6 Acquired brain injury

stroke, cerebral palsy and traumatic brain injury

Part 1 Stroke

Definition

A stroke is defined as a syndrome of rapidly developing clinical signs of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, with symptoms lasting 24 hours or longer, or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin [1]. The damage to the brain tissue is caused by thrombosis, embolus or haemorrhage. This leads to hemiplegia or some form of hemiparesis. The description of the stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) as ‘right’ or ‘left’ can be misleading as the resulting paralysis is usually on the side opposite to the brain lesion. This also assumes, incorrectly, that all the adverse effects will be unilateral.

Incidence

An estimated 150 000 people have a stroke in the UK each year, with over 67 000 deaths due to stroke, making stroke the most common cause of death in England and Wales after heart disease and cancer [2].

Stroke has a greater disability impact than any other disease, with many thousands of people living with moderate to severe disabilities as a result [3].

The direct cost of stroke to the NHS is estimated to be £2.8 billion and the cost to the wider economy is £1.8 billion. The informal care cost is around £2.4 billion, with the total costs of stroke predicted to rise in real terms by 30% between 1991 and 2010. Stroke patients occupy around 20% of all acute hospital beds and 25% of long-term beds [4].

It is thought that there has been an overall reduction in the numbers of strokes in the UK. Work undertaken in the Oxford region has shown that, as a result of the use of preventive medicines, including drugs that lower blood pressure and cholesterol and those that thin the blood, together with the reduction in heavy smoking, the incidence of stroke has dropped by 40% [5]. The current decline in incidence and case fatality may also be due to dietary changes and the emphasis on the treatment of hypertension [6]. There is a possibility that the predisposition to stroke runs in families, although this is likely to be linked to hypertension as the risk factor [7].

Mortality

Stroke is a devastating condition for both patients and carers, with a high mortality rate throughout the first year after the lesion: 30% at 3 weeks, 40% at 6 months and 50% at 1 year [8]. Morbidity is high, with 12% estimated to be in long-term care 1 year after the event [9]. The risk of recurrence is also high: 7% for at least 5 years after the initial stroke and 15 times the stroke risk for the general population [10]. The figures suggest that each health district can expect 550 patients to present with stroke each year and each general practitioner can expect to see four or five new cases a year and be caring for 12 survivors, of whom seven or eight will be disabled [11]. Stroke is therefore a major financial burden to the NHS and consumes more than 4% of total NHS expenditure and more than 7% of community health and social care resources [12].

Risk factors

There are many health factors which appear to predispose a patient to stroke. Age is the most important factor [13], but in general raised blood pressure [14], smoking [15] and alcohol consumption [16] are associated with a greater risk of occlusive and haemorrhagic stroke. Diabetes mellitus is associated only with occlusive stroke. Other factors that may be important are obesity, poor diet, febrile illness, oral contraception, taking hormone replacement therapy and, in some cases, wide seasonal variation in temperature, although this can be either extreme cold or heat [17]. It has also been suggested that the seasonal availability of vitamin C may be a factor [18], although with the wide variety of non-seasonal foods now available this may not be an issue in industrial nations.

Diagnosis

Differentiation from other diseases

Transient ischaemic attack

TIA is defined as a ‘clinical syndrome characterized by acute loss of cerebral or monocular function with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours’. These patients are often unaware of what has happened to them and unlikely to present for treatment; however they do retain a heightened risk of stroke and if discovered should be seen by a primary care doctor for preventive treatment [19]. TIA is not described as a true stroke.

(Acupuncture may have some thing to offer at this stage; see the syndrome ‘Rising Liver Fire’, linked to Kidney Yin Xu, in Chapter 1. Treatment is aimed at prophylaxis, including the lowering of blood pressure.)

Clinical stroke syndromes

It is relatively easy to distinguish vascular strokes – those caused by emboli, haemorrhages and infarcts – from non-vascular pathology. However, up to 13% of patients thought initially to have had a vascular stroke turn out to be suffering from other pathology [20, 21]. Stroke is most commonly confused with epilepsy, delirium and loss of consciousness, tumours, depression and dementia syndromes.

