26.1 Acute neonatal emergencies

Neonatal emergencies

The infant with breathing difficulty

The causes of respiratory distress are varied and are summarised in Table 26.1.1. They can be broadly divided into primary respiratory and non-respiratory causes. Primary respiratory pathology is a direct result of upper, lower or mixed airway pathology.

Respiratory distress attributed to lung parenchyma pathology

Clinical features

History

In addition to predisposing factors, a history of poor feeding often predates the collapse.

Other causes of respiratory distress presenting in the ED are:

Examination

The classic cardiac lesions presenting with respiratory distress in the neonatal period include:

Left to right shunting lesions (atrioventriculoseptal defects (AVSD) and ventriculoseptal defects (VSD)). Typically, large VSDs present between weeks 2 and 4 of life after the pulmonary pressures have reduced and this allows increased left to right flow with resultant pulmonary oedema. The infant will present with increasing tachypnoea, recession and poor feeding, in association with a loud cardiac murmur and crepitations audible in the chest.

Left to right shunting lesions (atrioventriculoseptal defects (AVSD) and ventriculoseptal defects (VSD)). Typically, large VSDs present between weeks 2 and 4 of life after the pulmonary pressures have reduced and this allows increased left to right flow with resultant pulmonary oedema. The infant will present with increasing tachypnoea, recession and poor feeding, in association with a loud cardiac murmur and crepitations audible in the chest. Duct-dependent obstructive left ventricle conditions (hypoplastic left heart, critical aortic stenosis and coarctation of the aorta). Once the ductus arteriosus closes around week 1 of life, the systemic circulation is no longer maintained. Infants present shocked, pale and with severe respiratory distress. Specifically they have weak femoral pulses and invariably a large liver.

Duct-dependent obstructive left ventricle conditions (hypoplastic left heart, critical aortic stenosis and coarctation of the aorta). Once the ductus arteriosus closes around week 1 of life, the systemic circulation is no longer maintained. Infants present shocked, pale and with severe respiratory distress. Specifically they have weak femoral pulses and invariably a large liver.The blue infant

The infant with possible seizures

Clinical features

Acute treatment

The collapsed infant

The most common entities to be considered include bacterial infection and viral syndromes. There are a number of other disorders that are uncommon, but demand diagnostic consideration because they are potentially life threatening, yet treatable (Table 26.1.2).

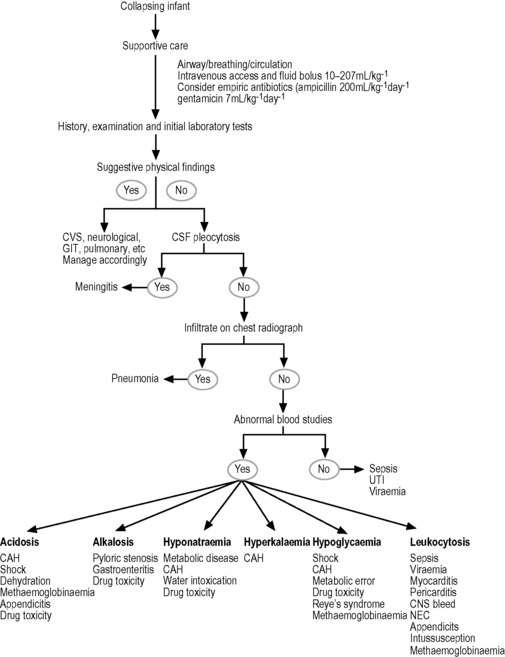

An infant who is critically ill in the first month of life should initially be presumed to have sepsis and empiric antibiotics commenced. As Escherichia coli, GBS, Listeria, and other anaerobes are the most likely causative organisms, a combination of ampicillin 200 mg kg–1 day–1 and gentamicin 7 mg kg–1 day–1 in divided doses is a reasonable starting point. In the case of suspected meningitis the addition of cefotaxime 200 mg kg–1 day–1 in divided doses may also be considered. This is a life-threatening situation; the airway, breathing, and circulation should be restored, vascular access obtained and supportive care commenced. The approach to the collapsed infant is presented in Figure 26.1.1.

Fig. 26.1.1 Approach to the collapsing infant.

Source: Adapted from Selbst SM 1985 The septic-appearing infant. Paediatr Emerg Care 3: 160–167.

Resuscitation of the newborn infant

Alexander R., Crabbe L., Sato Y., et al. Serial abuse in children who are shaken. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:58-60.

Brazelton T.B. Crying in infancy. Paediatrics. 1962;29:579-588.

Carey W.B. The effectiveness of parent counseling in managing colic. Paediatrics. 1994;94(3):333-334.

Forsyth B.W.C. Colic and the effect of changing formulas: A double blind, multiple-crossover study. J Paediatr. 1989;115:521-526.

Holzki J., Laschat M., Stratmann C. Stridor in the neonate and infant. Implications for the paediatric anaesthetist. Prospective description of 155 patients with congenital and acquired stridor in early infancy. Paediatr Anaestha. 1998;8(3):221-227.

ILCOR. International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Advisory statement: Resuscitation of the newly born infant. Paediatrics. 1999;103:56.

Illingworth R.S. Three month’s colic. Arch Dis Child. 1954;145:165-174.

Lucassen P.L.B.J., Assendelft W.J.J., Gubbels J.W., et al. Effectiveness of treatments for infantile colic: Systemic review. Bri Med J. 1998;316:1563-1569.

McKenzie S. Troublesome crying in infants: Effect of advice to reduce stimulation. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:1416-1420.

Millar K.R., Gloor J.E., Wellington N., Joubert G. Early neonatal presentations to the paediatric ED. Paediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16(3):145-150.

Poole S.R. The infant with acute, unexplained, excessive crying. Paediatrics. 1991;88(3):450-455.

Selbst S.M. The septic-appearing infant. Paediatr Emerg Care. 1985;3:160-167.

Singer J.I., Rosenberg N.M. A fatal case of colic. Paediatr Emerg Care. 1992;8(3):171-172.