Acute Appendicitis

Perspective

Appendicitis is a common condition requiring emergency surgery. About 7% of people will develop appendicitis sometime during their lifetime. Most cases occur in adolescents and young adults, with the incidence in men being slightly higher than in women.1,2

Although the diagnosis is clinically clear in classic presentations, it still remains elusive in atypical presentations; after missed myocardial infarction and fractures, missed appendicitis represents the largest number of malpractice claims for practicing emergency physicians.3

Historical Perspective

The earliest evidence of appendicitis is suggested by the presence of right lower quadrant adhesions in an Egyptian mummy from the Byzantine era. In 1492, Leonardo da Vinci drew pictures of the colon and the appendix and called the structure an “orecchio,” which literally means ear. Claudius Amyand removed the first appendix incidentally in 1735 during the repair of a scrotal hernia in an 11-year-old boy. The appendix had perforated, and a cutaneous fecal-draining fistula had developed.4 The half-hour operation was done without anesthesia, and the boy fully recovered. In the early 1800s during the Lewis and Clark expedition, the only trip mortality was Charles Floyd, who was rumored to have died from a ruptured appendix.5

In 1880 in Europe, Lawson Tait performed the first successful planned appendectomy by removing a gangrenous appendix from a 17-year-old woman. Six years later Reginald Fitz, a pathologist, coined the term “appendicitis” when he read his classic paper at the first meeting of the Association of American Physicians. Fitz correctly described many of the pathophysiologic changes associated with appendicitis and advocated early surgery. Three years later, Charles McBurney described a point “determined by the pressure of one finger” between “one and a half and two inches from the anterior spinous process” which, when palpated, was associated with the greatest discomfort in patients with acute appendicitis (McBurney’s point). The general acceptance that appendicitis is a surgical disease did not occur until several decades later. Early surgical intervention became popular in the early 1900s around the time that King Edward VII perforated his appendix and was operated on days before his coronation.6

Principles of Disease: Pathophysiology

The appendix is a hollow, muscular, closed-ended tube arising from the posterior medial surface of the cecum, about 3 cm below the ileocecal valve. Its average length is approximately 10 cm, and its normal capacity is 0.1 to 0.3 mL. The role of the appendix in human physiology is unclear, but some recent studies on biofilms suggest that the appendix may act as a repository for commensal bacteria that inoculate the large bowel and protect it from pathogens.7 Innervation of the appendix is derived from sympathetic and vagus nerves from the superior mesenteric plexus. Afferent fibers that conduct visceral pain from the appendix accompany the sympathetic nerves and enter the spinal cord at the level of the 10th thoracic segment. This causes referred pain to the umbilical area.

The majority of patients develop appendicitis because of an acute obstruction of the appendiceal lumen. This is often from an appendicolith, but obstruction can also be caused by a calculi, a tumor, a parasite, or enlarged lymph nodes. Of historical note, one of the more common causes of acute appendicitis from foreign objects in the early 19th century was ingested lead shells buried in quail meat.8 A recent case study describes lumen obstruction from a swallowed tongue stud.9

After acute obstruction, intraluminal pressures rise and mucosal secretions are unable to drain. The resulting distention stimulates visceral afferent pathways and is perceived as a dull, poorly localized pain. Abdominal cramping may occur as a result of hyperperistalsis. Next, ulceration and ischemia develop as the intraluminal pressure exceeds the venous pressure, and bacteria and polymorphonuclear cells begin to invade the appendiceal wall. The appendix may appear grossly normal at this time with evidence of pathology apparent only on microscopic examination. With time, the appendix becomes swollen and begins to irritate surrounding structures, including the peritoneal wall. The pain then becomes more localized to the right lower quadrant. If swelling does not abate, hypoxia leads to necrosis and perforation through the appendiceal serosal layer. This can lead to abscess formation or diffuse peritonitis. The time required for the appendix to perforate is highly variable and controversial; some experts believe that unless a virulent organism or genetic predisposition exists, many cases will spontaneously resolve. In most cases, perforation occurs within 24 to 36 hours. Elders may be more prone to earlier perforation owing to anatomic changes in the appendix associated with aging, such as a narrowed appendiceal lumen, thinner mucosal lining, decreased lymphoid tissue, and atherosclerosis.10

No direct cause of obstruction is noted in approximately one third of cases; it is surmised that in these cases inflammation is caused by viral, bacterial, or parasitic infection with subsequent mucosal ulceration or lymphoid hyperplasia.2

Clinical Features

Appendicitis is classically described as starting with the vague onset of dull periumbilical pain and continuing with the development of anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. The pain then migrates to the right lower quadrant, and a low-grade fever may develop. In most instances the patient has not previously experienced similar pain.2 Unfortunately, the presentation may be highly variable. If the appendix is retrocecal or retroiliac, the pain may be blunted by the presence of overlying bowel. If the appendix is elongated, the pain may be referred to the flank, pelvis, or right upper quadrant. Other, less typical symptoms seen with appendicitis are increased urinary frequency and the desire to defecate.2

Physical Examination

The most common finding on physical examination is localized abdominal tenderness, usually in the right lower quadrant. Tenderness is often noted over McBurney’s point, an area approximately 2 cm from the anterior superior iliac spine on an imaginary line drawn from that anatomic landmark to the umbilicus. However, because only 35% of patients have the base of their appendix within 5 cm of this point, the pain of appendicitis can be localized in other areas of the abdomen.11

Other physical examination findings include guarding and rigidity. Guarding is usually voluntary, and the patient can often be persuaded to relax. Rigidity is involuntary and implies more significant underlying pathology.2 Both of these findings reflect the tensing of the abdominal wall musculature to protect the underlying bowel.

Rebound tenderness, indicative of peritoneal inflammation, is a late finding in patients with appendicitis and usually occurs only after the appendix is significantly inflamed or ruptured. Rebound tenderness can be elicited by gradually pressing over the area of tenderness for 5 to 10 seconds and then quickly withdrawing the hand to just above the skin level. A positive response occurs when the patient reports increased pain as the hand is removed. Patients with rebound tenderness are very uncomfortable with this maneuver, and it should not be repeated unnecessarily.11 Evidence of peritoneal irritation can also be elicited by abdominal wall percussion or by having the patient cough, resulting in pain referred to the right lower quadrant.

