Chapter 24 Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction

Introduction

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO) is a disorder characterized by massive dilation of the colon in the absence of mechanical obstruction. This severe motility disturbance, also known as Ogilvie’s syndrome,1 usually develops in hospitalized patients and is associated with various medical and surgical conditions. The tension on the colon wall resulting from the extreme dilation can lead to ischemic necrosis and perforation, especially in the cecum. The rate of spontaneous perforation has been reported to be 3% to 15% with an attendant 40% to 50% mortality rate.2–5 Despite the potential risk of perforation, approximately 75% of patients with ACPO recover over an average of 3 to 5 days when treated with a variety of conservative measures.3,4 During the sometimes prolonged recovery phase, however, ACPO contributes greatly to patients’ discomfort and immobilization and may delay institution of enteral nutrition.

For the minority (about 25%) of patients who fail to respond to conservative therapy and for patients who have severe, prolonged colonic dilation risking perforation, more active interventions are instituted. In the past, surgical cecostomy and hemicolectomy were the main options in severe or refractory cases. Subsequently, colonoscopy and various radiologic procedures were reported to help decompress the colon.5–10 More recently, medications such as neostigmine have been shown to be effective.11 The timing and combination of conservative and more active interventions must be individualized according to the severity of ACPO and the patient’s comorbidities.

Epidemiology

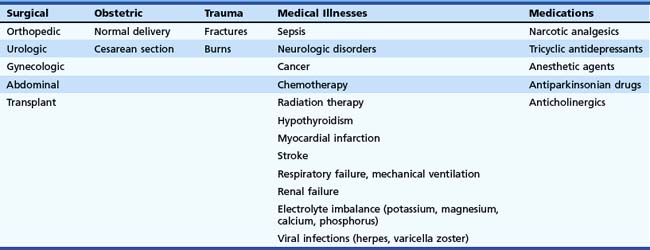

ACPO is relatively uncommon. It can be triggered by various acute medical and surgical illnesses. Typically, rapid-onset abdominal distension begins within a few days of the onset of the underlying illness.2 Because ACPO is uncommon, one must look at reviews that examine several years of reported cases to be able to draw conclusions about the epidemiology of the condition. Numerous case reports and reviews describe specific triggers. However, each proposed underlying condition seems to be associated with the development of ACPO in only a very small percentage of cases. ACPO has been reported after various surgeries, including orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, neurologic, and organ transplants.3,4,12–21,22 It is seen in obstetrics after vaginal deliveries and cesarean sections.3,23,24 Trauma and burn patients sometimes develop ACPO.3,4,12,25 Various medical illnesses are known to cause ACPO, including sepsis, respiratory failure, mechanical ventilation, renal failure, myocardial infarction, vascular emergencies, sickle cell crisis, and cancer.3,4,12,26–37 Many medications can precipitate ACPO, especially narcotic analgesics and any medication that decreases peristalsis, such as tricyclic antidepressants or anticholinergic drugs.5,7,38–40 Table 24.1 lists these associated conditions. Although the connection between any of these causes and ACPO is most likely through a disturbance in the autonomic innervation of the bowel, other variables, such as patient age; comorbidities; and factors such as immobility, medications, and electrolyte imbalances, are thought to help precipitate the onset in an individual patient.2

In one review of 351 ACPO cases from 1948–1980, 88% followed surgery, trauma, or acute medical illnesses.3 The remaining 12% were classified as idiopathic. This review reported a 15% perforation rate, with a 45% mortality in patients with colonic perforation. This high mortality was attributed in part to the fact that these patients already had serious underlying medical or surgical problems.

In another review of 400 patients from 1970–1985, 95% of the cases had identifiable underlying medical, surgical, or obstetric conditions4; this left only 5% to be categorized as idiopathic. ACPO usually developed within 5 days of onset of the underlying condition. The median patient age was about 60 years, and the male-to-female ratio was 1.5:1. Perforation rate was 20%, and mortality in patients with perforation was about 40%. Overall, mortality in the group was 15%. Mortality rate was affected by age, cecal diameter, length of dilation of colon, presence of ischemia in bowel wall, and patient comorbidities. One important observation in this review was that patients with cecal diameter 8 to 25 cm usually had viable colon without significant ischemia. Cecal size alone is not the only factor in the risk of perforation. Other variables, such as the acuity of the onset and the duration of distention, were also potentially important factors.

Pathogenesis

In 1948, Ogilvie1 first described massive colonic distention in two patients who had the onset of abdominal distention over a few weeks, rather than the more acute presentation that we currently refer to as Ogilvie’s syndrome. Ironically, by today’s criteria, neither would be categorized as ACPO. Both patients were ultimately found to have widespread intraabdominal malignancy with retroperitoneal involvement of nerve plexuses, leading Ogilvie to speculate that disruption of the autonomic innervation of the colon was the underlying cause of the disorder.1

Despite the variety of possible triggers of ACPO, the presentation is remarkably consistent. Generally, patients develop severe abdominal distention within 5 days of the onset of the medical or surgical insult. The intestinal dilation is usually most pronounced in the colon, especially proximal to the splenic flexure. On x-ray examination, the appearance is very similar to that of a patient who actually has an obstruction near the upper left colon, leading to the term pseudo-obstruction. These facts led to the hypothesis that the final common pathway of the development of the disease is an acute cessation of effective colonic motility resulting from a disruption of the autonomic supply of the left side of the colon. One hypothesis was that excess sympathetic stimulation of the colon was inhibiting contraction. This hypothesis seemed to be supported by the observation that this distention occurred in any sort of severe physical stress. In addition, epidural anesthesia to decrease sympathetic output has been reported to be beneficial treatment for ACPO.41 However, when guanethidine was used to block sympathetic tone, there was very little effect on colonic function in ACPO patients.42

