Acute Pelvic Pain in Women

Perspective

Epidemiology

Over one third of reproductive-age women will experience nonmenstrual pelvic pain. Among diagnoses for women with pain caused by gynecologic disorders in the emergency department, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and lower genital tract infections (e.g., cervicitis, candidiasis, Bartholin’s abscess) account for almost half. Other common diagnoses are menstrual disorders, noninflammatory ovarian and tubal pathology (including cysts and torsion), and ectopic pregnancy. In the general population, ectopic pregnancy accounts for 2% of first-trimester pregnancies; however, among women visiting the emergency department with vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain in the first trimester of pregnancy, the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is as high as 18%.1

Younger patients and those with multiple sexual partners are more likely to have PID, and a previous episode increases the likelihood of a subsequent episode.2 The risk of ectopic pregnancy is higher in women who have had PID, pelvic surgery, or a prior ectopic pregnancy, as well as in women with an intrauterine device. Heterotopic pregnancy is of special concern in women undergoing fertility treatment. The incidence of heterotopic pregnancy in the general population was 1 in 30,000 patients in 1948 and is currently reported to be as high as 1 in 8000. It is much more common in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques (in vitro fertilization and ovulation-stimulating medications), with an incidence of 1 in 100.3 Common nongynecologic diseases, such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, urinary tract infection, and urolithiasis, remain important considerations in the woman with acute pelvic pain. Box 33-1 lists conditions accounting for pelvic pain in most women.

Some causes of pelvic pain may lead to serious sequelae. PID carries the short-term risk of tubo-ovarian abscess and the long-term risks of impaired fertility, chronic pelvic pain, and increased predisposition to ectopic pregnancy.5 Rupture of an ectopic pregnancy or a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst may be life-threatening. Unrecognized abuse may have serious or lethal consequences as well.

Diagnostic Approach

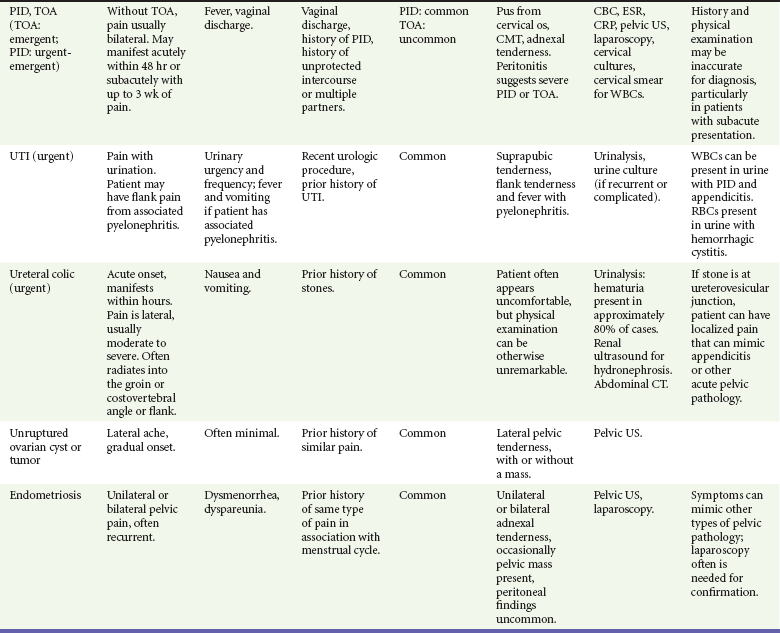

The differential diagnosis of pelvic pain is broad (see Box 33-1). Most causes of pelvic pain fit into three categories: (1) the reproductive tract, (2) the urinary tract, and (3) the intestinal tract. Because a subset of pelvic pain is found only in pregnancy, the pregnancy test is a key branch point in the diagnostic process. Potential pregnancy-related disorders can be divided into complications of early pregnancy and complications that occur further along in pregnancy. Although the specific cause of pelvic pain cannot always be determined at the initial ED visit, an organized approach usually leads to the confirmation or exclusion of disorders most likely to result in significant morbidity and/or mortality.

