chapter 56 Adolescent health and development

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

The essence of good adolescent healthcare consists of:

While young people are often considered a relatively healthy population group, current indices are poor for at least 20–30% of young people. Their health problems are mainly psychosocial and, certainly in clinical settings, likely to be overlooked. Young people are notoriously reluctant to seek services to address these social and psychological self-concerns.1,2 They are also involved in health risk behaviours earlier than in past generations. Many engage in behaviour that threatens their health and wellbeing, and there is increasing evidence that many problem behaviours in young people are interrelated. Young people with conduct disorders, for example, are also likely to engage in tobacco, alcohol and substance use, to engage in high-risk sexual behaviour and to experience academic failure.3

NORMAL ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT

Adolescence has been described as:

a period of personal development during which a young person must establish a sense of individual identity and feelings of self-worth which include an alteration of his or her body image, adaptation to more mature intellectual abilities, adjustments to society’s demands for behavioural maturity, internalising a personal value system, and preparing for adult roles.4

Adolescence begins with the onset of puberty and ends with the acquisition of adult roles and responsibilities. It is characterised by rapid change in the following domains:5

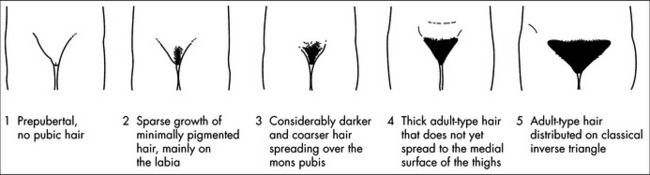

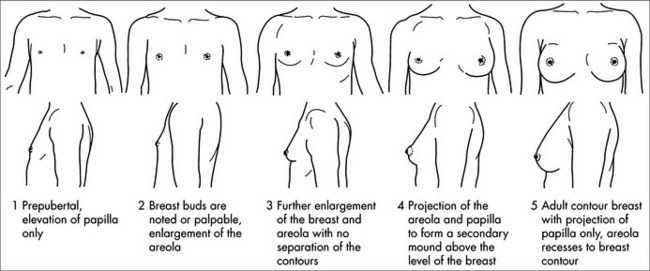

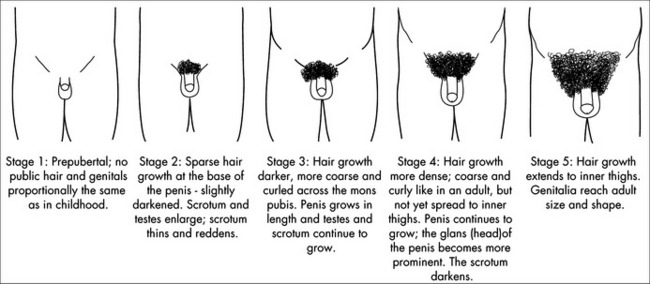

THE EXPERIENCE OF PUBERTY

The classic milestones of puberty are determined by Tanner’s sex maturity ratings. Tanner’s staging system is based on breast, genital and pubic hair changes, with Stage 1 being prepubertal and Stage 5 adult (Figs 56.1, 56.2 and 56.3).6 In girls, peak height velocity usually occurs at Stage 2–3 (around 12 years) and menarche (initiation of menstruation) at Stage 4. In boys, peak height velocity occurs at Stage 3–4 (14 years) and semenarche (initial ejaculation) at Stage 3.

The psychosocial impact of the timing of puberty affects girls and boys differently.

For those who mature earlier than average:

A SNAPSHOT OF HEALTH ISSUES IN ADOLESCENCE7

Adolescent health is, ideally, understood via the dual concepts of health and wellbeing. It is estimated that approximately 75% of deaths among young people in developed countries are from preventable causes, mostly non-intentional injury. Drug-related deaths account for almost 25% of all deaths among young people, and youth suicide is another major cause of mortality. Young people are experiencing mental health problems at higher rates than older age groups and retaining their increased risk beyond youth into older age8—at any one time, up to 20% of young people will suffer from a mental disorder. Together, mental health and behavioural disorders account for more than half of all afflictions affecting adolescents. Poor nutrition is now also coming to be recognised as a significant risk factor for poor mental health in adolescents.9

Sexual health is another important and challenging issue. The number of notifications for chlamydia among 15–24 year olds has increased by more than 300% between 1999 (when national data have been available) and 2008. Young people, especially young women, are more likely to contract STIs and, while rates of teenage childbirth have declined in recent decades, teenage pregnancy remains a major adolescent health concern in developed nations. Restricting our focus to these biological indicators alone, however, ignores the complex, dynamic contexts in which sexuality is being experienced by young people.