Isolated rectal tenderness may rarely be the only site of localized pain in patients with a low-lying or retrocecal appendix. In general, however, rectal tenderness has a very limited diagnostic value, especially if concurrent right lower quadrant pain and tenderness are present.12,13 Although a single rectal examination may provide other important information, such as the discovery of a rectal mass or occult blood, multiple examinations are not justified.

Although any of the aforementioned signs may be present in patients with acute appendicitis, a review of 10 studies that evaluated 13 signs and symptoms of adult appendicitis identified certain findings that have a high positive likelihood ratio of identifying patients with appendicitis. These were migration of pain from the periumbilical area to the right lower quadrant, right lower quadrant tenderness, and abdominal wall rigidity.2 Conversely, the presence of pain for more than 48 hours, a history of previous episodes of similar pain, the lack of migration and right lower quadrant pain, and the lack of worsening pain with movement or cough make appendicitis less likely.2,13 A similar review of children with appendicitis concluded that fever and rebound tenderness are the most common findings.14

Vital signs are often normal, particularly early in the course. A low-grade fever is present in 15% of all patients with appendicitis, and in 40% of patients if perforation has occurred.15

Special Considerations

Young children with acute appendicitis usually are diagnosed after perforation has occurred. This may be because many common childhood illnesses are associated with nausea, anorexia, and vomiting, and young children may have difficulty communicating their discomfort.16 Anatomically, children have a thinner appendiceal wall and a less developed omentum, which may predispose them to perforation and diffuse peritonitis.

Women

The diagnosis of acute appendicitis in women of childbearing age is especially challenging. Before the advent of imaging, as many as 45% of women with symptoms suggestive of appendicitis had a normal appendix at surgery, and as many as one third of women with true appendicitis were initially misdiagnosed. Gynecologic disease can easily masquerade as appendicitis owing to the proximity of the right ovary, the fallopian tube, and the uterus to the appendix.17,18 Findings that may be more suggestive of abdominal pain of gynecologic origin are included in Table 93-1. Of note, although cervical motion tenderness is more common in patients with pelvic inflammatory disease, up to a quarter of women with appendicitis may also exhibit it.19 Because obtaining an accurate diagnosis of appendicitis is especially challenging in women, ancillary imaging should strongly be considered.

Table 93-1

| More suggestive of appendicitis | Migration of pain and tenderness localized to the right lower quadrant, anorexia, normal or minimally abnormal pelvic examination findings (i.e., isolated right adnexal tenderness) |

| More suggestive of pelvic inflammatory disease | Several days of symptoms, history of pelvic inflammatory disease, hunger, diffuse lower abdominal pain, bilateral adnexal tenderness, cervical motion tenderness, vaginal discharge |

Pregnant Women

Pregnant women have an overall risk of developing appendicitis similar to the general population.20 Of the three trimesters, appendicitis appears to occur slightly more often in the second trimester for unknown reasons. The diagnosis of appendicitis during pregnancy can be difficult, as early symptoms of appendicitis such as nausea and vomiting occur frequently in a normal pregnancy. Laboratory values are even less helpful, as leukocytosis is common during pregnancy. The accuracy of the physical examination may also be compromised, as enlargement of the uterus may alter the location of the appendix to the right flank or right upper quadrant. However, one study of pregnant patients with appendicitis found that most women still had presenting symptoms of right lower quadrant pain and tenderness, even when it occurred late in pregnancy.21

Although maternal death from appendicitis is extremely rare, fetal abortion occurs in about 5 to 15% of simple appendicitis cases and up to 37% of complicated cases.22 Because the morbidity is high, extra caution should be taken with pregnant women with abdominal pain.

Elder Patients

Elders are three times more likely to have a perforated appendix at surgery compared with the general population. There appear to be multiple causes for this, including anatomic age-related changes of the appendix, delay in seeking medical care, atypical presentations, and minimally elevated laboratory values.9

Complications

The complication rate after the removal of a normal appendix or an acutely inflamed appendix is roughly 3% and increases approximately three to four times if perforation occurs.14 The most common complication is infection. Localized wound infection occurs in about 2 to 7%, and deep intra-abdominal abscess occurs in 0.8 to 2%, with the higher percentages representing cases in which perforation has occurred.23

Other complications include a prolonged ileus, small bowel obstruction, pneumonia, and urinary retention and infection. In young women, perforation may cause obstruction of the fallopian tubes, leading to infertility, though recent studies suggest this is not as prevalent as once believed.24,25 Pregnant patients with appendicitis have an increased risk of premature labor (15-45%) and fetal death.

The mortality of uncomplicated appendicitis in otherwise healthy individuals is less than 0.1% but increases to about 3 to 4% with perforation in patients with comorbidities or advanced age. Although reported perforation rates vary significantly from study to study, the overall average is 20 to 30%. This increases greatly at the extremes of age. Elders have perforation rates as high as 60%, and children younger than 3 years can have perforation rates as high as 80 to 90%.9,15

The identification of factors that may increase a patient’s risk for perforation is evolving. The traditional belief has been that the natural course of appendicitis is inflammation that, if surgery is delayed, ultimately progresses to necrosis and perforation. Many experts now feel that in most patients the natural course of appendicitis is spontaneous resolution without perforation.26 This view is supported by general autopsy reports from the presurgical era, in which up to one third of corpses had evidence of periappendiceal scarring, and by studies that report successful resolution of early appendicitis with nonoperative management.27 It is hypothesized that a subset of the population is genetically predisposed to perforation owing to an early aggressive and exaggerated inflammatory response.28 The evidence for this is the relatively consistent population perforation rate even with the advent of increased imaging and earlier diagnoses. Most cases of perforation occur before medical evaluation, and hospital delays in operative management rarely appear to increase perforation rates.29

