Chapter 7 Acute coronary syndromes

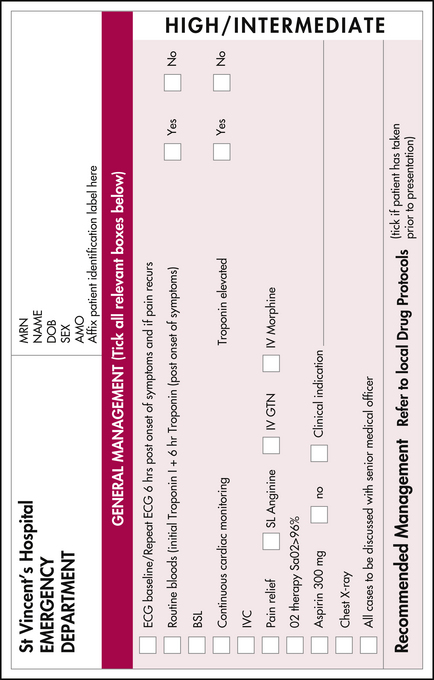

Symptoms and signs which may indicate an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) need to be identified as soon as possible, ideally by the patient, so that treatment can be initiated to avoid or minimise myocardial damage and to avert the risk of life-threatening complications. A defibrillator must be immediately available with staff trained in its use. Assign a high priority at triage to patients with a history of chest pain, breathlessness, syncope or palpitations. Provide ECG monitoring and supplemental oxygen and insert an intravenous cannula as soon as possible. Send blood samples for testing and provide analgesia (nitrates and/or morphine) and, unless contraindicated, give oral aspirin (300 mg).

ASSESSMENT

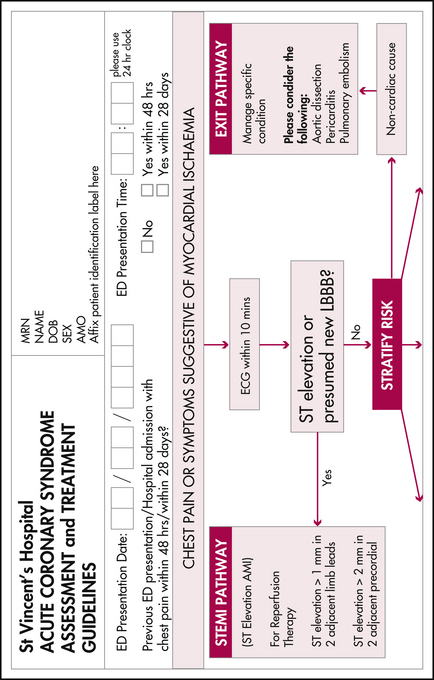

In some cases no ACS can be demonstrated and an alternative diagnosis is established, such as aortic dissection, pericarditis or pulmonary embolism

| STEACS | NSTEACS |

|---|---|

| ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome usually referred to as STEMI (ST–segment elevation myocardial injury) |

or a non-cardiovascular cause such as pneumonia, musculoskeletal pain or gastro-oesophageal disease may be identified. In a significant subgroup of presentations, immediately serious illness can be excluded and, although no diagnosis is reached, the patient can be discharged for follow-up outpatient assessment.

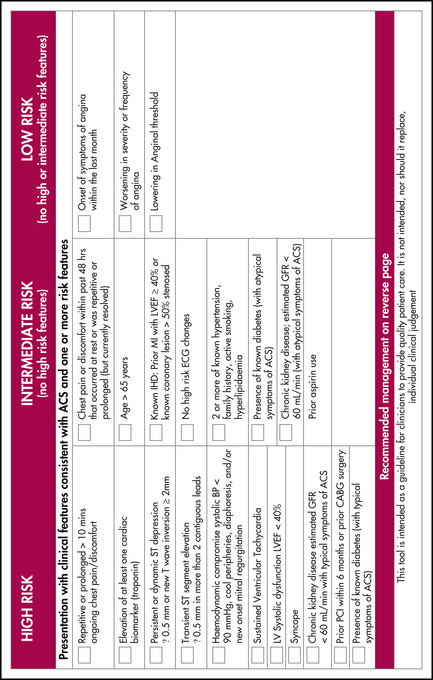

DIAGNOSING AND STRATIFYING ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

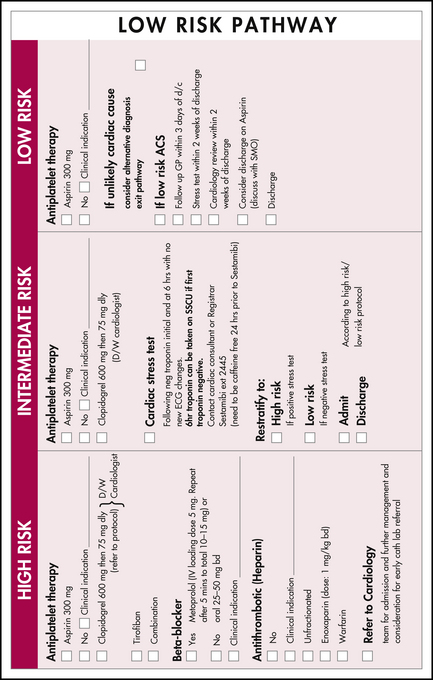

History, examination, investigation and management proceed rapidly and concurrently and senior staff should be contacted as soon as possible (see Figure 7.1).

