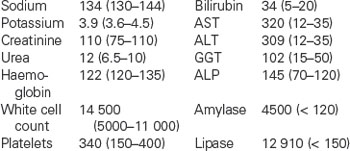

4 Acute abdominal pain

Case

A 72-year-old previously well woman presents with a 12-hour history of severe epigastric pain radiating to her back. There has been associated nausea and vomiting, but no fevers, jaundice or rigors. Until the onset of pain her bowel habit was unchanged and there were no complaints of abdominal distension. She has had no significant previous illness or surgery. She does not drink alcohol and does not smoke cigarettes. There was a strong family history of gallstones with her mother and two sisters having had surgery for gallstones.

Introduction

Acute abdominal pain is defined as recent onset pain of such severity that medical attention is usually sought shortly after its onset. For the purpose of definition, pain persisting for up to 3 months is classified as acute; pain lasting more than 3 months is classified as chronic and is considered in Chapters 5 and 6.

Pathological Causes

Acute inflammation

Inflammation of intraperitoneal organs

Acute inflammation of an intraperitoneal organ results in localised peritonitis if the process involves its peritoneal surface. Ensuing pain results from irritation of pain receptors in the parietal (but not visceral) peritoneum. This pain is described as peritoneal in type. Peritoneal pain is well localised; the patient can usually indicate its position with the palm of a hand or with the tip of a finger. The pain is typically aggravated by sudden movement, such as coughing, and minimised by avoidance of movement, such as lying still or using the diaphragmatic rather than the abdominal muscles for respiration. As an example, involvement of a segment of bowel with Crohn’s disease, a transmural inflammatory process, can result in peritoneal pain. Inflammation restricted to bowel mucosa, as typically occurs in ulcerative colitis, does not result in peritoneal pain (Ch 12).

Intraperitoneal inflammation may be a consequence of perforation of a hollow viscus. Leakage of visceral contents causes pain by chemical irritation. The degree of irritation is dependent on the nature of the leaking material. Thus, leaking gastric juice from a perforated peptic ulcer causes marked irritation. By contrast, gas, which may be the main constituent of the material leaking from a perforated sigmoid diverticulum, causes less irritation and less pain. As the inflammation in response to chemical irritation is rapid, the onset of the pain is rapid or instantaneous. Whether the pain is localised or generalised depends on the degree of soilage. Maximum irritation is usually around the site of leakage (e.g. epigastric for a perforated peptic ulcer and in the left iliac fossa for a perforated sigmoid diverticulum). Other causes of perforation include ischaemia that has progressed to infarction (e.g. gangrenous cholecystitis) and malignancy (e.g. perforated gastric cancer).

Ischaemia

The process of venous ischaemia is slower in onset. Consequently, the pain is slower in onset. Otherwise, it has the same characteristics as the pain of arterial ischaemia. When the venous occlusion is complete, as occurs to a loop of bowel strangulated by the neck of a hernia, the tissue drained by the occluded vein becomes oedematous and engorged with blood, and arterial obstruction and thrombosis may follow (Fig 4.1). With larger vein occlusion by a thrombus (e.g. the portal or the superior mesenteric vein, or occasionally with a volvulus of bowel), the occlusion may be incomplete and alternative venous drainage may save the tissue from necrosis. Acute major mesenteric venous obstruction causes transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity, which may be evident as ascites.

Tension in a solid organ

Sudden swelling in solid organs results in a pain of visceral type due to stretching of the capsule of the organ. The pain is dull and constant. The severity of the pain depends on the speed and degree of swelling. Examples include haemorrhage into an ovarian cyst, necrosis of a hepatic metastasis and hepatic venous engorgement due to acute right heart failure.

Clinical Evaluation

A simple practical approach to diagnosis of acute abdominal pain involves stratification as shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Sites and types of abdominal pain related to different organs

| Position of pain | Nature or type of pain |

|---|---|

| Generalised Localised, e.g.: |

Peritoneal

Colicky

Clinical evaluation is performed with the knowledge that many of the patients who present with acute abdominal pain have a short-term, self-limiting illness for which nothing more than symptomatic and supportive treatment is required. Selection bias results in this proportion being small in patients admitted to hospital, larger in patients presenting to emergency units and largest in general practice. A list of causes of non-trauma-related abdominal pain seen in an English hospital is shown in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Causes of abdominal pain seen at a hospital emergency unit

| Cause | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Non-specific abdominal pain | 34 |

| Acute appendicitis | 28 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 10 |

| Small bowel obstruction | 4 |

| Acute gynaecological disease | 4 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3 |

| Renal colic | 3 |

| Perforated peptic ulcer | 2 |

| Cancer | 2 |

| Diverticular disease | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | 9 |

From de Dombal FT. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1991, with permission.

Generalised Abdominal Pain

The common causes of generalised acute abdominal pain are listed in Table 4.3. The first issue to address is whether or not the patient has an abdominal catastrophe. On most occasions, differentiation of a patient with an abdominal catastrophe from one with non-specific abdominal pain is relatively straightforward. As indicated in Table 4.3, the patient with an abdominal catastrophe usually has generalised peritonitis, with generalised tenderness, guarding, rebound tenderness and absence of bowel sounds. However, there may be few signs initially to accompany a mesenteric embolus or thrombosis while the bowel is still viable. Further, the abdominal signs associated with acute pancreatitis may be mild.

