Chapter 332 Acute Gastroenteritis in Children

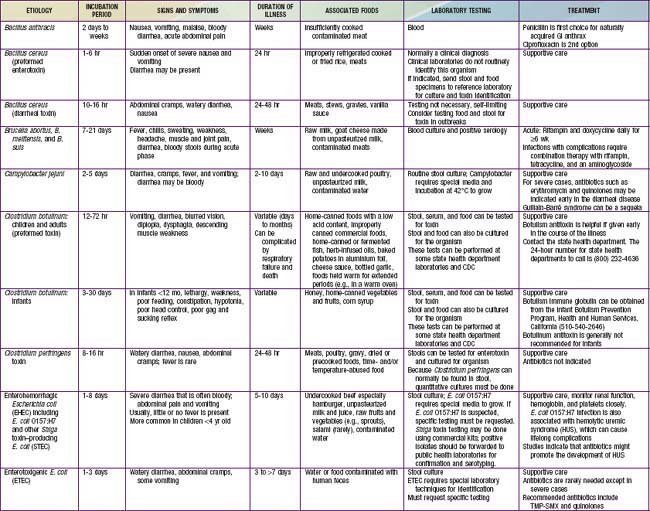

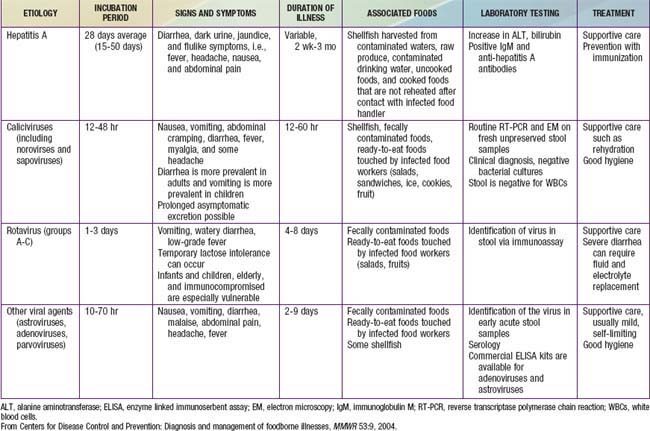

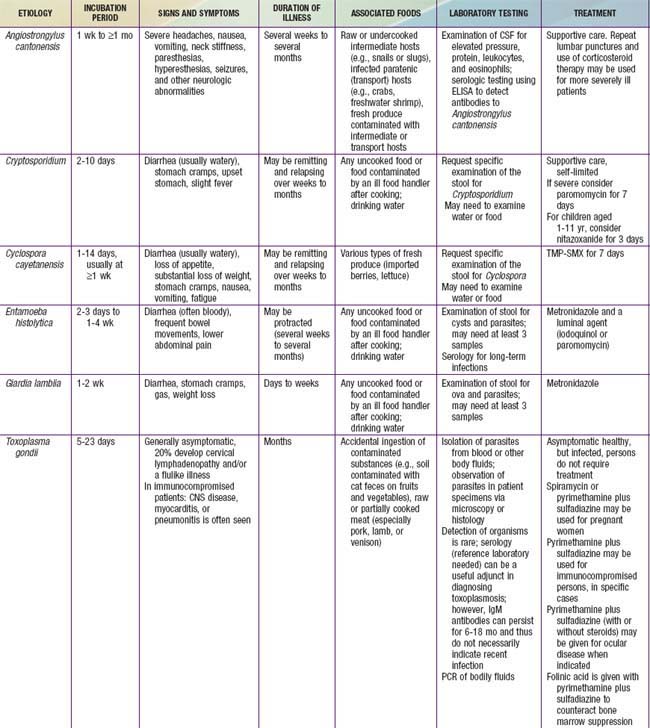

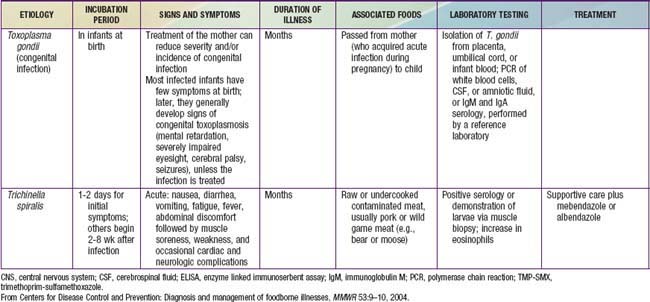

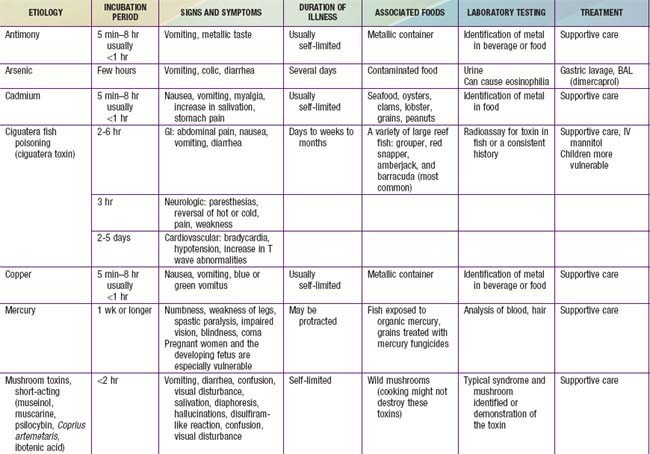

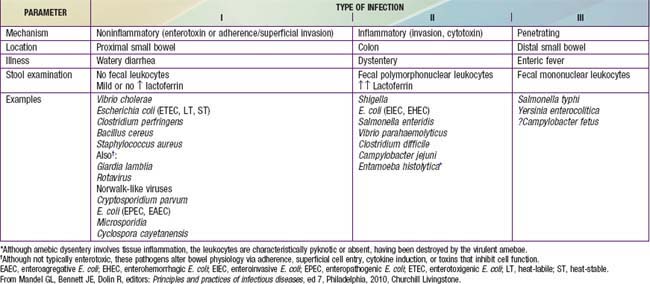

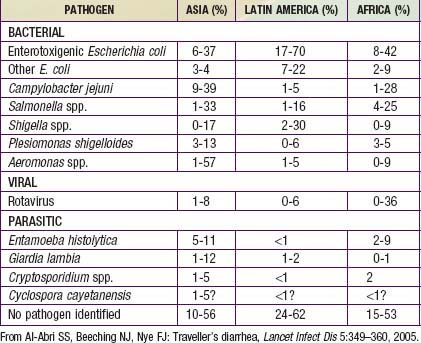

The term gastroenteritis denotes infections of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract caused by bacterial, viral, or parasitic pathogens (Tables 332-1 to 332-3). Many of these infections are foodborne illnesses. The most common manifestations are diarrhea and vomiting, which can also be associated with systemic features such as abdominal pain and fever. The term gastroenteritis captures the bulk of infectious cases of diarrhea. The term diarrheal disorders is more commonly used to denote infectious diarrhea in public health settings, although several noninfectious causes of GI illness with vomiting and/or diarrhea are well recognized (Table 332-4).

Epidemiology of Childhood Diarrhea

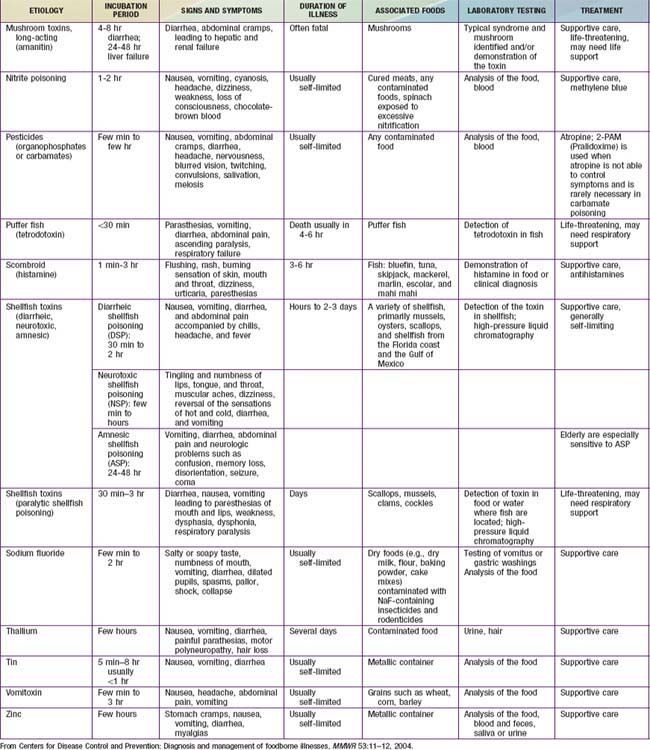

Diarrheal disorders in childhood account for a large proportion (18%) of childhood deaths, with an estimated 1.5 million deaths per year globally, making it the second most common cause of child deaths worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF estimate that almost 2.5 billion episodes of diarrhea occur annually in children <5 yr of age in developing countries, with more than 80% of the episodes occurring in Africa and South Asia (46% and 38%, respectively). Global mortality may be declining, but the overall incidence of diarrhea remains unchanged at about 3.6 episodes per child-year (Fig. 332-1), and it is estimated to account for 13% of all childhood disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

Etiology of Diarrhea