The leading current theory about the pathogenesis of ACPO is that a decrease in parasympathetic stimulus to the colon is more important than an excess of sympathetic input.43 In the study of guanethidine mentioned previously, patients first were given guanethidine and then were treated with neostigmine to block acetylcholinesterase. Patients had a prompt return of colonic contraction only after the neostigmine, leading to the idea that a loss of parasympathetic tone is important in the development of ACPO. Some authors speculate that the parasympathetic deficiency is most pronounced in the left colon because of disruption of supply from the sacral plexus; this may explain why the left colon is contracted and aperistaltic in ACPO. Since these pioneering studies, the one medical treatment that has had the most consistent success in treatment of ACPO has been the use of neostigmine to cause a sudden increase in acetylcholine concentration at parasympathetic nerve synapses and an increase in colon peristalsis.

Other factors that likely contribute to the pathogenesis of ACPO are chronic underlying bowel motility disorders and constipation, patient immobility, electrolyte imbalance, medications such as narcotics, and mechanical ventilation. These other factors may contribute to the autonomic imbalance, directly suppress muscular function of the colon, or simply increase the amount of gas that is entering the digestive tract. At least 50% of patients with ACPO have significant electrolyte abnormalities, especially low potassium, magnesium, and calcium.4 Secretory diarrhea (with high potassium and low sodium concentration in the stool) can occur in ACPO. This is thought to be due to the effect of autonomic nervous system disturbance and of colonic distension on the activity of the apical (BK) potassium channels in the colonic mucosa.44

Usually the perforation risk is not very high in patients with cecal diameter less than 12 cm. Paradoxically, studies have shown that patients with ACPO and cecal diameter greater than 25 cm can recover without incident. Other variables, such as elasticity of the muscle wall, adequacy of blood supply, and time course of distention must be important as well in determining whether the colon remains viable. Some studies indicate an association between the duration of ACPO and perforation risk and indicate that patients with persistence of distention for more than 5 days have higher perforation rates.45

Clinical Features

ACPO is seen mainly in patients who are hospitalized for an acute medical, surgical, obstetric, or traumatic event. The condition progresses at a variable rate, usually over 2 to 7 days. The nearly universal symptom is progressive abdominal distention. The reported frequency of other symptoms is quite varied. Abdominal pain (10% to 80%), nausea (10% to 60%), vomiting (10% to 60%), diarrhea (30% to 40%), constipation (40% to 50%), and respiratory compromise resulting from distention all have been reported.3–57 Patients with ischemia and perforation are much more likely to have abdominal pain and fever.

Laboratory abnormalities include an elevated white blood cell count in up to 25% of patients without perforation and in almost 100% of patients with perforation.4 Abnormalities in electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus and abnormalities in thyroid function are not caused by ACPO but are thought to contribute to colonic dysfunction. These laboratory values should be checked and corrected, if abnormal.

Abdominal x-ray films show colonic distention, usually most pronounced in the cecum, ascending, and transverse colon. In contrast to patients with severe obstipation, the colon is distended primarily with gas, not stool. There is often an apparent “cutoff” near the splenic flexure with a collapsed left colon. The location of the cutoff varies. In one review, the cutoff was at the splenic flexure in 56% of patients, at the hepatic flexure in 18%, and at the descending or sigmoid colon in 27%. Although the small bowel is said usually to have less dilation in ACPO, one report indicated 80% of patients had some small bowel dilation. Air-fluid levels have been reported in 40%. X-ray evidence of gas in the bowel wall or free intraperitoneal air is indicative of colonic perforation. Radiographic water-soluble contrast enemas are often needed to rule out a true mechanical obstruction. As discussed in the treatment section, the use of water-soluble contrast material has been reported to have a therapeutic effect in some patients.46

Differential Diagnosis

Toxic megacolon resulting from infections such as Clostridium difficile should be considered in patients who have been exposed to antibiotics or prolonged care in a hospital or nursing facility, where they may have contracted the infection. Generally, such patients had severe diarrhea before the onset of the abdominal distention. Other colonic infections leading to toxic megacolon have been reported, particularly in immunosuppressed patients. In some cases, these patients seem to have a presentation indistinguishable from classic ACPO. However, when the colonic distention is due to infection, patients usually have an elevated white blood cell count; thickening of bowel wall on x-ray films; and endoscopic evidence of severe colonic erythema, edema, ulceration, or pseudomembranes on flexible sigmoidoscopy. Stool studies for enteric pathogens and C. difficile toxin are important in this setting.47

Similarly, toxic megacolon resulting from IBD can usually be differentiated from ACPO by a review of clinical history, laboratory results, x-ray films, and findings on sigmoidoscopy.48 Patients with IBD should have had a history of diarrhea (often bloody) and abdominal cramps before the development of colonic distention. Blood test results usually show leukocytosis. Abdominal x-ray films often show bowel wall edema. Sigmoidoscopy should show changes consistent with IBD. Lastly, the presence of chronic pseudo-obstruction can often be excluded by a careful review of the patient’s history, old records, and prior abdominal radiographs when available.