Table 4.3 Causes and clinical features of conditions producing generalised acute abdominal pain

| Cause | Abdominal signs | Associated signs |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific abdominal pain | Nil or mild | Nil |

| Perforated appendix | Generalised peritonitis, more tender in the right iliac fossa | ± shock |

| Perforated diverticulum | Generalised peritonitis, possibly more tender in the left iliac fossa | ± shock |

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy | Generalised peritonitis | ± shock |

| Ruptured pathological solid organ | ± mass/organomegaly | ± shock |

| Ruptured aortic aneurysm | Tender pulsatile mass | Shock |

| Strangulated bowel | Focal or generalised peritonitis | Bowel obstruction ± sepsis ± shock |

| Superior mesenteric thrombosis or embolus | Initially few or no signs (pain out of proportion to signs) | Atrial fibrillation or myocardial infarction ± shock |

| Ischaemic colitis | Often not severe unless there is transmural infarction | Bloody diarrhoea, atrial fibrillation or myocardial infarction |

| Pancreatitis | May be few signs (pain can be out of proportion to signs) | ± shock |

The previous history and associated signs that may be of help in distinguishing the various catastrophes are listed in Table 4.4.

Table 4.4 Clinical clues to establish the cause of the abdominal catastrophe

| Abdominal catastrophe | Previous history | Possible differentiating signs |

|---|---|---|

| Perforated peptic ulcer | Dyspepsia or proven peptic ulcer |

Other history of vascular disease

Vascular disease elsewhere

Previous abdominal surgery

Abdominal scars

Myocardial infarction

Other vascular disease

Recent period of low cardiac output

Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms

Signs maximal on the left side

Gallstones

The investigations that are usually performed are listed in Table 4.5. They include tests aimed at establishing the diagnosis and tests to assist resuscitation. Air under the diaphragm suggests a perforated viscus. It is most commonly present with a perforated peptic ulcer (80% of cases), less commonly present with a perforated diverticulum (20%) and rarely present with a perforated appendix. An amylase and lipase estimation is essential in all patients with generalised abdominal pain to avoid an inadvertent laparotomy for acute pancreatitis.

Table 4.5 Investigations for patients with acute generalised abdominal pain

| Investigation | Possible findings |

|---|---|

| Routine | |

| Erect chest x-ray | |

| Erect and supine abdominal x-ray | |

| Haemoglobin | |

| White cell count with differential | Leucocytosis with left shift |

| Electrolytes | Unexpected hypokalaemia |

| Urea and creatinine | Unexpected renal failure |

| Serum amylase Serum lipase |

|

| Under appropriate clinical circumstances | |

| Limited gastrograffin meal | Confirmation of duodenal perforation if conservative treatment is contemplated |

| Beta human chorionic gonadotropin | Elevated in ectopic pregnancy |

| Abdominal ultrasound | Confirmation of ruptured aneurysm only if diagnosis in doubt and condition is stable;demonstration of intraabdominal fluid |

| CT scan | Confirmation of ruptured aneurysm only if diagnosis in doubt and condition is stable; confirmation of pancreatitis if doubt exists; confirmation of perforated bowel to plan intervention |

| Limited gastrograffin enema | ‘Thumb printing’ due to mucosal oedema |

Specific management of conditions causing generalised abdominal pain

Perforated peptic ulcer

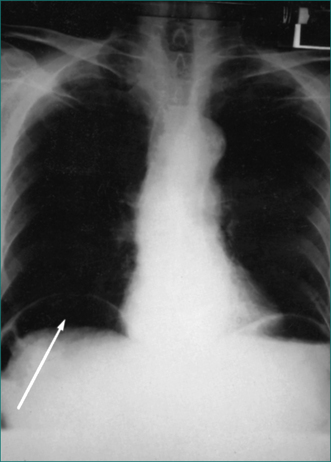

This is diagnosed by a sudden history of generalised severe abdominal pain of peritoneal type. The onset is usually instantaneous, with the patient able to recall exactly what he or she was doing at the time of onset of pain. On examination there is generalised tenderness and guarding, usually maximal in the epigastrium, board-like rigidity, loss of bowel sounds and loss of liver dullness to percussion. The diagnosis is supported by demonstration of gas under the diaphragm on an erect chest x-ray examination (Fig 4.2). A CT scan is more sensitive at detecting extraluminal (free) gas. If still uncertain, the diagnosis can be made with a limited gastrograffin meal or a laparoscopy.

Initial treatment includes fluid resuscitation, nasogastric suction and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Thereafter, the perforation can be closed either laparoscopically or at open laparotomy. The peritoneal cavity is lavaged at the same time. Closure of the perforation is required to prevent continuing contamination of the peritoneal cavity. Laparoscopic closure of the perforation and lavage of the peritoneal cavity to prevent subsequent intraabdominal abscess formation is the therapy most commonly advocated.

There is no need to perform a definitive antiulcer operation, as the ulcer diathesis can be cured after recovery from the perforation with medication (see Ch 5).

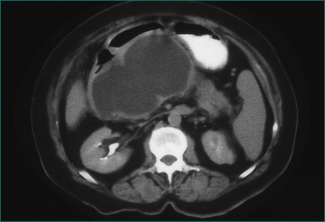

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

The clinical picture is quite different to the conditions above. The patient is usually elderly with risk factors for vascular disease. The pain is central, constant, non-peritoneal in type and often radiates through to the back. Cardiovascular collapse is a prominent feature. A tender, pulsatile epigastric mass is diagnostic. Signs of peritonism are not prominent. If the diagnosis is not made on clinical grounds and the patient is haemodynamically stable, the diagnosis may be made by CT scan, which shows retroperitoneal extravasation of blood as well as the aneurysm (Fig 4.3). Vascular grafting or stenting of the affected segment is urgently required.