Gastroenteritis is due to infection acquired through the fecal-oral route or by ingestion of contaminated food or water. Gastroenteritis is associated with poverty, poor environmental hygiene, and development indices. Enteropathogens that are infectious in a small inoculum (Shigella, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, Campylobacter jejuni, noroviruses, rotavirus, Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, Entamoeba histolytica) can be transmitted by person-to-person contact, whereas others, such as cholera, are generally a consequence of contamination of food or water supply (see Tables 332-1 to 332-3).

In the United States, rotavirus and the noroviruses (small round viruses such as Norwalk-like virus and caliciviruses) are the most common viral agents, followed by sapovirus, enteric adenoviruses, and astroviruses (see Table 332-2). Food-borne outbreaks of bacterial diarrhea in the United States are most commonly due to Salmonella, E. coli, Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus followed much less often by Campylobacter, Shigella, Cryptosporidium, Yersinia, Listeria, Vibrio, and Cyclospora species, in that order. Salmonella, Shigella, and, most notably, the various diarrhea-producing E. coli organisms are the most common bacterial pathogens in developing countries (see Table 332-1). Clostridium difficile (by toxin production) is linked to antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis, although most cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children are not due to C. difficile. C. difficile-negative antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis in adults may be due to cytotoxin-producing Klebsiella oxytoca. Waterborne outbreaks are often due to Cryptosporidium species (most common), C. jejuni, noroviruses, Shigella species, Giardia, E. coli O157:H7, Plesiomonas shigelloides, or Vibrio species.

