Acquired disorders of coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

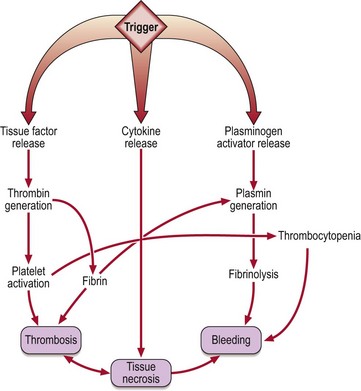

DIC is a complex clinical syndrome which complicates many serious illnesses (Table 38.1). It is characterised by intravascular deposition of fibrin and accelerated degradation of fibrin and fibrinogen caused by excess activity of proteases, notably thrombin and plasmin, in the blood (Fig 38.1). DIC is heterogeneous both in its pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. In most cases it probably begins when circulating blood is exposed to tissue factor released from damaged tissues, malignant cells or injured endothelium. This in turn leads to generation of thrombin which causes formation of soluble fibrin, activation of circulating platelets, and secondary fibrinolysis.

Table 38.1

DIC can cause bleeding, large vessel thrombosis and haemorrhagic tissue necrosis (Fig 38.2). The coagulation defect arises from consumption of coagulation factors and platelets and increased fibrinolytic activity. In clinical practice acute DIC usually presents as widespread bleeding in an ill patient. Oozing of blood from cannulation sites is characteristic. Microthrombus formation can lead to irreversible organ damage; the kidney, lungs and brain are frequent targets. DIC is not necessarily a fulminant syndrome; more chronic forms may be seen particularly in association with malignancy (e.g. prostatic carcinoma).

prothrombin time (PT) prolonged and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) usually prolonged

prothrombin time (PT) prolonged and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) usually prolonged

high levels of fibrin(ogen) degradation products (FDPs) and cross-linked fibrin degradation products (‘D-dimers’).

high levels of fibrin(ogen) degradation products (FDPs) and cross-linked fibrin degradation products (‘D-dimers’).

The cornerstone of management of DIC is the treatment of the underlying disease. Patients are more likely to die from this than from thrombosis or bleeding. However, specific treatment of DIC may be life-saving and if bleeding occurs support with blood products is indicated. Platelets, fresh frozen plasma (FFP – a source of coagulation factors) and cryoprecipitate (a source of fibrinogen) may all be used. Wherever possible the choice of blood products should be guided by the platelet count and coagulation tests. More controversial is the use of pharmacological inhibitors of coagulation and fibrinolysis. Although heparin can reduce clotting factor consumption and secondary fibrinolysis, it can also increase the haemorrhagic risk by its anticoagulant action. Its use should be considered where thrombosis predominates. Recombinant activated protein C may be beneficial in patients with severe sepsis and DIC.

Acquired haemophilia

Antibodies (‘inhibitors’) that block the action of coagulation factors may appear in patients who have no hereditary disorder of coagulation. Such autoantibodies most commonly target factor VIII and the clinical syndrome is termed ‘acquired haemophilia’. Acquired haemophilia may be associated with a number of conditions including rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune disorders, skin disorders, malignancy, drug therapy (particularly penicillin) and pregnancy. However, the most common presentation is in an elderly patient with no associated condition. Possible clinical problems include haemorrhage into soft tissues and muscles (Fig 38.3), haematuria, haematemesis and prolonged bleeding postpartum or postoperatively. Bleeding can be difficult to control and death occurs in approximately 10% of cases.

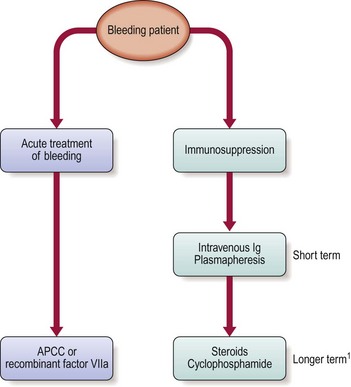

Management is complex and controversial but can be divided into the treatment of the acute bleeding episode and subsequent attempts to eliminate the autoantibody by immunosuppressive treatment. Possible approaches to the acute episode include activated prothrombin complex concentrate (such as FEIBA, which contains activated factors VII, IX, and X) and recombinant factor VIIa. Immunosuppressive strategies include intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis in the acute episode and longer-term steroids or cyclophosphamide. The usual approach is summarised in Figure 38.4.