Adhesiolysis

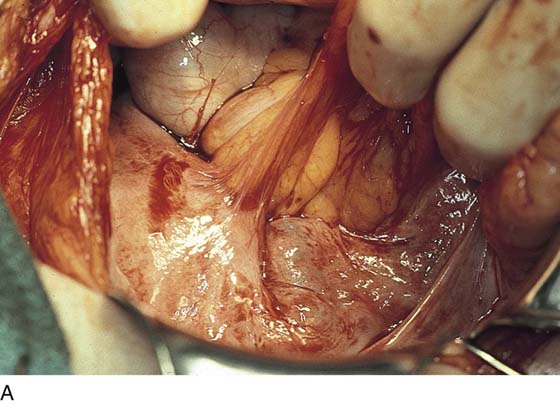

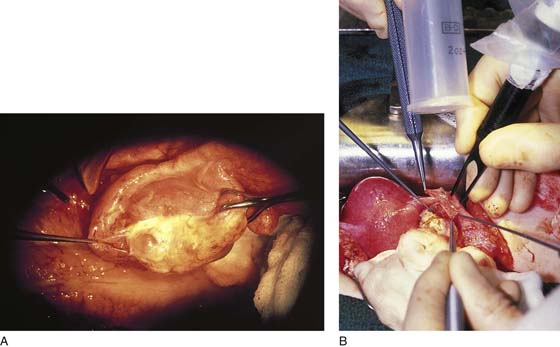

Adhesions create anatomic difficulties because they blur normal tissue planes and boundaries. Adhesions may range from thin and filmy to thick and fleshy. Fibrosis may simply agglutinate one structure to another. The key points in separating adhesions are to utilize sharp dissection whenever possible and to avoid blunt dissection, because the latter frequently results in the tearing of one or both adhesed structures during dissection (e.g., when separating adhesed intestine from the uterus, it is better to err in the direction of leaving extra tissue attached to the bowel and to dissect closer to the uterus) (Fig. 24–1A–E). The author avoids energy sources when the adhesions are proximate to bowel, bladder, ureter, or larger blood vessels. The initial cut should attempt to reverse the original attachment sequence rather than create new tissue planes.