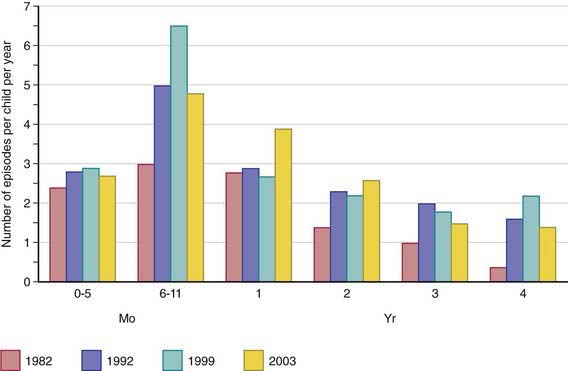

Pathogenesis of Infectious Diarrhea

Pathogenesis and severity of bacterial disease depend on whether organisms have preformed toxins (S. aureus, Bacillus cereus), produce secretory (cholera, E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella) or cytotoxic (Shigella, S. aureus, Vibrio parahemolyticus, C. difficile, E. coli, C. jejuni) toxins or are invasive and on whether they replicate in food. Enteropathogens can lead to either an inflammatory or noninflammatory response in the intestinal mucosa (Table 332-5).

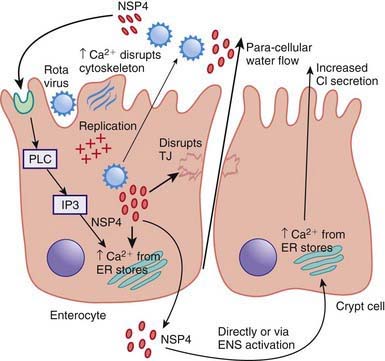

Enteropathogens elicit noninflammatory diarrhea through enterotoxin production by some bacteria, destruction of villus (surface) cells by viruses, adherence by parasites, and adherence and/or translocation by bacteria. Inflammatory diarrhea is usually caused by bacteria that directly invade the intestine or produce cytotoxins with consequent fluid, protein, and cells (erythrocytes, leukocytes) that enter the intestinal lumen. Some enteropathogens possess >1 virulence property. Some viruses, such as rotavirus, target the microvillus tips of the enterocytes and can enter the cells by direct invasion or calcium-dependent endocytosis. This can result in villus shortening and loss of enterocyte absorptive surface through cell shortening and loss of microvilli (Fig. 332-2).

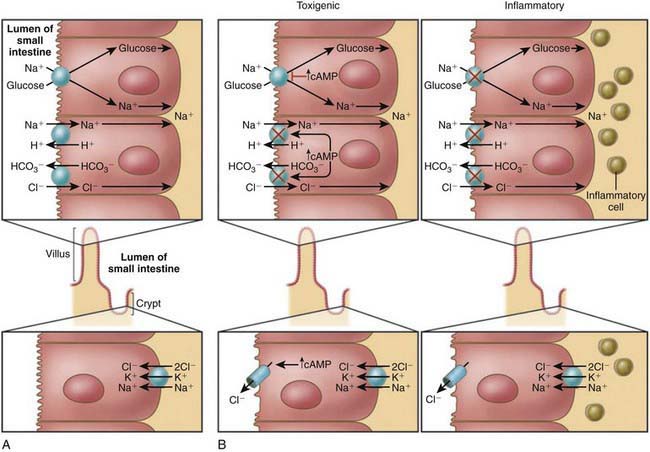

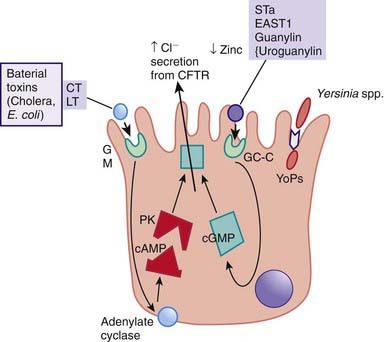

Most bacterial pathogens elaborate enterotoxins; the rotavirus protein NSP4 acts as a viral enterotoxin. Bacterial enterotoxins can selectively activate enterocyte intracellular signal transduction and can also affect cytoskeletal rearrangements with subsequent alterations in the water and electrolyte fluxes across enterocytes. In toxigenic diarrhea enterotoxin produced by Vibrio cholerae, increased mucosal levels of cAMP inhibit electroneutral NaCl absorption but have no effect on glucose-stimulated Na+ absorption. In inflammatory diarrhea (e.g., Shigella spp. or Salmonella spp.) there is extensive histologic damage, resulting in altered cell morphology and reduced glucose-stimulated Na+ and electroneutral NaCl absorption. The role of 1 or more cytokines in this inflammatory response is critical. In secretory cells from crypts, Cl-secretion is minimal in normal subjects and is activated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in toxigenic and inflammatory diarrhea (Fig. 332-3).

Figure 332-3 Mechanism of cholera toxin.

(Adapted from Thapar M, Sanderson IR: Diarrhoea in children: an interface between developing and developed countries, Lancet 363:641–653, 2004; and Montes M, DuPont HL: Enteritis, enterocolitis and infectious diarrhea syndromes. In Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, et al, editors: Infections diseases, ed 2, London, 2004, Mosby, pp 31–52.)