Pivotal Findings

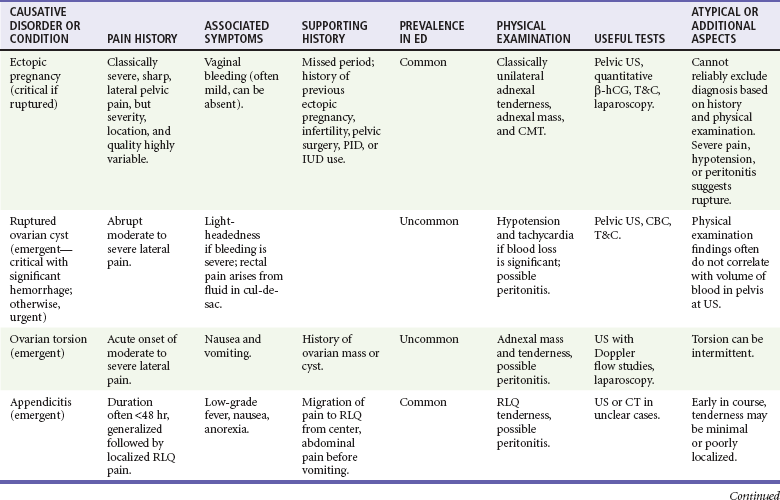

It is rare that any particular finding on history or physical examination (summarized in Table 33-1) is reliable enough to conclusively make or exclude a particular diagnosis, so ancillary testing (beyond a simple pregnancy test) is commonly required in the evaluation of patients with acute pelvic pain.

The bimanual examination may at times provide important information; however, findings on pelvic examination can be subjective and unreliable4,5 and may be most helpful to localize the process to one side or the other or to help focus the workup of the pathologic process to the reproductive organs.

Symptoms

The presence, quantity, and duration of associated vaginal bleeding should be ascertained. (See also Chapters 34 and 178.) In a nonpregnant patient, bleeding may be associated with PID, trauma, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, or cervical or uterine cancer. In a pregnant patient, bleeding may be associated with a subchorionic hemorrhage in an otherwise viable pregnancy, an ectopic pregnancy, a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) (which may continue to cause bleeding after expulsion of the uterine contents, especially if any products of conception are retained), or later in pregnancy with placenta previa or abruption. In some cases the amount of bleeding may be substantial enough to necessitate blood transfusion and surgical intervention.

Signs

The physical examination is directed toward the abdomen and pelvis. Pelvic examination is performed in virtually all patients, including pregnant patients at less than 20 weeks of gestation. Pregnant patients beyond 20 weeks of gestation with complaints of vaginal bleeding should undergo transabdominal pelvic ultrasound study for placental localization before the pelvic examination (see Chapter 178), have a fetal heart rate measured and documented, and may need a timely obstetric consultation.

Laboratory Tests and Imaging

Patients with a positive pregnancy test result should undergo a bedside ED ultrasound or formal ultrasound examination to evaluate for ectopic pregnancy.7 Identification of an IUP by ultrasound imaging excludes ectopic pregnancy with a high degree of certainty, as heterotopic pregnancy is exceedingly rare in patients who are not undergoing assisted reproduction. Conversely, a patient with a positive pregnancy test in whom a definite IUP cannot be seen is presumed to have an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise. In addition, the presence of a gestational sac alone is not enough to confirm an IUP; experienced sonographers can use the double decidual sign, but it is recommended that less experienced sonographers visualize a yolk sac or an embryo for definitive ultrasonographic confirmation of an IUP. A complex adnexal mass, tubal ring, extrauterine yolk sac or embryo, or free fluid is indicative of a probable ectopic pregnancy.6 The presence of free intra-abdominal fluid on ultrasound with a negative urine pregnancy test is consistent with hemorrhage or a ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. Regardless of cause, intra-abdominal free fluid is presumed to be blood and is addressed expediently.

