Chapter 7 ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

INTRODUCTION

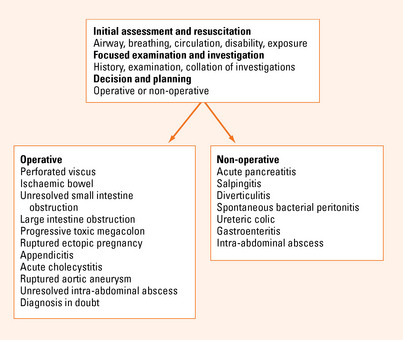

Acute abdominal pain should always be considered a surgical condition. The management of the patient with acute abdominal pain can be simplified by considering appropriate clinical management pathways and not focusing on the final diagnosis. The key to this is the use of clinical symptoms and signs in combination with limited special tests to decide if the patient is best treated by urgent or planned operation or conservative management. Many of these immediate decisions can be made by the bedside with a good history and examination.

CAUSES OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Generalised abdominal pain

Constant abdominal pain

In a patient with generalised constant abdominal pain and abdominal rigidity, the working diagnosis is peritonitis. This is always secondary to some other process. Often, but not always, this is due to a perforated viscus. The role of surgery is to provide peritoneal toilet and to prevent ongoing contamination by removing or repairing the perforated viscus. There are a number of conditions that fulfill this criterion. There are other conditions, however, that may demonstrate the signs of peritonitis but not require intervention (see Figure 7.1). Typically acute pancreatitis with generalised inflammation may have tenderness and guarding but does not require a laparotomy. A diagnostic elevated lipase may be very useful in this setting. In females, pelvic inflammatory disease may show generalised signs and does not benefit from laparotomy as there is no ongoing contamination. This should be considered in appropriate clinical contexts. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in portal hypertension should also be considered in patients presenting with generalised abdominal pain and portal hypertension with ascites.

Beware of the patient complaining of severe constant generalised abdominal pain who appears to have a relatively soft ‘doughy’ abdomen to palpation. This patient may have ischaemic bowel. Suspicion may be raised if they have bloody diarrhoea and atrial fibrillation. Investigations may reveal an elevated white cell count and a metabolic acidosis. Venous obstruction is often more subtle and slowly progressive.

Colicky abdominal pain

In contrast, a bowel obstruction will usually be associated with vomiting and constipation with progressive abdominal distension. The higher the obstruction is anatomically in the intestine, the earlier the vomiting and the later the constipation. The more distal the obstructing lesion, the greater the distension. A supine and erect plain abdominal film will usually confirm the diagnosis. An erect chest X-ray should always be ordered to look for free peritoneal gas. The supine abdominal film is the most useful. With the patient lying flat it will not show the fluid levels of the erect film but it will show gaseous distended bowel down to the level of obstruction. The ileum or small intestine can be distinguished by its central position and valvulae conniventes extending across the intestinal lumen. The jejunum or large intestine is distinguished by its incomplete valves and more peripheral position.

Localised abdominal pain

It is best to consider these conditions in relation to the position in the abdomen in which the signs occur.

Right iliac fossa

Any patient who complains of periumbilical pain that radiates to the right iliac fossa should be considered to have appendicitis until proven otherwise. The patient will usually have a low-grade fever and anorexia with an elevated white cell count and significant tenderness in the right iliac fossa. Abdominal imaging is usually not required in such a patient although a pelvic ultrasound may be considered in a female if a ruptured ovarian cyst is considered. Initial periumbilical pain does not usually occur in primary pelvic pathology.

ASSESSMENT

History

The presence of colic and duration of symptoms will differentiate between viscus obstruction and inflammation. The presence of vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation and a previous history suggests bowel obstruction.

MANAGEMENT

The approach to managing the patient should be performed in three steps:

Immediate assessment and management

This is really the initial resuscitation phase and should stabilise the patient’s airway, breathing and circulation. This phase should only take a few minutes. If the patient can speak then the airway is clear, if not the airway will need to be secured and oxygen applied. Breathing is the mechanical act of ventilation and may be compromised by altered consciousness or a splinted diaphragm due to severe abdominal pain. Circulation may be compromised by sepsis or dehydration. Venous access should be achieved by a large bore peripheral cannula, bloods drawn for assessment and a crystalloid fluid administered. A bolus of 10 mL/kg should be administered initially. If the patient is hypoperfused, the bolus should be increased to 20 mL/kg. Next the level of consciousness and mental state of the patient should be documented. The patient should be exposed for any obvious finding, such as distension, and then covered to keep them comfortable.

Decision and plan of management

Initially it must be decided if the patient requires immediate surgery, delayed surgery or observation with conservative management and further investigations. If immediate surgery is required, it should be established whether there is time or the need for preoperative stabilisation. The patient with a bleeding condition, such as a ruptured aortic aneurysm or ruptured ectopic pregnancy or a perforated viscus, is often best managed by urgent surgical intervention with no delay. Further resuscitation can occur while surgery is performed. A delay in intervention in these conditions is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Abu-Yousef MM, Bleicher JJ, Maher JW. High resolution sonography of acute appendicitis. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:53-58.

Anderson ID. Care of the critically ill surgical patient, 2nd edn. London: Arnold; 2003.

Dang C, Aguilera P, Dang A. Acute abdominal pain. Geriatrics. 2002;57:30-42.

Davidson SJ, Murphy DG, Barbaro G. Missed diagnosis of acute cardiac ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1492-1494.

Oria A, Cimmino D, Ocampo C, et al. Early endoscopic intervention versus early conservative management in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis and biliopancreatic obstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:10-17.

Thomas SH, William S, Cheema F. Effect of morphine analgesia on diagnostic accuracy in emergency department patients with abdominal pain. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:18-31.