65 Acute and Chronic Renal Failure

Acute Renal Failure

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Renal

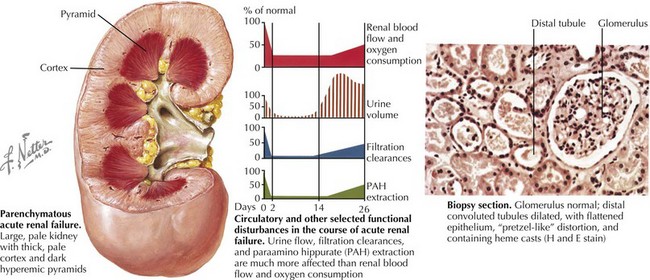

AKI (intrinsic renal disease) is the result of disorders that involve the renal vascular, glomerular, or tubular–interstitial pathology. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) results from ischemia caused by decreased renal perfusion or injury from tubular nephrotoxins (Figure 65-1). All causes of prerenal AKI can progress to ATN if renal perfusion is not restored or nephrotoxins are not withdrawn. Nephrotoxic AKI is mostly caused by toxic tubular injury by medications, including aminoglycosides, contrast agents, amphotericin B, chemotherapeutic agents (ifosfamide, cisplatin), and acyclovir. Toxic tubular injury can also be induced by the release of heme pigments, as it occurs from myoglobinuria caused by rhabdomyolysis and hemoglobinuria caused by intravascular hemolysis. Uric acid nephropathy and tumor lysis syndrome are causes of AKI in children with leukemia. During chemotherapy, a rapid breakdown of tumor cells causes increased release and subsequent excretion of uric acid, resulting in precipitation of uric acid crystals in the tubules and renal microvasculature. Hyperphosphatemia in tumor lysis syndrome results in precipitation of calcium phosphate crystals in the tubules. Acute interstitial nephritis most commonly results from hypersensitivity reactions to drugs, including penicillin analogs (e.g., methicillin), cimetidine, sulfonamides, rifampin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and proton pump inhibitors, but can also be idiopathic. Glomerulonephritis of any etiology (including those caused by vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or Goodpasture’s syndrome) may present with AKI, with postinfectious glomerulonephritis being the most common cause of AKI in this group. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis presents as the most severe degree of any form of glomerulonephritis and presents with AKI. Vascular causes of AKI include cortical necrosis (mostly caused by hypoxic or ischemic injury in newborns), renal artery or vein thrombosis, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS).

Clinical Presentation

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Serum Creatinine Concentration, Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers, and Classification of Acute Kidney Injury

Fractional Excretion of Sodium

Renal Imaging

Renal ultrasonography should be performed in all children with AKI. It can document the presence of one or two kidneys, determine renal size (often enlarged in those with AKI) (see Figure 65-1), assess the renal parenchyma, and diagnose urinary tract obstruction or occlusion of the major renal vessels.

Prevention and Management

The basic principles of the general management of AKI are shown in Box 65-1.

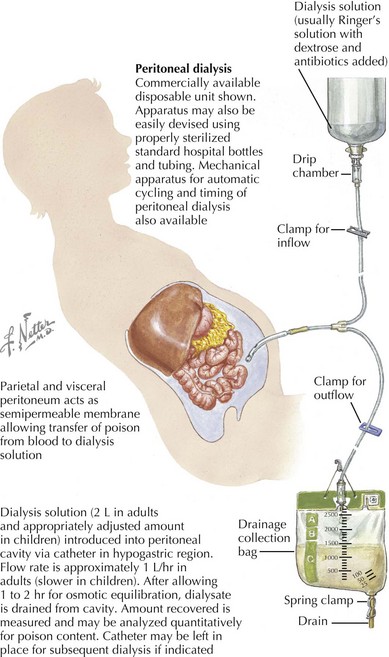

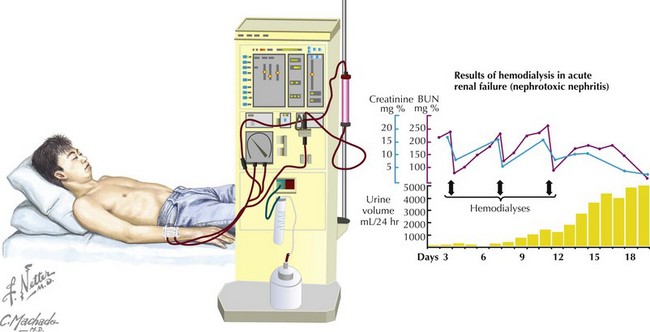

Renal Replacement Therapy

Renal replacement therapy in children with AKI should be initiated for the indications listed in Box 65-2.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Etiology and Pathogenesis

