14 Acute myocardial infarction

Salient features

History

• Family history of cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidaemia, gout

• Past history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), intermittent claudication and hyperlipidaemia

• History of oral contraceptives in young women

Examination

• Hands: nicotine staining of fingers

• Pulse: check pulse rate (keeping in mind heart block and tachycardia), rhythm (keeping in mind atrial fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmias)

• JVP may be raised in cardiac failure or right ventricular infarction

• Eyes: look for arcus senilis, xanthelasma

• Cardiac apex: look for double apical impulse (ventricular aneurysm)

• Auscultate for fourth heart sound, pericardial rub, pansystolic murmur of papillary muscle dysfunction (or ventricular septal defect)

Questions

What is Levine’s sign?

In acute myocardial infarction the patient often describes the pain by illustrating a clenched fist.

What is the clinical classification of myocardial infarction?

Type 1: spontaneous MI related to ischaemia caused by a primary coronary event such as plaque erosion and/or rupture, fissuring or dissection.

Type 2: MI secondary to ischaemia caused by either increased oxygen demand or decreased supply, such as coronary spasm, coronary embolism, anaemia, arrhythmias, hypertension or hypotension.

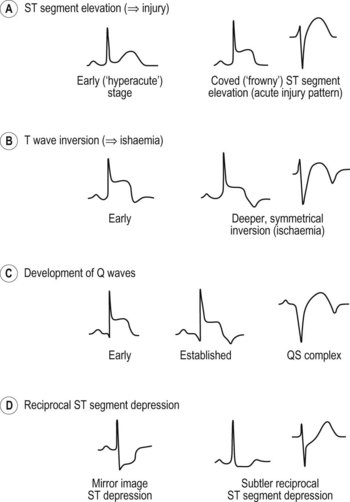

How would you use the ECG to localize STEMI?

• Anterior or anteroseptal: The QS complexes in leads V1 and V2 indicate anteroseptal infarction. A characteristic notching of the QS complex, often seen with infarcts, is present in lead V2. The septum is supplied with blood by the left anterior descending coronary artery. Septal infarction generally suggests this artery or one of its branches is occluded, whereas a strictly anterior infarct generally results from occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

• Anterolateral: ST segment elevation in leads I, L, and V1 to V6 with Q waves in V1 to V4. (Fig. 14.1B,C)

• Posterior: tall R waves in leads V1 and V2. In most cases of posterior infarctions, the infarct extends either to the lateral wall of the LV (resulting in characteristic changes in lead V6) or to the inferior wall of that ventricle (resulting in characteristic changes in leads II, III and aVF). Because of the overlap between inferior and posterior infarctions, the more general term inferoposterior is used when the ECG shows changes consistent with either inferior or posterior infarction.

• Inferior: ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF and the reciprocal ST depressions in leads I and aVL. Inferior wall infarction is generally caused by occlusion of the right coronary artery. Less commonly, it occurs because of a left circumflex coronary obstruction.

• Right ventricular infarction: Q waves and ST segment elevations in leads II, III and aVF are accompanied by ST elevations in the right precordial leads.

This classification is not absolute, and infarct types often overlap.

How would you manage a patient with acute MI?

• In A&E, a patient with chest pain should have a quick clinical examination and an ECG done within 10 min of arrival to hospital.

• Aspirin: chewable non-coated 160–325 mg should be administered immediately and then 160–325 mg daily. In the ISIS-2 and ISIS-3 trials, 160 mg dosage was effective whereas a 325 mg dose was used successfully in GISSI-2. An initial large dose of aspirin of 325 mg orally or 160 mg chewable aspirin is preferred because lower doses may still allow significant thromboxane activity and may take a few days.

• Pain relief: immediate relief of pain should be a top priority because severe pain can result in autonomic disturbances that can result in sudden death.

• Reperfusion strategies: either thrombolysis or primary PTCA should be performed within 30 min of the patient’s arrival in hospital.

• Beta-blockers: patient should receive beta-blockers when there are no contraindications within 12 h of onset of infarction, irrespective of administration of concomitant thrombolytic therapy or performance of primary angioplasty.

