Chapter 47 Acute Pancreatitis and Peripancreatic Fluid Collections

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Transgastric Drainage of Acute Pancreatic Fluid Collection

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Transgastric Drainage of Acute Pancreatic Fluid Collection

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis may be clinically mild or severe. Clinically severe acute pancreatitis is usually a result of pancreatic glandular necrosis. The morbidity and mortality of acute pancreatitis are significantly higher when pancreatic necrosis is present, especially when infection of the necrosis occurs.1 Patients with pancreatic necrosis must be identified so that appropriate management can be undertaken. The management of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis has shifted from early surgical débridement (necrosectomy) to aggressive intensive medical care. Specific criteria for operative or nonoperative intervention have been developed.2,3 Advances in radiologic imaging and aggressive medical management with emphasis on prevention of infection have allowed for prompt identification of complications and improvement in outcome for these patients.4 Several types of pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections may arise as a result of acute pancreatitis,5 including acute fluid collections, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic abscesses, and organized pancreatic necrosis. This chapter reviews more recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis and peripancreatic fluid collections.

Presentation and Classification of Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis usually has a rapid onset manifested by upper abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and elevated serum levels of pancreatic enzymes. Gallstone and alcohol-induced pancreatitis are the most common causes in the United States. Box 47.1 lists causes of pancreatitis. Several classifications of severity of illness for acute pancreatitis are used to identify patients at risk for developing complications (Table 47.1).6,7

| RANSON’s CRITERIA OF SEVERITY | |

|---|---|

| At Admission | During Initial 48 Hours |

| Age >55 yr | Hematocrit decrease >10% |

| WBC >16,000/mm3 | BUN increase >5 mg/dL |

| Blood glucose >200 mg/dL | Serum calcium <8 mg/dL |

| Serum LDH >350 IU/L | Pao2 <60 mm Hg |

| Serum AST >250 IU/L | Base deficit >4 mEq/L |

| Fluid sequestration >6 L | |

| Score ≥3 is considered severe | |

| APACHE II SCORE* | |

| Score ≥8 is considered severe | |

| GLASGOW CRITERIA | |

| Within 48 hr of hospitalization | |

| Age >55 yr | |

| WBC >15,000/mm3 | |

| Glucose >180 mg/dL | |

| BUN >45 mg/dL | |

| LDH >600 U/L | |

| Albumin <3.3 g/dL | |

| Calcium <8 mg/dL | |

| Pao2 <60 mm Hg | |

| Score ≥3 is considered severe | |

| BISAP SCORE | |

| BUN >25 mg/dL | |

| Impaired mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale score <15) | |

| SIRS—defined as ≥2 of the following | |

| Temperature of <36° C or >38° C | |

| Respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or Paco2 <32 mm Hg | |

| Pulse >90 beats/min | |

| WBC <4000/mm3 or >12,000/mm3 or >10% immature bands | |

| Age >60 yr | |

| Pleural effusion detected on imaging | |

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BISAP, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Paco2, arterial carbon dioxide tension; Pao, arterial oxygen tension; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; WBC, white blood cell count.

* Acute physiology score + age points + chronic health points.5

Ranson’s score consists of 11 clinical signs with prognostic significance; 5 signs are measured at the time of admission, and 6 signs are measured between admission and 48 hours later. There is good correlation between the number of Ranson signs and the incidence of systemic complications and the presence of pancreatic necrosis.6 The Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score is a grading system based on 12 physiologic variables, patient age, and prior history of severe organ system insufficiency or immunocompromised state.6 This score allows stratification of illness severity on admission and may be recalculated daily. Severe acute pancreatitis is present if there are three or more Ranson’s criteria, if the APACHE II score is 8 or greater, or if clinical findings of one or more of the following are present: shock, renal insufficiency, or pulmonary insufficiency.6 The Glasgow scoring system is another classification system.7 In contrast to Ranson’s criteria, the variables apply if they occur at any time within 48 hours. More recently, a bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) score was developed.8 The BISAP score has five variables: blood urea nitrogen greater than 25 mg/dL, impaired mental status, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, age older than 60 years, and pleural effusion detected on imaging. One point is assigned for each variable within 24 hours of presentation to yield a composite score of 0 to 5 (see Table 47.1).

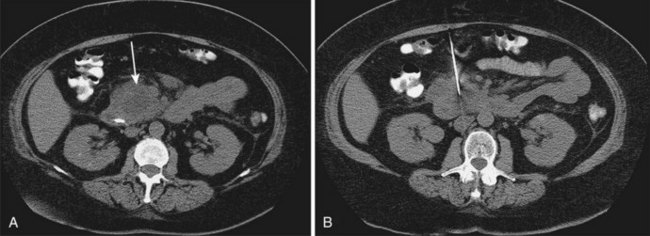

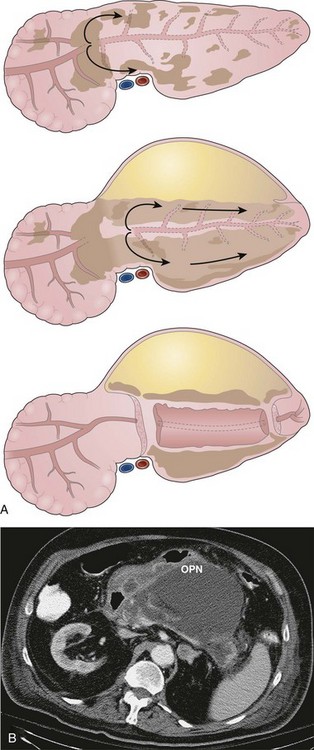

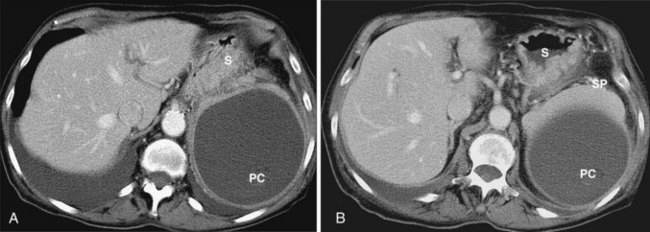

Acute pancreatitis may be classified histologically as interstitial-edematous or necrotizing based on the inflammatory changes of the pancreatic parenchyma.9 According to the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis in 1992, pancreatic necrosis is defined as one or more diffuse or focal areas of nonviable pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 47.1).9 Pancreatic glandular necrosis is usually associated with peripancreatic fat necrosis.9–11 By definition, the presence of pancreatic necrosis represents a severe form of acute pancreatitis.9 Approximately 20% to 30% of the 185,000 new cases of acute pancreatitis per year in the United States are necrotizing.12,13

Management of Mild Acute Pancreatitis (Interstitial-Edematous)

The management of patients with clinically mild or interstitial pancreatitis is almost entirely supportive. Patients with this form of pancreatitis generally have a self-limited course. There is no role for antibiotic therapy or nutritional support. The goal of management is to identify the etiology of the pancreatitis and to treat it appropriately. Identification of gallstones in the absence of other factors should be managed with cholecystectomy. Potentially offending drugs should be discontinued, and hyperlipidemia should be addressed. If there is alcohol abuse, a rehabilitation program should be offered to the patient. In some patients, an etiology for acute pancreatitis is not identified, and recurrent attacks occur. The management of these patients is controversial, specifically as it relates to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and pancreas divisum. Data support pursuing endoscopic evaluation of these entities,14 although there are no randomized trials proving effectiveness of endoscopic therapy.15

Identification and Clinical Importance of Pancreatic Necrosis

Pancreatic necrosis may be pathologically identified at surgery or autopsy. The radiographic diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis is determined by dynamic intravenous contrast–enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT).10 Because the normal pancreatic microcirculation is disrupted during acute necrotizing pancreatitis, contrast-enhanced abdominal CT shows a lack of normal contrast enhancement of affected portions of the pancreas (see Fig. 47.1)16; this may be better detected several days after initial clinical presentation. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT is the “gold standard” for noninvasive diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis, with an accuracy of greater than 90% when more than 30% glandular necrosis is present.10 The presence of radiographically detected pancreatic necrosis markedly increases the morbidity and mortality associated with acute pancreatitis.17 As the percentage of glandular necrosis increases, the morbidity increases.