Dementia manifests as a global impairment of higher mental function, without loss of consciousness. Multiple cerebral infarcts are the predominant pathology in 10–30% of patients and as many again have mixed pathology with vascular signs. The site of the infarction may generally be more important than the absolute volume of brain tissue lost. Cardiac embolism is likely to be an important factor but is of unknown incidence and difficult to diagnose with certainty [6].

Stroke can be divided into four subgroups with distinctive clinical characteristics. The following definitions are taken from Stroke: Epidemiology, Evidence and Clinical Practice [6, 22].

Total anterior circulation infarct (TACI)

This group has a poor chance of good functional outcome and mortality is high.

Partial anterior circulation infarcts (PACIs)

This group of patients is more likely to have a second stroke in the first year.

Silent infarcts

Prevalence of silent infarction increases with age and the risk factors are no different from those for symptomatic stroke. The increased likelihood of cognitive impairment among subjects reporting stroke symptoms in the absence of a diagnosed stroke or TIA suggests that such symptoms are not benign and may warrant clinical evaluation that includes cognitive assessment [23].

Medical treatment

Acute

A welcome innovation has been a widespread advertising campaign to alert the public to the first signs of stroke [24], emphasizing that stroke should be recognized as a medical emergency requiring fast admission and specialist management. Patients who have suffered a stroke remain at increased risk of a further incident: therefore secondary prevention is part of treatment.

The International Stroke Trial investigated 19 435 patients within 48 hours of acute stroke and randomized them between two different doses of heparin or placebo [25]. The design also randomized patients to receive daily aspirin or no aspirin. The researchers used a 2×2 factorial design with patients randomized to one of four possible groups: heparin and aspirin, aspirin or heparin alone or no treatment. Treatment lasted 14 days or until discharge, if sooner.

The other major study, the Chinese Acute Stroke Trial [26], randomized 20 000 patients to daily low-dose aspirin or a placebo, also within 48 hours of the stroke. Treatment lasted 4 weeks. The Chinese Acute Stroke Trial study showed that aspirin started in the acute stage was associated with small benefits. The difference in death rates between the aspirin and control groups was only 0.5%. Combining the data from these two very large trials detects a small treatment effect for aspirin, thus supporting the early prescribing of aspirin, as long as continuing haemorrhage has been excluded. As aspirin is prescribed in any case for long-term prevention it becomes imperative that CT scans take place routinely very soon after stroke.

Thrombolytic drugs have also been investigated, particularly tissue plasminogen activator (tPA, alteplase) given within just 3 hours of an acute ischaemic stroke. The most recent Cochrane review [27] balances the increase in deaths within the first to seventh days and deaths at final follow-up with the reduction in disability in the survivors. It suggests that intravenous recombinant tPA may be the best method of delivery but is cautious about recommending general use.

However the current advice given to physicians [28] is that thrombolytics may be given but haemorrhage must definitely be excluded and that the patient should be in a specialist centre with appropriate experience and expertise.

Subacute

Spasticity is a motor disorder characterized by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes. It commonly leads to muscle shortening and joint contractures. Signs of change in muscle tone are observable within a few days of the initial brain damage. A relatively new drug used to combat spasticity is botulinum toxin (BTX or BoNT). A number of trials among stroke patients have shown a significant decrease in muscle tone. The effects of the BTX were shown to decrease after 3 months, but if the patients were regaining control of their muscles, that could be seen as an advantage. Several studies have shown a good effect in stroke rehabilitation situations [29–31]. The trial by Lai et al. [31] shows that an increased effect is gained by serial splinting to maintain the increase in range of movement gained by the relaxing muscle spasm. It would be interesting to compare that with the muscle-relaxing effect of acupuncture, either in place of, or used with, BTX.

Management and rehabilitation

Correct positioning of stroke patients is a widely advocated strategy to prevent the development of abnormal muscle tone, contractures, pain, skin breakdown and respiratory complications. Since this and the other supportive treatments require a constant team effort, it has been demonstrated that patients in specialist stroke units are likely to do better [32].

Prognosis

Body structure and function, activity and participation

The effect of stroke, or indeed any neurological condition, is described in varying ways. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) suggests that an individual’s disability and resultant function is a result of the interactions between his or her health condition and contextual factors such as the physical environment or social attitudes [33]. A full description is included in this chapter, although it applies equally to the others.

