Chapter 47 ACUTE LIVER FAILURE

DEFINITION

ALF is a broad term encompassing both fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) and subfulminant hepatic failure (or late-onset hepatic failure). FHF is generally used to describe the development of encephalopathy within 8 weeks of the onset of symptoms in a patient with a previously healthy liver. Subfulminant hepatic failure refers to patients with liver disease for up to 26 weeks prior to the development of hepatic encephalopathy. Some patients with previously unrecognised chronic liver disease decompensate and present with liver failure; although this is not technically FHF, discriminating this at the time of presentation may not be possible.

CAUSES OF ACUTE LIVER FAILURE

Idiosyncratic drug toxicity

A variety of prescription drugs, including various antiepileptics (e.g. phenytoin, sodium valproate), non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (e.g. diclofenac) and antibiotics (e.g. isoniazid) have been implicated in acute liver failure (Table 47.1). Most cases occur within the first 4–6 weeks of initiating treatment, but can occur years after the drug is commenced. Certain herbal preparations and other nutritional supplements have been found to cause liver injury. In addition, a variety of illicit substances, including synthetic amphetamines, have been linked to ALF.

| Drug toxicity |

HELLP syndrome = haemolysis elevated liver enzymes low platelet syndrome.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis A virus and hepatitis B virus are the chief causes of ALF in India and other parts of the developing world. However, ALF is an uncommon complication of viral hepatitis, occurring in 0.2%–4% of cases depending on the underlying aetiology. The risk of developing ALF from hepatitis E approaches 20% in pregnant women. Other viral aetiologies of ALF include hepatitis D virus coinfection or superinfection (Table 47.1), Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster.

Miscellaneous

There are a number of other less common causes of ALF. Pregnancy-related liver disease may result in ALF, usually in the third trimester. A variety of presentations may be seen with thrombocytopenia and features of pre-eclampsia often present. Wilson’s disease may present as ALF, typically in young patients accompanied by the abrupt onset of haemolytic anaemia. The fulminant presentation carries a poor prognosis without transplantation. Autoimmune hepatitis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, toxins (mushroom poisoning, aflatoxins), ischaemic hepatitis and malignant infiltration of the liver are other infrequent causes of ALF (Table 47.1). A definite cause is unable to be identified in approximately 15%–40% of cases of ALF worldwide.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND MAJOR COMPLICATIONS

Coagulopathy and bleeding

Patients with ALF have a prolonged prothrombin time primarily because of decreased synthesis of clotting factors. Increased consumption of clotting factors and platelets may also occur, and platelet levels are often <100,000/mm3. Clinically significant bleeding has been reported to occur in up to 20% of patients with ALF. The most common sources include the upper gastrointestinal tract, nasopharynx and skin puncture sites.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND PROGNOSIS

History taking should address possible exposure to viral infection and drugs (including herbal medications and other nutritional supplements) or other toxins; collateral history from family members is often necessary. It is also important to ask about the date of onset of jaundice and encephalopathy. Physical examination must include careful assessment and documentation of mental status and a search for stigmata of chronic liver disease (which should be absent). Jaundice is often, but not always, present. Right upper quadrant tenderness is variably present. Liver size may be small, indicating a loss of volume due to hepatic necrosis. Hepatomegaly should raise suspicion of viral hepatitis, malignant infiltration, congestive heart failure or acute Budd-Chiari syndrome. Patients frequently present with hypotension and tachycardia, which results from the reduced systemic vascular resistance accompanying FHF.

In patients with Wilson disease, FHF is almost uniformly fatal without liver transplantation.

Rate of development and degree of encephalopathy is a useful predictor of outcome; a short time from jaundice (usually the first unequivocal sign of liver disease recognised by the patient or family) to encephalopathy is paradoxically associated with improved survival. When this interval is less than 2 weeks, the patient has hyperacute liver failure.