Theoretically, contrast medium may cause significant additional reductions of capillary flow, which has been shown to aggravate acute pancreatitis in experimental studies. However, a more recent study in men with severe acute pancreatitis compared patients who did not receive contrast medium with patients who did. Patients in whom contrast medium was administered did not show deterioration of acute pancreatitis.18 The overall mortality in severe acute pancreatitis is approximately 30%.13 The mortality occurs in two phases. Early deaths (1 to 2 weeks after onset of pancreatitis) are due to multisystem organ failure from release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines.1 Late deaths result from local or systemic infections.19 As long as acute necrotizing pancreatitis remains sterile, the overall mortality is approximately 10%. The mortality rate at least triples if infected necrosis occurs.12

Patients with sterile necrosis and high severity of illness scores (Ranson’s scores, APACHE II scores) accompanied by multisystem organ failure, shock, or renal insufficiency have a significantly higher mortality.20 Myriad systemic and local complications of acute necrotizing pancreatitis may occur. Systemic complications have been detailed elsewhere2 and include adult respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal failure, shock, coagulopathy, hyperglycemia, and hypocalcemia. Local complications include gastrointestinal bleeding, infected necrosis, and adjacent bowel necrosis. Late local complications that may require therapy include development of pancreatic abscess or pancreatic pseudocyst. Early therapy of acute necrotizing pancreatitis consists of the combination of aggressive supportive intensive medical care and prevention of infection using prophylactic antibiotics. Late management requires recognition of local infectious complications (pancreatic infection) and the initiation of aggressive débridement strategies. Infected necrosis develops in 30% to 70% of patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis and accounts for more than 80% of deaths from acute pancreatitis.1,3 The risk of infected necrosis increases with increasing amounts of pancreatic glandular necrosis and length of time from onset of acute pancreatitis, peaking at 3 weeks.1,3

Infection in Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Because the development of infected necrosis significantly increases the mortality of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, prevention of infection is critical. In experimental acute necrotizing pancreatitis, pancreatic infection occurs primarily as a result of bacterial translocation from the colon.21 Several animal studies have shown a decrease in pancreatic infection and mortality using orally administered antibiotics for “selective decontamination” of the gut or intravenous antibiotics with high pancreatic tissue penetration.21–23 Similarly, human studies have shown benefits from orally administered antibiotics with or without rectally administered antibiotics for “selective decontamination” of the gut.24,25 This regimen has not gained acceptance.

The use of systemic antibiotics for the prevention of pancreatic infection has been studied extensively. Numerous studies have been published in animals and humans regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In addition, several meta-analyses have been performed showing conflicting results. The evidence does not show convincingly that the use of prophylactic antibiotics decreases mortality and need for surgery, although these do seem to decrease in nonpancreatic infections.26–30 At the present time, if administration of prophylactic antibiotics is chosen, intravenous antibiotics with excellent pancreatic tissue penetration (extended penicillins, carbapenems, or fluoroquinolones) is recommended. Duration of therapy of 2 weeks is advocated by some experts.

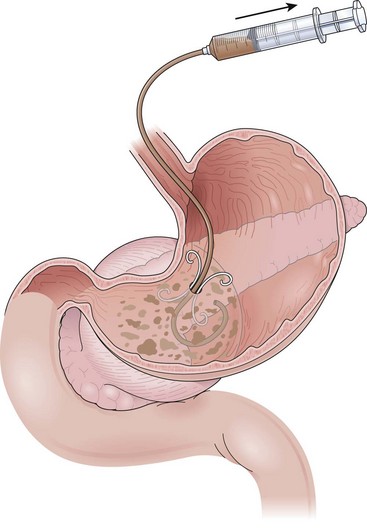

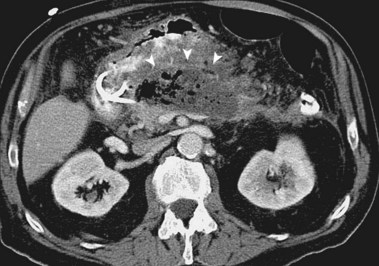

Sterile and infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis can be difficult to distinguish clinically because both may produce fever, leukocytosis, and severe abdominal pain. The distinction is important because the mortality in patients with infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis without intervention is nearly 100%.12 The bacteriologic status of the pancreas may be determined by CT-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue or fluid (Fig. 47.2).31,32 This aspiration method is safe and accurate with a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 99%, and it is recommended in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis who experience clinical deterioration or who do not experience clinical improvement despite aggressive supportive care.2 Ultrasound-guided aspiration may have a lower sensitivity and specificity33 but can be performed at the bedside. Surveillance aspiration may be repeated on a weekly basis as clinically indicated.

Role of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Severe Acute Gallstone Pancreatitis

Gallstone pancreatitis is caused by impaction of a stone within the common channel of the ampulla of Vater. In most cases, the stone passes without therapy. It is assumed that endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and biliary sphincterotomy would improve the outcome of gallstone pancreatitis because removal of an impacted stone would relieve obstruction to the flow of pancreatic secretions. Initial studies performing urgent (within 72 hours of admission) ERCP and biliary sphincterotomy (if a stone is identified) in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis and choledocholithiasis showed an improved outcome in only the group of patients presenting with clinically severe acute pancreatitis.34 The improvement was attributed to relief of pancreatic ductal obstruction produced by an impacted gallstone in the common biliary-pancreatic channel of the ampulla of Vater. More recent studies suggest the improved outcome after ERCP and sphincterotomy in gallstone pancreatitis results from reduced biliary sepsis, rather than a true improvement in pancreatitis.35,36

In the presence of pancreatic ductal disruption, a frequent occurrence in acute necrotizing pancreatitis,37 introduction of infection by incidental pancreatography during ERCP may theoretically occur, transforming acute necrotizing pancreatitis from sterile to infected. ERCP in patients with severe gallstone acute pancreatitis must be employed judiciously and reserved for patients with suspected biliary obstruction based on hyperbilirubinemia and clinical cholangitis because it is unlikely that the ampulla is obstructed in the presence of a normal serum bilirubin.38,39 Other imaging modalities, such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, may be used in patients with severe biliary pancreatitis with the goal of selectively performing ERCP in patients with documented bile duct stones.7,40 Whether empiric biliary sphincterotomy should be performed if bile duct stones are not identified is unknown, but this seems to be a reasonable approach.41

Nutritional Support for Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

To meet increased metabolic demands and to “rest” the pancreas, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) administered through a central venous catheter was used for nutritional support in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. TPN does not hasten resolution of acute pancreatitis or preserve gut integrity, an important factor in preventing bacterial translocation. Randomized prospective studies of TPN and enteral feeding (through a nasoenteric feeding tube placed radiographically beyond the ligament of Treitz) instituted within 48 hours of onset of severe acute pancreatitis42,43 showed that enteral feeding was well tolerated without adverse clinical effects and resulted in significantly fewer total and infectious complications. In a meta-analysis, enteral nutrition significantly reduced mortality, infectious complications, and pancreatic infections in patients with predicted severe pancreatitis compared with TPN.44 The cost of nutritional support was threefold higher in the TPN group.42 Acute phase response and disease severity scores were significantly improved after enteral nutrition.43

This form of enteral feeding seems to be preferable in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis in the absence of a significant ileus.45 This approach has been extended to nasogastric feeding. In a review of four studies comprising 92 patients in which nasogastric feeding was compared with nasojejunal feeding, mortality and intolerance to feeding were similar.46

Enteral feeding is the preferred strategy with TPN reserved for patients when the gut has failed or administration of enteral nutrition is impossible for other reasons (e.g., prolonged ileus, complex pancreatic fistulas, abdominal compartment syndrome).47 Various endoscopic techniques are available for placing nasojejunal feeding tubes in the setting of acute pancreatitis.47 One method avoids the need to transfer the guidewire from the mouth to the nose. A small-caliber endoscope is passed transnasally into the duodenum.48 A guidewire is advanced through the endoscope beyond the ligament of Treitz. The endoscope is withdrawn leaving the guidewire in place. The tube is passed over the guidewire with or without fluoroscopic guidance.