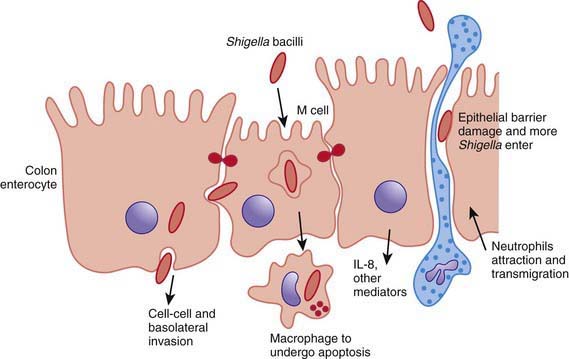

ETEC colonizes and adheres to enterocytes of the small bowel via its surface fimbriae (pili) and induces hypersecretion of fluids and electrolytes into the small intestine through 1 of 2 toxins: the heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) or the heat-stable enterotoxin. LT is structurally similar to the V. cholerae toxin, and activates adenylate cyclase, resulting in an increase in intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Fig. 332-4). In contrast, Shigella spp. cause gastroenteritis via a superficial invasion of colonic mucosa, which they invade through M cells located over Peyer patches. After phagocytosis, a series of events occurs, including apoptosis of macrophages, multiplication and spread of bacteria into adjacent cells, release of inflammatory mediators (interleukin [IL]-1 and IL-8), transmigration of neutrophils into the lumen of the colon, neutrophil necrosis and degranulation, further breach of the epithelial barrier, and mucosal destruction (Fig. 332-5).

Clinical Manifestation of Diarrhea

Most of the clinical manifestations and clinical syndromes of diarrhea are related to the infecting pathogen and the dose or inoculum (see Tables 332-1 to 332-3). Additional manifestations depend on the development of complications (e.g., dehydration and electrolyte imbalance) and the nature of the infecting pathogen (see Table 332-5). Usually the ingestion of preformed toxins (e.g., those of S. aureus) is associated with the rapid onset of nausea and vomiting within 6 hr, with possible fever, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea within 8-72 hr. Watery diarrhea and abdominal cramps after an 8-16 hr incubation period are associated with enterotoxin-producing C. perfringens and B. cereus. Abdominal cramps and watery diarrhea after a 16-48 hr incubation period can be associated with noroviruses, several enterotoxin-producing bacteria, Cryptosporidium, and Cyclospora and have also been a notable feature of influenza virus H1N1 infections. Several organisms, including Salmonella, Shigella, C. jejuni, Yersinia enterocolitica, enteroinvasive or hemorrhagic (Shigatoxin-producing) E. coli, and V. parahaemolyticus, produce diarrhea that can contain blood as well as fecal leukocytes in association with abdominal cramps, tenesmus, and fever; these features suggest bacterial dysentery and fever (Table 332-6). Bloody diarrhea and abdominal cramps after a 72-120 hr incubation period are associated with infections due to Shigella and also Shigatoxin-producing E. coli, such as E. coli O157:H7. Organisms associated with dysentery or hemorrhagic diarrhea can also cause watery diarrhea alone without fever or that precedes a more complicated course that results in dysentery.

Table 332-6 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE DYSENTERY AND INFLAMMATORY ENTEROCOLITIS

SPECIFIC INFECTIOUS PROCESSES

PROCTITIS

OTHER SYNDROMES

CHRONIC INFLAMMATORY PROCESSES

SYNDROMES WITHOUT KNOWN INFECTIOUS CAUSE

From Mandel GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors: Principles and practices of infectious diseases, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2010, Churchill Livingstone.

Although many of the manifestations of acute gastroenteritis in children are nonspecific, some clinical features can help identify major categories of diarrhea and allow rapid triage for antibiotic or specific dietary therapy (see Tables 332-1 to 332-3). There is considerable overlap in the symptomatology. The positive predictive values for the features of dysentery are very poor; the negative predictability for bacterial pathogens is much better in the absence of signs of dysentery. If warranted and if facilities and resources permit, the etiology can be verified by appropriate laboratory testing.

Complications

Most of the complications associated with gastroenteritis are related to delays in diagnosis and delays in the institution of appropriate therapy. Without early and appropriate rehydration, many children with acute diarrhea would develop dehydration with associated complications (Chapter 54). These can be life-threatening in infants and young children. Inappropriate therapy can lead to prolongation of the diarrheal episodes, with consequent malnutrition and complications such as secondary infections and micronutrient deficiencies (iron, zinc). In developing countries and HIV-infected populations, associated bacteremias are well-recognized complications in malnourished children with diarrhea.

Specific pathogens are associated with extraintestinal manifestations and complications. These are not pathognomonic of the infection, nor do they always occur in close temporal association with the diarrheal episode (Table 332-7).

Table 332-7 EXTRAINTESTINAL MANIFESTATIONS OF ENTERIC INFECTIONS

| MANIFESTATION | ASSOCIATED ENTERIC PATHOGEN(S) | ONSET AND PROGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|

| Focal infections due to systemic spread of bacterial pathogens, including vulvovaginitis, urinary tract infection, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, peritonitis, chorioamnionitis, soft tissue infection, and septic thrombophlebitis | All major pathogens can cause such direct extraintestinal infections, including Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile | Onset usually during the acute infection, but can occur subsequently Prognosis depends on infection site |

| Reactive arthritis | Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Clostridium difficile | Typically occurs about 1-3 wk after infection Relapses after reinfection can develop in 15-50% of people but most children recover fully within 2-6 mo after the 1st symptoms appear |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | Campylobacter | Usually occurs a few weeks after the original infection Prognosis is good although 15-20% may have sequelae |

| Glomerulonephritis | Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia | Can be of sudden onset in acute, referring to a sudden attack of inflammation, or chronic, which comes on gradually In most cases, the kidneys heal with time |

| IgA nephropathy | Campylobacter | Characterized by recurrent episodes of blood in the urine, this condition results from deposits of the protein immunoglobulin A (IgA) in the glomeruli. IgA nephropathy can progress for years with no noticeable symptoms Men seem more likely to develop this disorder than women |

| Erythema nodosum | Yersinia, Campylobacter, Salmonella | Although painful, is usually benign and more commonly seen in adolescents Resolves with 4-6 wk |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Shigella dysenteriae 1, Escherichia coli O157:H7, others | Sudden onset, short-term renal failure In severe cases, renal failure requires several sessions of dialysis to take over the kidney function, but most children recover without permanent damage to their health |

| Hemolytic anemia | Campylobacter, Yersinia | Relatively rare complication and can have a chronic course |

From: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Managing acute gastroenteritis among children, MMWR Recomm Rep 53:1–33, 2004.