ICF highlights the relationship between problems with body structure and function and the individual’s level of activity and participation (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Definitions of major International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health categories

| Category | World Health Organization definition (33) |

|---|---|

| Body structure | Anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs and their components |

| Body function | Physiological functions of body systems, including psychological functions |

| Activity | The execution of a task or action by an individual |

| Participation | Involvement in a life situation |

Effects of stroke

Depending on the site of the lesion there may be varying degrees of speech loss or swallowing difficulties and there is a real danger of food aspiration in the acute stage of stroke. Most patients with moderate to severe stroke are incontinent at admission, and many are discharged still incontinent. Both urinary and faecal incontinence are common in the early stages and need urgent management in order to prevent these problems delaying the patients’ eventual rehabilitation. Urinary incontinence directly after stroke is an indicator of poor prognosis for both survival and functional recovery [34]. Care must be taken to prevent infection.

Anxiety is an equally common problem accompanied by feelings of fear and apprehension with physical symptoms such as breathlessness, palpitations and trembling. The specific causes of anxiety after stroke are not known; it may simply be a product of the sudden physical disability or may more closely resemble an anxiety disorder and require antidepressive drug treatment. Anxiety after stroke has certainly been shown to be associated with increased severity of depressive symptoms and greater functional impairment [35].

Long periods of inactivity produce a danger of skin breakdown and the possibility of pressure sores is increased if the patient is also incontinent. The lack of voluntary movement also increases the risk of deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus. Early mobilization after stroke has been shown both to cut rates of poststroke depression by 50% and also to be cost-effective [36, 37]. This has implications for early acupuncture treatment of this condition. The link between exercise and general feeling of well-being and mood elevation is well documented in healthy subjects [38], and the chemical action of acupuncture has often been compared to that of exercise [39].

A further complication of recovery is spastic hypertonia associated with exaggerated deep tendon reflexes. This is often associated with central nervous system disorders due to lesions in the brain that affect descending tracts normally inhibiting spinal reflex pathways. The resulting excessive muscle tone can cause many problems, including loss of free movement, difficulties performing daily activities and pain [40]. It may also cause the limb to become ‘frozen’ or fixed in an uncomfortable position.

Pain is most common in the affected shoulder. It is to be hoped that it is less often present now that much emphasis is placed on correct positioning of the paralysed limbs [41]. Unfortunately the initial loss of muscle tone in the hemiplegic arm often results in damage to the capsule with subsequent pain. Use of functional electrical stimulation can help prevent this unpleasant complication [42].

Patterns of recovery

The aim of all treatment should be independence in self-care within a year after the stroke. This is achieved in a range between 60% [43] and 83% [44] of surviving patients, both measured at 1 year after stroke. However the same data suggest that between 16 and 31% may be institutionalized by the end of the year.

Recovery of rolling, sitting balance, transfers and walking among patients referred for rehabilitation seems to follow a relatively predictable pattern over the first 8 weeks [45]. The majority of muscle recovery occurs within the first 3 months after the stroke with subsequent recovery taking place at a slower pace [46]. Some useful recovery still occurs between the sixth and twelfth months. In the hemiplegic hand it is thought that if there is no active hand grip after 3 weeks there is unlikely to be much improvement [47].

The accepted wisdom within the physiotherapy profession is that there is little to be gained from the rehabilitation process as late as 2 years after the stroke, but there may be unused potential for physical improvement in the period before this cut-off, depending on previous access to treatment. Overall recovery is thought to be adversely affected by the patients’ age [48]. This assumes that there may be co-pathology, including mobility problems such as osteoarthritis.

Recurrence

One in five strokes is a recurrent stroke and a patient who has had one stroke is at 10-fold increased risk of another [49]. Despite similar neurological impairments, patients with recurrence on the opposite side to their original episode tend to have markedly more severe functional disability after completed rehabilitation than patients with an ipsilateral recurrence, implying that functional ability to compensate is decreased. These figures serve to underline the importance of a prophylactic dose of aspirin or even acupuncture.