Treatment

Because ACPO is uncommon, there have been few controlled trials of the treatments that are currently considered the standard of care. Most data are from reviews, observational studies, and case presentations. Therapy is generally divided into conservative measures and active interventions. Because at least 75% of patients with ACPO experience resolution with a combination of conservative measures, these are generally tried first for at least 24 to 48 hours in most patients before more active interventions are considered.49 The reported success from these measures ranges from 33% to 100%.25–27

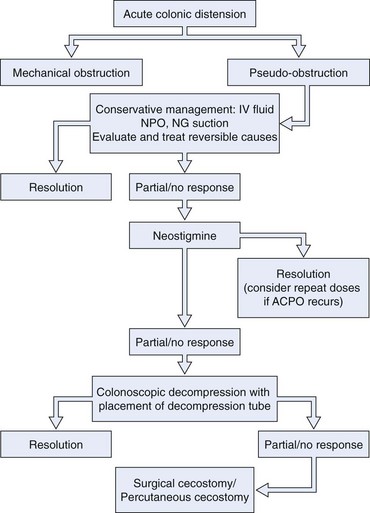

The following sections describe conservative therapy, medication therapy, colonoscopy, and surgical approaches for ACPO. These treatments are often combined. Conservative measures are typically continued when more active interventions are added. The order and combination of these measures must be individualized to a patient’s clinical presentation and course. There have been a number of excellent recent reviews on the topic of treatment of ACPO.50–56 Fig. 24.1 outlines a proposed treatment algorithm for most patients with ACPO, modified from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy practice guideline on treatment of this condition.49

Conservative Therapy

Conservative measures for treatment of ACPO include most, if not all, of the following, depending on individual circumstances.38 The patient is made nil per os (NPO), and nasogastric suction is used to prevent more gas from entering the gastrointestinal tract. Patients are mobilized as much as possible. If the patient is bed-bound, the patient’s position should be changed often from side to side and, when possible, into the prone and knee-to-chest position. A search for contributing factors should be done with correction of as many as possible. One should withdraw medications that interfere with colonic motility, such as narcotic analgesics, anticholinergics, and calcium channel blockers. Electrolyte imbalance (especially potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus) should be corrected. Regular rectal examinations every 6 hours have been advocated as a way to encourage passage of colonic gas. Placement of a rectal tube is more often used for this purpose. Gentle tap water enemas are controversial but are advocated by some authors as a way to liquefy remaining stool. A water-soluble contrast enema, which can liquefy stool, is commonly performed to exclude mechanical obstruction. Some authors have reported a stimulant effect on motility that sometimes speeds recovery.46 Prophylactic antibiotics have not been studied and are not common practice. If a patient has a fever or elevated white blood cell count, broad-spectrum antibiotics can be considered while a careful evaluation is under way for signs of colonic ischemia, perforation, or other infections.

Conservative measures are continued for 24 to 48 hours before more active intervention is initiated. This recommendation is not based on controlled data but rather on the observation that patients whose severe colon dilation (>12 cm) persists for 4 to 5 days have a higher risk of ischemia and perforation.4

Although conservative therapy is generally successful, return of colon function in responders takes an average of 5 days. During this time, patients are contending with the consequences of ACPO, including distention, pain, delay in institution of enteral nutrition, compromised respiratory status, and delay in ambulation that can lead to other morbidities such as thromboembolism, atelectasis, and pneumonia These facts have led to a search for a safe and effective treatment not only for patients who are refractory to conservative measures but also to provide a more prompt resolution early in the course of the illness. Numerous active interventions have been reported to be useful for ACPO, including medications such as neostigmine,11 colonoscopy with or without placement of a decompression tube,57–63 meglumine diatrizoate (Gastrografin) enema,46 radiologic procedures such as placement of a transanal decompression tube,10 cecostomy, and surgical resection of part of the colon.

Medical Therapy

In the 1960s, Neely and Catchpole64 studied the effects of guanethidine (a sympathetic antagonist) and neostigmine (Prostigmine) (a cholinergic drug) on small bowel motility and found that these medications seemed to restore peristalsis. In 1992, Hutchinson and Griffiths42 treated 11 ACPO patients first with guanethidine and then with neostigmine. They found that 8 of 11 patients had prompt return of bowel motility but only after the neostigmine infusion. In 1995, Stephenson and coworkers16 presented results of a study showing that 11 of 12 ACPO patients treated with 2.5 mg of intravenous neostigmine had prompt resolution of their condition. These observations were confirmed by subsequent studies, including prompt clinical resolution in 75% of ACPO cases as presented by Turefano-Fuentes and coworkers65 in 1997 and in 26 of 28 cases treated by Trevisani and colleagues,66 whose results were published in 2000. Physiologic studies on neostigmine indicate that its indirect effect on muscarinic receptors in the bowel wall, presumably through increased local acetylcholine concentrations, results in increased colonic tone and increased coordinated colonic propulsion.67