Interventions for Pancreatic Necrosis

The timing and type of pancreatic intervention for patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis are controversial. Because the mortality from sterile acute necrotizing pancreatitis is approximately 10%, and surgical intervention has not been shown to reduce this figure, most investigators recommend supportive medical therapy in this group.12 Conversely, infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis is traditionally considered uniformly fatal without intervention,12 although small, retrospective studies found that antibiotic therapy alone was effective in a select group of patients.49,50 Surgical pancreatic débridement (necrosectomy) remains the standard with which other drainage strategies are compared and may require multiple abdominal reexplorations.45

Necrosectomy should be undertaken soon after confirmation of infected necrosis. The role of surgery in patients with multisystem organ failure and sterile necrosis remains unproved, although this scenario is frequently cited as an indication for surgical débridement.51 Additionally, the longer that surgical intervention can be delayed from the onset of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, the better the patient survival52; this is probably related to improved demarcation between viable and necrotic tissue at the time of operation. The role of delayed necrosectomy (after resolution of multisystem organ failure) in sterile acute necrotizing pancreatitis likewise is controversial. Some investigators advocate débridement in patients who remain systemically ill 4 to 6 weeks after onset of acute pancreatitis with fever, weight loss, intractable abdominal pain, inability to eat, and “failure to thrive.”2,53,54 Others believe that delayed necrosectomy is unnecessary as long as the process remains sterile.54

Surgical Débridement for Pancreatic Necrosis

Surgical methods for treatment of necrosis vary. There are three main types of surgical débridement: conventional drainage, open or semiopen procedures, or closed procedures.45 Conventional drainage involves necrosectomy with placement of standard surgical drains and reoperation on demand (fever, leukocytosis, lack of improvement by imaging studies). Open or semiopen management employs necrosectomy and either scheduled repeat laparotomies or open packing that leaves the abdominal wound exposed for frequent dressing changes. Closed management involves necrosectomy with extensive intraoperative lavage of the pancreatic bed. The abdomen is closed over large-bore drains for continuous high-volume postoperative lavage of the lesser sac.

Most surgeons have abandoned the conventional surgical approach of débridement because inadequately removed necrotic tissue becomes or remains infected and results in a mortality of approximately 40%.3 In all procedures except the closed technique, multiple operations are frequently required to remove the necrotic pancreatic and peripancreatic material.3 Leaving the abdomen open avoids the need for formal laparotomies; packing may be changed in the intensive care unit. Repeated débridement and manipulation of the abdominal viscera using the open and semiopen techniques result in a high rate of postoperative local complications such as pancreatic fistulas, small and large bowel complications, and bleeding from the pancreatic bed. Pancreatic and gastrointestinal tract fistulas occur in 41% of patients after surgical necrosectomy and often require additional surgery for closure.55,56 The mortality using open or closed techniques is approximately 20%.3

Percutaneous (Interventional Radiology) Therapy

Successful percutaneous therapy for infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis has been described using large-bore percutaneous catheters up to 28-Fr diameter in conjunction with aggressive irrigation.57 At a mean of 9 days after hospital admission for necrotizing pancreatitis with medically uncontrolled sepsis, 34 patients had percutaneous drainage and irrigation catheters inserted into the pancreatic collection. An average of three separate catheter sites per patient and four catheter exchanges per patient was necessary for removal of necrotic material. Pancreatic surgery was completely avoided in 16 patients (47%). Control of sepsis with delayed elective surgery for repair of external pancreatic fistulas related to catheter placement was achieved in nine patients. Nine patients required immediate surgery for failure of percutaneous therapy. The mortality was 12% in these ill patients, many of whom had multisystem organ failure. In a similar fashion, Echenique and associates58 described successful percutaneous drainage of necrosis in 20 patients with documented necrosis. Solid debris was removed percutaneously using basket extraction techniques. Similar results have been obtained by other authors, although percutaneous therapy is most often used to improve immediate sepsis and delay necrosectomy.59,60 Percutaneous access has also been used to allow subsequent passage of rigid endoscopes for débridement of necrosis.61

Flexible Endoscopic Therapy

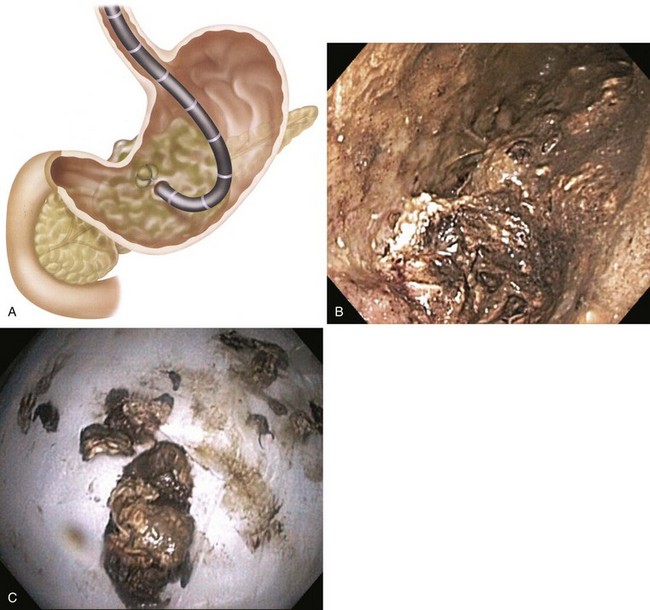

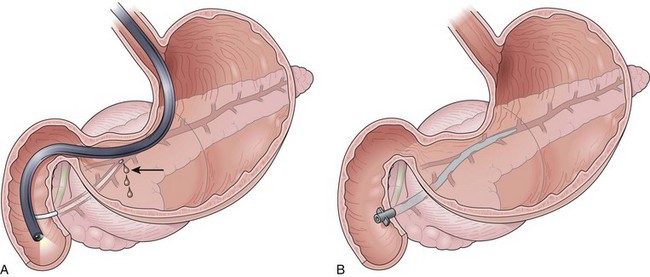

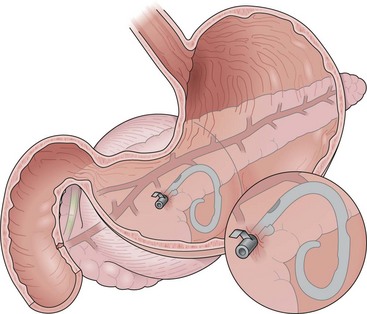

Successful endoscopic drainage of symptomatic sterile or infected pancreatic necrosis several weeks after the onset of severe necrotizing pancreatitis has been described.62 The initial descriptions used transmural placement (transgastric or transduodenal) of internal 10-Fr diameter drainage catheters plus a 7-Fr nasopancreatic irrigation tube into the retroperitoneum. The catheters are placed through a tract dilated up to 20 mm (Fig. 47.3). With this method, solid debris flows around the catheters through the transenteric tract. Complete nonsurgical resolution has been achieved in 84% of patients with this form of late, or “organized” pancreatic necrosis.63,64