Diagnostic Strategies

Leucocyte Count and C-Reactive Protein

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase reactant synthesized by hepatocytes in response to an acute injury or inflammation. It has a slower rate of rise than the WBC count and a shorter half-life. A meta-analysis suggests that the overall sensitivity of CRP is approximately 62% and specificity 66%, thereby limiting its usefulness as a stand-alone diagnostic tool in patients with appendicitis.30 Several studies, however, have examined the diagnostic utility of combining the CRP and WBC count. Although most patients with complicated (perforated) appendicitis will have elevations of either or both laboratory values, most authorities have concentrated on the negative predictive value of a normal WBC count and CRP in ruling out appendicitis. Two meta-analyses assessing use of the combined values in adults found that patients with a WBC count below 10,000/mm3 and a CRP below 6 to 12 mg/L were unlikely to have appendicitis (negative likelihood ratio of 0.09), whereas those with a WBC count above 10,000/mm3 and a CRP above 8 mg/L were likely to have appendicitis (positive likelihood ratio of 23.32).31,32 Unfortunately, this test combination appears less helpful in pediatric patients, with one study showing that 7% of patients with acute uncomplicated appendicitis have a normal WBC count and CRP.32

In infection, CRP doubles every 8 hours and peaks at 36 to 50 hours; there is therefore growing interest in tracking a repeat CRP in patients with examination findings equivocal for appendicitis. A recent pediatric study showed that children with appendicitis had a 6-hour CRP increase of at least 4.8 mg/L.33

Diagnostic Scores

Several scoring systems have been developed that assign numerical values to different aspects of the history, physical examination, and laboratory test results in patients with right lower quadrant pain in an attempt to assist risk stratification in clinical decision-making. The modified Alvarado score uses a 9-point scoring system as follows: migratory right lower quadrant pain, 1 point; anorexia, 1 point; nausea or vomiting, 1 point; temperature above 37.5° C, 1 point; right lower quadrant tenderness, 2 points; rebound tenderness, 1 point; and leukocytosis, 2 points. A score below 4 is considered low risk, 4 to 6 represents moderate risk, and more than 6 represents high risk. Unfortunately, these scoring systems have yielded inconsistent results when used by themselves to determine the need for operative intervention and were particularly inaccurate when applied to female patients and patients at the extremes of age.2,34 Recent renewed interest in these scales has occurred, however, to determine if they can be used to stratify a patient’s need for advanced imaging. Whereas a low modified Alvarado score (<4) does not reliably exclude acute appendicitis, high scores (>6) may identify patients who would benefit from surgical consultation without imaging studies.35,36

Imaging Studies

Plain radiographs are not useful in diagnosing appendicitis owing to very low sensitivity and specificity. They are not recommended in the evaluation of appendicitis unless there is a significant concern for bowel obstruction, free air, or pneumonia.37

Barium Enemas

Barium enemas have a sensitivity of about 80 to 90% for detection of appendicitis, and the diagnosis is essentially ruled out if the entire appendix is filled with contrast.35 Unfortunately, a normal appendiceal lumen is often not visualized with this technique. Barium enemas are most helpful when other colon pathology is high in the differential diagnosis.

Nuclear Medicine Scans

The use of nuclear imaging with tagged WBCs has been well studied as a diagnostic tool for acute appendicitis.36,38 The reported sensitivities of nuclear scans depend on the tag used and range from 88 to 98%. The overall usefulness of these scans is limited owing to poor specificity; any process causing inflammatory changes in the lower abdomen can lead to a false-positive scan.

Ultrasonography

Graded compression ultrasound (US) has been prospectively shown to improve the clinical accuracy of the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.39 The reported sensitivity and specificity of US for acute appendicitis in most studies are 75 to 90% and 85 to 95%, respectively.40 There have been some recent advances in US techniques. One group reports an astonishing 98% visualization rate (compared with the often cited 2-45%) with the addition of simple repositioning maneuvers.41 Similarly, small studies using contrast-enhanced Doppler or harmonic waves (which allow for better resolution) show promise of higher sensitivities with lower radiation exposure.42–44

Computed Tomography

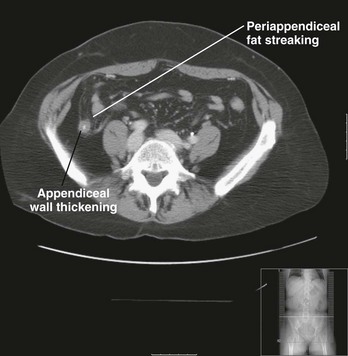

Abdominal pelvic CT scanning has been prospectively studied and shown to improve the clinical accuracy of the diagnosis of appendicitis.45,46 CT findings suggestive of appendicitis include an enlarged appendix (diameter greater than 6 mm), pericecal inflammation, the presence of an appendicolith (Fig. 93-1), or a periappendiceal phlegmon or abscess (Fig. 93-2). The sensitivity (87-100%) and specificity (89-98%) of CT scan varies by study and technique and by how authors categorize inconclusive scans in their statistical analyses. There are several different protocols used in scanning patients with right lower quadrant pain, including any one or a combination of oral contrast, rectal contrast, intravenous contrast, no contrast, low-dose radiation, and a 15-cm focused scan.

CT scanning has some advantages over US in the diagnostic evaluation of appendicitis. The appendix can usually be visualized, the technique is standardized, and alternative pathology often is identified. An added benefit is that the CT signs are relatively straightforward in most patients with appendicitis. This is an important consideration because the initial interpretation of the CT scan usually dictates patient disposition, and in academic teaching centers the scans may be interpreted by junior radiology residents after hours.47

The biggest disadvantages of CT scanning are the radiation exposure and the expense. The amount of radiation exposure on a routine full abdominal and pelvic CT study can vary dramatically depending on scanning parameters but is usually cited as being around 10 millisieverts (mSv), which is the same radiation dose as 500 chest radiographs. This amount is theoretically carcinogenic, and it has been proposed, based on World War II atomic bomb data, that the radiation from a single abdominal CT scan could cause a fatal cancer in 1 of every 2000 adults or 500 children scanned.48 One study estimates that of the 70 million patients who underwent CT scanning in 2007, over 27,000 patients (14,000 from abdominal pelvic CT) will ultimately develop a radiation-induced cancer.49

There are techniques that can be used to decrease radiation exposure in the evaluation of appendicitis. A limited focused scan through the right lower quadrant will decrease exposure but must be weighed against the possibility of missing an unusually placed appendix or alternative pathology. There have also been a few recent studies examining the use of low-dose CT scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis.50,51 Seo studied the utility of a noncontrast low-dose scan that uses a new software technology called sliding slab ray-sum to rule out appendicitis. The researchers estimated that a low-dose scan (approximately 4 mSv) would have a sensitivity of 95% for appendicitis and have a less than 10% required rescan rate.52 A small study in 2009 obtained similar results.53 Further research is needed to clarify several questions, such as the accuracy of the identification of a noninflamed appendix, the ability to distinguish between simple and complicated appendicitis, the sensitivity of diagnosing alternative pathology, and optimal scanning parameters.