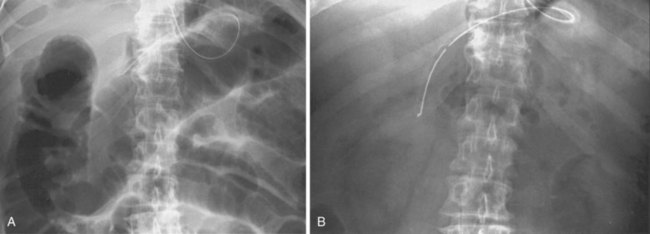

Because ACPO often resolves with conservative therapy alone, controlled trials of neostigmine and other therapies are important. The only controlled trial published to date was performed at the University of Washington11 and was published in 1999. The trial comprised 21 patients with ACPO (refractory to at least 24 hours of conservative measures and with a cecal diameter >10 cm) who were randomly assigned to receive either 2.0 mg of neostigmine or saline by a 3-minute intravenous infusion administered by a physician blinded to the treatment allocation. The responses recorded included immediate passage of flatus and stool; the amount of decrease in the measured abdominal girth; and the change in the diameters of the cecum, ascending, and transverse colon on abdominal x-ray films obtained 3 hours later (Fig. 24.2). Of the 11 patients randomly assigned to neostigmine, 10 had prompt resolution with substantial responses in all of the measured endpoints. The one nonresponder subsequently had a response when an open-label neostigmine dose was given 3 hours later. The median time to passage of flatus was 4 minutes (range 3 to 30 minutes). None of the patients given placebo responded, despite the continuation of conservative measures in all patients. Seven patients from the placebo group were treated with open-label neostigmine 3 hours later, and all had a prompt response. Since this publication, several uncontrolled studies have also reported similar results with usually about 80% to 90% of patients showing a prompt response to the drug. Sustained response after a single dose of neostigmine was similar in these other studies as well, usually about 60 to 70%.68–75 Some studies have shown success with repeated doses of the drug for patients with partial responses and recurrences.16

Studies have been done on factors that predict response to neostigmine. One retrospective review showed an 89% initial response and a 61% sustained response to a single dose of neostigmine. They found that narcotic medication use decreased not only the spontaneous resolution rate but also the response rate to neostigmine. Ambulatory patients had higher response rates as well. Interestingly, colon diameter and duration of ACPO before treatment did not influence response rate.71 Another study (prospective) enrolled 27 patients and found that electrolyte abnormalities and use of antimotility drugs were associated with poor response to neostigmine.72

Side effects of neostigmine include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, sweating, excess salivation, bronchospasm, and symptomatic bradycardia. Patients at risk for bradycardia, such as patients with preexisting bradyarrhythmias and patients receiving β blockers, are at potentially higher risk of complications from neostigmine, as are patients with severe bronchospasm. Some caution in patient selection is needed. Nonetheless, neostigmine can be used in most patients with ACPO when proper monitoring and precautions are in place. Patients should be kept supine on a pad or bed pan for the first 30 minutes after neostigmine and should be monitored by continuous electrocardiogram and frequent, intermittent blood pressure determinations. Transient bradycardia can occur but usually resolves quickly without treatment because of the short half-life of neostigmine. Atropine should be immediately available but should be given only if bradycardia is severe, prolonged, or associated with significant hypotension or persistent symptoms. Although neostigmine is partly cleared by plasma cholinesterase, about one-half of the clearance occurs in the kidneys; patients with renal failure have a prolonged half-life of neostigmine. In anephric patients, the elimination half-life is about 180 minutes compared with 80 minutes seen in patients with normal renal function.76

Glycopyrrolate, a selective anticholinergic agent, has been proposed as a way to decrease neostigmine side effects like bradycardia and bronchoconstriction. Since it has less effect on the bowel, glycopyrrolate might not interfere with the stimulatory effect of neostigmine in restoring colonic contraction. Although there has not been an organized study on this combined neostigmine/glycopyrrolate administration specifically in ACPO, one controlled study in spinal cord injury patients showed that the combination was as effective as neostigmine alone in prompting colon evacuation. Also, bradycardia and bronchoconstriction were not seen when the drugs were given together.77 Because it seems to be rapidly effective in most patients with ACPO and has a low side-effect profile compared with other active therapies such as colonoscopy or surgery, neostigmine appears early in the suggested treatment algorithm.47,78,79 Although mainly studied in adult patients, there have been case reports of successful use in pediatric patients as well.37,80 Most studies indicate that as long as conservative measures are continued, the recurrence rate of ACPO after neostigmine is low.11 Nonetheless, repeat doses can be tried in case of recurrence before one resorts to more invasive techniques. Because the elimination half-life is 80 minutes, retreatment is not advisable at intervals less than every 3 hours.

Since there is the issue of recurrence of colonic distension after neostigmine, as well as after colonoscopic decompression, efforts have been made to reduce recurrence. One controlled study showed that, after successful decompression with either neostigmine or colonoscopy (with decompression tube placement), the administration of polyethylene glycol solution twice daily (orally or per NG mixed with water) for 7 days reduced the recurrence rate for colonic distension (0/15 in PEG group versus 5/15 in placebo group).81

Although slower infusion of neostigmine has not been studied in ACPO, neostigmine drip over 24 hours at 0.4 to 0.8 mg per hour has been shown to be very effective in critically ill ICU patients with ileus. Eleven out of thirteen patients in the neostigmine group recovered bowel motility and passed stools while none of the eleven in the placebo group did. Interestingly, these authors did not observe neostigmine side effects of bradycardia or bronchospasm.82

Other medical therapies have been reported, including prokinetics such as metoclopramide,83 erythromycin,84,85 and cisapride.86 Most reports on these other agents have been anecdotes of one or two patients. The published reports on use of metoclopramide have been disappointing. Some reports have questioned the wisdom of applying a prokinetic such as metoclopramide out of concern that its main stimulus is on emptying the upper gut; this theoretically may deliver even more gas to the colon without adequate stimulus of the colon itself and worsen the distention there. Since the use of opioid medications has been associated with ACPO and also with failure to respond to conservative and neostigmine therapy, there may theoretically be some benefit to use of peripheral opioid receptor blockers like methylnaltrexone. However, the results of studies on the use of this and other peripheral opioid receptor antagonists like alvmivopan have been quite mixed.87–89