Diagnostic Algorithm

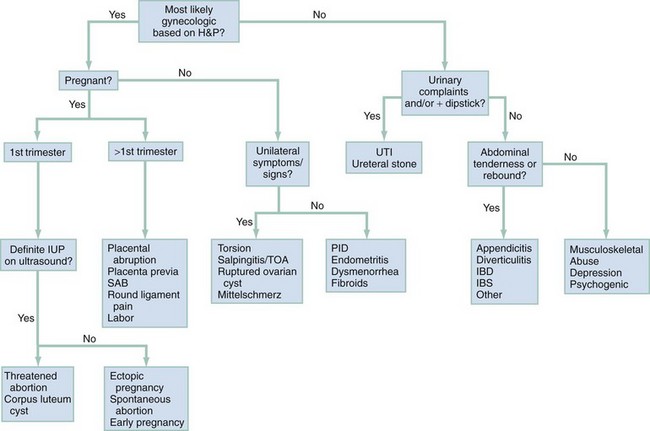

The algorithm in Figure 33-1 is designed to help focus further testing and progress to a rational provisional diagnosis. It is not unusual, however, for common diseases to manifest in uncommon ways or for more than one disease to be present, and tests are interpreted carefully in the context of the individual patient’s presentation. As examples, patients with a positive result on urinalysis testing may also have appendicitis, and pregnant patients may also have ovarian torsion. With certain diseases, such as endometriosis, definitive testing is not available in the ED, and the patient’s history may be the most important discriminator.

Nonpregnant patients with pain that seems to be gynecologic in nature should be assessed for hemorrhage from a ruptured ovarian cyst; for ovarian torsion (see Chapter 100); and for infection, including cervicitis, endometritis, PID, salpingitis, and tubo-ovarian abscess. Although the history and physical examination often are sufficient to diagnose infection, ultrasound assessment is helpful if torsion, tubo-ovarian abscess, or ruptured hemorrhagic cyst is suspected. Ultrasound findings also may support a diagnosis of PID if evidence of salpingitis is noted, or of a simple ruptured cyst if a characteristic ovarian appearance is combined with presence of a small amount of free fluid. Although not as reliable as CT scanning, ultrasound may be used to examine the appendix.

Because in practice it is difficult to differentiate some gynecologic origins of pain from classic intra-abdominal causes (such as right ovarian pathology from appendicitis), the workup may require an ultrasound study or a CT scan, or both. If the cause appears to be most likely gynecologic, then an ultrasound examination of the ovary and then the appendix is more reasonable, followed by a CT scan if the ultrasound findings are negative and the presentation is possibly consistent with appendicitis or other alternate diagnoses. Patients whose pain does not seem to be from the reproductive tract often have urinary infections or stones, abdominal sources of pain (see Chapter 27), musculoskeletal pathology, may be victims of abuse, or may have depression. Vascular causes of pain are possible but uncommon.

Empirical Management

An algorithm for management of patients with acute pelvic pain is presented in Figure 33-2. Patients who are in extremis are most likely to be hemorrhaging, although on occasion septic shock may be the cause. Ectopic pregnancy, placental abruption, and hemorrhagic ovarian cyst may cause life-threatening hemorrhage with no or minimal vaginal bleeding. Patients with these disorders need rapid treatment with fluid and blood products and may require surgical intervention before stabilization can be achieved. A bedside ultrasound may help the clinician reach the presumptive diagnosis expediently. Septic shock may be a consequence of abdominal or pelvic processes and may require both general surgical and gynecologic consultations, as well as admission to an intensive care setting.

References

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1479.

2. Beigi, RH, Wiesenfeld, HC. Pelvic inflammatory disease: New diagnostic criteria and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003;30:777.

3. Rabbani, I, Polson, DW. Heterotopic pregnancy is not rare: A case report and literature review. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25:204.

4. Close, RJ, Sachs, CJ, Dyne, PL. Reliability of bimanual pelvic examinations performed in emergency departments. West J Med. 2001;175:240.

5. Padilla, LA, Radosevich, DM, Milad, MP. Limitations of the pelvic examination for evaluation of the female pelvic organs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:84.

6. Reardon, RF, Joing, SA. First trimester pregnancy. In Ma OJ, Mateer J, Blaivas M, eds.: Emergency Ultrasound, 2nd ed, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.