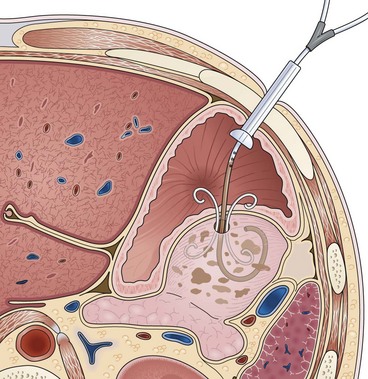

Complications of endoscopic therapy (described in more detail in the section on peripancreatic fluid collections) include perforation, bleeding, and infection. Adjuvant percutaneous drains using this technique are often required to drain peripheral collections away from the body of the pancreas. Beginning in 2005, the flexible endoscopic approach evolved to incorporate direct endoscopic débridement.65 Rather than relying on irrigation to débride necrotic material, the transmural entry site is dilated to a much larger diameter to allow passage of an upper endoscope directly inside the necrotic cavity to allow “direct” débridement (Fig. 47.4). Direct endoscopic necrosectomy has been shown to be superior to the initially described irrigation method with a higher success rate and less need for percutaneous catheters.66 There are now many series on this approach with success rates of approximately 80%.67–73

Multiple procedures are nearly uniformly required before complete resolution is achieved. The drainage options for patients with pancreatic necrosis are expanding. The experience using newer, nonsurgical drainage procedures is limited, and no interdisciplinary comparative data exist. When deciding on the timing or treatment modality to be employed in these complex patients, the expertise of the local surgeon, interventional endoscopist, and interventional radiologist must be considered. Nonsurgical drainage of pancreatic necrosis, whether performed acutely in the first weeks or subacutely at 1 month or more after pancreatitis onset, should be undertaken only by expert interventional endoscopists or interventional radiologists familiar with the potential complications and time required for successful pancreatic drainage. Improperly drained sterile necrosis may lead to life-threatening infected necrosis. An upfront team approach in planning pancreatic interventions is useful because some patients may benefit from multimodality drainage. The decision to intervene should be based on infection of the necrosis or, in the setting of sterile necrosis, severe clinical symptoms such as gastric outlet obstruction, intractable abdominal pain, or failure to thrive.74

Long-Term Sequelae of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

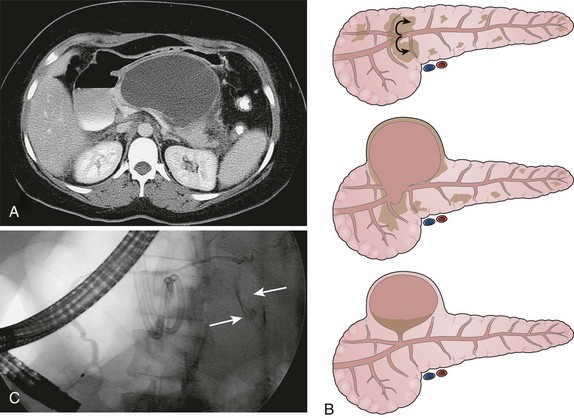

Despite the enormous cost of caring for patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis, mean quality-of-life outcomes up to 2 years after treatment of pancreatic necrosis are similar to outcomes obtained with coronary artery bypass grafting.75 The long-term clinical endocrine and exocrine consequences of acute necrotizing pancreatitis seem to depend on several factors including the severity of necrosis, etiology (alcoholic vs. nonalcoholic), continued use of alcohol, and the degree of surgical pancreatic débridement.76 Exocrine function studies show persistent functional insufficiency in most patients up to 2 years after severe acute pancreatitis.77 Use of pancreatic enzymes should be restricted to patients with symptoms of steatorrhea and weight loss secondary to fat malabsorption. Although subtle glucose intolerance is frequent, overt diabetes mellitus is uncommon.78 Follow-up pancreatography frequently reveals obstructive pancreatic ductal abnormalities that may account for persistent symptoms of abdominal pain or acute recurrent pancreatitis (Fig. 47.5).79

Summary of Management of Clinically Severe Acute Pancreatitis

Box 47.2 summarizes the overall approach to the management of acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatic and Peripancreatic Fluid Collections

Pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) arise as complication of acute and chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma (including postsurgical). PFCs that occur as a result of acute pancreatitis include acute fluid collections, pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic abscesses, and organized pancreatic necrosis (Table 47.2). These collections are amendable to endoscopic drainage. This section outlines the nomenclature, endoscopic drainage methods, and outcomes after endoscopic intervention of PFCs. Although there are other drainage options for these collections (percutaneous and surgical), these are not discussed in detail. Many gastroenterologists assume that any PFC arising as a consequence of acute pancreatitis represents a pancreatic pseudocyst. This assumption is incorrect, and it is important to recognize that several distinct entities fall under the general terms of peripancreatic and pancreatic fluid collections. In 1985, Kozarek and colleagues80 reported transmural (transgastric and transduodenal) placement of an endoprosthesis into pancreatic pseudocysts in four patients. Subsequently, a large body of literature describing endoscopic drainage of PFCs has emerged.

Table 47.2 Types of Pancreatic Fluid Collections Complicating Acute Pancreatitis

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute fluid collection | Collection of enzyme-rich pancreatic juice occurring early (within 48 hr) in the course of acute pancreatitis, located in or near the pancreas, and always lacks well-defined wall of granulation tissue or fibrous tissue |

| Acute pseudocyst | Collection of pancreatic juice enclosed by wall of nonepithelialized granulation tissue, arises as a consequence of acute pancreatitis, requires at least 4 wk to form, and is devoid of significant solid debris |

| Pancreatic necrosis (early) | Diffuse or focal area of nonviable pancreatic parenchyma >30% of the gland by contrast-enhanced CT, which is typically associated with peripancreatic fat necrosis |

| Organized or walled-off pancreatic necrosis (late) | Evolution of acute necrosis to partially encapsulated, well-defined collection of pancreatic juice and necrotic debris |

| Pancreatic abscess | Circumscribed intraabdominal collection of pus, usually in proximity to pancreas, containing little or no pancreatic necrosis, which arises as a consequence of acute pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma |

CT, computed tomography.

Types of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Acute Fluid Collections

Acute fluid collections arise early in the course of acute pancreatitis, are usually peripancreatic in location, and usually resolve without sequelae but may evolve into pancreatic pseudocysts (Fig. 47.6). Acute fluid collections rarely require drainage.5,81

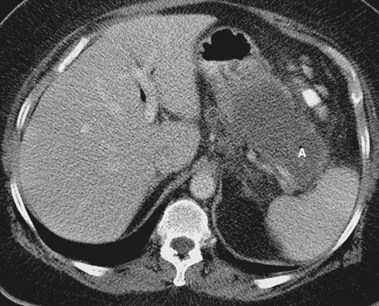

Acute Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Acute pancreatic pseudocysts arise as a sequela of acute pancreatitis, require at least 4 weeks to form, and are devoid of significant solid debris (Fig. 47.7A). An acute pancreatic pseudocyst usually forms as a result of limited pancreatic necrosis that produces a pancreatic ductal leak (Fig. 47.7B and C). Alternatively, areas of pancreatic and peripancreatic fat necrosis may completely liquefy over time and become a pseudocyst.82 Despite the requirement of at least 4 weeks for a pseudocyst to form, this time period in and of itself does not define the collection as a pancreatic pseudocyst. In patients with significant pancreatic necrosis (≥30%), the early acute pancreatic necrosis and peripancreatic necrosis may evolve into a collection that resembles a pseudocyst radiographically but has been present for 4 or more weeks (see the next section on organized or walled-off pancreatic necrosis). By definition, if these collections contain significant solid debris, they are not pseudocysts, and endoscopic treatment of these collections by typical pseudocyst drainage methods may result in infectious complications because of inadequate removal of solid debris.62,83

Organized or Walled-off Pancreatic Necrosis

Pancreatic necrosis is defined as nonviable pancreatic parenchyma usually with associated peripancreatic fat necrosis.9 In the earliest form, this entity is detected radiographically on contrast-enhanced CT by the presence of nonenhancing pancreatic parenchyma (see Fig. 47.1). Pancreatic necrosis is frequently accompanied by the development of major pancreatic ductal disruptions.84 The collection may continue to evolve over several weeks and expand the initial area of necrosis and contain both liquid and solid debris (Fig. 47.8). The resulting collection has been referred to as organized or walled-off pancreatic necrosis to differentiate this process from the early (acute) phase of pancreatic necrosis.62,63,85