Strangulated bowel

The diagnosis may not be suspected prior to laparotomy, which is performed because of severe pain unrelieved by narcotics in a patient with signs of peritonitis. The site of maximal symptoms and signs is dependent on the position of the strangulated loop of bowel. There may be associated symptoms and signs of small bowel obstruction. On plain radiology of the abdomen, the strangulated loop may be seen as thick-walled due to oedema. In addition, there may be radiological features of small bowel obstruction (see Fig 4.4). CT scanning prior to surgery may assist with the diagnosis, and even define the cause of the strangulation.

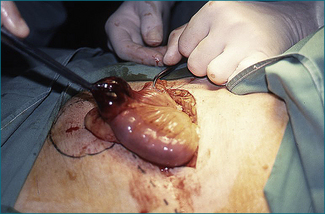

Local resection is required if the loop of bowel remains non-viable after it is released intraoperatively (Fig 4.1). Bowel that is pink in colour and exhibits spontaneous peristalsis or peristalsis when stimulated is viable. Further, there should be pulsatile flow of bright red blood through feeding vessels.

Small bowel ischaemia

Revascularisation of the bowel may be achieved with percutaneous therapeutic procedures that involve clot dissolution and possible stenting of the superior mesenteric artery. This would then be followed by an urgent laparotomy to assess the viability of the bowel.

There are two initial therapeutic options for extensive small bowel infarction:

After initial surgical recovery, there is gut adaptation and hypertrophy sufficient to allow maintenance of nutrition by oral means if the residual small bowel length is greater than 45 cm. Patients with shorter residual lengths usually require long-term parenteral nutrition (Ch 17).

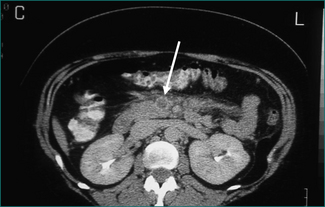

Superior mesenteric venous thrombosis usually results in a more subacute presentation. There can be associated ascites. The demonstration of a venous filling defect on the CT scan confirms the diagnosis (Fig 4.5). Management is determined by whether the affected bowel is viable or not. If the diagnosis can be made by CT scan and there are no signs of peritonism, the patient can be managed by anticoagulation and observation. Prior to commencement of anticoagulation therapy a predisposing cause is sought. Predisposing causes include the oral contraceptive pill, factor V Leidin mutation, antiphospholipid syndrome, antithrombin III deficiency, and protein S and protein C deficiency.

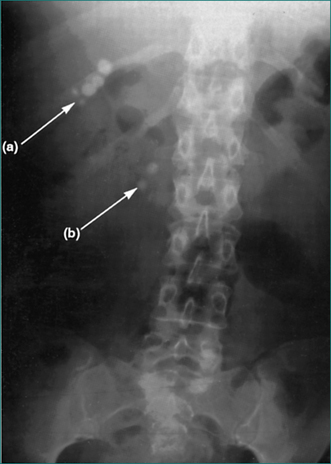

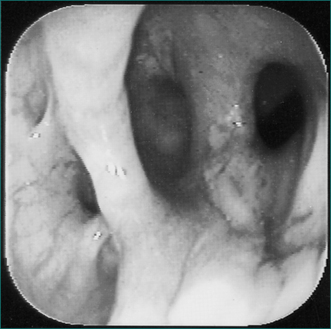

Ischaemic colitis

This condition is associated with severe central and lower abdominal pain, in association with risk factors for vascular disease and is often associated with bloody diarrhoea. There may be localised signs in the left iliac fossa or generalised signs of diffuse tenderness. The clinical diagnosis is supported by the finding of gross oedema and ‘thumb printing’ in the left colon on plain abdominal x-ray examination (see Fig 4.6) or CT scan. If there is uncertainty, colonoscopy can be helpful. Ischaemic colitis often settles with non-operative treatment. If during close observation, however, the abdominal signs become more marked or the patient develops systemic signs of sepsis, laparotomy is required to exclude an occult perforation and resect the ischaemic segment as a Hartmann’s procedure. Reanastomosis is then delayed until after full recovery. Anticoagulation treatment is contraindicated early because of the risk of massive colonic haemorrhage.

Acute Abdominal Colic

The causes of acute abdominal colic are listed in Box 4.1. The common causes are acute gastroenteritis, food poisoning, constipation and uterine disorders. The life-threatening causes are small and large bowel obstruction.

The initial clinical question is: does this patient have an innocent or a serious cause of abdominal colic? Acute gastroenteritis is usually of viral origin, is associated with diarrhoea and is infectious so that it is likely to have affected others in the household. Food poisoning can usually be related to ingestion of a particular meal. The specific management of the problems that cause abdominal colic with diarrhoea is covered in Chapter 13. Simple analgesics are part of the management.

Constipation of recent origin can often be related to ingestion of drugs (e.g. codeine-containing analgesics) or a change in dietary pattern (Ch 11). It is managed with simple analgesics, elimination of an identifiable cause and use of a bulking agent.

Bowel obstruction

The most common cause of small bowel obstruction is adhesions from a previous laparotomy. The next commonest cause is hernia, usually inguinal or femoral hernia (Ch 21). As well as eliciting the symptoms of obstruction, it might be possible to elicit the cause from the history (see Box 4.1).

Physical examination is directed to the demonstration of:

Specific investigations include the following:

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (also called Ogilvie’s syndrome) occurs most often in patients in hospital secondary to conditions such as sepsis, acute pancreatitis, electrolyte imbalance, renal failure, spinal cord injury, hip fractures, hip replacement surgery or postoperatively.