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is useful in treating ACPO in many ways. First, it is used to suction the extra gas and decompress the colon directly. Colonoscopy is also used rule out mechanical obstruction and to check for signs of colonic mucosal ischemia and necrosis. Lastly, it can be used to place a guidewire into the proximal colon over which a decompression tube can be placed. The reported rate of intubation proximal to the hepatic flexure in the setting of ACPO is at least 70%.5

Although there are no controlled trials proving its efficacy, colonoscopic decompression has been central in the therapy of ACPO patients who fail conservative measures. Its successful use was first reported in 1977 by Kukor and Dent.6 Since then, numerous uncontrolled studies have reported initial clinical success with colonoscopy in about 70% of cases.7,8,17,26 Nonetheless, a high recurrence rate of 40% may lead to repeated colonoscopy to maintain the response–sometimes two or more additional procedures.5,7,57,90 Several authors have reported a lower recurrence rate if a decompression tube is left in place, especially if it is proximal to the hepatic flexure.58–60 One institution compared the recurrence rate of colonoscopy with decompression tube placement with historical controls of colonoscopy alone and found recurrence rates of 0% versus 45%.61 Some authors have criticized uncontrolled studies on colonoscopic decompression because they have not had control groups of conservative therapy alone (which may have differed over time) and have a referral bias of studying only patients specifically referred for the purpose of colonoscopic decompression.5,62

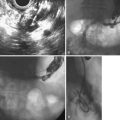

A summary of expert consensus on several aspects of therapeutic colonoscopy for ACPO follows.63 Colonoscopy in ACPO patients is technically difficult (performed in the unprepared colon of seriously ill patients) and carries an increased perforation risk of 1% to 3%.7,62 It should be performed only by expert endoscopists. Preparatory enemas are not needed because the stool remaining in the colon is usually already liquefied. In addition, enemas may increase the risk of perforation in patients with ACPO. Air insufflation must be kept to a minimum. Insufflation with carbon dioxide is preferable. As each new dilated segment is entered with the colonoscope, it should be decompressed. The mucosa should periodically be washed to examine for ischemic changes: duskiness to frank cyanosis, mucosal hemorrhage, and ulceration. Cecal intubation is desired. One should try to advance the colonoscope beyond the hepatic flexure. Fluoroscopy is useful to help determine the position of the colonoscope tip and should be used regularly.

Traditionally, it has been recommended that if mucosal ischemia is found, the colonoscope should be withdrawn, and the patient should be sent for urgent surgical resection, usually of the right colon, which is most often involved. More recently, successful treatment with conservative measures and tube decompression has been reported even in patients with endoscopic evidence of ischemia without necrosis (e.g., deep ulceration, exudate, black mucosa).91 Colonoscopic decompression can be attempted when the mucosal appearance noticeably improves promptly with decompression or if changes of erythema, mucosal hemorrhage, and scant shallow ulceration are present.

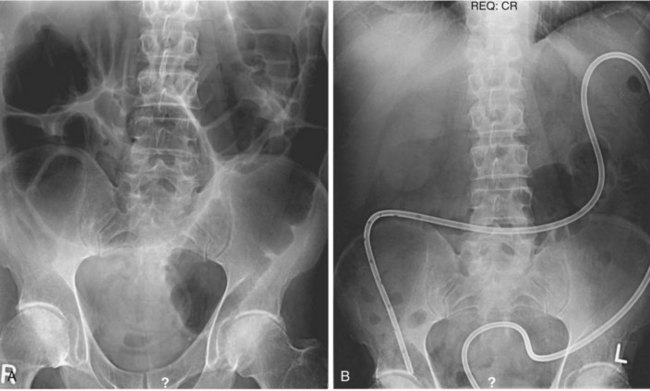

A tube for decompression should be placed at the initial colonoscopy. Various techniques have been described. The most popular and most effective to date is the placement of a guidewire through the colonoscope when the colonoscope tip is in the cecum or at least proximal to the hepatic flexure. The colonoscope is withdrawn over the wire, and the wire is used to guide a decompression tube into position. Fluoroscopy should be used to monitor the position of the colonoscope insertion tube, allowing straightening of the insertion tube during withdrawal and avoiding the problems of coiling of the tube and distal migration of the tip all the way back to the left colon during placement. A final position of the tube with the tip proximal to the splenic flexure can be satisfactory. Commercially available decompression kits use a 0.035-inch wire, an inner stiffening catheter, and outer drainage catheters that range from 7-Fr to 14-Fr in diameter. Other authors suggest using stiffer wires and larger tubes, such as a modified 18-Fr Levin or nasogastric tube. The tube is taped securely to the buttock, placed on low intermittent suction, and flushed with water (50 to 150 mL) at least every 6 hours to decrease clogging. Endoscopic approach to ACPO was reviewed by Saunders in 200753 and was also outlined in 2010 in the ASGE guideline.56 In the algorithm, a key point is that one starts with “acute colonic distention.” First, ischemia, perforation, and cecal volvulus need to be excluded. Then, mechanical obstruction (from tumor, benign stricture, sigmoid volvulus, etc.) is treated with endoscopic techniques or surgery, or at least ruled out with appropriate imaging. Finally, one starts down the part of the algorithm to treat ACPO only after all of these other possibilities are convincingly ruled out.