MANAGEMENT

General measures

For those patients with ALF in whom no aetiology-specific therapy exists, treatment is limited to general supportive measures that anticipate and manage complications, allowing the liver time to regenerate. Patients with altered mentation should generally be admitted to an intensive care unit. These patients can deteriorate rapidly and require constant monitoring; early consideration of transfer to a transplant centre is important, as worsening encephalopathy increases the risk involved with transfer and may even preclude transfer. Specific criteria have been developed to guide decisions regarding transfer to a specialist liver transplant unit. Management issues relating to the most common complications seen in patients with ALF are outlined below.

Multiorgan failure syndrome

Hypotension resulting from volume depletion should be treated with blood or colloids. Care must be taken to avoid exacerbation of cerebral oedema with aggressive fluid replacement; a central venous catheter may be useful for monitoring intravascular volume status. Vasopressor agents may be required for reduced systemic vascular resistance. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are often required for respiratory depression due to coma or impaired gas exchange resulting from pulmonary sepsis or ARDS. Renal function should be optimised by maintaining adequate haemodynamics while avoiding nephrotoxic medications and contrast agents. Dialysis support is sometimes required, with continuous venovenous haemofiltration preferred over intermittent modalities.

Liver transplantation

The advent of orthotopic liver transplantation has dramatically improved overall survival rates for patients with ALF from less than 30% in the pre-transplant era to more than 60% presently. Post-transplant survival rates for ALF have been reported to be as high as 80%–90%. In the patient with ALF being considered for transplantation (Table 47.2), the likelihood of spontaneous recovery must be balanced against the risks of surgery and longterm immunosuppression. Approximately 40%–50% of patients with ALF will undergo transplantation. Despite the urgent listing assigned to these patients, a significant proportion will die on the waiting list or develop complications precluding transplantation due to a critical ongoing shortage of donor organs. Some centres utilise artificial liver support systems, although this is still considered experimental.

TABLE 47.2 King’s College criteria for liver transplantation in acute liver failure

| Paracetamol (acetaminophen) cases | Non-paracetamol (non-acetaminophen) cases |

INR = international normalised ratio.

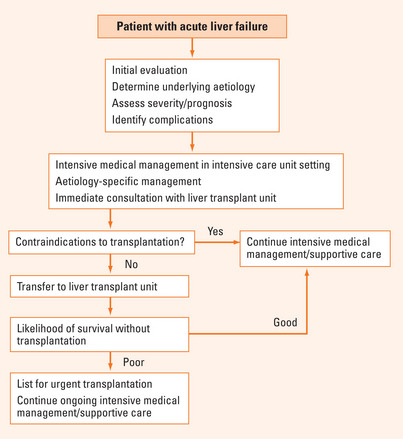

A general approach to the management of patients with ALF is represented in Figure 47.1.

SUMMARY

ALF is a term that encompasses both fulminant hepatic failure and subfulminant hepatic failure. It is defined as the rapid development of coagulopathy and encephalopathy in a patient with deteriorating liver function tests with no underlying liver disease. The most common causes include drug toxicity, acute viral hepatitis and pregnancy-related liver conditions. Patients may present with hepatic encephalopathy, coagulopathy, multiorgan failure and a variety of significant metabolic disturbances. Superimposed systemic infections often complicate the clinical scenario. Patients always require urgent evaluation and management, with the initial evaluation aimed at determining the underlying cause, assessing the severity of the illness and identifying complications. Such presentations necessitate intensive medical management. A high awareness of the need for early liver transplantation is warranted. Acute liver failure is associated with a high mortality rate, but with the advent of liver transplantation the overall survival rates are now greater than 60%.

Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure. In: Feldman M, editor. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:1993-2006.

Gill RQ, Sterling RK. Acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:191-198.

O’Grady JG. Acute liver failure. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:148-154.

Polsen J, Lee WM. AASLD position paper: The management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179-1197.

Sass DA, Shakil AO. Fulminant hepatic failure. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:594-605.