Tests to include are listed in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Tests to aid in the diagnosis and stratification of patients with ACS∗

| Test | Comment |

|---|---|

| Full blood count | Anaemia or polycythaemia may need treatment, baseline platelet count (particularly if heparin is to be used) |

| Coagulation PT and APTT | Guides anticoagulant therapy |

| Serum chemistry |

APTT, activated partial thrombin time; CXR, chest X-ray; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NIDDM, non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; PT, prothrombin time

∗ Additional tests such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) and B-type natriuretic protein (BNP) or Pro-BNP are still being evaluated. In some settings bedside cardiac echocardiography can be valuable as it may be able to provide information on wall motion (myocardial ischaemia or infarction), ejection fraction (heart failure, systolic or diastolic dysfunction), valvular disease (aortic stenosis, acute mitral valve chordae disruption), free wall rupture, aortic or pericardial disease. Drug screening (cocaine, amphetamines) may be relevant. An alternative diagnosis of pulmonary embolism can sometimes be made when significant right heart abnormality is seen on echo.

∗∗ Elevated or rising troponin T and I measurements indicate myocardial damage and are predictors of increased risk of cardiac mortality. It may take several hours for troponin levels to rise and a series of tests may be required with an initial measurement at presentation and subsequent testing at 6 or more hours from the time of onset of the pain. Troponin may sometimes also be elevated in patients with heart failure, tachycardia, myocarditis, pericarditis or other non-ischaemic cardiac injury.

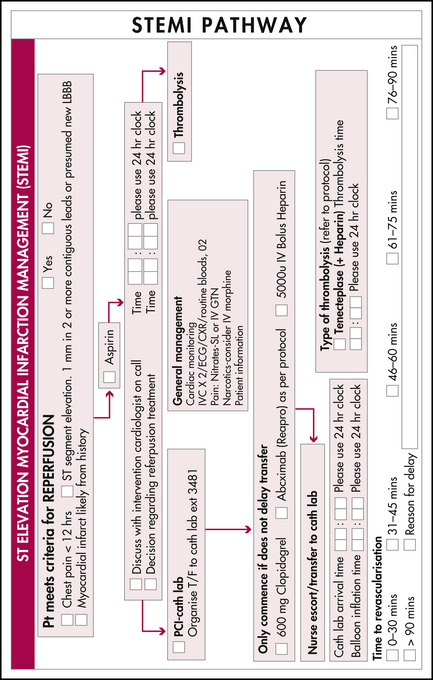

MANAGEMENT OF ACS WITH DIAGNOSTIC ECG CHANGES (STEMI)

Time-critical reperfusion therapy

Time-critical reperfusion therapy should be immediately considered when diagnostic ECG changes are present and the patient has presented within 12 hours of symptom onset. Logistics and local protocols will strongly influence the decision between percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and fibrinolysis, unless contraindications are present.

Adjunctive reperfusion therapy

Additional treatment

Although only a minority of patients (less than 6%) with chest pain associated with cocaine use will have proven cardiac myonecrosis, cocaine (a vasoconstrictor) has multiple effects that can contribute to the development of myocardial ischaemia hours or days after ingestion. Even small doses have been associated with vasoconstriction of coronary arteries, which may be more accentuated in patients with preexisting coronary artery disease. Cocaine users have been shown to have accelerated atherosclerosis as well as elevated levels of C-reactive protein, von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen. Anterior and inferior infarctions are equally likely and most are non-Q wave. Initial typical ischaemic ECG changes are relatively uncommon. In general, beta-blockers should be avoided; benzodiazepines are often used. Mortality overall is relatively low.

| Therapy | Dose | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen | 6 L (non-rebreather) | Issues (uncommon) with patients retaining CO2 |

| Aspirin | 300 mg PO (soluble or rapidly absorbable) | True allergy or bleeding risks may contraindicate |

| Nitrates | SL or spray or titrated IV | Headache, flushing, hypotension may occur with higher doses |

| Morphine | 2.5–5.0 mg IV increments | Nausea, decreased LOC and ventilation, hypotension |

| Metoprolol | 2.5–5.0 mg IV increments | Asthma, bradycardia, heart block, other side effects and contraindications |

| Clopidogrel | 600 mg PO loading | Increased bleeding risk |

| Heparin | Low-MW or unfractionated protocols | Bleeding risk, HITS |

| Tenectoplase | Dose per kg, max 10,000 U | Bolus |

| Abciximab | IV protocol | Not with fibrinolytics (or at least reduce dose) |

| Frusemide | 40–80 mg IV | Higher doses needed if renal impairment present |

HITS, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia syndrome; LOC, level of consciousness; MW, molecular weight

MANAGEMENT OF ACS WITHOUT DIAGNOSTIC ECG CHANGES (NSTEACS)

ADDITIONAL MANAGEMENT

Provide patients with support and advice to address the risk factors at a suitable time. A chest pain management plan is often appropriate. For all patients and their families, consider the level of social support and provide assistance for those at risk through referral to cardiac, rehabilitation and other services (e.g. social work, drug and alcohol misuse clinic). Consider patient support groups.

Aroney C.N., Aylward P., Kelly A.-M., et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia/Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2006. Med J Aust. 2006;184:S1-S32.

McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE et al. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188950. Online. Circulation Mar 17, 2008.

Gershlick A.H., Stephens-Lloyd A., Hughes S., et al. Rescue angioplasty after failed thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2758-2768.

Kastrati A., Mehilli J., Neumann F.J., et al. Abciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR-REACT 2 randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1531-1538.

Aroney C.N., Aylward P., Chew D.P., et al. 2007 Addendum to the National Heart Foundation of Australia/Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes 2006. Med J Aust. 2008;188(5):302-303.

Nallamothu B.K., Bates E.R. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: is timing (almost) everything? Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:824-826.

Madsen J.K., Grande P., Saunamaki K., et al. Danish multicenter randomized study of invasive versus conservative treatment in patients with inducible ischemia after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction (DANAMI). DANish trial in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 1997;96:748-755.