Daily abdominal x-ray films should be performed along with measurements of abdominal girth after colonoscopy and tube placement. The diameter of the colon in the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon should be tracked, and one should be vigilant for signs of free intraperitoneal air. Although there is sometimes a dramatic decrease in colonic dilatation immediately after decompression, more commonly the colonic dilatation decreases gradually (Fig. 24.3). One study showed that the mean change in cecal diameter 4 hours and 1 day after colonoscopic decompression was only about 2 cm.92 One should be patient, especially with a tube in good position and one that irrigates easily.

One report describes an alternative method for advancing a transanal decompression tube into the proximal colon using a steerable tricomponent coaxial catheter under fluoroscopic guidance.10 Successful placement proximal to the hepatic flexure and decompression was seen in four consecutive patients. Percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy93 can be performed in patients with refractory or recurring colonic distention. The technique is virtually identical to the placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Acute and delayed complications, including peritonitis, are reported to be an issue with percutaneous cecostomy.94

Surgery

For patients without peritoneal signs, tube cecostomy is advocated. For patients with peritoneal signs, a more extensive exploration is recommended with the surgical findings guiding the type of intervention.2 In patients with a viable cecum, a tube cecostomy can still be done. If there is significant ischemia or perforation, however, colonic resection is advised with the decision whether to do a primary anastomosis versus an ileostomy and mucous fistula depending on the patient’s condition and the degree of peritoneal contamination. Cecostomy has a high success rate in terms of decompression of the right colon.

In addition to the more traditional open surgical approach and placement of a Foley catheter or similar drain into the cecum, there are other variations of the technique. One is to perform laparoscopy first to check cecal viability and then to use the laparoscope to help place a cecostomy tube. T-fasteners are used to hold the cecal wall up against the abdominal wall.95 Some authors argue that with the availability and effectiveness of neostigmine and colonoscopy, surgery should be reserved for patients who have signs of perforation or peritonitis. Surgery for decompression in refractory cases should be infrequent.96

Other methods of placing cecal tubes have been reported.97 Radiologic methods have used fluoroscopy or computed tomography (CT) scan to guide placement of T-fasteners and drainage tubes into the cecum.9,98–100 Local operative complications and the morbidity of anesthesia and open abdominal surgery in patients who are generally already very ill make surgery a last resort for treatment of ACPO; this is especially true given the fact that conservative measures, medical therapies, and colonoscopy can successfully treat nearly all cases.

Future Trends

Medication therapies are likely to be the biggest area of future research in ACPO. Safer prokinetic agents could be applied earlier and more liberally. Many authors have speculated that neostigmine might be rendered easier and safer to use if patients were concomitantly treated with another agent to block some of the unwanted systemic cholinergic side effects, without lessening the therapeutic benefit of the neostigmine. Glycopyrrolate, an acetylcholine receptor antagonist, has been proposed for this purpose. Some physiologic measurements have shown that patients who were pretreated with glycopyrrolate still have a significant increase in colonic motility after neostigmine administration.101 Whether this combination would be as successful as neostigmine alone remains to be proven. The use of intravenous or oral medications to prevent recurrence is another potential area for future study. One hypothesis is that bowel-selective prokinetic agents might be used to decrease the high recurrence rate that is often seen in patients who have had successful initial decompressive therapy. If successful, such medicines could also be used in prophylaxis in high-risk situations, such as trauma patients. Lastly, although colonoscopy already has a high success rate, improvements in minimally invasive endoscopic techniques would be of further benefit.

1 Ogilvie H. Large-intestine colic due to sympathetic deprivation: A new clinical syndrome. BMJ. 1948;2:671-673.

2 Dorudi S, Berry AR, Kettlewell MG. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Br J Surg. 1992;79:99-103.

3 Nanni G, Garbini A, Luchetti P, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome (acute colonic pseudo-obstruction): Review of literature (October 1948 to March 1980) and report of four additional cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:157-166.

4 Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome): An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:203-210.

5 Jetmore AB, Timmcke AE, Gathright B, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome: Colonoscopic decompression and analysis of predisposing factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1135-1142.

6 Kukor JS, Dent TL. Colonoscopic decompression of massive nonobstructive cecal dilation. Arch Surg. 1997;112:512-517.

7 Geller A, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic decompression for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:144-150.

8 Bode WE, Beart RW, Spencer RJ, et al. Colonoscopic decompression for acute pseudoobstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome): Report of 22 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1984;147:243-245.

9 Crass JR, Simmons RL, Frick MP, et al. Percutaneous decompression of the colon using CT guidance in Ogilvie syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:475-476.

10 Bender GN, Do-Dai DD, Briggs LM. Colonic pseudo-obstruction: Decompression with a tricomponent coaxial system under fluoroscopic guidance. Radiology. 1993;188:395-398.

11 Ponec RJ, Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:137-141.

12 Spira IA, Rodrigues R, Wolff WI. Pseudo-obstruction of the colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1976;65:397-408.

13 Elmaraghy AW, Schemitsch EH, Burnstein MJ, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome after lower extremity arthroplasty. Can J Surg. 1999;42:133-137.

14 Clarke HD, Berry DJ, Larson DR, et al. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon as a postoperative complication of hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1642-1647.

15 Terhune D, Petrochko N, Jordan G, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome developing after ethanol ablation of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1985;133:838-839.

16 Stephenson BM, Morgan AR, Salaman JR, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome: A new approach to an old problem. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:424-427.

17 Love R, Starling JR, Sollinger HW, et al. Colonoscopic decompression for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) in transplant recipients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:426-429.

18 O’Malley KJ, Flechner SM, Kapoor A, et al. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) after renal transplantation. Am J Surg. 1999;177:492-496.

