Chapter 34 ACUTE HEPATITIS

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Most cases of acute hepatitis are caused by viral hepatitis. Systemic infections such as pneumonia are also commonly associated with non-specific and reactive hepatitis. A smaller cohort is associated with drugs, vascular abnormalities, metabolic disturbance, autoimmunity, pregnancy and systemic illness, such as cardiogenic shock and metabolic disturbance (Table 34.1). However, in fulminant hepatic failure or subfulminant hepatic failure, drugs can become a dominant cause of acute hepatitis. The scope of this chapter will focus primarily on acute viral hepatitis.

| Viral hepatitis |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical spectrum of acute hepatitis may range from mild symptoms and signs (Table 34.2) associated with recent onset of liver enzyme abnormalities to fulminant hepatic failure. Most symptoms and signs are non-specific (Table 34.2) though there are some manifestations associated with specific conditions, and if present, are helpful in differential diagnosis (Table 34.3).

TABLE 34.2 Non-specific symptoms and signs of acute hepatitis

TABLE 34.3 Diagnostically helpful associations of acute hepatitis

| Infectious mononucleosis | Hepatitis C |

| Metabolic disturbance | |

| Hepatitis B | Drugs |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

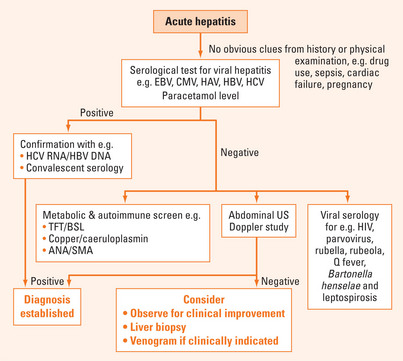

A diagnostic algorithm is suggested for assessing a patient presenting with acute hepatitis (Figure 34.1). There may be obvious clues at the outset such as pregnancy, history of paracetamol overdose or recent drug use. Serology for common causes of viral hepatitis and paracetamol level should be requested as initial investigations. Failing to identify an obvious cause, other less common causes would need to be considered and liver biopsy may be necessary.

Acute viral hepatitis

The most common cause of acute hepatitis found on audits of consecutive presentations to the emergency department is hepatitis B, followed by hepatitis A and C (Table 34.4). History of travel, family contacts, immunocompetency, blood transfusions, intravenous (IV) drug usage, sexual practice, tattoos, body piercing, birthplace and prior vaccination can provide useful information for differential diagnosis.

| Western countries | |

| Acute hepatitis B | 30%–60% |

| Hepatitis A | 25%–50% |

| Acute hepatitis C | 15%–20% |

| EBV hepatitis | 2%–10% |

| Hepatitis G | 1% |

| CMV hepatitis | 1% |

| Asian countries | |

| Acute hepatitis B | 5%–13% |

| Acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B | 15%–40% |

| Acute hepatitis C | 21% |

| Acute hepatitis C in hepatitis B carriers | 12% |

| Hepatitis A | 3%–4% |

| Hepatitis E | 2%–70%* |

| Hepatitis A, D, E in hepatitis B carriers | 20% |

| Non A–E hepatitis | 16% |

| Superimposed non A–E hepatitis in hepatitis B carriers | 15% |

CMV = cytomegalovirus; EBV = Epstein-Barr virus.

* There is significant geographical variability with the higher proportion of hepatitis E virus accounting for presentation of acute hepatitis reported in India.

The geographic differences in the prevalence of acute viral hepatitis also need to be borne in mind in differential diagnosis. In Western countries, most cases of hepatitis B and C are acquired as an adult through sexual transmission or drug use. Hepatitis E is unusual in Western countries but common in the Indian subcontinent (Table 34.4). On the other hand, in Asian countries, notably Taiwan, almost half the cases are represented by hepatitis B carriers presenting either with an exacerbation of hepatitis B infection or with superimposed non-B hepatotropic viral infections (Table 34.4).

Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis

Of patients with EBV infection, 80%–90% have mild hepatic parenchymal injury with most expected to resolve spontaneously. Rarely, it could manifest as cholestatic hepatitis, progress to chronic hepatitis or fulminant hepatic failure. Most cases of fatality are associated with immunodeficiency. Hence, depending on the age of the patient, testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease and complement deficiency should be considered in those presenting with fulminant hepatitis.