Currently the most commonly used protocol to scan patients with right lower quadrant pain is with oral and intravenous contrast. Enteric contrast (either oral or rectal) is advocated by many radiologists because they feel it helps better delineate right lower quadrant anatomy by cecal contrast opacification. Oral contrast abdominal pelvic CT generally requires a 60- to 90-minute delay after contrast administration for distal small bowel opacification (though even then contrast may not be visualized in the cecum 20-30% of the time) and may be poorly tolerated in patients with nausea or an ileus. One study addressed poor oral transit time by adding polyethylene glycol to the oral contrast, which allowed good cecal opacification in 1 hour.49

Rectal contrast appears to be very sensitive for detecting acute appendicitis, with rates as high as 98%.54 It confers a number of theoretic advantages over oral contrast: It may be better tolerated in nauseated patients; there is no delay in scanning because of contrast transit time; and there is more consistent cecal opacification.55,56 These benefits must be weighed against patient and technician preference, as many find these scans invasive and messy.

Intravenous contrast is used at many institutions, as it will enhance an inflamed appendiceal wall and may aid in delineating alternative pathology. In one study, patients received oral contrast, followed by a focused 15-cm right lower quadrant scan, followed by a scan of the entire abdomen with intravenous contrast. CT sensitivities increased from 83 to 93% with the addition of the intravenous contrast scan.57

Several studies have given convincing arguments in favor of the use of an intravenous-contrasted scan without enteric contrast. Kharbanda looked at historical data comparing a protocol that included both rectal and IV contrast with a new IV contrast only protocol and found similar sensitivities (92 and 93%, respectively).58 Likewise, Kaiser reported sensitivities of 97% with intravenous contrast alone in children for appendicitis.59 The downside of intravenous contrast is the potential for adverse reactions, such as anaphylactoid reactions, skin extravasation, and renal injury, and its slightly increased cost.

Recently there has been increased interest in the use of CT scans that bypass the need for both enteric and intravenous contrast. The argument is that CT technology is advancing with multidetector helical scanners and that an enlarged inflamed appendix with surrounding periappendiceal fat streaking should be visualized on most noncontrast scans. These scans avoid the potential complications of enteric and intravenous contrast and decrease emergency department (ED) length of stay. A meta-analysis of seven studies showed an overall sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 96%, respectively, for the diagnosis of appendicitis with noncontrast scans.60 However, the study that contributed the most data to the analysis had a large number of patients with equivocal scans and a 23% rescan rate.61 It is not clear that such a high rescan rate is justifiable in lieu of the additional radiation exposure. At this time, the sensitivities for these noncontrast scans appear to be institution-specific. Several studies have found that noncontrast scans have sensitivities for appendicitis that range from 60 to 83%.62–65

The results of all these studies raise more questions than provide definitive answers regarding the ideal CT protocol to detect appendicitis. However, three salient points seem to consistently emerge. First, young or slender patients are less likely to have significant intra-abdominal fat, and the use of additional contrast (intravenous or enteric) may help delineate their anatomy. Second, intravenous contrast may be useful in identifying other causes of pain, which may be especially helpful in older patients with broader differential diagnoses. Third, the use of intravenous or oral contrast may be less important in establishing the diagnosis than the interpreting radiologist’s preference, experience, and access to clinical information. Hof showed that the difference in the inter-reader sensitivities of a noncontrast scan for appendicitis depends on the experience level of the radiologist, with sensitivities ranging from 81 to 95%.66 Kaiser compared real-time CT interpretations with blinded retrospective interpretations and found the latter to be associated with decreased sensitivities for appendicitis (90% vs. 97%).67 Keyzer found that perfect agreement regarding what was consistently identified as the appendix occurred only 71% of the time on noncontrast and intravenous scans interpreted by three different readers, and that scan reproducibility appeared to be more related to the presence of intra-abdominal fat and the skills of the individual radiologist than to the use of intravenous contrast.68

Finally, CT is not 100% accurate. Overall, approximately 5 to 10% of CT scans are considered inconclusive for appendicitis, and this number varies significantly among hospitals. Care should be taken not to label all inconclusive CT scans as “negative,” because up to 30% of these patients ultimately have histologic confirmation of appendicitis.62 The appendix is not visualized in 10 to 15% of inconclusive examinations. When this happens in patients with adequate cecal fat, secondary findings of appendicitis such as free fluid or fat stranding may suggest the diagnosis. Levine retrospectively reviewed 24 patients with histologically proven appendicitis who had “missed” CT scans and found 96% had a paucity of fat and 50% had a lack of cecal contrast opacification.63 When the appendix is not seen in an otherwise normal CT scan in a patient with adequate abdominal fat, the risk of acute appendicitis appears to be extremely low, with one study showing it to be less than 2%.64,65

These studies underscore the importance of sharing accurate clinical information with radiologists and considering their experience and comfort level when institutional scanning protocols are being developed. Because accuracy rates vary among radiologists, institutions should consider periodic review of their own experiences. The Washington state surgical study, the SCOAP Collaborative, showed that CT accuracy rates and negative appendectomy rates vary significantly across hospitals and recommended that local data be used in quality improvement and education interventions.69

In general, even patients with a true “negative” scan should be explicitly told to be reevaluated if their symptoms progress or do not resolve in the following 24 to 36 hours. This is particularly true in patients evaluated within the first few hours of symptoms, as early appendicitis may be missed on CT scan.70