19 Koneru B, Selby R, O’Hair DP, et al. Nonobstructing colonic dilation and colonic perforations following renal transplantation. Arch Surg. 1990;125:610-613.

20 Cakir E, Baykal S, Haydar U, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome after cervical discectomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2001;103:232-233.

21 Caner H, Bavbek M, Albayrak A, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome as a rare complication of lumbar disc surgery. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27:77-78.

22 O’Malley K, Flechner S, Kapoor A, et al. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction after renal transplantation. Am J Surg. 1999;177:492-496.

23 Imai A, Mikamo H, Kawabata I, et al. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome) during pregnancy. J Med. 1990;21:331-336.

24 Shaxted EJ, Jukes R. Pseudo-obstruction of the bowel in pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;86:411-413.

25 Estela CM, Burd DA. Conservative management of acute pseudo-obstruction in a major burn. Burns. 1999;25:523-525.

26 Fausel CS, Goff JS. Nonoperative management of acute idiopathic colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). West J Med. 1985;143:50-54.

27 Sloyer AF, Panella VS, Demas BE, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome: Successful management without colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1391-1396.

28 Breccia M, Girmenia C, Mecarocci S, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome in acute myeloid leukemia: Pharmacological approach with neostigmine. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:614-616.

29 Schuffler MD, Baird HW, Fleming R, et al. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction as the presenting manifestation of small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:129-134.

30 Ikehara O. Vincristine-induced paralytic ileus: Role of fiberoptic colonoscopy and prostaglandin F2alpha. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:207-210.

31 Lopez MJ, Memula N, Doss LL, et al. Pseudo-obstruction of the colon during pelvic radiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:201-204.

32 Roman RJ, Loeb PM. Massive colonic dilation as initial presentation of mesenteric vein thrombosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:323-326.

33 Golden GT, Chandler JG. Colonic ileus and cecal perforation in patients requiring mechanical ventilatory support. Chest. 1975;68:661-664.

34 Caccese WJ, Bronzo RL, Wadler G, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome associated with herpes zoster infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:309-313.

35 Shrestha BM, Darby C, Fergusson C, et al. Cytomegalovirus causing acute colonic pseudo-obstruction in a renal transplant recipient. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:429-430.

36 Nomdedeu JF, Nomdedeu J, Martino R, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome from disseminated varicella-zoster infection and infracted celiac ganglia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:157-159.

37 Khosla A, Ponsky T. Acute colinic pseudoobstruction in a child with sickle cell disease treated with neostigmine. J Ped Surg. 2008;43:2281-2284.

38 Rex D. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Gastroenterologist. 1994;2:233-238.

39 Fahy BG. Pseudoobstruction of the colon: Early recognition and therapy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1996;8:133-136.

40 Ohri SK, Patel T, Desa L, et al. Drug-induced colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:346-350.

41 Lee JT, Taylor BM, Singleton BC. Epidural anesthesia for acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:686-691.

42 Hutchinson R, Griffiths C. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A pharmacologic approach. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:364-367.

43 Stephenson BM, Morgan AR, Drake N, et al. Parasympathomimetic decompression of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Lancet. 1993;342:1181-1182.

44 VanDinter T, Fuerst F, Richardson C, et al. Stimulated active potassium secretion in a patient with colonic pseudo-obstruction: a new mechanism of secretory diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1268-1273.

45 Johnson CD, Rice RP, Kelvin FM, et al. The radiologic evaluation of gross cecal distension: Emphasis on cecal ileus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:1211-1217.

46 Schermer CR, Hanosh JJ, Davis M, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome in the surgery patient: A new therapeutic modality. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:173-177.

47 Kyne L, Farrell R, Kelly C. Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:753-777.

48 Banerjee S, Peppercorn M. Inflammatory bowel disease: Medical therapy of specific clinical presentations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:185-202.

49 Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:789-792.

50 Saunders M, Kimmey M. Systematic review: acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:917-925.

51 Saunders M. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Best Practice & Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:671-678.

52 Saunders M, Kimmey M. Colonic pseudo-obstruction: the dilated colon in the ICU. Sem Gastroint Dis. 2003;14:20-27.

53 Saunders M. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin N Am. 2007;17:341-360.

54 DeGiorgio R, Knowles C. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Br J Surg. 2009;96:229-239.

55 DeGiorgio R, Stanghellini B, Tonini M, et al. Review article: the pharmacologic treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1717-1727.

56 Dominitz J, Baron T, Harrison M, et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of patients with know and suspected colonic obstruction and pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endoscopy. 2010;71:669-679.

57 Martin FM, Robinson AM, Thompson WR. Therapeutic colonoscopy in the treatment of colonic pseudo-obstruction. Am Surg. 1988;54:519-522.

58 Messmer JM, Wolper JC, Loewe CJ. Endoscopic-assisted tube placement for decompression of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Endoscopy. 1984;16:135-136.

59 Burke G, Shellito PC. Treatment of recurrent colonic pseudo-obstruction by placement of a fenestrated overtube. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:615-619.

60 Stephenson KR, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Decompression of the large intestine in Ogilvie’s syndrome by a colonoscopically placed long intestinal tube. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:116-117.

61 Harig JM, Fumo DE, Loo FD, et al. Treatment of acute nontoxic megacolon during colonoscopy: Tube placement versus simple decompression. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:23-27.

62 Vantrappen G. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Lancet. 1993;341:152-153.

63 Rex DK. Colonoscopy and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:499-508.

64 Neely J, Catchpole B. Ileus: The restoration of alimentary-tract motility by pharmacological means. Br J Surg. 1971;58:21-28.