Continued competence of the ileocaecal sphincter prevents retrograde decompression of obstructed large bowel into the small bowel in more than 50% of patients, effectively producing a closed loop. Colonic distension proximal to the site of obstruction is greatest in the caecum and ascending colon. Perforation is usually heralded by localised overlying tenderness. The other useful marker of imminent perforation is colonic distension greater than 10 cm as assessed by plain abdominal x-ray examination (Fig 4.8). A sigmoid or caecal volvulus is also a closed loop that may perforate if neglected.

Diagnosis and management of large bowel obstruction

Colon cancer is discussed in detail in Chapter 22. Presentation with complete obstruction is usually preceded by fluctuating incomplete obstruction for several weeks. The tumour is more commonly in the sigmoid or descending colon. The patient may also have noted rectal bleeding. The level of the obstruction may be evident on plain abdominal radiology (see Fig 4.9). Further management is dependent upon whether the obstruction is left-sided or right-sided. An obstructing cancer in the right hemicolon can be resected with immediate re-anastomosis. An obstructing left-sided colon cancer may be managed initially with an endoscopically placed expanding metal stent (Fig 4.9) to decompress the colon. The patient is then assessed for definitive care (Ch 22). If stenting is not available the bowel can be resected with immediate re-anastomosis if all the proximal colon is resected. If a more limited resection is to be performed in mechanically unprepared bowel, and an anastomosis is performed, either a covering colostomy or ileostomy, or an intraoperative antegrade colonic washout is required. Another approach is to resect the tumour and exteriorise the proximal end as a colostomy (Hartmann’s procedure). If the tumour is associated with extensive distant metastases, a colonoscopically delivered expanding metal stent may be the definitive treatment.

The typical patient with a sigmoid volvulus is elderly, has chronic constipation and is institutionalised. The patient usually has gross abdominal distension but little vomiting and abdominal pain. The clinical diagnosis is confirmed with a plain abdominal x-ray examination, which has a typical appearance (see Fig 4.10). The single loop based in the left iliac fossa can extend to the right upper quadrant. The volvulus is decompressed using either a rigid or flexible sigmoidoscope by gently passing a soft rectal tube under direct vision through the point of the rotation at the level of the brim of the pelvis. The torted colon usually reduces spontaneously over 2–5 days, after which the rectal tube can be removed. As the condition is commonly recurrent, an elective resection of the redundant colon on its long mesentery is advisable unless contraindicated by other medical problems.

A caecal volvulus involves the caecum, the ascending colon and the terminal ileum, which rotate on a long mesentery. Typically it affects younger and fitter patients. Radiologically the volvulus extends from the right iliac fossa towards the splenic flexure (Fig 4.11). The volvulus cannot be reduced radiologically, but may be reduced using the flexible colonoscope. Operative reduction and right hemicolectomy can then be performed electively.

Gastric outlet obstruction

After gastric decompression the cause should be defined by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. If active peptic ulceration is found, the gastric outlet obstruction is potentially reversible. Healing the ulcer with parenteral acid suppression may result in resolution of oedema around the ulcer and restitution of luminal patency. Otherwise, the stomach needs to be drained surgically. If the cause is peptic ulceration, this is done by vagotomy and distal gastric resection or gastroenterostomy depending on the position of the ulcer. If the cause is gastric malignancy, this is done by distal gastric resection if the tumour is potentially curable, or gastroenterostomy or insertion of an expanding metal stent if it is not curable (see Ch 17). When the cause is a pancreatic or duodenal malignancy resection should be considered. When the lesion is not resectable resolution of the obstruction may be achieved with an endoscopic expanding metal stent or operative gastroenterostomy.

Acute Epigastric Pain

Acute epigastric pain is a common complaint. Often the pain is short-lived and no organic cause is found. A list of causes is shown in Box 4.2. On the basis of an initial clinical evaluation the clinician must decide if:

There are few features that assist in differentiating specific from non-specific causes. The severity tends to be greater and continuous with organic causes. Radiation of pain to the back is supportive of pancreatitis or biliary stone disease. Migration to the right upper quadrant suggests cholecystitis. Migration around the side to the scapula or through to the back also suggests gallstones. Associated jaundice may indicate a stone in the common bile duct (Ch 23).

On many occasions deep epigastric tenderness is the only abdominal sign. If there is focal epigastric peritonism, or more generalised peritonism, a perforated peptic ulcer or acute pancreatitis becomes more likely. The abdominal signs with acute pancreatitis may be unimpressive. Right upper quadrant tenderness or mass suggests a biliary cause for the epigastric pain.

Initial investigations

A routine initial screen includes plain radiology of the chest and abdomen, a blood film looking for anaemia and leucocytosis, liver function tests looking for evidence of hepatobiliary disease, and serum amylase and lipase. A marginal elevation of serum amylase (100–400 U/L) is not specific for pancreatitis. While an elevated lipase is more sensitive in acute pancreatitis it is also elevated in many other acute abdominal conditions and therefore is a less specific test for acute pancreatitis. Some uncommon but significant radiological signs are listed in Table 4.6. Basal pulmonary consolidation may rarely present with abdominal pain.

Table 4.6 Specific radiological findings to be looked for in acute epigastric pain

| Sign | Possible cause | Figure |

|---|---|---|

| Gas under the diaphragm | Perforated peptic ulcer | 4.2 |

| Radio-opaque gallstones | Biliary disease | 4.7 |

| Colonic cut-off sign | Acute pancreatitis | |

| Sentinel loop | Acute pancreatitis | |

| Pancreatic calcification | Chronic pancreatitis | 4.12 |

Further investigations

The need to proceed with further investigation as either an inpatient or an outpatient depends on the degree of clinical suspicion that an organic cause will be found. For many, symptomatic treatment with antacids or antispasmodics or just simple analgesics is sufficient. The next tier of investigations includes upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and upper abdominal ultrasound. The order in which they are performed depends on the clinical features. The management of abnormalities found on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is discussed under dyspepsia (see Ch 6). Hepatobiliary abnormalities found on ultrasound examination are discussed in the next section on right upper quadrant pain and also in Chapter 26.