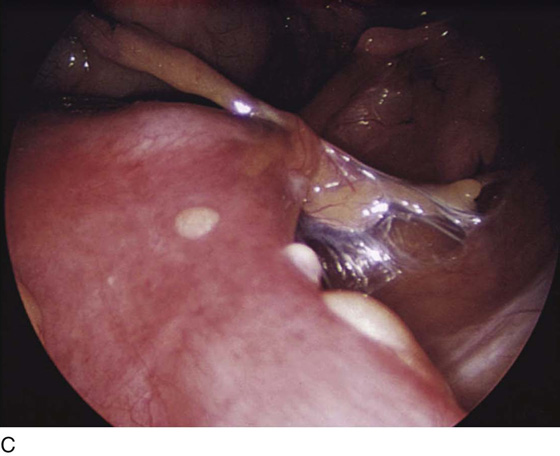

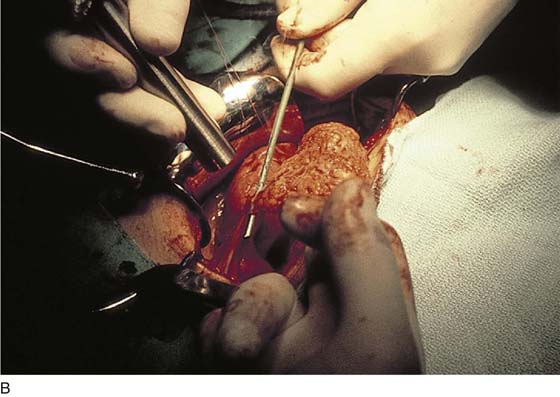

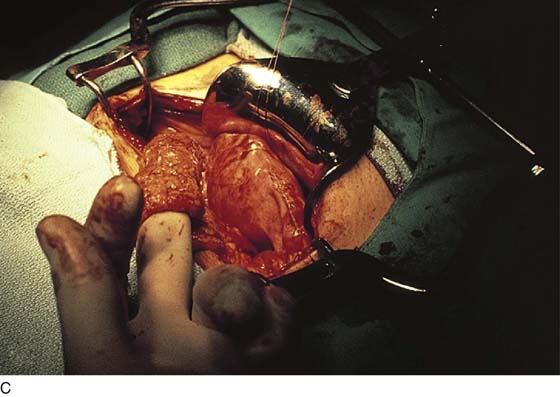

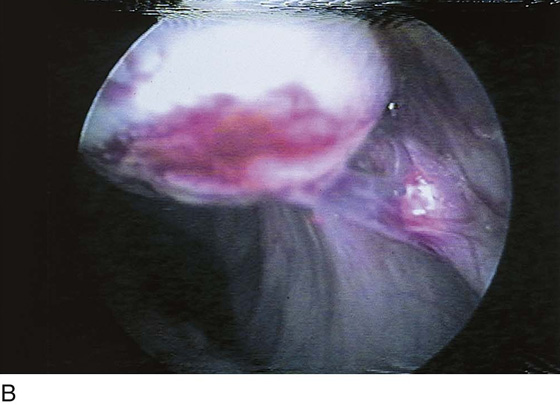

Careful and detailed inspection of visceral structures closely involved in adhesiolysis surgery is vitally important to avoid missing an iatrogenic bowel or bladder, or ureteral injury. Tubo-ovarian adhesiolysis may require magnification to avert heavy, obscuring hemorrhage. In this location, carbon dioxide (CO2) laser and bipolar electrosurgery are vital tools to prevent or reduce bleeding (Fig. 24–2A–C).