Diagnosis

Clinical Evaluation of Diarrhea

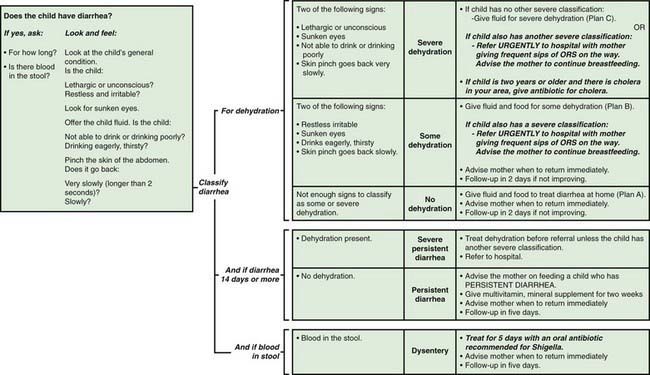

This clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of diarrhea in young children is a critical component of the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) package that is being implemented in developing countries with high burden of diarrhea mortality (Fig. 332-6).

Treatment

Oral Rehydration Therapy

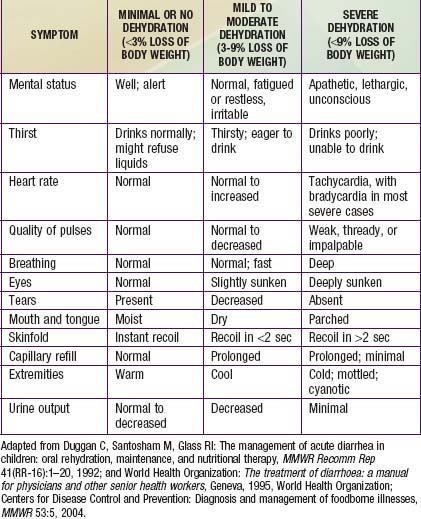

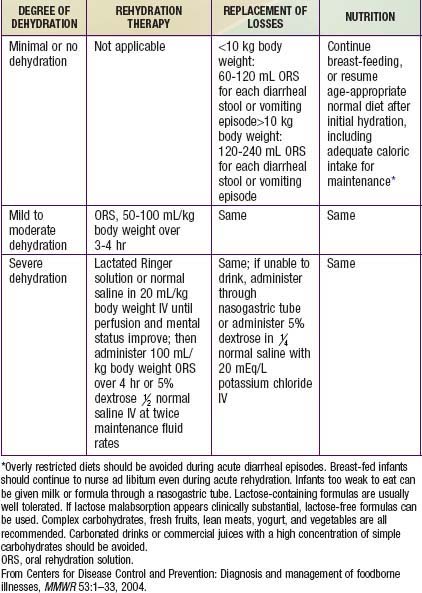

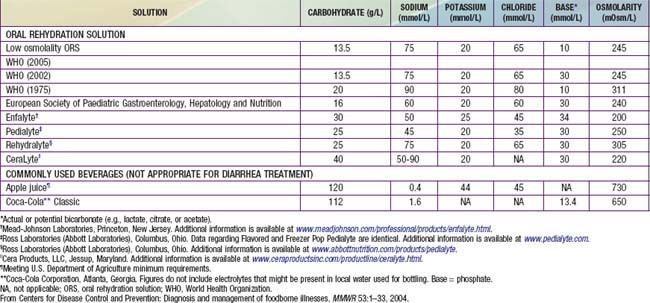

Children, especially infants, are more susceptible than adults to dehydration because of the greater basal fluid and electrolyte requirements per kg and because they are dependent on others to meet these demands. Dehydration must be evaluated rapidly and corrected in 4-6 hr according to the degree of dehydration and estimated daily requirements. A small minority of children, especially those in shock or unable to tolerate oral fluids, require initial intravenous rehydration, but oral rehydration is the preferred mode of rehydration and replacement of ongoing losses (see Tables 332-8 and 332-9). Risks associated with severe dehydration that might necessitate intravenous resuscitation include: age <6 mo, prematurity, chronic illness, fever >38°C if <3 mo or >39°C if 3-36 mo, bloody diarrhea, persistent emesis, poor urine output, sunken eyes, and a depressed level of consciousness. The low-osmolality WHO oral rehydration solution (ORS) containing 75 mEq of sodium and 75 mmol of glucose per liter, with total osmolarity of 245 mOsm per liter, is more effective than other formulations in reducing stool output without the risk of hyponatremia, and it is now the global standard of care (Table 332-10).

Cereal-based oral rehydration fluids can also be advantageous in malnourished children and can be prepared at home. Home remedies including decarbonated soda beverages, fruit juices, and tea are not suitable for rehydration or maintenance therapy because they have inappropriately high osmolalities and low sodium concentrations. A clinical evaluation plan and management strategy for children with moderate to severe diarrhea is outlined in Figure 332-6 and Table 332-9. Oral rehydration should be given to infants and children slowly, especially if they have emesis. It can be given initially by a dropper, teaspoon, or syringe, beginning with as little as 5 mL at a time. The volume is increased as tolerated. Replacement for emesis or stool losses is noted in Table 332-9. Oral rehydration can also be given by a nasogastric tube if needed; this is not the usual route.