As mentioned previously, the radiographic appearance of organized pancreatic necrosis on CT may be similar to an acute pseudocyst. Because the underlying solid debris is frequently not discernible by CT,86 its homogeneous appearance may lead one to embark on standard pseudocyst drainage methods, which do not remove the underlying solid material adequately. Serious infectious complications may result.62,83,87 A more recent study showed that there are features on CT that can distinguish walled-off pancreatitis necrosis from pancreatic pseudocysts.88 The findings seen with walled-off pancreatitis necrosis include larger size, extension to the paracolic space, irregular wall definition, presence of fat attenuation debris within the collection, and pancreatic deformity or discontinuity. Other CT correlates that indicate the presence of walled-off pancreatitis necrosis include significant necrosis on an early contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained at the time of—or soon after—the initial bout of pancreatitis and evolution of changes on serial CT scans.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging before attempted drainage can also delineate the solid debris within the collection (Fig. 47.9).88 Finally, a repeat abdominal CT scan after endoscopic drainage depicts solid material after some of the liquid component has been evacuated (Fig. 47.10).87 Endoscopic findings at the time of drainage may alert the endoscopist to the presence of necrotic debris within the collection. If the collection is drained transmurally, solid material may be seen to flow from the collection; the presence of chocolate-brown or extremely turbid fluid (in the absence of clinical infection) also suggests underlying necrosis. During pancreatography, the finding of complete main pancreatic duct disruption suggests that pancreatic necrosis occurred during the initial course of pancreatitis and may be present in the collection. During contrast agent injection, either through the main pancreatic duct or transmurally, the finding of large filling defects within the collection denotes the presence of solid material.

If any or all of the aforementioned findings are recognized, appropriate steps must be taken to evacuate the underlying solid debris to prevent secondary infection (see section on endoscopic methods of drainage of PFCs later). Overall, one should consider the evolution of a pancreatic collection from the early phase of acute pancreatic necrosis toward a pseudocyst as a spectrum, with walled-off pancreatitis necrosis as an intermediate stage, but also realizing that some collections might not ever become completely liquefied.

Pancreatic Abscess

A pancreatic abscess is defined as a collection of pus in close proximity to the pancreas (Fig. 47.11). Some authors include infected pancreatic pseudocysts in the definitions of an abscess but not infected pancreatic necrosis. Pancreatic abscesses may arise from limited pancreatic or peripancreatic fat necrosis that subsequently liquefies and becomes infected.5

Chronic Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Chronic pseudocysts are a complication of chronic pancreatitis. Obstruction of the main pancreatic duct from strictures or stones results in upstream ductal blowout. Resultant symptoms requiring drainage are similar to the symptoms described for acute pseudocysts. In addition, symptomatic pancreatic ascites and pancreaticopleural fistulas can occur and are amendable to endoscopic therapy.89

Indications for Drainage of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Acute Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Pancreatic pseudocysts do not usually produce symptoms, unless they are large enough to compress surrounding structures such as the stomach, duodenum, or bile duct with resultant development of abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, early satiety, weight loss, or jaundice. Pseudocyst size alone is not an indication for drainage, although pseudocysts larger than 6 cm in maximal diameter tend to be symptomatic.90 Progressive enlargement of a pseudocyst in an asymptomatic patient is considered by some authors to be an indication for drainage.91 An infected pseudocyst is an absolute indication for drainage.

Pancreatic Necrosis

The indications for and the timing of drainage of sterile pancreatic necrosis are controversial. Pancreatic necrosis is not amendable to endoscopic drainage until the process becomes organized, which usually occurs several weeks after onset of pancreatitis. If the process remains sterile, the general indications for drainage are refractory abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, or failure to thrive (continued systemic illness, anorexia, and weight loss) 4 or more weeks after the onset of acute pancreatitis.62 The severity of CT scan findings alone is not an indication for drainage. Because endoscopic drainage of these collections is more technically difficult, carries a higher rate of complications, and tends to involve more severely ill patients, the decision to intervene endoscopically in patients with sterile pancreatic necrosis must be carefully considered.

Alternative management options to endoscopic drainage include nutritional support with parenteral or enteral jejunal feeding and nonendoscopic drainage methods such as percutaneous or surgical drainage.74 The final management option is usually based on local expertise and severity of comorbid medical illnesses. These patients ideally are best managed by a multidisciplinary approach.87 Infected pancreatic necrosis is considered an indication for drainage. Infected necrosis may be indistinguishable clinically from sterile necrosis because of leukocytosis and fever. Percutaneous fine needle aspiration may be required to determine the bacteriologic status of the necrosis.

Evaluation before Drainage

Endoscopic Methods of Drainage of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

The following methods apply to endoscopic drainage of PFCs that do not have significant underlying solid debris (necrosis), such as acute pancreatic pseudocysts. The endoscopic management of organized or walled-off pancreatic necrosis is addressed separately. Endoscopic approaches to pseudocysts are transpapillary drainage,97,98 transmural drainage,99 and combined transpapillary and transmural drainage.93,100 The decision to proceed with one approach over another is based on the anatomic relationship of the collection to the stomach or duodenum, the presence of ductal communication, and the size of the collection. If the stomach or duodenum is not in close apposition to the wall of the collection (within 1 cm by CT), it is not approachable transmurally. If the collection is very large, attempted transpapillary drainage alone in the presence of a ductal communication may result in infection because the transpapillary drainage process is relatively slow, and contrast agent injection introduces bacterial or fungal organisms or both into the collection. The endoscopic approach to patients with large pseudocysts (>6 cm) using combined transpapillary and transmural drainage is analogous to the treatment of large bilomas complicating laparoscopic cholecystectomy using percutaneous drainage for the biloma and endoscopic therapy to close the biliary ductal leak.

Transpapillary Approach

If the collection communicates with the main pancreatic duct, placement of a pancreatic endoprosthesis with or without pancreatic sphincterotomy is a useful approach, especially for collections measuring 5 to 6 cm or less that are not otherwise approachable transmurally.101 The proximal end of the stent (toward the pancreatic tail) may enter the collection directly or bridge the area of leak into the pancreatic duct upstream from the leak (Fig. 47.12). Data suggest that complete bridging of the leak is the best approach.102 The diameter of pancreatic stent used depends on the pancreatic ductal diameter but is usually 7-Fr. The advantage of the transpapillary approach over the transmural approach is the avoidance of bleeding or perforation that may occur with transmural drainage. The disadvantage of transpapillary drainage is that pancreatic stents may induce scarring of the main pancreatic duct in patients whose pancreatic duct is otherwise normal (i.e., patients with acute pseudocysts and small side-branch disruption).103,104

Transmural Approach

Transmural drainage of PFCs is achieved by placing one or more large-bore stents through the gastric or duodenal wall (Fig. 47.13). There is no standardized approach to this method of drainage, and some authorities believe that EUS evaluation is mandatory before performing endoscopic transmural drainage of PFCs.107 EUS-guided and non–EUS-guided drainage is discussed.

