Problem 24 Acute leg pain in a 73-year-old man

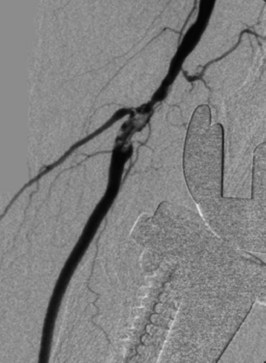

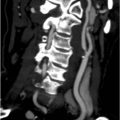

An investigation is performed. One of the results is shown in Figure 24.1.

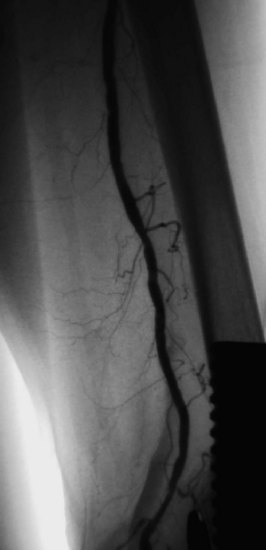

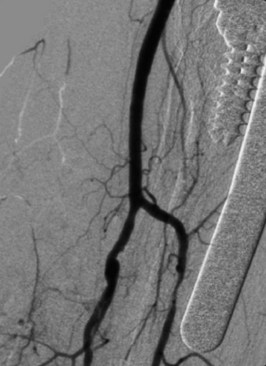

The patient underwent thrombolysis of the embolus radiologically using the ‘pulse-spray’ technique that often results in rapid clot lysis. Standard thrombolytic techniques would take 4–20 hours to achieve clot dissolution, and it was thought this patient’s leg was unlikely to be viable if revascularization took this length of time. The ‘pulse-spray’ technique is much more rapid. After 1 hour of urokinase pulsing, the angiogram was repeated (Figures 24.2 and 24.3).

Answers

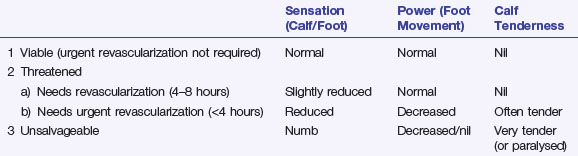

A.5 This patient has a threatened ischaemic leg requiring revascularization within 4 hours (see Revision points at end of chapter).

Revision Points

Acute Lower Limb Ischaemia

Aetiology

Investigations

Management

Therapy will depend on aetiology, severity of ischaemia and patient co-morbidities.

Norgen L., Hiatt W.R., Dormandy J.A., et alTASC II Working Group. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2007;45:S1-S67.

Ouriel K. Thrombolytic therapy for acute arterial occlusion. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2002;194:S32-S39.