THE CLINICAL CONSULTATION

Many healthcare professionals feel ill-equipped to deal with young people in their practices, particularly in relation to sexuality and substance use.2 Young people want to address health behaviours with their doctor but often feel too embarrassed to initiate discussion in these sensitive areas. And while parents also want clinicians to discuss a broad range of health issues with their adolescent children, many fail to do so.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS WITH YOUNG PEOPLE

Confidentiality

Acknowledge feelings that may hinder communication

Culturally sensitive communication

In exploring cultural issues around diagnosis and treatment:10

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL HISTORY AND RISK ASSESSMENT: HEEADSSS

The psychosocial history/risk assessment is the cornerstone of a comprehensive adolescent health assessment and is at the heart of integrative adolescent healthcare.11 It recognises that adolescent health and wellbeing are mostly influenced by psychosocial and behavioural factors, provides a profile of risk and protective factors that can guide intervention, and also facilitates the development of rapport and trust.

A ‘HEEADSSS screen’ is one of the recommendations of the RACGP for preventive care among adolescents:12

Simple examples of questions in each domain are given in Table 56.3. For a more comprehensive guide to using HEEADSSS, refer to Goldenring and Rosen.11

| Domain | Questions | Risk/Protective |

|---|---|---|

| Home |

WRAPPING UP THE CONSULTATION

ENGAGING THE FAMILY

Engaging the family and gaining the trust of parents is critical in treating young people. In many cultures, participation in healthcare is a family responsibility rather than an individual responsibility.13

LEGAL ISSUES

Even within countries, different state jurisdictions may allow for different legal rights and obligations in relation to medical consultations and mandatory notification by healthcare professionals about issues such as ‘children at risk of harm’ or the reporting of notifiable diseases. Confidentiality is also a legal requirement in many countries.

Common law allows for the recognition of the ‘mature minor’ in many countries, a legal concept that arose in the United Kingdom in the 1980s in Gillick vs West Norfolk A.H.A. [1984] 1 QB581. This process requires a clinical judgment about the young person’s ‘intelligence and understanding, to enable full understanding of what is proposed’; this is sometimes referred to the ‘Gillick test’.14

beyondblue, National Depression Initiative (advice for parents). http://www.beyondblue.org.au.

Getontop, guide to mental health for teenagers. http://www.getontop.org.

Headroom, information on mental health for teenagers, parents and friends. http://www.headroom.net.au.

Kids’ helpline. http://www.kidshelp.com.au.

Lifeline. http://www.lifeline.org.au.

ReachOut (advice for teenagers). http://www.reachout.com.au.

Not So Straight. http://www.notsostraight.com.au.

http://www.yoursexhealth.org. (young people’s sexuality and sexual health)

1 Kang M, Sanci LA. Primary healthcare for young people in Australia. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;9(3):229-234.

2 Booth M, Bernard D, Quine S, et al. Access to healthcare among Australian adolescents: young people’s perspectives and their socioeconomic distribution. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:97-103.

3 Ary D. Development of adolescent problem behaviour. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1999;27(2):141-150.

4 Ingersoll GM. Adolescents. 2nd edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989.

5 Bennett DL, Kang M. Adolescence. In: Oates K, Currow K, Hu W, editors. Child health: a practical manual for general practice. Sydney: MacLennan & Petty, 2001. Ch 12

6 Bennett DL, Kang M, Leu-Marshall E. Adolescent health. Check program of self-assessment. Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2006.

7 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Young Australians: their health and wellbeing. AIHW Cat. No. PHE 87. Canberra: AIHW, 2007.

8 Eckersley RM. The health and well-being of young Australians: present patterns, future challenges. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;9(3):217-227.

9 Jacka FN, Kremer PJ, Leslie ER, et al. Associations between diet quality and depressed mood in adolescents: results from the Australian Healthy Neighbourhoods Study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010;44(5):435-442.

10 Bennett DL, Chown P, Kang M. Cultural diversity in adolescent healthcare. Med J Aust. 2005;183(8):436-438.

11 Goldenring JM, Rosen DS. Getting into adolescent heads: an essential update. Contemp Pediatr. 2004;21:64.

12 Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. 7th edn. Melbourne, Australia: RACGP, 2009.

13 Reidpath D, Allotey P. Multicultural issues in general practice. Curr Ther. 1999/2000;40(12):35-37.

14 Bird S. Children and adolescents: who can give consent? Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(3):165-166.