Endoscopic Ultrasound–Guided Transmural Drainage

EUS may increase the success rate and reduce complications related to transmural entry of PFCs.108 There are two ways EUS can be used for transmural drainage of PFCs.109 The first is to use the echoendoscope to localize the collection in relationship to surrounding structures and endoscopic landmarks; the echoendoscope is removed, and a therapeutic endoscope is used to perform transmural drainage by puncturing into the collection as described subsequently under non–EUS-guided drainage. The second is to perform the evaluation and entry into the collection using direct EUS guidance. Transmural drainage of PFCs can be performed entirely under EUS guidance using Doppler-equipped therapeutic channel echoendoscopes.110 The lack of EUS availability does not preclude potential transmural drainage except in the following instances: small “window” of entry based on CT, especially in the absence of an endoscopically defined area of extrinsic compression or unusual location (Fig. 47.14); marginal, uncorrectable coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia; documented intervening varices; and failed transmural entry using non–EUS-guided techniques.111

Transmural Drainage without Endoscopic Ultrasound Guidance

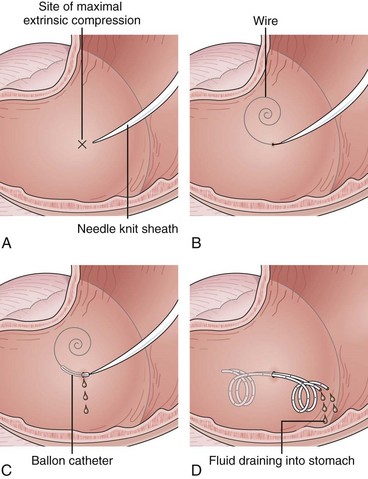

Needle-knife electrocautery is used to enter the collection at the point of maximal endoscopically visible extrinsic compression with or without prelocalization using a needle.112 Once entry into the collection has been achieved and a guidewire has been secured, the transmural tract is enlarged with a dilating balloon. The practice of enlarging the transmural tract with a sphincterotome has been abandoned because of the risk of bleeding.113 Another method is localization and entry into the collection using a large-caliber needle without electrocautery employing the Seldinger technique (see Video).101 This method seems to be safer because if the collection is not successfully entered with the needle (confirmed by aspiration of fluid or injection of radiopaque contrast agent), the needle is simply withdrawn without adverse sequelae. Similarly, if bleeding occurs on needle entry, if gross blood is aspirated, or if a visible hematoma develops, the needle is withdrawn to allow the vessel to tamponade. Another transmural entry site may be chosen during the same endoscopic session. Once the collection has been entered as confirmed by aspiration of fluid or injection of contrast agent, a guidewire is passed through the needle-knife or aspiration needle and coiled within the collection (Fig. 47.15). The transmural tract is dilated to 8 mm using standard biliary dilating balloons to allow placement of one or more double pigtail 10-Fr stents (see Fig. 47.15).

Follow-up

A short course of oral antibiotics is administered after uncomplicated attempted endoscopic drainage of noninfected pancreatic pseudocysts. Most outpatients do not require hospitalization.114 In the absence of suspected complications or worsening clinical course, a follow-up CT scan is obtained 4 to 6 weeks after the drainage procedure. The internal stents are endoscopically removed after documented radiographic resolution.

Endoscopic Drainage of Organized or Walled-off Pancreatic Necrosis

Because of the need to evacuate solid material, the endoscopic approach to drainage of organized or walled-off pancreatic necrosis differs from drainage of other PFCs. Generally, the transpapillary approach is inadequate to allow removal of solid debris. Transmural drainage is the preferred approach for these collections. After transmural entry into the collection as described previously, the gastric or duodenal wall is dilated to at least 15 mm on the initial endoscopy. Dilation allows a forward-viewing endoscope to be passed transmurally into the stomach for direct endoscopic necrosectomy as described earlier in the treatment of pancreatic necrosis (see Fig. 47.4). Two 10-Fr stents are placed to allow reaccess to the necrotic cavity for subsequent débridement. Although used much less often now, a 7-Fr irrigation tube can be placed into the collection (standard nasobiliary tube) for aggressive irrigation (see Fig. 47.3) allowing further débridement.

An alternative to nasocystic lavage is the placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube with placement of a “jejunal” extension tube into the collection (Fig. 47.16).115 The gastric port may be used for supplementing nutritional needs. Patients undergoing attempted endoscopic drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis should receive antibiotics before the procedure. It is recommended that outpatients be admitted to the hospital after the procedure for observation. Oral antibiotics are administered, and follow-up endoscopic débridement is performed until the collection has resolved as documented by follow-up CT. CT scans are obtained after the necrotic cavity appears to be completely débrided. The internal drains are endoscopically removed several weeks after complete resolution of the collection.

Complications of Endoscopic Therapy of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Life-threatening complications that may arise after attempted endoscopic drainage of PFCs are listed in Box 47.3. It is recommended that endoscopic drainage of PFCs not be performed without the availability of surgical and interventional radiology support. The most feared complications of transmural drainage are bleeding and perforation. Bleeding after transmural drainage may be managed supportively, endoscopically, surgically, or with angiographic embolization.114 If perforation occurs during attempted transgastric drainage and is limited to the gastric wall (does not involve the collection), it may be successfully managed nonsurgically, provided that a stent has not been placed through the perforation; the gastric wall rapidly closes with conservative treatment consisting of nasogastric suction and antibiotics. Some authors believe that transduodenal perforation may be managed conservatively because the perforation is retroduodenal,116 although this is not proven.

Results of Endoscopic Therapy of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Pancreatic Pseudocysts

The success rates, recurrence rates, and complication rates after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts are variable. Most authors have not used standardized criteria for defining pseudocysts, have used variable indications to perform drainage, have tended to lump acute and chronic pseudocysts into a single group, or have combined the results of transpapillary and transmural drainage. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts can be achieved in approximately 90% of cases with complication rates ranging from 5% to 10% and recurrence rates ranging from 6% to 18%.117,118 Retrospective data suggest similar success and complication rates between endoscopy and surgery for management of pseudocysts.119–121

Pancreatic Abscesses

Pancreatic abscesses defined as infected pseudocysts or peripancreatic liquefied necrosis have been successfully drained endoscopically.65,122–124

Organized or Walled-off Pancreatic Necrosis

The endoscopic approach to walled-off pancreatic necrosis has evolved since the initial descriptions.62,114 Subsequent modifications including dilating the transmural entry tract to 15 mm or greater at the initial procedure with a primary irrigation approach and direct endoscopic necrosectomy have resulted in better outcomes. Successful nonsurgical resolution is achieved in approximately 80% to 85% of patients.66–6870

Outcome Differences after Endoscopic Drainage of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

There are differences in success rates, complication rates, recurrences, and hospital stay for drainage of acute pseudocysts, chronic pseudocysts, and walled-off necrosis.114 These differences are due to differences in pathology, pathophysiology, and severity of illness between the groups. Patients with pancreatic necrosis tend to be more severely ill, and endoscopic evacuation of solid debris is less efficient than evacuation of liquid. In terms of recurrence rates, acute pancreatic ductal disruptions occurring in patients with necrosis frequently lead to a disconnected duct syndrome whereby the head and tail of the pancreas are not in communication.62,87 This situation leads to recurrent collections from the undrained viable pancreatic tail. Patients with acute pseudocysts tend to have less severe ductal abnormalities and lower recurrence rates. In addition to the type of pancreatic collection, the experience of the endoscopist seems to play a role in the success rate of drainage.125 Future prospective studies assessing skill acquisition are required to define the minimum number of collection drainage procedures at which competence can be achieved.

Conclusion

Pancreatic necrosis is being increasingly recognized because of physician awareness and improved radiologic imaging. The identification of pancreatic necrosis is important because the morbidity and mortality from acute pancreatitis are markedly increased when necrosis is present. Aggressive medical care with use of antibiotics and limitation of surgery or other types of pancreatic débridement to patients with infected necrosis are the mainstays of management (see Table 47.1). PFCs are heterogeneous, with different underlying pathologies and pathophysiologies. Each type of PFC is amendable to drainage, although not in every patient. Collections with only a fluid component that are distinguished by either apposition to the gastric or duodenal wall by CT or communication with the main pancreatic duct by pancreatography can be drained endoscopically using transmural or transpapillary approaches. Collections containing significant amounts of solid debris that are treated endoscopically require débridement techniques to evacuate solid debris. Endoscopists considering endoscopic therapy of a pancreatic collection must identify the type of collection being drained and exclude masqueraders of PFCs, such as cystic neoplasms. EUS-guided drainage may decrease the complications of bleeding and perforation during transmural entry of PFCs. Refinement in endoscopic techniques to improve the safety and efficacy of endoscopic therapy and comparative studies with other drainage methods are needed.