Stroke and physiotherapy

Current physiotherapy

The modalities used by the physiotherapist are many and varied, based essentially on the retraining of physical movement and incorporating forms of biofeedback to retrain balance and proprioception [50], functional electrical stimulation [51], gait retraining and treadmill training [52]. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has also been used successfully [53], usually utilizing acupuncture points. Approaches to treatment vary but may also include techniques drawn from the Bobath approach, movement science and, on occasion, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. Research has failed to identify substantial differences between the different approaches but a clear finding is the need for intensive training [54]. More research on the individual components of rehabilitation is still required.

Spontaneous neurological recovery is considered by many to be responsible for most of the functional recovery after stroke but in a critical review Kwakkel et al. suggested that simple biological variability may encourage rehabilitation-induced effects and that comprehensive functional therapy incorporating elements of intensive and task-specific strategies may ultimately produce the best effects [55].

Application of acupuncture

Prevention of stroke by traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) acupuncture depends on meticulous TCM diagnosis and is both complicated and unproven, but the type of acupuncture applied after stroke to combat the paralysis is not complex and is well within the capacity of any physiotherapist with basic acupuncture training. The state of current research is confused but indicates possible applications [56].

Neurological basis

The specific neurological changes that could benefit a stroke patient are described in detail in Chapter 4. However the demonstrable physiological effects of acupuncture in stroke are as follows.

Changes in cerebral circulation

Given the pathology of stroke, it is clear that an acupuncture intervention that could maintain peripheral circulation to the cerebral hemispheres when the central supply is compromised would be useful acute therapy [57].

Changes in blood composition, velocity and general circulation

Changes in blood flow and velocity, noted by Yuan et al. [57] and Litscher et al. [58], could be helpful in preventing further emboli and aiding with reperfusion of temporarily damaged brain tissue. Indeed, these changes may mirror the actions of tPA or aspirin and could be considered as an alternative if the acupuncture could be administered quickly enough.

Effects on muscle tissue

A general increase in blood flow could be beneficial to recovering muscle tissue, particularly that which has been damaged by long-term disuse. One of the main perceived problems with rehabilitation is the increase in muscle tone and acupuncture has been shown to have a potentially useful decreasing effect [55, 59, 60]. In a good-quality trial, but with small numbers, clinically relevant changes in spasticity were observed to be comparable to those produced by botulinum toxin injections [61].

More work is needed on this aspect of acupuncture and stroke. A more general effect on muscle tissue, leading to an increase in muscle strength in healthy subjects, has been demonstrated, although only in small studies [62, 63]. In a larger study carried out in the UK, the Motricity Index was used to measure muscle strength recovery in stroke patients and the researchers found that acupuncture appeared to produce a boost for this in the early stages of recovery [64].

The use of electroacupuncture raises a further set of questions for the researcher but does seem to be effective in some situations, for example in poststroke shoulder subluxation, where electroacupuncture has been shown to have a useful effect if applied in the early stages [65] (Figure 6.1).

Using electroacupuncture, Shen et al. [66] showed that the combination of electroacupuncture and exercise therapy improved limb function in the hemiplegic patient, and, additionally, that the therapeutic effect of exercise was increased if it was given after the acupuncture.

A paper in Chinese suggests that scalp acupuncture, a form of electroacupuncture, (see Chapter 12: Figure 6.2), works better if used in combination with exercise therapy in stroke rehabilitation [67].

Effects on mood

Acupuncture is associated with improvements in mood and energy, due in part to the observed increase in serotonin and endorphins. This evidence has been around for some time [68] but the positive psychological effects are coming under closer scrutiny now [69]. Since it has been suggested that depression and anxiety after stroke are associated with increased severity of depressive symptoms and greater functional impairment [35], this alternative to drug therapy may be very acceptable and will assist with patient compliance with taxing exercise programmes [70].

Effects on energy levels

There is a lot of anecdotal evidence linking acupuncture with an increase in energy level but little hard research, particularly in the field of neurology. However, an interesting study by Molassiotis et al., working with oncology patients, showed a significant decrease in fatigue after the application of acupuncture [71]. Given the known effect of the acupuncture stimulus on the limbic system it is not unreasonable to assume that this would be the case. A similar effect was detected in the Hopwood trial of acupuncture in stroke patients with just subsignificant results on the Nottingham Health Profile scale for emotional reaction and energy levels, in favour of the acupuncture group at 24 weeks after their stroke [64].

