9 Acute Respiratory Failure

Acute respiratory failure is one of the leading causes of admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). Behrendt et al. reported that the incidence of acute respiratory failure requiring hospitalization was 137 per 100,000 population in the United States, and the median age of the patients was 69 years.1 More recently, Ray et al. reported that 29% of patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) with acute respiratory failure require admission to an ICU.2

Causes of Hypoxic Respiratory Failure

Causes of Hypoxic Respiratory Failure

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Management

Management

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) and mechanical ventilation via an endotracheal tube are two approaches for providing supplemental oxygen and, at the same time, providing partial or total support for minute ventilation (i.e., decreasing the work of breathing). In hemodynamically stable patients with mild or moderate respiratory failure, NIPPV may decrease the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation and decrease the patient’s length of stay in the ICU.4,5 NIPPV should not be used in patients with altered mental status, who are unable to protect the airway, or for patients who are unable to clear secretions adequately. For some patients, tolerance for NIPPV can be improved by using a nasal mask and starting at a lower level of inspiratory pressure (5 cm H2O).

In cases of hypercarbic respiratory failure, the primary goal of treatment is to maintain arterial pH above 7.32 with a PaCO2 appropriate for the pH.6 In the absence of marked acidemia or hypoxemia, hypercarbia is well tolerated. Accordingly, it may be preferable under some circumstances to accept PaCO2 values that are abnormally high (e.g., >45 mm Hg) rather than risk damaging (or further damaging) the lungs with ventilator settings that promote excessive shear stress within the pulmonary parenchyma.

Intubation And Mechanical Ventilation

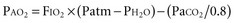

The need for mechanical ventilatory support is a clinical decision based on increased work of breathing (i.e., respiratory rate >35/min, use of accessory muscles of ventilation) and inability to clear secretions, and maintain a patent, protected, adequate airway. The clinician has only two basic maneuvers for improving PaO2 using mechanical ventilation. The first is to increase FIO2. The second is to increase mean airway pressure. The latter goal can be achieved primarily in two ways: (1) application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or (2) changing the duty cycle so that the duration of inspiration is longer (in the extreme, this maneuver is called inverse ratio ventilation). In patients with acute lung injury, tidal volume should be limited to 6 mL/kg (ideal body weight).7 Prone positioning, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, inhaled nitric oxide, differential lung ventilation, and transtracheal gas insufflation have been shown to improve arterial oxygenation in selected patients with profound hypoxemia due to acute lung injury, but none of these approaches has been shown to improve survival.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Mortality in patients with respiratory failure requiring positive pressure ventilatory support is dependent on the primary cause. The hospital mortality rate is 30% to 40%, and the 1-year mortality rate is 50% to 70%. Functional status deteriorates immediately after the illness and improves to baseline by 6 to 12 months in survivors.8

ARDSnet. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308.

First ROCT to show outcome benefit in ventilation strategy in patients with ARDS.

Behrendt CE. Acute respiratory failure in the United States: incidence and 31-day survival. Chest. 2000;118(4):1100-1105.

Provides excellent epidemiology data for acute respiratory failure in the United States.

Chelluri L. Critical illness in the elderly: review of pathophysiology of aging and outcome of intensive care. J Intensive Care Med. 2001;16:114-127.

Reviews specific factors affecting prognosis in the elderly.

Dakin J, Griffiths M. The pulmonary physician in critical care 1: pulmonary investigations for acute respiratory failure. Thorax. 2002;57:79-85.

Good review of bedside clinical evaluation tools in assessing etiology of acute respiratory failure.

Hill NS, Brennan J, Garpestad E, Nava S. Noninvasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(10):2402-2407.

Informative review of use of NIV for primarily medical causes of ARF.

Jaber S, Chanques G, Jung B. Postoperative noninvasive ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(2):453-461.

Discusses recent advances in use of NIPPV in postoperative patients with ARF.

MacIntyre N, Huang YC. Acute exacerbations and respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):530-535.

Reviews latest diagnostic, prognostic data and treatments for acute exacerbations of COPD.

Ray P, Birolleau S, Lefort Y, Becquemin MH, Beigelman C, Isnard R, et al. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly: etiology, emergency diagnosis and prognosis. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R82.

1 Behrendt CE. Acute respiratory failure in the United States: incidence and 31-day survival. Chest. 2000;118(4):1100-1105.

2 Ray P, Birolleau S, Lefort Y, Becquemin MH, Beigelman C, Isnard R, et al. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly: etiology, emergency diagnosis and prognosis. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R82.

3 Dakin J, Griffiths M. The pulmonary physician in critical care 1: Pulmonary investigations for acute respiratory failure. Thorax. 2002;57:79-85.

4 Hill NS, Brennan J, Garpestad E, Nava S. Noninvasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(10):2402-2407.

5 Jaber S, Chanques G, Jung B. Postoperative noninvasive ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(2):453-461.

6 MacIntyre N, Huang YC. Acute exacerbations and respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):530-535.

7 ARDSnet. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308.

8 Chelluri L. Critical illness in the elderly: Review of pathophysiology of aging and outcome of intensive care. J Intensive Care Med. 2001;16:114-127.

) mismatching. Hypoxia occurs as a result of

) mismatching. Hypoxia occurs as a result of  mismatching because of admixture of venous with arterial blood at the capillary level.

mismatching because of admixture of venous with arterial blood at the capillary level.  mismatching is the most common cause of hypoxia in hospitalized patients. In contrast to hypoxemia caused by an anatomic shunt, hypoxemia caused by

mismatching is the most common cause of hypoxia in hospitalized patients. In contrast to hypoxemia caused by an anatomic shunt, hypoxemia caused by  mismatching can be improved by administration of supplemental oxygen.

mismatching can be improved by administration of supplemental oxygen. mismatching is so severe that a portion of pulmonary arterial blood flows through lung regions with essentially no ventilation. Potential causes of this sort of physiologic shunting include pneumonia, lung contusion, or severe congestive heart failure. Oxygenation cannot be improved with supplemental oxygen in patients with a true right-to-left shunt, irrespective of whether the shunt is caused by an anatomic or a functional derangement.

mismatching is so severe that a portion of pulmonary arterial blood flows through lung regions with essentially no ventilation. Potential causes of this sort of physiologic shunting include pneumonia, lung contusion, or severe congestive heart failure. Oxygenation cannot be improved with supplemental oxygen in patients with a true right-to-left shunt, irrespective of whether the shunt is caused by an anatomic or a functional derangement.