1 Beger HG, Rau B, Mayer J, Pralle U. Natural course of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1997;21:130-135.

2 Tenner S, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis: Nonsurgical management. World J Surg. 1997;21:143-148.

3 Rau B, Uhl W, Buchler MW, et al. Surgical treatment of infected necrosis. World J Surg. 1997;21:155-161.

4 Foitzik T, Klar E, Buhr HJ, et al. Improved survival in acute necrotizing pancreatitis despite limiting the indications for surgical debridement. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:187-192.

5 Baron TH, Morgan DE. The diagnosis and management of fluid collections associated with pancreatitis. Am J Med. 1997;102:555-563.

6 Banks PA, Freeman ML, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400.

7 Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, et alBritish Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004-1021.

8 Singh VK, Wu BU, Bollen TL, et al. A prospective evaluation of the bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis score in assessing mortality and intermediate markers of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:966-971.

9 Bradley ELIII. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586-590.

10 Balthazar EJ, Freeny PC, vanSonnenberg E. Imaging and intervention in acute pancreatitis. Radiology. 1994;193:297-306.

11 Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis: Medical and surgical management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:S78-S85.

12 Banks PA. Infected necrosis: Morbidity and therapeutic consequences. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:116-119.

13 Imrie CW. Underdiagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Adv Acute Pancreatitis. 1997;1:3-5.

14 Coyle WJ, Pineau BC, Tarnasky PR, et al. Evaluation of unexplained acute and acute recurrent pancreatitis using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, sphincter of Oddi manometry and endoscopic ultrasound. Endoscopy. 2002;34:617-623.

15 Clain JE, Pearson RK. Evidence-based approach to idiopathic pancreatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4:128-134.

16 Nuutinen P, Kivisaari L, Schroder T. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography and microangiography of the pancreas in acute human hemorrhagic/necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1988;3:53-60.

17 Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, et al. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology. 1990;174:331-336.

18 Uhl W, Roggo A, Kirschstein T, et al. Influence of contrast-enhanced computed tomography on course and outcome in patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2002;24:191-197.

19 Gloor B, Muller CA, Worni M, et al. Late mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2001;88:975-979.

20 Karimgani I, Porter KA, Langevin RE, et al. Prognostic factors in sterile pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1636-1640.

21 Marotta F, Geng TC, Wu CC, et al. Bacterial translocation in the course of acute pancreatitis: Beneficial role of nonabsorbable antibiotics and lactitol enemas. Digestion. 1996;57:446-452.

22 Foitzik T, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Ferraro MJ, et al. Pathogenesis and prevention of early pancreatic infection in experimental acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1995;222:179-185.

23 Mithofer K, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Ferraro MJ, et al. Antibiotic treatment improves survival in experimental acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:232-240.

24 Luiten EJ, Hop WC, Lange JF, et al. Controlled clinical trial of selective decontamination for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1995;222:57-65.

25 Luiten EJ, Hop WC, Lange JF, et al. Differential prognosis of gram-negative versus gram-positive infected and sterile pancreatic necrosis: Results of a randomized trial in patients with severe acute pancreatitis treated with adjuvant selective decontamination. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:811-816.

26 Jafri NS, Mahid SS, Idstein SR, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not protective in severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg.. 2009;197:806-813.

27 Wittau M, Hohl K, Mayer J, et al. The weak evidence base for antibiotic prophylaxis in severe acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:2233-2237.

28 Bai Y, Gao J, Zou DW, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:104-110.

29 Villatoro E, Bassi C, Larvin M: Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD002941, 2006.

30 de Vries AC, Besselink MG, Buskens E, et al. Randomized controlled trials of antibiotic prophylaxis in severe acute pancreatitis: Relationship between methodological quality and outcome. Pancreatology. 2007;7:531-538.

31 Gerzof SG, Banks PA, Robbins AH, et al. Early diagnosis of pancreatic infection by computed tomography-guided aspiration. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1315-1320.

32 Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, et alDutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Prevention, detection, and management of infected necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:104-110.

33 Rau B, Pralle U, Mayer JM, et al. Role of ultrasonographically guided fine-needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:179-184.

34 Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, London NJ, et al. Controlled trial of urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment for acute pancreatitis due to gallstones. Lancet. 1988;2:979-983.

35 Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, et al. Early treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis by endoscopic papillotomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:228-232.

36 Folsch UR, Nitsche R, Ludtke R, et al. Early ERCP and papillotomy compared with conservative treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. The German Study Group on Acute Biliary Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:237-242.

37 Neoptolemos JP, London NJ, Carr-Locke DL. Assessment of main pancreatic duct integrity by endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:94-99.

38 Baillie J. Treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:286-287.

39 Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, et al. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg. 2008;247:250-257.

40 Mofidi R, Lee AC, Madhavan KK, et al. The selective use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in the imaging of the axial biliary tree in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2008;8:55-60.

41 Sanjay P, Yeeting S, Whigham C, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and interval cholecystectomy are reasonable alternatives to index cholecystectomy in severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (GSP). Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1832-1837.

42 Kalfarentzos F, Kehagias J, Mead N, et al. Enteral nutrition is superior to parenteral nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis: Results of a randomized prospective trial. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1665-1669.

43 Windsor AC, Kanwar S, Li AG, et al. Compared with parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition feeding attenuates the acute phase response and improves disease severity in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1998;42:431-435.

44 Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, et al. Enteral nutrition reduced the risk of mortality and infectious complications in patients with severe acute pancreatitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1111-1117.

45 Yousaf M, McCallion K, Diamond T. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg.. 2003;90:407-420.

46 Petrov MS, Correia MI, Windsor JA. Nasogastric tube feeding in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review of the literature to determine safety and tolerance. JOP. 2008;9:440-448.

47 Gianotti L, Meier R, Lobo DN, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition: Pancreas. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:428-435.

48 DiSario JA, Baskin WN, Brown RD, et al. Endoscopic approaches to enteral nutritional support. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:901-908.

49 Kulling D, Bauerfeind P, Fried M. Transnasal versus transoral endoscopy for the placement of nasoenteral feeding tubes in critically ill patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:506-510.

50 Adler DG, Chari ST, Dahl TJ, et al. Conservative management of infected necrosis complicating severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:98-103.

51 Ramesh H, Prakash K, Lekha V, et al. Are some cases of infected pancreatic necrosis treatable without intervention? Dig Surg. 2003;20:296-300.

52 Rau B, Pralle U, Uhl W, et al. Management of sterile necrosis in instances of severe acute pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:279-288.

53 Mier J, Leon EL, Castillo A, et al. Early versus late necrosectomy in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:71-75.

54 Rattner DW, Legermate DA, Lee MJ, et al. Early surgical debridement of symptomatic pancreatic necrosis is beneficial irrespective of infection. Am J Surg. 1992;163:105-110.

55 Bradley EL3rd. Surgical indications and techniques in necrotizing pancreatitis. In: Bradley EL3rd, editor. Acute pancreatitis: Diagnosis and therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1994:105-117.

56 Tsiotos GG, Smith CD, Sarr MG. Incidence and management of pancreatic and enteric fistulas after surgical management of severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1995;130:48-52.

57 Ho HS, Frey CF. Gastrointestinal and pancreatic complications associated with severe pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1995;130:817-823.

58 Echenique AM, Sleeman D, Yrizarry J, et al. Percutaneous catheter-directed debridement of infected pancreatic necrosis: Results in 20 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9:565-571.

59 Freeny PC, Hauptmann E, Althaus SJ, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided catheter drainage of infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Techniques and results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:969-975.

60 Bruennler T, Langgartner J, Lang S, et al. Percutaneous necrosectomy in patients with acute, necrotizing pancreatitis. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1604-1610.

61 Carter R. Percutaneous management of necrotizing pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2007;9:235-239.

62 Risse O, Auguste T, Delannoy P, et al. Percutaneous video-assisted necrosectomy for infected pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28(10 Pt 1):868-871.