Acute Pancreatitis And Its Complications

Aetiology

The causes of acute pancreatitis are listed in Table 4.7. The most common causes are passage of gallstones down the common bile duct and alcohol abuse. Pointers towards gallstones as the cause include female gender, older age and abnormal liver function tests.

| Cause | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Gallstones | 50–60% |

| Alcohol | 30–40% |

| Idiopathic | 10% |

| Post-ERCP | 2% |

| Medications, e.g. azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, frusemide. hydrochlorothiazide, tetracycline, sulfonamides, oestrogens, sodium valproate, L-asparaginase | Uncommon |

| Major abdominal trauma | Variable |

| Mumps | Rare |

| Hyperlipidaemia | Rare |

| Hypercalcaemia | Rare |

| Hereditary (familial) | Rare |

| Pancreatic tumours | Rare |

ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Diagnosis

Detection of elevated serum amylase levels is the usual means of diagnosis. The level rises within 12 hours of the onset of pain and gradually returns to normal over the next week. This test has a number of false positive and false negative results. False positive results include perforation of stomach or small bowel, small bowel obstruction, mesenteric ischaemia, acute cholecystitis or common bile duct obstruction, morphine, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, end-stage renal failure and chronic alcoholism. Minor elevations can occur with parotitis, tumours (lung, oesophagus, ovarian and breast carcinoma), acute or chronic liver disease, diabetic ketoacidosis and HIV infection. Macroamylasaemia is rare; there are macromolecular aggregates of amylase or IgA and amylase that are not filtered by the kidneys so that the amylase-creatinine clearance is abnormally low.

Assessment of severity

The height of the peak in serum amylase or serum lipase levels provides no useful measure of the severity of an attack of pancreatitis. Severity is scored by a combination of predominantly laboratory measurements (see Table 4.8) during the first 48 hours of hospitalisation, and this provides prognostic guidance. Severe pancreatitis is present if there are three or more poor prognostic factors. The mortality rate in cases of mild pancreatitis (less than three poor prognostic factors) is less than 1%, whereas the mortality with severe pancreatitis is greater than 50%.

Table 4.8 Poor prognostic factors for acute pancreatitis according to the Glasgow scoring system

| Factor | Critical value |

|---|---|

| Age | > 55 years |

| AST/ALT | > 200 IU/L |

| White cell count | > 15 × 109/L (15,000/mm3) |

| Serum glucose | > 10 mmol/L |

| Blood oxygen (PaO2) | < 60 mmHg |

| Blood pH | < 7.35 |

| Serum urea | > 16 mmol/L |

| Serum albumin | < 32 g/L |

| Serum calcium | < 2 mmol/L |

| Serum lactic dehydrogenase | > 600 U/L |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase.

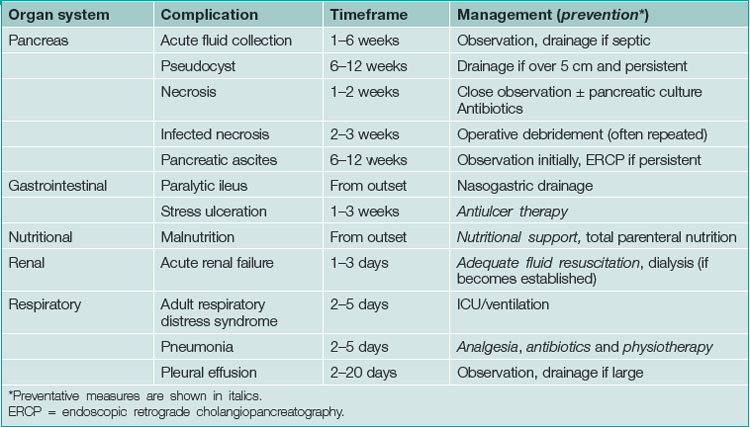

Initial management

Non-operative management is supportive and directed towards the prevention and treatment of complications. The complications of acute pancreatitis, the timeframe of their development and methods for prevention or treatment are listed in Table 4.9.

Severe pancreatitis

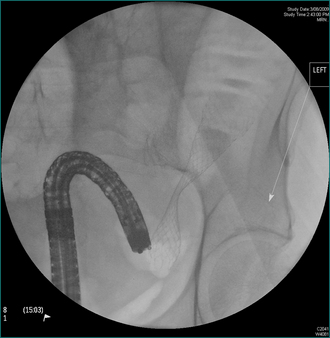

The mortality and the morbidity in acute severe gallstone pancreatitis, as defined by the presence of three or more poor prognostic factors (see Table 4.8), can be reduced by urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy. Thus an abdominal ultrasound is performed early in the admission to diagnose gallstones and if the pancreatitis is rated as severe an ERCP is performed urgently.