• ACE inhibitors: should be administered within the first 24 h of a suspected acute STEMI in ≥2 anterior precordial leads or with clinical heart failure in the absence of hypotension (systolic BP <100 mmHg) and known contraindications to use of ACE inhibitors.

What are the complications of myocardial infarction?

• Extension of infarct and post-infarct ischaemia

• Rhythm disorders: tachycardia, bradycardia, ventricular ectopics, ventricular fibrillation, atrial fibrillation and tachycardia

• Heart failure: acute pulmonary oedema

• Circulatory failure: cardiogenic shock

• Infarction of papillary muscle: mitral regurgitation and acute pulmonary oedema

• Rupture of interventricular septum

• Thromboembolism, cerebral or peripheral

• Dressler syndrome: characterized by persistent pyrexia, pericarditis, pleurisy (first described in 1956 when Dressler recognized that chest pain following MI is not caused by coronary artery insufficiency).

How is short-term risk determined in acute coronary syndromes?

The TIMI risk score can be used for unstable angina/NSTEMI and for STEMI.

Unstable angina/NSTEMI

• >3 risk factors for coronary artery disease

• Documented coronary artery disease at catheterization

What are TIMI grades?

0: no flow of contrast beyond the point of occlusion

1: penetration with minimal perfusion (contrast fails to opacify the entire coronary bed distal to the stenosis for the duration of investigation)

2: partial perfusion (contrast opacifies the entire distal coronary artery, but the rate of entry or clearance or both is slower in the previously blocked artery than in nearby normally perfused vessels

3: complete perfusion (contrast filling and clearance are as rapid in the previously blocked vessel as in normally perfused vessels).

Which thrombolytic agents are available?

• Streptokinase: for non-anterior MI

• Tenecteplase: for anterior MI, previous streptokinase use, systolic BP <100 mmHg, new left bundle branch block; can be given by paramedics and administered as a bolus

• Alteplase (rt-PA): in younger patients with anterior MI; given within 6 h of symptoms in accelerated manner and followed by heparin

What is the relation between thrombolysis and onset of symptoms?

| Duration from symptom onset to therapy initiation | Lives saved per 1000 treated |

|---|---|

| <60 min | 65 |

| 2–3 h | 27 |

| 4–6 h | 25 |

| 7–12 h | 8 |

What is the role of primary angioplasty in acute infarction?

• Angioplasty results in both lower mortality rates and reduction in the incidence of recurrent ischaemic events. Also angioplasty is associated with lower enzyme rise, better left ventricular function and less reinfarction. Angioplasty led to shorter hospital stay, fewer re-admissions and lower follow-up costs. However, the major limitation of this approach is the access to both facilities and personnel to carry out the procedure.

• Angioplasty should be considered in patients who have recognized contraindication to thrombolysis (even if this means transferring the patient) or who are considered high risk and present with their infarction to a hospital where angioplasty can be performed. Patients who have received thrombolysis and who seem on clinical grounds (reduction in maximal ST segment elevation by 50% and resolution of chest pain) not to have reperfused at 90 min review should be seriously considered for rescue angioplasty, again even if this means transferring the patient.

• Patients who do not receive reperfusion therapy should be treated immediately with fondaparinux.

What is the role of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists as adjuncts to thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction?

What do you know about risk stratification after myocardial infarction?

• Risk stratification before hospital discharge is an important aspect of management and determines whether coronary angiography is indicated. The first step is to determine whether the clinical variables indicating a relatively high risk for future cardiac events are present:

• Patients without these clinical indicators of high risk should undergo an assessment of left ventricular function (echocardiogram or radionuclide angiogram and submaximal stress) before hospital discharge:

• In patients in whom the ECG is not interpretable because of resting ST–T wave abnormalities, digitalis therapy or left bundle branch block, rest and exercise radionuclide myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (with thallium or sestamibi) or rest and exercise echocardiography should be performed. Patients who cannot exercise should undergo pharmacologic stress imaging study such as adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion scintigraphy or echocardiography with dobutamine or dipyridamole stress. A marked abnormality in any of these tests or a resting ejection fraction <40%, measured by echocardiography or a radionuclide technique, should be followed by coronary angiography.