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an emerging tool used in the evaluation of suspected appendicitis, with reported sensitivities similar to those of CT. Access to MRI is currently limited in most EDs, and its use is often confined to pregnant patients with an indeterminate US as an alternative to CT.70–74 As MRI becomes more available and concerns about nephrotoxicity from intravenous contrast and cancer-related deaths from ionizing radiation continue, MRI is likely to become increasingly popular and may eventually replace CT scanning in the evaluation of select patients with possible appendicitis.75

In-Hospital Observation

Despite the increased tendency to pursue diagnostic imaging in patients with right lower quadrant abdominal pain, studies suggest that most cases of appendicitis can be accurately diagnosed by performing serial physical examinations.76,77 A review of studies that have used active inpatient observation in patients with an equivocal diagnosis of appendicitis found a negative appendectomy rate of roughly 6% without an increase in perforation rates.59 Alternatives to inpatient observation that are used but have not been well studied include use of an ED observation unit and discharge with short-term follow-up for reevaluation.

Differential Diagnosis

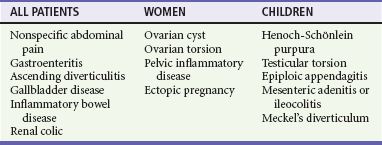

An elongated appendix can irritate almost any abdominal structure, so the differential diagnosis of appendicitis includes essentially any pathology that can cause abdominal pain. The more common diseases that can mimic appendicitis are listed in Table 93-2. Of note, the diagnosis of gastroenteritis should be made with caution and only in patients with vomiting and diarrhea.

Management

In recent years there has been renewed debate as to whether acute appendicitis is truly a surgical emergency. The traditional view that untreated early appendicitis inevitably progresses to a necrotic and perforated appendix has been questioned. As stated previously, some experts believe that patients with complicated appendicitis have either a genetic predisposition to an exaggerated inflammatory response or possible infection with a more virulent pathologic organism, leading to early aggressive disease.28 In general, this group of patients arrive for medical care with already-advanced disease. Along this reasoning, the remaining subset of patients usually have acute uncomplicated appendicitis and often will get better with medical management, including antibiotics and intravenous fluid alone. A meta-analysis of three studies that looked at nonoperative versus operative management of acute appendicitis showed that although the majority of patients recover without surgery, 42% require surgery, either during their initial hospitalization or during readmission.78 Currently, a nonsurgical approach is probably best reserved only for patients who are poor operative candidates.

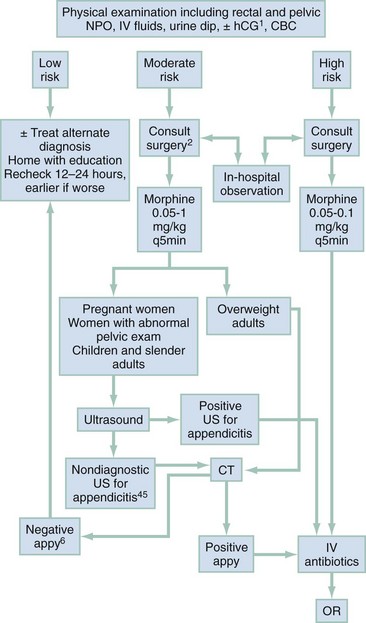

A strategy to manage patients with possible appendicitis is depicted in Figure 93-3. Patients should be kept on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status and undergo a complete physical examination, including a pelvic examination, with consideration of a rectal examination if there is concern for an atypically placed appendix or strong alternative diagnosis. Dehydrated patients should receive intravenous crystalloid fluids, and parenteral antiemetics should be given to patients who are nauseated or vomiting. All patients should be offered pain medicine. Multiple studies show that giving opiate pain medicine to adults or children with signs of appendicitis does not mask important physical findings or impair surgical decision-making.79,80 A recently published meta-analysis examining the relationship of opiate administration and changing abdominal findings concluded that, although the existing literature was not definitive, changes in physical signs appear to be minor and do not alter patient management.81 The practice of withholding analgesia from patients with abdominal pain pending surgical consultation is not supported by the medical literature. In rare instances in which local surgical preference or institutional policy requires this approach, delays in obtaining consultations should be minimized.

Controversy exists regarding when and how to best use advanced imaging techniques. Some authors have shown that CT scanning significantly decreases the rate of negative laparotomies, even in patients for whom the clinical suspicion of appendicitis is high.82–84 Others feel that diagnostic imaging is overused and has not improved patient care.85,86 Considering both these views, diagnostic imaging appears to be most helpful in a select group of patients, with the initial history, physical examination, and laboratory tests used to stratify patients by risk.

Equivocal-Risk Patients

Children with a suspicious presentation for appendicitis but who lack classic findings and have no clear alternative diagnosis may also be considered “equivocal.” US is usually considered the initial imaging study in children because it does not expose them to radiation. This should be a significant consideration, as children are particularly vulnerable to the risks of radiation owing to their increased cell division and their longer life expectancy.52,55

Researchers at Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford published their experience using a graded approach of US with selected follow-up CT for children with equivocal workups for appendicitis.87 They found that the US findings were definitively positive or negative in about 30% of patients. In patients with an equivocal US who went on to undergo CT, about 20% had appendicitis. It is interesting to note that only 52% of children with equivocal US findings went on to undergo CT. This was a retrospective study with limited follow-up, but the authors did not detect large missed appendicitis rates. Although they did not quantify the specific reasons that led to patient discharge without CT, their study opens the door for further research in this area. Improving physical examination findings after an equivocal US is reassuring, but this may be a circumstance in which repeating the CRP determination may be useful.35 If the US is nondiagnostic and the child’s clinical status has not improved, conservative management with a follow-up CT scan or admission for observation is encouraged.54

High-Risk Patients

Men and children with classic presentations of appendicitis are at high risk for appendicitis and receive little benefit from further imaging. Men with classic signs of appendicitis have the disease more than 90% of the time.89,90 A review of CT imaging for appendicitis at one institution showed that imaging dramatically decreased the number of negative appendectomies in women (from 43 to 7%) but had no significant effect in men.91 Another study showed that 65% of men were able to go to the operating room without a scan, with only a 4% negative appendectomy rate.92 Surgical consultation before imaging is therefore encouraged in these high-risk groups.