65 Turegano-Fuentes F, Munoz-Jimenez F, Dell Valle-Hernandez E, et al. Early resolution of Ogilvie’s syndrome with intravenous neostigmine: A simple, effective treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1353-1357.

66 Trevisani GT, Hyman NH, Church JM. Neostigmine: Safe and effective treatment for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:599-603.

67 Law N, Bharucha AE, Undale AS, et al. Cholinergic stimulation enhances colonic motor activity, transit, and sensation in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1228-G1237.

68 Althausen PL, Gupta MC, Benson DR, et al. The use of neostigmine to treat postoperative ileus in orthopedic spinal patients. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:541-545.

69 Paran H, Silverberg D, Mayo A, et al. Treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction with neostigmine. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:315-318.

70 Abeyta BJ, Albrecht RM, Schermer CR. Retrospective study of neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Am Surgeon. 2001;67:265-269.

71 Loftus CG, Harewood MD, Baron TH. Assessment of predictors of response to neostigmine for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3118-3122.

72 Mehta R, John A, Nair P, et al. Factors predicting successful outcome following neostigmine therapy in acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: a prospective study. J Gastoenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:459-461.

73 Trevisani G, Hyman N, Church J. Neostigmine: safe and effective treatment for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:599-603.

74 Paran H, Silverberg D, Mayo A, et al. Treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction with neostigmine. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:315-318.

75 Abeyta B, Albrecht R, Schermer C. Retrospective study of neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Am Surgeon. 2001;67:265-269.

76 Cronnelly R, Stanski DR, Miller RD, et al. Renal function and the pharmacokinetics of neostigmine in anesthetized man. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:222-226.

77 Korsten M, Rosman A, Ng A, et al. Infusion of neostigmine-glycopyrrolate for bowel evacuation in persons with spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1560-1565.

78 Laine L. Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:192-193.

79 Amaro R. Neostigmine infusion: A new standard of care for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:304-305.

80 Gmora S, Poenaru D, Tsai E. Neostigmine for the treatment of pediatric acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. J Ped Surg. 2002;37:1-3.

81 Sgouros S, Vlachogiannakos J, Vassiliadis K, et al. Effect of polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution on patients with acute colonic pseudo obstruction after resolution of colonic dilation: a prospective, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:638-642.

82 van der Spoel J, Oudemans-van Straaten H, Stoutenbeek C, et al. Neostigmine resolves critical illness-related colonic ileus in intensive care patients with multiple organ failure—a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:822-827.

83 Tollesson PO, Cassuto J, Faxen A, et al. Lack of effect of metoclopramide on colonic motility after cholecystectomy. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:355-358.

84 Bonacini M, Smith OJ, Pritchard T. Erythromycin as therapy for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:475-487.

85 Armstrong DN, Ballantyne GH, Modlin IM. Erythromycin reflex ileus in Ogilvie’s syndrome. Lancet. 1991;337:378.

86 MacColl C, MacCannell KL, Baylis B, et al. Treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) with cisapride. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:773-776.

87 Wolff B, Michelassi F, Gerkin T, et al. Alvimopan, a novel, peripherally acting mu opioid antagonist: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placeo-controlled, phase III trial of major abdominal surgery and postoperative ileus. Ann Surg. 2004;240:728-735.

88 Delaney C, Wolff B, Viscusi E, et al. Alvimopan for postoperative ileus following bowel resection: a pooled analysis of phase III studies. Ann Surg. 2007;245:355-363.

89 Thomas T, Karver S, Cooney G, et al. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2332-2343.

90 Wegener M, Borsch G. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Surg Endosc. 1987;1:169-174.

91 Fiorito JJ, Schoen RE, Brandt LJ. Pseudo-obstruction associated with colonic ischemia: Successful management with colonoscopic decompression. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1472-1476.

92 Pham TN, Cosman BC, Chu P, et al. Radiographic changes after colonoscopic decompression for acute pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1586-1591.

93 Ramage J, Baron T. Percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:752-755.

94 Bertolini D, Saussure P, Chilcott M, et al. Severe delayed complication after percutaneous endoscopic coloscopy for chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastro. 2007;13:2255-2257.

95 Duh Q, Way LW. Diagnostic laparoscopy and laparoscopic cecostomy for colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:65-70.

96 Hutchinson R. Pharmacologic treatment of colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:781-782.

97 Ponsky JL, Aszodi A, Perse D. Percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy: A new approach to nonobstructive colonic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:108-111.

98 Chevallier P, Marcy P, Francois E, et al. Controlled transperitoneal percutaneous cecostomy as a therapeutic alternative to the endoscopic decompression for Ogilvie’s syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:471-474.

99 VanSonnenberg E, Varney RR, Casola G, et al. Percutaneous cecostomy for Ogilvie’s syndrome: Laboratory observations and clinical experience. Radiology. 1990;175:679-682.

100 Chevallier P, Pierre-Yves M, Francois E, et al. Controlled transperitoneal percutaneous cecostomy as a therapeutic alternative to the endoscopic decompression for Ogilvie’s syndrome. Am Coll of Gastroenterology. 2002;97:471-474.

101 Child CS. Prevention of neostigmine-induced colonic activity: A comparison of atropine and glycopyrronium. Anesthesia. 1984;39:1083-1085.

102 Nietsch H, Kimmey MB. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. In: Waye J, Rex DK, Williams CB, editors. Colonoscopy: Principles and Practice. London: Blackwell Science; 2004:596-602.