Enteral Feeding and Diet Selection

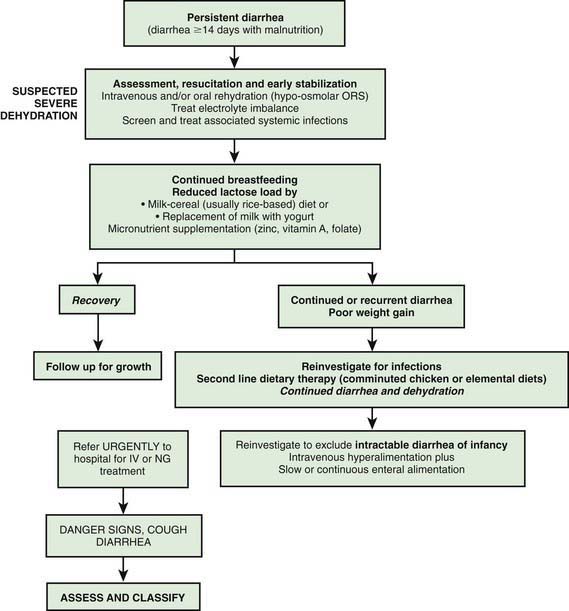

Rarely, when dietary intolerance precludes the administration of cow’s milk–based formulations or milk it may be necessary to administer specialized milk-free diets such as a comminuted or blenderized chicken-based diet or an elemental formulation. Although effective in some settings, the latter are unaffordable in most developing countries. In addition to rice-lentil formulations, the addition of green banana or pectin to the diet has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of persistent diarrhea. Figure 332-7 gives an algorithm for managing children with prolonged diarrhea in developing countries.

Antibiotic Therapy

Timely antibiotic therapy in select cases of diarrhea can reduce the duration and severity of diarrhea and prevent complications (Table 332-11). Although these agents are important to use in specific cases, their widespread and indiscriminate use leads to the development of antimicrobial resistance. Nitazoxanide, an anti-infective agent, has been effective in the treatment of a wide variety of pathogens including C. parvum, G. lamblia, E. histolytica, Blastocystis hominis, C. difficile, and rotavirus. Although preliminary data suggest that nitazoxanide may be of use in nonspecific acute secretory diarrhea, these data need replication in further studies.

| ORGANISM | DRUG OF CHOICE | DOSAGE AND DURATION OF TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Shigella (severe dysentery and EIEC dysentery) | Ciprofloxacin*, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, azit hromycin, or TMP-SMX Most strains are resistant now to several antibiotics |

Ceftriaxone 50-100 mg/kg/day IV or IM, qd or bid × 7 days Ciprofloxacin 20-30 mg/kg/day PO bid × 7-10 days Ampicillin PO, IV 50-100 mg/kg/day qid × 7 days |

| EPEC, ETEC, EIEC | TMP-SMX or ciprofloxacin* | TMP 10 mg/kg/day and SMX 50 mg/kg/day bid × 5 days Ciprofloxacin PO 20-30 mg/kg/day qid for 5-10 days |

| Salmonella | No antibiotics for uncomplicated gastroenteritis in normal hosts caused by non-typhoidal species Treatment indicated in infants <3 mo, and patients with malignancy, chronic GI disease, severe colitis hemoglobinopathies, or HIV infection, and other immunocompromised patients Most strains have become resistant to multiple antibiotics |

See treatment of Shigella |

| Aeromonas/Plesiomonas | TMP-SMX Ciprofloxacin* |

TMP 10 mg/kg/day and SMX 50 mg/kg/day bid for 5 days Ciprofloxacin PO 20-30 mg/kg/day divided bid × 7-10 days |

| Yersinia spp. | Antibiotics are not usually required for diarrhea Deferoxamine therapy should be withheld for severe infections or associated bacteremia Treat sepsis as for immunocompromised hosts, using combination therapy with parenteral doxycycline, aminoglycoside, TMP-SMX, or fluoroquinolone |

|

| Campylobacter jejuni | Erythromycin or azithromycin | Erythromycin PO 50 mg/kg/day divided tid × 5 days Azithromycin PO 5-10 mg/kg/day qid × 5 days |

| Clostridium difficile | Metronidazole (first line) | PO 30 mg/kg/day divided qid × 5 days; max 2 g |

| Discontinue initiating antibiotic | ||

| Vancomycin (2nd line) | PO 40 mg/kg/day qid × 7 days, max 125 mg | |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Metronidazole followed by iodoquinol or paromomycin | Metronidazole PO 30-40 mg/kg/day tid × 7-10 days Iodoquinol PO 30-40 mg/kg/day tid × 20 days Paromomycin PO 25-35 mg/kg/day tid × 7 days |

| Giardia lamblia | Furazolidone or metronidazole or albendazole or quinacrine | Furazolidone PO 25 mg/kg/day qid × 5-7 days Metronidazole PO 30-40 mg/kg/day tid × 7 days Albendazole PO 200 mg bid × 10 days |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Nitazoxanide PO treatment may not be needed in normal hosts In immunocompromised, PO immunoglobulin + aggressively treat HIV, etc. |

Children 1-3 yr: 100 mg bid × 3 days Children 4-11 yr: 200 mg bid |

| Isospora spp. | TMP-SMX | PO TMP 5 mg/kg/day and SMX 25 mg/kg/day, bid × 7-10 days |

| Cyclospora spp. | TMP/SMX | PO TMP 5 mg/kg/day and SMX 25 mg/kg/day bid × 7 days |

| Blastocystis hominis | Metronidazole or iodoquinol | Metronidazole PO 30-40 mg/kg/day tid × 7-10 days Iodoquinol PO 40 mg/kg/day tid × 20 days |

EIEC, Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; SMX, sulfamethoxazole; TMP, trimethoprim.