Once the decision to operate has been made, prophylactic antibiotics should be given to cover gram-negative and anaerobic organisms, as this has been proven to decrease both superficial and deep postoperative wound infections. Intravenous second-generation cephalosporins, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin, provide good coverage. If there is a high suspicion of perforation, the traditional treatment has been broad-spectrum triple antibiotics. However, new studies suggest that monotherapy with a second-generation cephalosporin or meropenem or piperacillin and tazobactam is effective with easier administration. Alternatively a once-a-day combination of ceftriaxone and metronidazole is also sufficient.93,94

The timing of surgical intervention has recently been challenged, with several studies suggesting that complication rates are not adversely affected if surgery is delayed until daylight hours.95,96 If this practice is to be considered, it needs to be balanced against the condition of the individual patient, the potential for disrupting the morning operating room schedule, and increase in the overall length of hospital stay.

The appendix can be surgically removed either through the traditional open technique or through laparoscopy. A Cochrane review of 45 randomized studies favors laparoscopic removal.97 The authors conclude that laparoscopic appendix removal results in less frequent wound infections, less postoperative pain on day 1, shorter lengths of hospital stay, shorter time to return to normal activity, and decreased overall costs. Laparoscopy may be most helpful in female patients, as it allows inspection for pelvic pathology that may masquerade as acute appendicitis.

Some institutions have developed extensive operative and postoperative guidelines for the care of appendicitis patients.98,99 Use of these guidelines has decreased postoperative complications and costs and appears to be most helpful in the subgroup of patients with perforation.

For patients with evidence of perforation and abscess formation, many surgeons prefer to nonoperatively drain the abscess and treat the patient with intravenous antibiotics initially, followed by appendectomy 6 weeks later.100 Recently, it was even suggested that the appendix may not have to be removed after successful abscess resolution.101

Disposition

If the suspicion for appendicitis is low, the patient may be sent home after appropriate counseling and arrangement of follow-up. Discharged patients should be encouraged to start on a liquid diet and advance to solids when their symptoms improve. Patients with abdominal pain of unclear cause who require significant doses of opiates to control their pain should be considered for admission.102

References

1. Körner, H, et al. Incidence of acute nonperforated and perforated appendicitis: Age-specific and sex-specific analysis. World J Surg. 1997;21:313–317.

2. Wagner, JM, McKinney, WP, Carpenter, JL. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA. 1996;276:1589–1594.

3. Brown, TW, McCarthy, ML, Kelen, GD, Levy, F. An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:553–560.

4. Seal, A. Appendicitis: A historical review. Can J Surg. 1981;24:427–433.

5. Vastag, B. Medicine on the Lewis and Clark Trail: Exhibit explores expedition’s medical adventures. JAMA; 2003;289.

6. Smith, S. Appendicitis, appendectomy and the surgeon. Bull Hist Med. 1996;70:414–441.

7. Randal Bollinger, R, Barbas, AS, Bush, EL, Lin, SS, Parker, W. Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. J Theor Biol. 2007;249:826–831.

8. Klingler, PJ, Smith, SL, Abendstein, BJ, Brenner, E, Hinder, RA. Management of ingested foreign bodies within the appendix: A case report with review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2295–2297.

9. Hadi, HI, Quah, HM, Maw, A. A missing tongue stud: An unusual appendicular foreign body. Int Surg. 2006;91:87–89.

10. Watters, JM, Blakslee, JM, March, RJ, Redmond, ML. The influence of age on the severity of peritonitis. Can J Surg. 1996;39:142–146.

11. Ramsden, WH, Mannion, RA, Simpkins, KC, deDombal, FT. Is the appendix where you think it is—and if not does it matter? Clin Radiol. 1993;47:100–103.

12. Andersson, RE, et al. Diagnostic value of disease history, clinical presentation, and inflammatory parameters of appendicitis. World J Surg. 1999;23:133–140.

13. Dixon, JM, Elton, RA, Rainey, JB, Macleod, DA. Rectal examination in patients with pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. BMJ. 1991;302:386–389.

14. Bundy, DG, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298:438–451.

15. Hale, DA, Molloy, M, Pearl, RH, Schutt, DC, Jaques, DP. Appendectomy: A contemporary appraisal. Ann Surg. 225, 1997. [252–226].

16. McLario, D, Rothrock, S. Understanding the varied presentation and management of children with acute abdominal disorders. Pediatr Emerg Med Rep. 1997 Nov.

17. Webster, DP, Schneider, CN, Cheche, S, Daar, AA, Miller, G. Differentiating acute appendicitis from pelvic inflammatory disease in women of childbearing age. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:569–572.

18. Morishita, K, Gushimiyagi, M, Hashiguchi, M, Stein, GH, Tokuda, Y. Clinical prediction rule to distinguish pelvic inflammatory disease from acute appendicitis in women of childbearing age. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:152–157.

19. Bongard, F, Landers, DV, Lewis, F. Differential diagnosis of appendicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Surg. 1985;150:90–96.

20. Al-Mulhim, AA. Acute appendicitis in pregnancy. A review of 52 cases. Int Surg. 1996;81:295–297.

21. Mourad, J, Elliott, JP, Erickson, L, Lisboa, L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: New information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1027–1029.

22. McGory, ML, et al. Negative appendectomy in pregnant women is associated with substantial risk of fetal loss. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:534–540.

23. Chung, RS, Rowland, DY, Li, P, Diaz, J. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of laparoscopic versus conventional appendectomy. Am J Surg. 1999;177:250–256.

24. Urbach, D, Cohen, M. Is the perforation of the appendix a risk factor for tubal infertility and ectopic pregnancy? An appraisal of the evidence. Can J Surg. 1999;42:101–108.

25. Andersson, R, Lambe, M, Berstrom, R. Fertility patterns after appendicetomy: A historical cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:963–967.

26. Andersson, R. Resolution and predominance of prehospital perforations imply that a correct diagnosis is more important than an early diagnosis. World J Surg. 2007;31:86–92.

