hollo RE. Approaching the adolescent-headed family: a review of teen parenting. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2009;39:215-234.

Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, et al. Homicide: a leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:471-477.

Child Trends. Facts at a glance. Menlo Park, CA: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation; July 2008.

Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, et al. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113:320-327.

Hoffman SD, Maynard RA, editors. Kids having kids: economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy, ed 2, Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 2008.

Kohler PK, Manhart LE, Lafferty WE. Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:344-351.

Meade CS, Kershaw TS. The intergenerational cycle of teenage motherhood: an ecological approach. Health Psychol. 2008;27:419-429.

Rosengard C. Confronting the intendedness of adolescent rapid repeat pregnancy. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:5-6.

Shearer DL, Gyaben SL, Gallagher KM, et al. Selecting, implementing, and evaluating teen pregnancy prevention interventions: lessons from the CDC’s community coalition partnership programs for the prevention of teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:S42-S54.