Prevention

Al-Abri SS, Beeching NJ, Nye FJ. Traveller’s diarrhoea. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:349-360.

Arvelo W, Hinkle J, Nguyen TA, et al. Transmission risk factors and treatment of pediatric shigellosis during a large daycare center–associated outbreak of multidrug resistant Shigella sonnei. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:976-980.

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417-440.

Bhutta ZA, Nelson EA, Lee WS, et al. Recent advances and evidence gaps in persistent diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:260-265.

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243-260.

Bryant K, McDonald LC. Clostridium difficile infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:145-146.

Cartwright RY. Food and waterborne infections associated with package holidays. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94:12S-24S.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated norovirus outbreak management and disease prevention guidelines. MMWR. 2011;60(3):1-15.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cryptosporidiosis surveillance—United States, 2006-2008 and giardiasis surveillance, United States 2006-2008. MMWR. 2010;59(SS-6):1-25.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple-serotype Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak after a reception—Connecticut, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(34):1093-1097.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli O157 infection associated with a day camp petting zoo—Pinellas County, Florida, May-June 2007. MMWR. 2009;58:426-428.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 2006. MMWR. 2009;58:609-614.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in children associated with raw milk and raw colostrum from cows—California, 2006. MMWR. 2008;57:625-628.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of cryptosporidiosis associated with a splash park—Idaho, 2007. MMWR. 2009;58:615-618.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Campylobacter jejuni infection associated with unpasteurized milk and cheese—Kansas, 2007. MMWR. 2009;57:1377-1380.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate outbreaks of Salmonella infections associated with live poultry—United States, 2007. MMWR. 2009:25-30.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections associated with peanut butter and peanut butter–containing products—United States, 2008–2009. MMWR. 2009;58:85-90.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate outbreak of human Salmonella typhimurium infections associated with pet turtle exposure—United States, 2008. MMWR. 2010;59:191-196.

Cortese MM, Parashar UD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. 2009;58:1-25.

Davies AP, Chalmers RM. Cryptosporidiosis. BMJ. 2009;339:963-967.

Denno DM, Stapp JR, Boster DR, et al. Etiology of diarrhea in pediatric outpatient settings. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:18-23.

DuPont HL. Bacterial diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1560-1569.

Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children. BMJ. 2007;334:35-40.

Finley R, Reid-Smith R, Weese JS. Human health implications of Salmonella-contaminated natural pet treat and raw pet food. CID. 2006;42:686-691.

Fischer Walker CL, Fontaine O, Young MW, et al. Zinc and low osmolarity oral rehydration salts for diarrhoea: a renewed call to action. Bull WHO. 2009;87:780-786.

Fonseca BK, Holdgate A, Craig JC. Enteral vs intravenous rehydration therapy for children with gastroenteritis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:483-490.

Fontaine O, Bhutta ZA, Bhatnagar S, et al. Directing diarrhoeal disease research towards disease-burden reduction. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:319-331.

Freedman SB, Adler M, Seshadri R, et al. Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1698-1705.

Freedman SB, Cho D, Boutis K, et al. Assessing the palatability of oral rehydration solutions in school-aged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(8):696-702.

Fullerton KE, Ingram A, Jones TF, et al. Sporadic Campylobacter infection in infants: a population-based surveillance case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:19-24.

Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1776-1784.

Goldman RD, Friedman JN, Parkin PC. Validation of the clinical dehydration scale for children with acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2008;122:545-549.

Goode B, O’Reilly C, Dunn J, et al. Outbreak of Escherichia coli O157. Arch Pediatr Adolecs Med. 2009;163:42-48.

Griffiths UK, Clark AD, Mullholland KM. Introduction of rotavirus vaccine. BMJ. 2009;339:b3482.

Guarino A, Lo Vecchio A, Canani RB. Probiotics as prevention and treatment for diarrhea. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:18-23.

Haider BA, Bhutta Z. The effect of therapeutic zinc supplementation among young children with selected infections: a review of the evidence. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30:S41-S59.

Harris JR, Bergmire-Sweat D, Schlegel JH, et al. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections associated with small turtle exposure, 2007–2008. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1388-1394.

Högenauer C, Langner C, Beubler E, et al. Klebsiella oxytoca as a causative organism of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2418-2426.

Huang DB, Awasthi M, Le B, et al. The role of diet in the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea: a pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:468-471.

Jalava K, Hakkinen M, Valkonen M, et al. An outbreak of gastrointestinal illness and erythema nodosum from grated carrots contaminated with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1209-1216.

Johnson S, Schriever C, Galang M, et al. Interruption of recurrent Clostridium difficile—associated diarrhea episodes by serial therapy with vancomycin and rifaximin. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:846-848.

Jones TF, Angulo FJ. Eating in restaurants: a risk factor for foodborne disease? Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1324-1328.

Junquera CG, Sainz de Baranda C, Mialdea OG, et al. Prevalence and clinical characterizations of norovirus gastroenteritis among hospitalized children in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:604-607.

Kelly CP, LaMont T. Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932-1940.

Khanna R, Lakhanpaul M, Burman-Roy S, et al. Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis in children under 5 years: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009;338:1009-1012.