27. Styrud, J, et al. Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment in acute appendicitis. A prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2006;30:1033–1037.

28. Livingston, EH, Woodward, WA, Sarosi, GA, Haley, RW. Disconnect between incidence of nonperforated and perforated appendicitis. Implications for pathophysiology and management. Ann Surg. 2007;245:886–892.

29. Abou-Nukta, F, et al. Effects of delaying appendectomy for acute appendicitis for 12 to 24 hours. Arch Surg. 2006;141:504–506.

30. Hallan, S, Asberg, A. The accuracy of C-reactive protein in diagnosing acute appendicitis—a meta-analysis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1997;57:373–380.

31. Andersson, RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28–37.

32. Grönroos, JM. Do normal leucocyte count and C-reactive protein value exclude acute appendicitis in children? Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:649–651.

33. Wu, H, Fu, Y. Application with repeated serum biomarkers in pediatric appendicitis in clinical surgery. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:161–166.

34. Malik, AA, Wani, NA. Continuing diagnostic challenge of acute appendicitis: Evaluation through modified Alvarado score. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:504–505.

35. Rao, PM, Boland, GW. Imaging of acute right lower abdominal quadrant pain. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:639–649.

36. Pouget-Baudry, Y, et al. The use of the Alvarado score in the management of right lower quadrant abdominal pain in the adult. J Visceral Surg. 2010;147:e40–e44.

37. Rao, PM, Rhea, JT, Rao, JA, Conn, AK. Plain abdominal radiography in clinically suspected appendicitis: Diagnostic yield, resource use and comparison with CT. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:325–328.

38. Lin, WY, et al. 99Tcm-HMPAO–labelled white blood cell scans to detect acute appendicitis in older patients with an atypical clinical presentation. Nucl Med Commun. 1997;18:75–78.

39. Weston, AR, Jackson, TJ, Blamey, S. Diagnosis of appendicitis in adults by ultrasonography or computed tomography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:368–379.

40. Terasawa, T, Blackmore, CC, Bent, S, Kohlwes, RJ. Systematic review: Computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537–546.

41. Lee, JH, et al. Operator-dependent techniques for graded compression sonography to detect the appendix and diagnose acute appendicitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:91–97.

42. Rice, HE, et al. Does early ultrasonography affect management of pediatric appendicitis? A prospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:754–759.

43. Rompel, O, Huelsse, B, Bodenschatz, K, Reutter, G, Darge, K. Harmonic US imaging of appendicitis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:1257–6124.

44. Incesu, L, Yazicioglu, AK, Selcuk, MB, Ozen, N. Contrast enhanced power Doppler US in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:201–209.

45. Peck, J, Peck, A, Peck, C, Peck, J. The clinical role of noncontrast helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Am J Surg. 2000;180:133–136.

46. Balthazar, EJ, Rofsky, NM, Zucker, R. Appendicitis: The impact of computed tomography imaging on negative appendectomy and perforation rates. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:768–771.

47. Albano, MC, et al. Resident interpretation of emergency CT scans in the evaluation of acute appendicitis. Acad Radiol. 2001;8:915–918.

48. Brenner, D, Elliston, C, Hall, E, Berdon, W. Estimated risks of radiation induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:289–296.

49. Berrington de González, A, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2071–2077.

50. Keyzer, C, et al. MDCT for suspected acute appendicitis in adults: Impact of oral and IV contrast media at standard-dose and simulated low-dose techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:446–454.

51. Kim, K, et al. Low-dose abdominal CT for evaluating suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1596–1605.

52. Seo, H, et al. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis with sliding slab ray-sum interpretation of low-dose unenhanced CT and standard-dose IV contrast-enhanced CT scans. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:96–105.

53. Platon, A, et al. Evaluation of a low-dose CT protocol with oral contrast for assessment of acute appendicitis. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:446–454.

54. Garcia Peña, BM, et al. Ultrasonography and limited computed tomography in the diagnosis and management of appendicitis in children. JAMA. 1999;282:1041–1046.

55. Acosta, R, Crain, EF, Goldman, HS. CT can reduce hospitalization for observation in children with suspected appendicitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:495–500.

56. Berg, ER, et al. Length of stay by route of contrast administration for diagnosis of appendicitis by computed-tomography scan. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1040–1045.

57. Jacobs, JE, et al. Acute appendicitis: Comparison of helical CT diagnosis focused technique with oral contrast material versus nonfocused technique with oral and intravenous contrast material. Radiology. 2001;220:683–690.

58. Kharbanda, AB, Taylor, GA, Bachur, RG. Suspected appendicitis in children: Rectal and intravenous contrast–enhanced versus intravenous contrast–enhanced CT. Radiology. 2007;243:520–526.

59. Kaiser, S, Frenckner, B, Jorulf, HK. Suspected appendicitis in children: US and CT—a prospective randomized study. Radiology. 2002;223:633–638.

60. Hlibczuk, V, Dattaro, JA, Jin, Z, Falzon, L, Brown, MD. Diagnostic accuracy of noncontrast computed tomography for appendicitis in adults: A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:51–59.

61. Tamburrini, S, Brunetti, A, Brown, M, Sirlin, C, Casola, G. Acute appendicitis: Diagnostic value of nonenhanced CT with selective use of contrast in routine clinical settings. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:2055–2061.

62. Daly, CP, et al. Incidence of acute appendicitis in patients with equivocal CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1813–1820.

63. Levine, CD, Aizenstein, O, Lehavi, O, Blachar, A. Why we miss the diagnosis of appendicitis on abdominal CT: Evaluation of imaging features of appendicitis incorrectly diagnosed on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:855–859.

64. Ganguli, S, Raptopoulos, V, Komlos, F, Siewert, B, Kruskal, JB. Right lower quadrant pain: Value of the nonvisualized appendix in patients at multidetector CT. Radiology. 2006;241:175–180.

65. Nikolaidis, P, Hwang, CM, Miller, FH, Papanicolaou, N. The nonvisualized appendix: Incidence of acute appendicitis when secondary inflammatory changes are absent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:889–892.

66. in’t Hof, KH, et al. Interobserver variability in CT scan interpretation for suspected acute appendicitis. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:92–94.