63 Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, et al. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755-764.

64 Baron TH, Morgan DE. Organized pancreatic necrosis: Definition, diagnosis, and management. Gastroenterol Int. 1997;10:167-178.

65 Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Chahal P, et al. Peroral endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:943-951.

66 Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, et al. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: A new safe and effective treatment algorithm (videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92-100.

67 Gardner TB, Chahal P, Papachristou GI, et al. A comparison of direct endoscopic necrosectomy with transmural endoscopic drainage for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1085-1094.

68 Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, et al. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: A multicenter study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD study). Gut. 2009;58:1260-1266.

69 Charnley RM, Lochan R, Gray H, et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy as primary therapy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:925-928.

70 Escourrou J, Shehab H, Buscail L, et al. Peroral transgastric/transduodenal necrosectomy: Success in the treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1074-1080.

71 Hocke M, Will U, Gottschalk P, et al. Transgastral retroperitoneal endoscopy in septic patients with pancreatic necrosis or infected pancreatic pseudocysts. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:1363-1368.

72 Mathew A, Biswas A, Meitz KP. Endoscopic necrosectomy as primary treatment for infected peripancreatic fluid collections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:776-782.

73 Isayama H, Yamamoto K, Mizuno S, et al. NOTES and endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy for the GI endoscopist. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:270-273.

74 Voermans RP, Veldkamp MC, Rauws EA, et al. Endoscopic transmural debridement of symptomatic organized pancreatic necrosis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:909-916.

75 Baron TH, Morgan DE. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1412-1417.

76 Fenton-Lee D, Imrie CW. Pancreatic necrosis: Assessment of outcome related to quality of life and cost of management. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1579-1582.

77 Fernandez-Cruz L, Navarro S, Castells A, et al. Late outcome after acute pancreatitis: Functional impairment and gastrointestinal tract complications. World J Surg. 1997;21:169-172.

78 Nordback IH, Auvinen OA. Long-term results after pancreas resection for acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1985;72:687-689.

79 Bozkurt T, Maroske D, Adler G. Exocrine pancreatic function after recovery from necrotizing pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:55-58.

80 Kozarek RA, Brayko CM, Harlan J, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:322-328.

81 Angelini G, Cavallini G, Pederzoli P, et al. Long-term outcome of acute pancreatitis: A prospective study with 118 patients. Digestion. 1993;54:143-147.

82 Angelini G, Pederzoli P, Caliari S, et al. Long-term outcome of acute necrohemorrhagic pancreatitis: A 4-year follow-up. Digestion. 1984;30:131-137.

83 Adkisson KW, Baron TH, Morgan DE. Pancreatic fluid collections: Diagnosis and endoscopic management. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1998;9:61-72.

84 Kloppel G. Pathology of severe acute pancreatitis. In: Bradley EL3rd, editor. Acute pancreatitis: Diagnosis and therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1994:35-46.

85 Hariri M, Slivka A, Carr-Locke DL, et al. Pseudocyst drainage predisposes to infection when pancreatic necrosis is unrecognized. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1781-1784.

86 Uomo G, Molino D, Visconti M, et al. The incidence of main pancreatic duct disruption in severe biliary pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1998;176:49-52.

87 Baron TH, Morgan DE, Vickers SM, et al. Organized pancreatic necrosis: Endoscopic, radiologic, and pathologic features of a distinct clinical entity. Pancreas. 1999;19:105-108.

88 Morgan DE, Baron TH, Smith JK, et al. Pancreatic fluid collections prior to intervention: Evaluation with MR imaging compared with CT and US. Radiology. 1997;203:773-778.

89 Kozarek RA. Endotherapy for organized pancreatic necrosis: Perspectives on skunk-poking. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:820-822.

90 Takahashi N, Papachristou GI, Schmit GD, et al. CT findings of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN): Differentiation from pseudocyst and prediction of outcome after endoscopic therapy. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2522-2529.

91 Pai CG, Suvarna D, Bhat G. Endoscopic treatment as first-line therapy for pancreatic ascites and pleural effusion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1198-1202.

92 Yeo CJ, Bastidas JA, Lynch-Nyhan A, et al. The natural history of pancreatic pseudocysts documented by computed tomography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:411-417.

93 Libera ED, Siqueira ES, Morais M, et al. Pancreatic pseudocysts transpapillary and transmural drainage. HPB Surg. 2000;11:333-338.

94 Boggi U, Candio G, Campatelli A, et al. Nonoperative management of pancreatic pseudocysts: Problems in differential diagnosis. Int J Pancreatol. 1999;25:123-133.

95 Baron TH, Morgan DE, Vickers SM. Endoscopic transgastric drainage of a lymphocele. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:309-311.

96 Beckingham IJ, Krige JE, Bornman PC, et al. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1638-1645.

97 Itai Y, Moss AA, Goldberg HI. Pancreatic cysts caused by carcinoma of the pancreas: A pitfall in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1982;6:772-776.

98 Brugge WR. The role of EUS in the diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:S18-S22.

99 Barthet M, Sahel J, Bodiou-Bertei C, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:208-213.

100 Catalano MF, Geenen JE, Schmalz MJ, et al. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts with ductal communication by transpapillary pancreatic duct endoprosthesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:214-218.

101 Monkemuller KE, Baron TH, Morgan DE. Transmural drainage of pancreatic fluid collections without electrocautery using the Seldinger technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:195-200.

102 Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Walter A, et al. Transpapillary and transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:219-224.

103 Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, et al. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:245-252.

104 Telford JJ, Farrell JJ, Saltzman JR, et al. Pancreatic stent placement for duct disruption. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:18-24.

105 Kozarek RA. Pancreatic stents can induce ductal changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:93-95.

106 Smith MT, Sherman S, Ikenberry SO, et al. Alterations in pancreatic ductal morphology following polyethylene pancreatic stent therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:268-275.

107 Fockens P, Johnson TG, van Dullemen HM, et al. Endosonographic imaging of pancreatic pseudocysts before endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:412-416.

108 Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-1111.

109 Varadarajulu S. EUS followed by endoscopic pancreatic pseudocyst drainage or all-in-one procedure: A review of basic techniques (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(2 Suppl):S176-S181.

110 Seewald S, Ang TL, Kida M, et alEUS 2008 Working Group. EUS 2008 Working Group document: Evaluation of EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(2 Suppl):S13-S21.

111 Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Tamhane A, et al. Role of EUS in drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections not amenable for endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1107-1119.

112 Howell DA, Holbrook RF, Bosco JJ, et al. Endoscopic needle localization of pancreatic pseudocysts before transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:693-698.

113 Etzkorn KP, DeGuzman LJ, Holderman WH, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: Patient selection and evaluation of the outcome by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1995;27:329-333.

114 Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, et al. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:7-17.

115 Baron TH, Morgan DE. Endoscopic transgastric irrigation tube placement via PEG for debridement of organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:574-577.

116 Beckingham IJ, Krige JE, Bornman PC, et al. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1638-1645.

117 Baron TH. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:369-372.

118 Aljarabah M, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches for drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: A systematic review of published series. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1936-1944.

119 Melman L, Azar R, Beddow K, et al. Primary and overall success rates for clinical outcomes after laparoscopic, endoscopic, and open pancreatic cystgastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:267-271.

120 Johnson MD, Walsh RM, Henderson JM, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical management of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:586-590.

121 Varadarajulu S, Lopes TL, Wilcox CM, et al. EUS versus surgical cyst-gastrostomy for management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:649-655.

122 Vitale GC, Davis BR, Vitale M, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic drainage for pancreatic abscesses. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:140-146.

123 Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, et al. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:524-529.

124 Park JJ, Kim SS, Koo YS, et al. Definitive treatment of pancreatic abscess by endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:256-262.

125 Harewood GC, Wright CA, Baron TH. Impact on patient outcomes of experience in the performance of endoscopic pancreatic fluid collection drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:230-235.