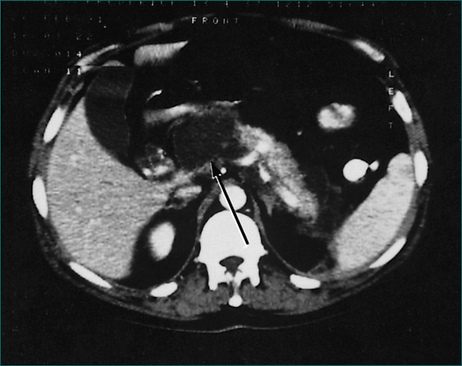

Pancreatic necrosis

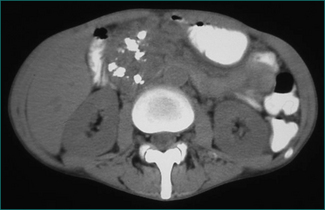

The chance of failure of early resolution of pancreatitis, and of development of complications, rises if pancreatic necrosis develops. This complication is usually apparent within 5 days of the onset of the attack if it is going to occur. Pancreatic necrosis is a radiological diagnosis made on a contrast-enhanced CT scan and is evident as unperfused tissue (see Fig 4.12). Its incidence is high in patients who present with three or more poor prognostic signs. It should also be suspected in patients whose pancreatitis fails to settle clinically within a week. Pancreatic necrosis takes 5–10 days to develop so, unless otherwise indicated, a CT scan to establish the presence of necrosis should be performed after the seventh day of the illness, unless otherwise indicated.

Acute fluid collection

This is a collection of fluid without a fibrous capsule occurring in the lesser sac in the first 6 weeks after the onset of pancreatitis. It is often asymptomatic, being diagnosed by a CT scan (Fig 4.13). It may be associated with slow resolution of the symptoms and signs of acute pancreatitis. It may resolve spontaneously or persist to develop a capsule, when it is defined as a pseudocyst. Alternatively, the collection may become infected, or produce gastric outlet obstruction, in which case it should be drained percutaneously under CT or ultrasound guidance. Otherwise, the collection should be monitored by serial CT or ultrasound scans.

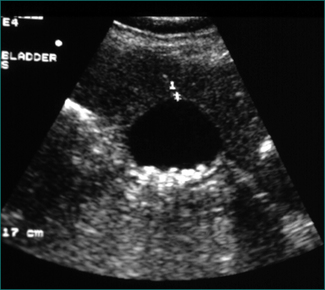

Pancreatic pseudocyst

This is an acute fluid collection that has developed a fibrous capsule over 6 or more weeks. It may be asymptomatic, or be associated with ongoing abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. It may be complicated by infection, haemorrhage or rupture. It may be evident as an abdominal mass (see Ch 19). If it is asymptomatic, it can be followed by serial scans (Fig 4.14). Smaller pseudocysts (under 5 cm) may resolve spontaneously; larger pseudocysts (over 5 cm) will persist and eventually need cyst-enteric drainage. Cyst-enteric drainage is also required for symptomatic pseudocysts (including infected pseudocysts). Cyst-enteric drainage involves draining the pseudocyst into the adjacent gastrointestinal tract lumen. This may be the stomach, duodenum or small bowel. The stomach and duodenum are used when the cyst abuts against these organs. The small bowel is used where the pseudocyst is distant from either the stomach or duodenal walls. Cyst-enteric drainage needs to be continued until the cavity of the collection shrivels. It can be performed percutaneously through the stomach under CT control, endoscopically through the posterior wall of the stomach, or transgastrically at laparoscopic or open operation. Where a pseudocyst cannot be drained into the stomach or adjacent duodenum an open operation is performed, and the pseudocyst joined to a loop of small bowel, in order to achieve cyst-enteric drainage.

Subsequent management

Attention should be directed towards prevention of further attacks of acute pancreatitis. This involves laparoscopic cholecystectomy and operative cholangiography for patients with gallstones. Only 25% of these cases are found to have persistent stones in the common bile duct (Fig 4.16), which can be removed intraoperatively by exploration of the common bile duct or postoperatively by ERCP. Abstinence from alcohol should be recommended for patients with alcohol abuse and the patient referred to a drug and alcohol specialist for ongoing management.

Severe acute pancreatitis with associated pancreatic necrosis may be complicated by the development of diabetes mellitus or malabsorption due to pancreatic endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, respectively (Ch 14).

Right Upper Quadrant Pain

Common causes of acute right upper quadrant pain are listed in Box 4.3.

Figure 4.15 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showing gallstones in the common bile duct.

Gallstones

Biliary pain (colic)

Biliary colic is severe pain of gradual onset, over 5–10 minutes, which reaches a peak that may be sustained for minutes to hours and then resolves slowly. It is more commonly experienced in the epigastrium than in the right upper quadrant, and may be in the lower chest and imitate an acute myocardial infarction type pain. The pain can be severe enough to cause agitation and a secondary tachycardia. It may radiate around the side to the right scapula or through to the back. The pain will often occur in the evening and may wake the patient from sleep. It can be associated with nausea and vomiting. If the patient has had the pain previously, gallstones may already have been demonstrated by upper abdominal ultrasound (Fig 4.16). As well as upper abdominal ultrasound, the following investigations are also performed:

Once the diagnosis of biliary colic is confirmed, initial management depends upon whether the pain is adequately controlled and whether the development of acute cholecystitis or evidence of stones in the common bile duct has complicated the attack of biliary colic. The complications of gallstones are listed in Box 4.4.

Acute cholecystitis

An attack of acute cholecystitis may settle within 24–48 hours. Recovery is assisted by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics administered parenterally. Resolution of the attack is associated with dislodgment of the obstructing gallstone from the gallbladder outlet. The diagnosis of cholecystitis is confirmed, if necessary, by demonstrating a thick-walled gallbladder on ultrasound.