67. Kaiser, S, Finnbogason, T, Jorulf, HK, Söderman, E, Frenckner, B. Suspected appendicitis in children: Diagnosis with contrast-enhanced versus nonenhanced helical CT. Radiology. 2004;231:427–433.

68. Keyzer, C, et al. Normal appendix in adults: Reproducibility of detection with unenhanced and contrast-enhanced MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:507–514.

69. SCOAP Collaborative, et al. Negative appendectomy and imaging accuracy in the Washington State Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann Surg. 2008;248:557–563.

70. Mori, Y, Yamasaki, M, Furukawa, A, Takahashi, M, Murata, K. Enhanced CT in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis to evaluate the severity of disease: Comparison of CT findings and histological diagnosis. Radiat Med. 2001;19:197–202.

71. Pedrosa, I, et al. MR imaging evaluation of acute appendicitis in pregnancy. Radiology. 2006;238:891–899.

72. Oto, A, et al. Right lower quadrant pain and suspected appendicitis in pregnant women: Evaluation with MR imaging—initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234:445–451.

73. Hörmann, M, et al. MR imaging in children with nonperforated acute appendicitis: Value of unenhanced MR imaging in sonographically selected cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:467–470.

74. Pedrosa, I, Zeikus, EA, Levine, D, Rofsky, NM. MR imaging of acute right lower quadrant pain in pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Radiographics. 2007;27:721–753.

75. Leeuwenburgh, MM, et al. Optimizing imaging in suspected appendicitis (OPTIMAP Study): A multicenter diagnostic accuracy study of MRI in patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Study Protocol. BMC Emerg Med. 2010;10:19.

76. Jones, PF. Suspected acute appendicitis: Trends in management over 30 years. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1570–1577.

77. Rennie, AT, Tytherleigh, MG, Theodoroupolou, K, Farouk, R. A prospective audit of 300 consecutive young women with an acute presentation of right iliac fossa pain. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:140–143.

78. Varadhan, KK, Humes, DJ, Neal, KR, Lobo, DN. Antibiotic therapy versus appendectomy for acute appendicitis: A meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2010;34:199–209.

79. Bailey, B, Bergeron, S, Gravel, J, Bussières, JF, Bensoussan, A. Efficacy and impact of intravenous morphine before surgical consultation in children with right lower quadrant pain suggestive of appendicitis: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:371–378.

80. Green, R, Bulloch, B, Kabani, A, Hancock, BJ, Tenenbein, M. Early analgesia for children with acute abdominal pain. Pediatrics. 2005;116:978–983.

81. Ranji, SR, Goldman, LE, Simel, DL, Shojania, KG. Do opiates affect the clinical evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain? JAMA. 2006;296:1764–1774.

82. Rhea, JT, Rao, PM, Novelline, RA, McCabe, CJ. A focused appendiceal CT technique to reduce the cost of caring for patients with clinically suspected appendicitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:113–118.

83. Rao, PM, Rhea, JT, Novelline, RA, Mostafavi, AA, McCabe, CJ. Effect of computed tomography of the appendix on treatment of patients and use of hospital resources. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:141–146.

84. Rao, PM, Rhea, JT, Rattner, DW, Venus, LG, Novelline, RA. Introduction of appendiceal CT: Impact on negative appendectomy and appendiceal perforation rates. Ann Surg. 1999;229:344–349.

85. Morris, KT, et al. The rational use of computed tomography scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Am J Surg. 2002;183:547–550.

86. Reich, JD, Brogdon, B, Ray, WE, Eckert, J, Gorell, H. Use of CT scan in the diagnosis of pediatric acute appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16:241–243.

87. Ramarajan, N, et al. An interdisciplinary initiative to reduce radiation exposure: Evaluation of appendicitis in a pediatric emergency department with clinical assessment supported by a staged ultrasound and computed tomography pathway. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1258–1265.

88. Reference deleted in proofs.

89. Wilson, EB, Cole, JC, Nipper, ML, Cooney, DR, Smith, RW. Computed tomography in the diagnosis of appendicitis: When are they indicated? Arch Surg. 2001;136:670–675.

90. Flum, D, Morris, A, Koepsell, T, Dellinger, E. Has misdiagnosis of appendicitis decreased over time? A population-based analysis. JAMA. 2001;286:1748–1753.

91. Coursey, CA, et al. Making the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: Do more preoperative CT scans mean fewer negative appendectomies? A 10-year study. Radiology. 2010;254:460–468.

92. Antevil, JL, et al. Computed tomography–based clinical diagnostic pathway for acute appendicitis: Prospective validation. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:849–856.

93. Goldin, AB, Sawin, RS, Garrison, MM, Zerr, DM, Christakis, DA. Aminoglycoside-based triple-antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy in children with ruptured appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2007;119:905–911.

94. Faser, JD, et al. A complete course of intravenous antibiotics vs. a combination of intravenous and oral antibiotics for perforated appendicitis in children: A prospective, randomized trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1198–1202.

95. Ingraham, AM, et al. Effect of delay to operation on outcomes in adults with acute appendicitis. Arch Surg. 2010;145:886–892.

96. Yardeni, D, et al. Delayed vs. immediate surgery in acute appendicitis: Do we need to operate during the night? J Pediatr Surg. 2005;39:464–469.

97. Sauerland, S, Lefering, R, Neugebaur, E. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2002.

98. Helmer, KS, et al. Standardized patient care guidelines reduce infectious morbidity in appendectomy patients. Am J Surg. 2002;183:608–613.

99. Katkhouda, N, et al. Intraabdominal abscess rate after laparoscopic appendectomy. Am J Surg. 2000;180:456–461.

100. Yamini, D, Vargas, H, Bongard, F, Klein, S, Stamos, MJ. Perforated appendicitis: Is it truly a surgical urgency? Am Surg. 1998;64:970–975.

101. Ein, SH, Shandling, B. Is interval appendectomy necessary after rupture of an appendiceal mass? J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:849–850.

102. Rusnak, R, Borer, J, Fastow, J. Misdiagnosis of acute appendicitis: Common features discovered in cases after litigation. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:397–402.