How is non-invasive testing used to risk stratify patients?

Risk stratification based on non-invasive testing (J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:2092–197) comprises:

High risk (>3% annual mortality rate):

• Severe resting LV dysfunction (LV ejection fraction <35%)

• High-risk treadmill score (score ≥−11)

• Severe exercise LV dysfunction (exercise LV ejection fraction <35%)

• Stress-induced large perfusion defect (particularly if anterior)

• Stress-induced multiple perfusion defects of moderate size

• Large, fixed perfusion defect with LV dilation or increased lung uptake (thallium-201)

• Stress-induced moderate perfusion defect with LV dilation or increased lung uptake (thallium-201)

• Echocardiographic wall motion abnormality (involving >2 segments) developing at a low dose of dobutamine (%10 mg/min per kg) or at a low heart rate (<120 beats/min)

Intermediate risk (1–3% annual mortality rate):

• Mild/moderate resting LV dysfunction (LV ejection fraction 35–49%)

• Intermediate-risk treadmill score (−11 to <5)

• Stress-induced moderate perfusion defect without LV dilation or increased lung intake (thallium-201)

• Limited stress echocardiographic ischaemia with a wall motion abnormality only at higher doses of dobutamine involving >2 segments.

What advice would you give this patient on discharge?

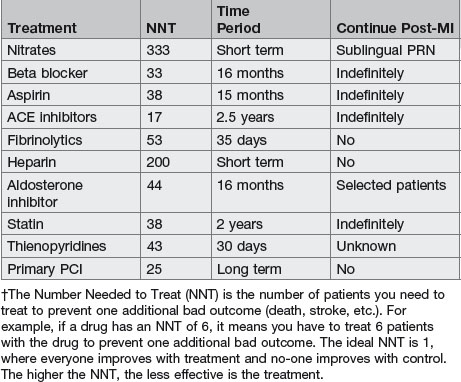

Secondary prevention of myocardial infarction (BMJ 1998;316:838–42) as follows:

• Smoking cessation: it should be emphasized to the patient that within 2 years of discontinuing smoking, the risk of a non-fatal recurrent MI falls to the level observed in a patient who has never smoked.

• Lipid profile: a lipid profile should be obtained in all patients with acute MI. Since cholesterol may fall after 24 to 48 h, it is important these measurements be obtained on admission; otherwise a 6-week wait is necessary for cholesterol to reach pre-MI levels. It is desirable to fractionate the cholesterol, and patients with LDL cholesterol >3.37 mmol/l should be treated with lipid lowering agents (p. 616).

• Cardiac rehabilitation: all discharged patients should be referred for outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Patients should be encouraged to increase activity gradually over 1–2 months.

• Risk factors: diabetes (target HbA1C <6) and hypertension (target BP <130/85 mmHg) should be aggressively controlled.

• Aspirin: led to a 12% reduction in death, a 31% reduction in re-infarction and a 42% reduction in non-fatal stroke in a study of 19791 patients who had myocardial infarctions reviewed by the Antiplatelet Therapy Trialists. Low to medium doses (75–325 mg/day) seems to be as effective as high doses (1200 mg/day).

• Beta-blockers: several controlled trials in >35000 survivors of MI have shown the benefit of long-term treatment with beta-blockers in reducing the incidence of recurrent MI, sudden death and all cause mortality. Beta-blockers reduce myocardial workload and oxygen consumption by reducing the heart rate, BP and contractility, and they increase the threshold for ventricular fibrillation. The beneficial effect of beta-blockers seems to be a class effect, but those with agonist activity do not show a beneficial effect on mortality, and their use cannot be recommended at present.

• ACE inhibitors: low-dose ramipril should be considered in all patients with uncomplicated MI (N Engl J Med 2000;342:145–53). Treatment with full dose ACE inhibitors is recommended for an indefinite period in all patients with congestive heart failure, an ejection fraction <40% or a large regional wall motion abnormality.