Laboratory investigations

| Atypical lymphocytes | Not pathognomonic |

| May be found in toxoplasmosis, rubella, roseola and CMV | |

| Lymphocytosis | Usually 12–18 × 109/L |

| Heterophile antibody | Detectable within 1 week of symptoms Sensitivity 70%–92% and specificity 96%–100% |

| EBV IgM | Directed at the viral capsid antigen, early antigen and anti-EBV nuclear antigen |

Cytomegalovirus infection

Laboratory Investigations

| Atypical lymphocytosis | Not pathognomonic |

| CMV IgM | False positive may be associated with pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome and antinuclear antibody (ANA)-positive patients |

Hepatitis A

Laboratory investigations

| HAV IgM | Confirms acute HAV infection Peak during the acute phase of infection |

| Undetectable after 3–4 months although 25% may have IgM persistence up to 6 months or more | |

| HAV IgG | Indicates previous exposure and immunity to hepatitis A |

| Rising HAV IgG levels is indicative of recent exposure | |

| HAV RNA | Not clinically useful as the virus is usually undetectable at the time of clinical manifestation |

Hepatitis B

This infection is discussed in more detail in Chapter 36. Acute infection in immunocompetent adults is often self-limiting. Fulminant hepatitis is rare but associated with a poor prognosis. Individuals at risk of chronicity include those who acquired hepatitis perinatally or those with HIV coinfection. Acute hepatitis B infection may be associated with a number of extrahepatic manifestations including polyarteritis nodosa, vasculitisinduced neuropathy, renal disease, rash, arthritis and Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Laboratory investigations

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Marker of hepatitis B infection |

| Hepatitis B surface antibody | Detection in the presence of hepatitis B core IgG indicates resolution of hepatitis B infection and immunity |

| Detection in the absence of hepatitis B core IgG indicates immunity from past vaccination | |

| Hepatitis B core IgM | Detectable with the onset of symptoms during acute infection for up to 6 months |

| Not able to distinguish between acute infection and a flare as it may also reappear in chronic carriers during a severe flare | |

| Hepatitis B core IgG | Often persists for a lifetime and therefore the best marker of exposure to hepatitis B |

| Hepatitis B e antigen | Marker of viral replication of wild type hepatitis B |

| HBV DNA | Marker of viral replication |

| Threshold of detection varies with different assays, being the most sensitive with Taqman fluorescent-probe real time PCR at 10 copies/mL |

Hepatitis D

Coinfection of hepatitis D and B is often self-limiting, characterised by a biphasic increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and associated with higher risk of severe or fulminant hepatitis than hepatitis B infection alone. Acute superinfection of hepatitis D in established hepatitis B-infected patients may lead to a flare, which results in clearance of both infections. Chronic superinfection of hepatitis D is thought to hasten disease progression in a subgroup of hepatitis B-infected patients.

Laboratory investigations

| HDV IgM | Associated with detectable hepatitis B core IgM in coinfected patients and the absence of hepatitis B core IgM in superinfection |

| HDV antigen | Often transiently detectable in low titres during late incubation phase and therefore of little clinical utility |

| HDV RNA | Not routinely available |

Drug-induced hepatitis

Drug-induced liver injury accounts for less than 5% cases of acute hepatitis. Most cases are self-limiting upon withdrawal of the offending drug. However, rarely, some may develop chronicity associated with cirrhosis or vascular complications. Other cases progress to fulminant hepatitis with hepatic failure. Some agents may present with a hepatocellular pattern while others may become predominantly cholestatic.

Ater MJ, Gallagher M, Morris TT, et al. Acute non A-E hepatitis in the United States and the role of hepatitis G virus infection. Sentinel Counties Viral Hepatitis Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:741-746.

Crum N. Epstein Barr virus hepatitis: case series and review. South Med J. 2006;99:544-547.

Watanabe S, Arima K, Nishioka M, et al. Comparison between sporadic cytomegalovirus hepatitis and Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis in previously healthy adults. Liver. 1997;17:63-69.