Failure of acute cholecystitis to resolve leads to one of five complications:

Acute acalculous cholecystitis

This is a rare form of cholecystitis usually seen in the intensive care unit, where it occurs in debilitated patients, following major trauma, burns, recent major surgery or severe sepsis. Some of these patients are so unwell that they are unable to complain of right upper quadrant pain. If the patient complains of pain, diagnosis is by ultrasound. If there are no complaints of pain the diagnosis is made after clinical suspicion, with either ultrasound or CT scan. The alternative way of making a diagnosis is at surgery (when the clinical diagnosis has not been considered) performed as a result of unexplained deterioration thought to have an abdominal cause. Where the diagnosis is suspected and confirmed on ultrasound or CT scan, it may be managed with percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy and drainage of the gallbladder. When diagnosed at laparoscopy a cholecystostomy, rather than a cholecystectomy, may be required because of the patient’s poor physical state.

Definitive management of cholelithiasis

The definitive treatment of gallstones is cholecystectomy. If possible, the procedure is performed laparoscopically because this has a lower morbidity and more rapid recovery time than open cholecystectomy. Routine operative cholangiography is performed at the same time to ensure that unsuspected stones are not left behind in the common bile duct and that the common bile duct has not been injured during cholecystectomy. The risk of unsuspected choledocholithiasis at cholecystectomy is 3–7%. This possibility becomes more likely if one or more of the risk factors listed in Box 4.5 are present.

Acute right upper quadrant pain and jaundice

Most patients with both acute right upper quadrant pain and jaundice have a stone obstructing the common bile duct. If they have pain, jaundice and fever they have biliary obstruction with secondary infection or cholangitis. This triad of symptoms is known as Charcot’s triad (Ch 23). Initial management involves resuscitation and treatment of associated gram-negative sepsis. An urgent ultrasound examination should reveal cholelithiasis, a dilated common bile duct and sometimes a stone in the common bile duct. ERCP with sphincterotomy should be performed urgently if the signs of sepsis are severe, or early if they do not settle rapidly with parenteral antibiotics or the jaundice persists.

If the ultrasound examination does not demonstrate gallstones, other causes must be sought. In a small subset of patients, as discussed below, the explanation is apparent on the ultrasound of the liver. As mentioned above, normal serum amylase and lipase levels essentially eliminate unsuspected acute pancreatitis. Peptic ulceration is diagnosed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. For the remainder, no further investigation is required if the pain resolves without recurrence.

If the biliary colic recurs, the ultrasound examination should be repeated because small stones may be missed in up to 5% of cases. If the cause is still not apparent, a cholecystokinin-diethyl iminodiacetic acid (CCK-DIDA) test should be performed. This is a test of gallbladder function. Initially, DIDA is taken up by the liver, excreted in the bile and concentrated in the gallbladder. If the gallbladder is non-functional or contains tiny stones, it contracts minimally in response to cholecystokinin. If the cystic duct is obstructed by a small stone, the gallbladder will not be outlined (Ch 26).

Differential diagnosis of biliary colic

Occasionally, a patient with a clinical picture suggestive of acute biliary colic has an alternative explanation, which is apparent on ultrasound examination. More usually the pain is less severe in degree and more prolonged in duration. On review, there may be other clinical clues, which are summarised in Table 4.10.

Table 4.10 Causes of right upper quadrant pain other than gallstones found on ultrasound examination

| Diagnosis | Ultrasound findings | Clinical clues |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic metastases | Multiple solid lesions |

Hepatic metastasis

On ultrasound examination, usually multiple solid lesions are found throughout the liver. A CT scan is used to confirm the ultrasound findings and to assess the pancreas. Management of metastatic liver disease is covered in Chapter 26.

Hepatic abscess

In a patient with a hepatic abscess (Fig 4.18) the symptoms of sepsis (spiking fevers, night sweats, poor appetite and loss of weight) tend to overshadow the right upper quadrant pain.

Management of pyogenic abscesses has two components:

| Mechanism of infection | Examples |

|---|---|

| Cholangitis |

Hepatic adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia

The benign liver tumours, hepatic adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia, can cause right upper quadrant pain by intraperitoneal rupture, by bleeding into the lesion or expansion of the lesion. Their diagnosis is discussed in Chapter 26. Symptomatic and complicated lesions are usually managed by liver resection.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

As with hepatic adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma can cause right upper quadrant pain as a result of rupture, haemorrhage or expansion. The lesion usually arises in a cirrhotic liver, so that the patient may also have signs of chronic liver disease, portal hypertension or ascites. The diagnostic features on scanning are discussed in Chapter 26.

Hydatid cyst

This lesion may be asymptomatic or cause a dull ache in the right upper quadrant. It is caused by Echinococcus granulosus (rarely Echinococcus multilocularis). The appearance of the liver cyst on ultrasound examination is often diagnostic. In a living cyst, usually there are also daughter cysts. Calcification of the wall of the cyst indicates that the contents are no longer viable (Ch 26). The diagnosis is confirmed serologically, with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and a complement fixation test. Viable cysts need to be removed to prevent complications such as intraperitoneal rupture. Intraperitoneal spillage needs to be avoided during intraoperative clearance of the live cyst contents to avoid the risk of anaphylaxis and intraabdominal seeding with infective material. Preoperative therapy for several weeks with anthelmintics, such as albendazole, reduces the risk of recurrence.

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Hepatic vein thrombosis or Budd-Chiari syndrome that develops acutely is a rare cause of right upper quadrant pain. Ultrasound examination will show ascites and caudate lobe enlargement. The venous drainage of the caudate lobe is directly into the inferior vena cava, so that this segment hypertrophies as it is not affected by the hepatic vein thrombosis. CT scanning and Doppler flow studies are useful but liver biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Management is by treatment of the underlying cause (e.g. anticoagulation) and usually a portal systemic venous shunt (Ch 24).