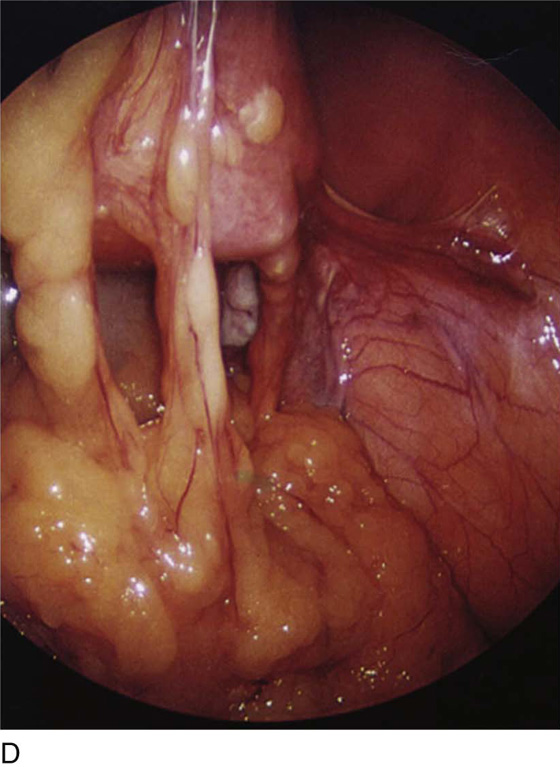

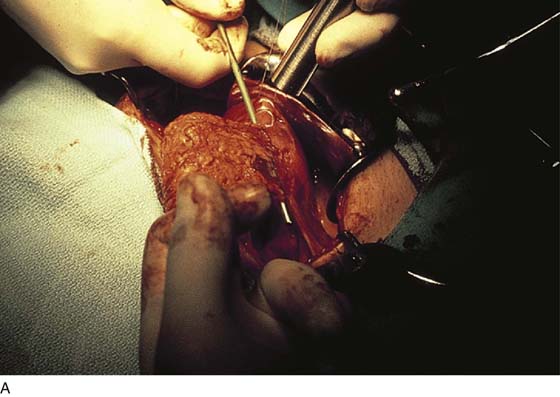

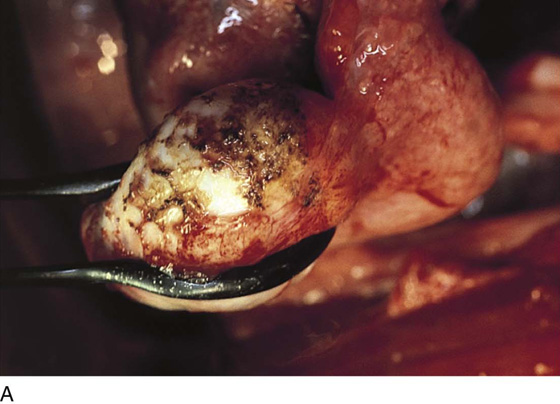

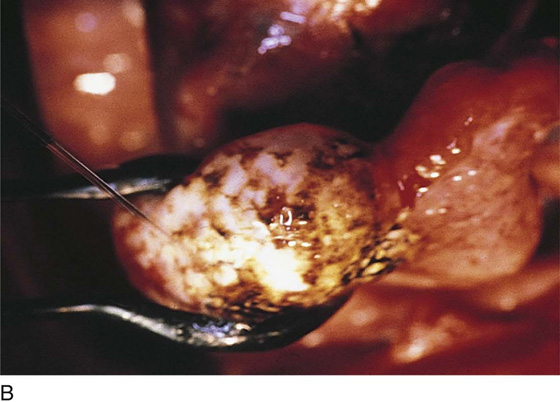

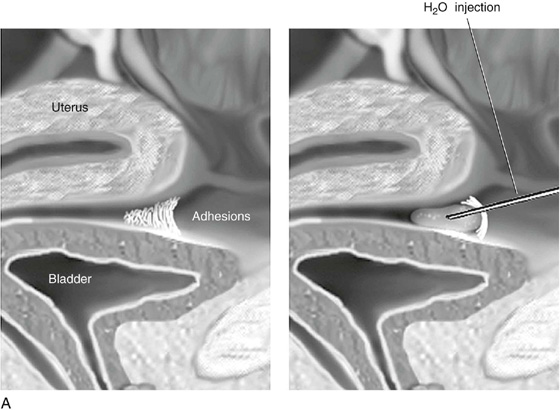

Adhesions covering or enveloping the ovary are better treated by careful laser vaporization rather than by sharp dissection (Fig. 24–3A–C). Omental adhesions may require the omentum to be doubly clamped, cut, and suture-ligated to facilitate takedown. Sidewall adhesions deserve some special considerations. Ovary and tube may be “plastered” to the pelvic peritoneum (Fig. 24–4A, B). The surgeon must identify the anatomy behind the adhesions. In this instance, entry into the retroperitoneal space facilitates identification. The external iliac vein, hypogastric artery and vein, ureter, and ovarian vessels must be identified and secured from injury during adhesiolysis. Injection of sterile water with a fine needle may facilitate the development of a safe dissection plane between adhesions involving the bladder, bowel, and sidewall structure (Fig. 24–5A–D).

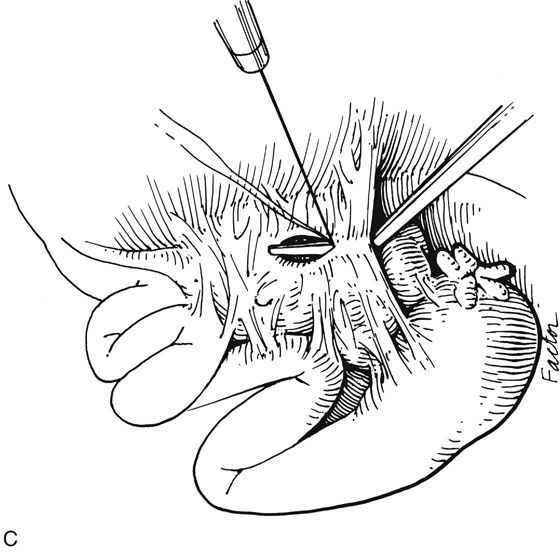

Adhesiolysis cannot be optimally accomplished without the use of traction and countertraction (see Fig. 24–5). The latter technique helps the clinician to identify the plane of attachment of the adhesion to a visceral structure and in turn permits the least bloody and least traumatic separation. Adhesions are obviously always best dissected from superficial (first cut) to deep (last cut). Similarly, the tip of the scissors must always be in view. If an energy device (e.g., a CO2 laser) is to be used, a backstop should be placed behind the adhesion. Similarly, in this circumstance, water can serve as a backstop because it will absorb laser light (Fig. 24–6A–J).