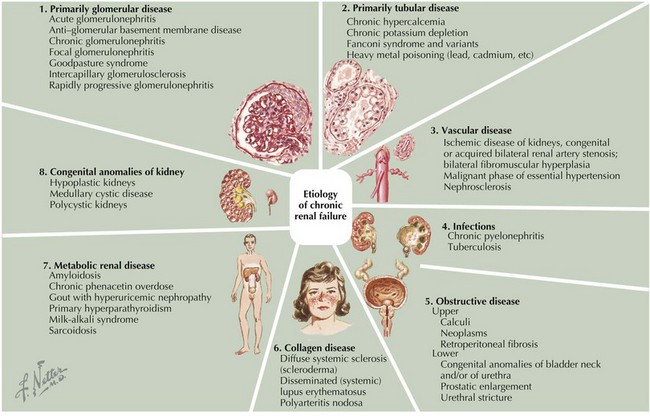

Based on the registry of the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies, the causes of CKD are as follows: Congenital renal anomalies are present in 57% of cases (obstructive uropathy; renal aplasia, hypoplasia, or dysplasia; reflux nephropathy; and polycystic kidney disease), and glomerular disease is present in 17% of cases, with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) being the most common glomerular disorder (9% of all CKD cases; African American children are three times more likely to develop FSGS than white children). Other causes accounted for 25% of cases and included HUS, genetic disorders (e.g., cystinosis, oxalosis, hereditary nephritis), and interstitial nephritis. In large number of cases (18%), the primary disease is unknown because patients present in late stages of CKD. Unlike in adults, diabetic nephropathy and hypertension are rare causes of CKD in children (Figure 65-2).

Clinical Presentation

Complications

Evaluation

Laboratory Testing

There is no single pattern of laboratory abnormalities that characterizes pediatric CKD, but some abnormalities are commonly present and are indicative of underlying chronic kidney dysfunction. Serum creatinine is the most commonly used test to estimate the GFR (creatinine clearance indirectly represents the GFR) using the Schwartz formula: GFR = kL/SCr, where k is a constant that varies with age and sex, L is length (cm), and SCr is serum creatinine in mg/dL (Table 65-1). The GFR is then used to determine the stage of CKD. Normal levels of GFR vary with age, gender, and body size (Table 65-2). GFR increases with maturation from infancy and approaches adult mean value by 2 years of age.

Table 65-1 Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease for Children Older Than 2 Years of Age

| Stage | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

|---|---|

| 1 | Normal (≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2) |

| 2 | 60-89 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| 3 | 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| 4 | 15-29 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| 5 | <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or ESRD |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Table 65-2 Normal Glomerular Filtration Rate Levels and the Schwartz Equation

| Age (Gender) | Schwartz Equation (Serum Creatinine in mg/dL, Length in cm) | Mean GFR ± SD (mL/min/1.73m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 wk (boys and girls) | GFR = 0.33*(Length/SCr) in preterm infants | 40.6 ± 14.8 |

| GFR = 0.45*(Length/SCr) in term infants | ||

| 2-8 wk (boys and girls) | GFR = 0.45*(Length/SCr) | 65.8 ± 24.8 |

| >8 wk (boys and girls) | GFR = 0.45*(Length/SCr) | 95.7 ± 21.7 |

| 2-12 y (boys and girls) | GFR = 0.55*(Length/SCr) | 133.0 ± 27.0 |

| 13-18 y (boys) | GFR = 0.70*(Length/SCr) | 140.0 ± 30.0 |

| 13-18 y (girls) | GFR = 0.55*(Length/SCr) | 126.0 ± 22.0 |

GFR, glomerular filtration rate; SCr, serum creatinine; SD, standard deviation.

Management

Management of Complications

Renal Replacement Therapy

Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis LL, et al. Modified RIFLE criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2007;71(10):1028-1035.

Andreoli SP. Acute kidney injury in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(2):253-263.

Andreoli SP. Management of acute kidney injury in children: a guide for pediatricians. Paediatr Drugs. 2008;10(6):379-390.

Benfield MR, Bunchman TE. Management of acute renal failure. In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, editors. Pediatric Nephrology. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1253-1266.

Eddy AA. Progression in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12:353.

Fine RN, Whyte DA, Boydstun II. Conservative management of chronic renal insufficiency. In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, editors. Pediatric Nephrology. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1253-1266.

Greenbaum LA. Anemia in children with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12(4):385-396.

Hadtstein C, Schaefer F. Hypertension in children with chronic kidney disease: pathophysiology and management. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(3):363-371.

Nguyen MT, Devarajan P. Biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(12):2151-2157.

Srivastava T, Warady BA: Overview of the management of chronic kidney disease in children, UpToDate 17.1, 2009.

Wesseling K, Bakkaloglu S, Salusky I. Chronic kidney disease mineral and bone disorder in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(2):195-207.

Wong CS, Warady BA: Epidemiology, etiology, and course of chronic kidney disease in children. UpToDate 17.1, 2009.

Wong CS, Warady BA, Srivastava T: Clinical presentation and evaluation of chronic kidney disease in children. UpToDate 17.1, 2009.