Right upper quadrant pain after previous cholecystectomy

Recurrence of biliary pain after cholecystectomy occurs in 5–20% of patients. The cause may be due to a biliary or a non-biliary cause. Biliary causes include a retained or recurrent stone in the common bile duct or sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Non-biliary causes include peptic ulceration, pancreatitis, irritable bowel syndrome or non-ulcer (functional) dyspepsia.

Right Iliac Fossa Pain

The causes of right iliac fossa pain are listed in Box 4.6. Differentiation between the various causes is not always possible on clinical grounds, and investigations frequently do not help. Acute appendicitis remains largely a clinical diagnosis; CT scanning is useful where clinical uncertainty exists. Right iliac fossa pain seldom represents an intraabdominal catastrophe.

The initial aim of the clinician is to determine whether there is sufficient clinical evidence of localised peritonitis to require surgery. A patient with a typical history of periumbilical pain that shifts to the right iliac fossa, together with a low grade temperature, and localised and rebound tenderness maximal over McBurney’s point in the right iliac fossa, is likely to have acute appendicitis and should proceed to appendicectomy. Other signs of acute appendicitis are listed in Table 4.12. If the clinical picture is not clearly one of appendicitis, the next priority depends upon the gender of the patient. In women, consideration must be given to possible gynaecological causes of right iliac fossa pain (Box 4.6), some of which require surgical intervention. A history of abnormal or missed periods or a vaginal discharge is sought. A vaginal examination and speculum examination may demonstrate localised tenderness, a mass or a purulent discharge. Relevant investigations include a pregnancy test and pelvic ultrasound. Laparoscopy may be required to confirm a gynaecological diagnosis and/or deliver definitive treatment.

| Name | Sign |

|---|---|

| Jump tenderness | Jumping or hopping induces pain. Useful in children |

| Cough tenderness | Cough produces localised pain over McBurney’s point |

| Psoas sign | Pain on elevating right leg (due to inflammation adjacent to psoas muscle) |

| Rovsing’s sign | Tenderness felt in the right iliac fossa while palpating the left iliac fossa |

| Rectal tenderness | Tenderness palpable on the right side accentuated by bimanual palpation |

Specific management

Acute appendicitis

Terminal ileitis

Some patients with a clinical diagnosis of acute appendicitis are found to have terminal ileitis. Diarrhoea will have been a feature of the disease. The usual cause is Yersinia enterocolitica (Ch 13). This should be confirmed by convalescent serology. Occasionally, terminal ileitis that is not due to a bacterial cause is the first manifestation of Crohn’s disease.

Meckel’s diverticulum

A Meckel’s diverticulum is a congenital remnant of the vitelline duct. It is a true diverticulum that occurs on the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum, 45–60 cm from the ileocaecal sphincter. It occurs in 2% of the population and complications are unusual. If the base of the diverticulum is narrow, the diverticulum can become obstructed and present with an appendicitis-like illness. Other complications include:

These complications are managed by local resection of the diverticulum.

Left Iliac Fossa Pain

There are only a limited number of causes of acute left iliac fossa pain. They can be subdivided into gastrointestinal causes (Box 4.7) and the same non-gastrointestinal causes as right iliac fossa pain (Box 4.6).

Diverticular disease

Increasing age is associated with the development of pulsion diverticula of the colon. This process is associated with consumption of a diet low in roughage. Each diverticulum consists of a mucosal pouch with no external muscle. Diverticula are most commonly present in the sigmoid colon (Fig 4.19). They occur with decreasing frequency from sigmoid colon to caecum. They do not occur in the rectum, which has a complete outer longitudinal layer of muscularis propria. There may be hypertrophy of the muscularis propria of the sigmoid colon.

Uncomplicated diverticular disease is usually asymptomatic. Treatment of patients with diverticular disease with a long-term high-roughage diet reduces the incidence of the complications of diverticular disease. The infective complications of diverticular disease (acute diverticulitis, abscess, perforation and fistula formation) result when the neck of a diverticulum, which is narrower than the sac, becomes obstructed by faecal material and the contents of the sac become infected.

Complications of diverticular disease

The complications of diverticular disease include colovesical fistula, colovaginal fistula, coloenteric fistula, small bowel obstruction (discussed above under ‘Acute abdominal colic’), large bowel obstruction (discussed above under ‘Acute abdominal colic’) and gastrointestinal bleeding (see Ch 10).

Ischaemic colitis

The clinical presentation of ischaemic colitis may be similar to that of acute diverticulitis. Differentiating features include a history of cardiac disease, arrhythmia or other vascular disease, as well as a history of profuse bloody diarrhoea (Ch 10).

Key Points

Dang C., Aguilera P., Dang A., et al. Acute abdominal pain. Four classifications can guide assessment and management. Geriatrics. 2002;57:30-32. 35–36, 41–42

Korotinski S., Katz A., Malnick S.D. Chronic ischaemic bowel diseases in the aged—go with the flow. Age Ageing. 2005;34:10-16.

Mackay S., Dillane P. Biliary pain. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33:977-981.

Renzulli P., Jakob S.M., Tauber M., et al. Severe acute pancreatitis: case-oriented discussion of interdisciplinary management. Pancreatology. 2005;5:145-156.

Sajja S.B., Schein M. Early postoperative small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2004;91:683-691.

Stoker J., van Randen A., Lameris W., Boermeester M.A. Imaging patients with acute abdominal pain. Radiology. 2009;253:31-46.

Trowbridge R.L., Rutkowski N.K., Shojania K.G. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:80-86.

Wagner J.M., McKinney W.P., Carpenter J.L. Does this patient have appendicitis? J Am Med Assoc. 1996;276:1589-1594.

Werner J., Feuerbach S., Uhl W., et al. Management of acute pancreatitis: from surgery to interventional intensive care. Gut. 2005;54:426-436.