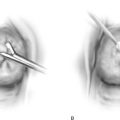

The technique used by the author for adhesions that are layered consists of making a small, careful nick at the edge of the adhesion, insinuating a fine dissection scissors into the adhesion, and alternately spreading and closing the scissors blade to expose any structure within the adhesion before cutting it. This can also be done with a laser coupled to an adjustable backstop (Fig. 24–7). In this manner, a plane of safe dissection is established, allowing the adhesions to be transected sharply. Similarly, one can use a Touhy needle (18 or 22 gauge) to inject saline into the adhesion to facilitate separation.

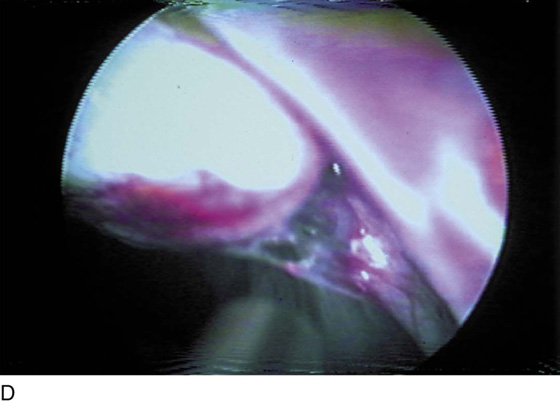

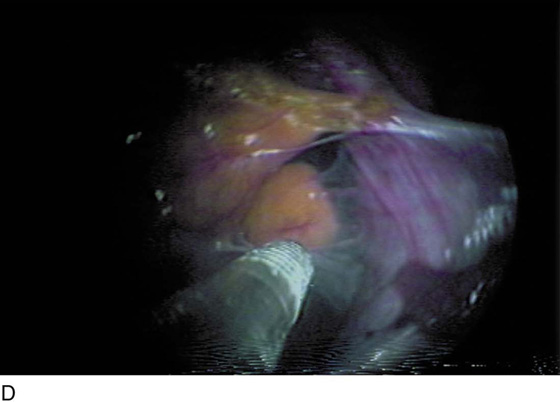

FIGURE 24–1 A. Typical adhesions formed between the sigmoid colon and uterus, as well as between the small bowel and uterus. Note that traction produced by the surgeon’s hand clearly demonstrates the attachments of the adhesions, as well as their vascularity. B. A thick adhesion is clearly visible in this picture. When cut, this type of adhesion may bleed because of the infiltration of parasitic and thin-walled blood vessels. C. Filmy and vascularized adhesions between the uterine fundus and the small intestine. D. Extensive vascularized adhesions between the posterior surface of the uterus and the colon. E. Close-up of fleshy adhesions between the uterus and the sigmoid colon.