A Canadian project to create guidelines for 13 types of physical rehabilitation interventions used in the management of adult patients (>18 years of age) presenting with hemiplegia or hemiparesis following a single clinically identifiable ischaemic or haemorrhagic CVA was developed in 2006 [72]. This group identified and synthesized evidence from comparative controlled trials. The group then formed an expert panel which developed a set of criteria for grading the strength of the evidence and the recommendation. Patient-important outcomes were determined through consensus, provided that these outcomes were assessed with a valid and reliable outcome scale.

The Ottawa Panel developed 147 positive recommendations of clinical benefit concerning the use of different types of physical rehabilitation interventions involved after stroke. Among those listed were therapeutic exercise, task-oriented training, biofeedback, gait training, balance training, treatment of shoulder subluxation, electrical stimulation, TENS, therapeutic ultrasound and acupuncture [72].

Table 6.2 offers a summary of the symptoms that are likely to be present to a greater or lesser degree in most stroke patients. Obviously one of the characteristics is the unilateral nature of the impairment but otherwise these symptoms are common throughout this group of neurological conditions.

| Symptom | Characteristic presentation | Stroke |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased mobility | Hemiparesis or hemiplegia |   |

| Fatigue | Lack of energy |  |

| Respiratory problems | Weak cough | X |

| Muscle spasm | Increased tone |   |

| Contractures | Stiffness and rigidity leading to deformity |  |

| Autonomic changes | Slowing circulation |  |

| Cognition/mood | Emotional lability, poststroke depression |  |

| Communication | Sometimes hampered by facial palsy (loss of speech with right cerebrovascular accident) |   |

| Bladder problems | Occasional | X |

| Visual problems | Hemianopia, single-sided visual neglect |  |

X, usually absent;  , common,

, common,

, very frequent.

, very frequent.

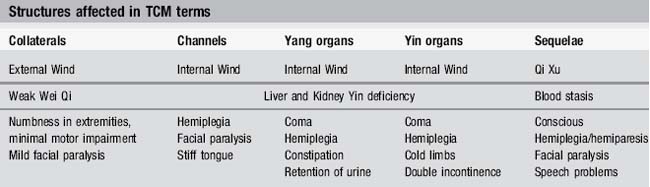

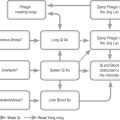

Links to TCM

TCM recognized the effects of stroke and categorized the symptoms over 2000 years ago (Table 6.3). Before the Tang and Song dynasties, the pathomechanism of stroke was seen as the result of some internal deficiency followed by a Pathogenic attack. Later the condition was considered to be primarily a result of internal Wind. Contemporary Chinese TCM doctors now view this disease as deficiency of upright Qi leading to an internal stirring of Liver Wind. Onset is also related to disorders involving the Yin and Yang of the Heart and Liver, Spleen and Kidney, in their Zang Fu sense.

The risk factors of diet, obesity, high blood pressure and a sedentary occupation have been acknowledged in the sizeable literature dealing with stroke treatment using both herbs and acupuncture [73–75]. The very fact that this type of treatment has been reported as clinically successful for so long underlines the need for more rigorous research in this field.

Simple acupuncture formula for windstroke sequelae

Upper-limb points

GB 20 Fengchi, LI 15 Jianyu, LI 11 Quchi, LI 10 Shousanli, LI 4 Hegu, TE 5 Waiguan.

Lower-limb points

Some authorities recommend the use of points on the unaffected limb, some use them bilaterally but there seems to be no clear guide as to which is better. From the point of view of a stimulus to the nervous system to prevent stroke-side neglect, it seems logical to treat only the affected side. It also seems logical to add electroacupuncture using a current of 2 Hz in order to produce a muscle twitch. However bilateral treatment makes sense too; stimulation of both dorsal horns will maximize the effect. TCM sometimes advises starting with the unaffected side and progressing to both sides [76].