Lazzerini M. Zinc supplements for severe cholera. BMJ. 2008;336:227-228.

Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Painter J, et al. Effect of intensive handwashing promotion on childhood diarrhea in high-risk communities in Pakistan. JAMA. 2004;291:2547-2554.

Lukacik M, Thomas RL, Aranda JV. A meta-analysis of the effects of oral zinc in the treatment of acute and persistent diarrhea. Pediatrics. 2008;121:326-336.

Lyman WH, Walsh JF, Kotch JB, et al. Prospective study of etiologic agents of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in child care centers. J Pediatr. 2009;154:253-257.

Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D, et al. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:289-298.

Maki DG. Coming to grips with foodborne infection—peanut butter, peppers, and nationwide Salmonella outbreaks. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:949-954.

Murphy MS. Management of bloody diarrhoea in children in primary care. BMJ. 2008;336:1010-1015.

Musher DM, Musher BL. Contagious acute gastrointestinal infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2417-2427.

Nelson EAS, Glass RI. Rotavirus: realizing the potential of a promising vaccine. Lancet. 2010;376:568-570.

O’Ryan M, Diaz J, Mamani N, et al. Impact of rotavirus infections on outpatient clinic visits in Chile. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:41-45.

Osterholm MT. Foodborne disease in 2011—the rest of the story. N Engl J Med. 2011;2364(10):889-891.

Parashar UD, Glass RI. Rotavirus vaccines—early success, remaining questions. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1063-1065.

Patel NC, Hertel PM, Estes MK, et al. Vaccine-acquired rotavirus in infants with severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:314-319.

Patro B, Szymanski H, Szajewska H. Oral zinc for the treatment of acute, gastroenteritis in Polish children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2010;157:984-988.

Payne DC, Parashar UD. Epidemiological shifts in severe acute gastroenteritis in US children: will rotavirus vaccination change the picture? J Pediatr. 2008;153:737-738.

Pfeil N, Uhug U, Kostev K, et al. Antiemetic medications in children with presumed infections gastroenteritis—pharmacoepidemiology in Europe and Northern America. J Pediatr. 2008;153:659-662.

Rabbani GH, Ahmed S, Hossain I, et al. Green banana reduces clinical severity of childhood shigellosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:420-425.

Ramani S, Kang G. Viruses causing childhood diarrhoea in the developing world. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:477-482.

Richardson V, Hernandez-Pichardo J, Quintanar-Solares M, et al. Effect of rotavirus vaccination on death from childhood diarrhea in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:299-305.

Rossignol JF, Abu-Zakry M, Hussein A, Santoro MG. Effect of nitazoxanide for treatment of severe rotavirus diarrhoea: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:124-129.

Rouhani S, Meloney L, Ahn R, et al. Alternative rehydration methods: a systematic review and lessons for resource-limited care. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e748-e757.

Santos M, Maraon R, Miguez C, et al. Use of racecadotril as outpatient treatment for acute gastroenteritis: a prospective, randomized, parallel study. J Pediatr. 2009;155:62-67.

Shavit I, Brant R, Nijsen-Jordan C, et al. A novel imaging technique to measure capillary-refill time: improving diagnostic accuracy for dehydration in young children with gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2402-2408.

Sotir MJ, Ewald G, Kimura AC, et al. Outbreak of Salmonella Wandsworth and Typhimurium infections in infants and toddlers traced to a commercial vegetable-coated snack food. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:1041-1046.

Spandorfer PR, Alessandrini EA, Joffe MD, et al. Oral versus intravenous rehydration of moderately dehydrated children: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005;115:295-301.

Stachan NJC, Forbes KJ. The growing UK epidemic of human campylobacteriosis. Lancet. 2010;376:665-666.

Turck D, Bernet JP, Marx J, et al. Incidence and risk factors of oral antibiotic–associated diarrhea in an outpatient pediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:22-26.

UNICEF and World Health Organization. Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. New York: UNICEF; 2009.

Walker CF, Bhutta ZA, Bhandari N, et al. Zinc during and in convalescence from diarrhea has no demonstrable effect on subsequent morbidity and anthropometric status among infants <6 mo of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:887-894.

Wardlaw T, Salama P, Brocklehurst C, et al. Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. Lancet. 2010;375:870-871.

Widdowson MA, Cramer EH, Hadley L, et al. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis on cruise ships and on land: Identification of a predominant circulating strain of norovirus—United States, 2002. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:27-36.

332.1 Traveler’s Diarrhea

Traveler’s diarrhea is a common complication of visitors to developing countries and is caused by a variety of pathogens, in part depending on the season and the region visited (Table 332-12). Traveler’s diarrhea has a high attack rate among travelers from higher-income countries visiting, during the summer, countries in a warmer climate that have a high prevalence of indigenous infectious diarrhea. Traveler’s diarrhea can manifest with watery diarrhea or as dysentery.

Treatment

Antibiotics, with or without loperamide, can also reduce the number of unformed stools. Short-duration (3 days) therapy with fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, or rifaximin is effective; the choice of antibiotic depends on the age of the patient, the potential organism, and the organism’s local resistance patterns. For up-to-date information on local pathogens and resistant patterns, see www.cdc.gov/travel.

Gascón J. Epidemiology, etiology and pathophysiology of traveler’s diarrhea. Digestion. 2006;73(Suppl 1):102-108.

Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ. 2008;337:863-867.

Leung AK, Robson WL, Davies HD. Traveler’s diarrhea. Adv Ther. 2006;23:519-527.

Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in traveler’s diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1007-1014.