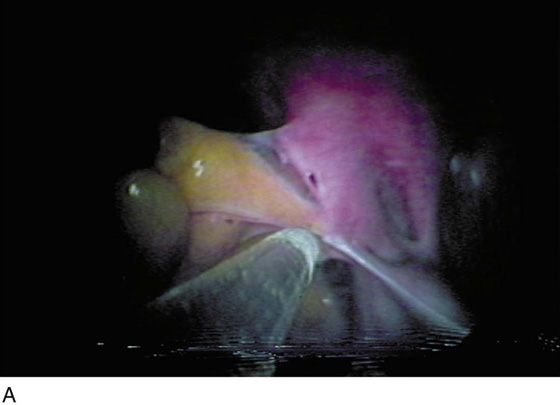

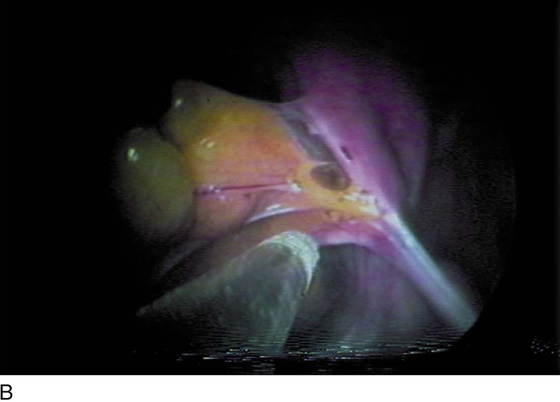

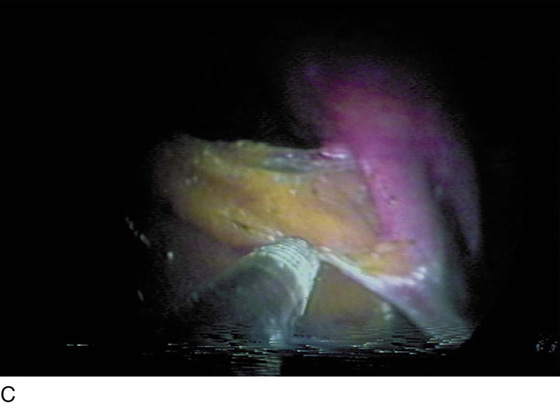

FIGURE 24–2 A. Omentum-to-uterus adhesion has been placed in traction and backstopped with a metal probe. B. The adhesion is divided with use of the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. The underlying colon is protected from laser beam injury by the backstop. C. The adhesed omentum has been neatly and atraumatically separated.

FIGURE 24–3 A. Encapsulation of the ovary by adhesions is best dealt with by tightly controlled carbon dioxide (CO2) laser vaporization. B. Vaporization of the adhesion is virtually complete. Note that this technique preserves the (white) capsule of the ovary. A jet of the irrigation stream is seen as char is washed away. C. Larger pieces of the vaporized adhesions are debrided with a moistened cotton-tipped applicator.

FIGURE 24–4 A. Dense tubo-ovarian adhesions are best lysed by injecting sterile water or saline beneath the adhesions to develop a plane for dissection. B. An energy device may be used, but it must be capable of fine incisions and minimal thermal spread. Alternatively, sharp dissection with fine scissors and fine suture-ligature to control bleeding may be used.

FIGURE 24–5 A. Sterile water is injected between dense uterine and urinary bladder adhesions to provide both a plane of dissection and a heat sink. B. The ovary is held down in its fossa by an adhesive band. C. Adhesions are cut between tube and ovary with a focused carbon dioxide (CO2) laser beam with a manipulating backstop in place. D. The CO2 laser sharply cuts the adhesion with the use of a wave guide inserted via the operating channel of the laparoscope.

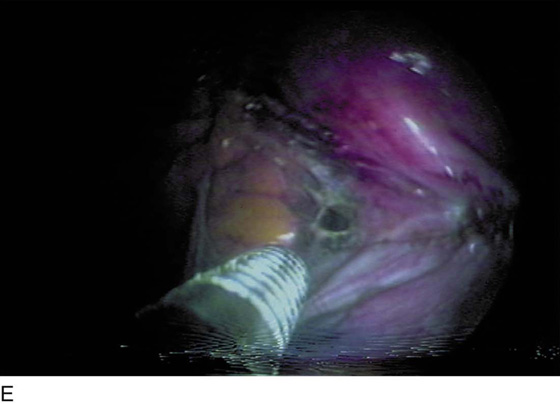

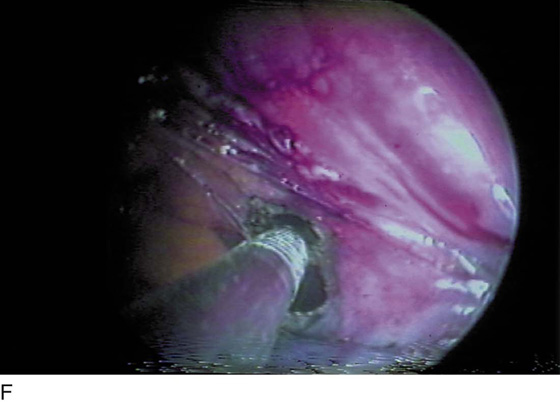

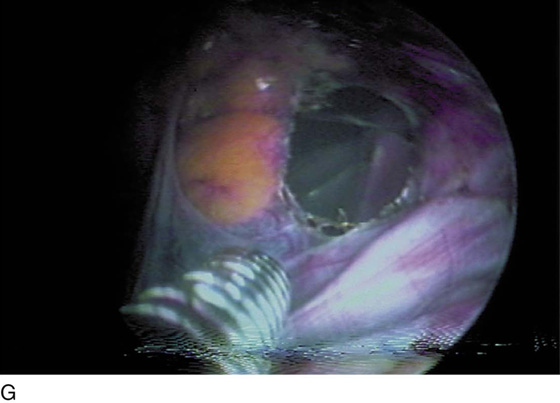

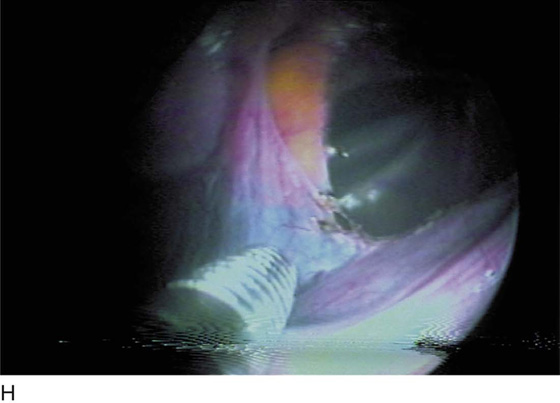

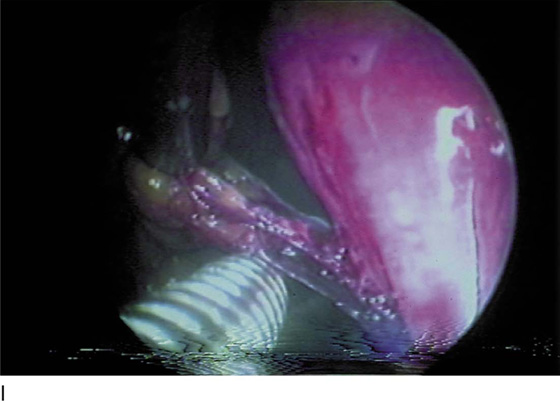

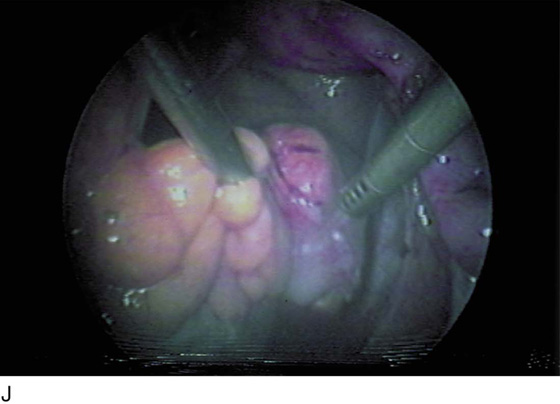

FIGURE 24–6 A. Layer adhesions are identified between the sigmoid colon and the lateral pelvic wall. The tube and the infundibulopelvic ligament are seen on the far right. Traction permits the surgeon to identify the plane of cleavage. B. Initial cuts are made by the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser beam, which is delivered by a wave guide (foreground). C. The adhesion (first layer) is cut close to the tube. D. A second layer of less dense adhesions is identified as the upper layer of adhesions is cut. E. The second layer is penetrated by the laser beam. The pelvic floor is protected by the infusion of water beneath the adhesions. F. A large hole is created in the adhesions as they are vaporized. G. The pelvic floor is viewed through the hole in the adhesion. H. The dissection is virtually complete. I. A final strand of an adhesion between the bowel and the bladder is cut. J. The sigmoid colon is completely free from the reproductive organs. The intestine and the uterus are awash in irrigation fluid.

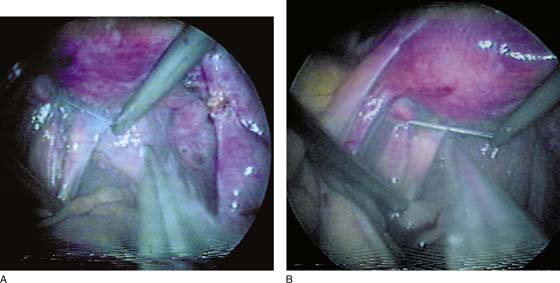

FIGURE 24–7 A. The posterior surface of the uterus is adhesed to the cul-de-sac. An adjustable backstop is placed behind the adhesions. B. The adhesions are sharply cut over the backstop.