The TCM differentiation of stroke offers four patterns, similar to those in the West:

It is the Zhong Jing type that is most likely to be treated by physiotherapists and, if the Zhong Fu and Zhong Zang survive they will show the same one-sided paralysis of the limbs and sometimes the face [77].

The fundamental causative factors are thought to be linked to the Wei and Feng syndromes (see Chapter 1).

Syndromes identified in stroke

As with most neurological conditions the state or balance of all the body system is seen to be disturbed and the following syndromes are often found within the umbrella classification of ‘poststroke’. Table 6.4 offers collections of acupoints which can be used if the symptoms fit.

| Syndrome | Main points | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Attack on the channels with external Pathogens still retained in the body |

Acupuncture is rarely used in isolation in TCM. Specific Chinese herbal medicine will also be prescribed to invigorate blood and transform stasis. Table 6.5 offers a more eclectic selection of points, mostly chosen on the basis of myotomes and muscle innervation or useful Yang meridians.

Table 6.5 Acupuncture points used in stroke

| Problem | Acupoints | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Paralysis of the extensor groups of the Upper Limb (Yang aspect) | Chinese texts also suggest LI 17 Tianding but this is awkward to needle and most relevant with loss of voice | |

| Paralysis of the flexor groups of the Upper Limb (Yin aspect) | ||

| Paralysis of the Lower Limb (Yang aspect) | GB 31 also useful | |

| Paralysis of the Lower Limb (Yin aspect) | SP 9 if oedema present | |

| Shoulder pain | Support subluxation | |

| Facial paralysis, deviation of the mouth | Also used in Bell’s palsy | |

| Deviation of the tongue and aphasia | ||

| General trunk weakness and asymmetry | Could also open Du meridian with SI3 Houxi and BL 62 Shenmai | |

| Internal problems including loss of appetite, constipation difficulties with urination | Sp 6 Sanyinjiao also helpful | |

| To eliminate pathogenic Wind | GV 20 Baihui and GV 16 Fengfu may also be used |

Summary

Relatively weak but cumulative evidence from the recent research literature indicates that investigation of the effect of acupuncture on both motor power and spasticity is not yet complete [56, 61, 64, 78–80]. Although the evidence for acupuncture in acute stroke remains equivocal, the borderline trends in the Cochrane review [81] indicate further work on two aspects, motor recovery and overall morbidity, with perhaps more accurate distinction between haemorrhagic and non-haemorrhagic stroke.

Case studies

Case study 6.2: level 2 case study

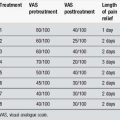

Acupuncture treatment

Points: first treatment: LI 11, LI 10, LI 4 and Baxie 15 minutes. Deqi was felt at all points.

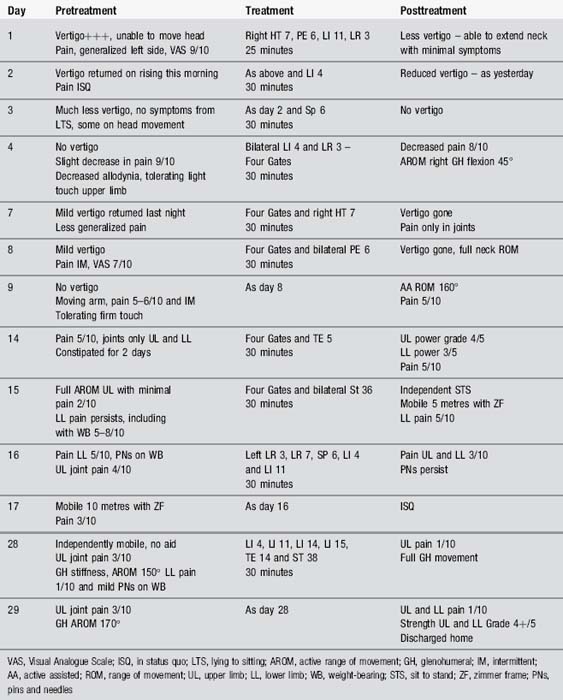

Case study 6.3: level 3 case study

Treatment

Acupuncture was suggested as his pain and vertigo were preventing him from attending other therapy sessions (Table 6.6).

Comment

Centrally generated or central neuropathic pain results from damage to the central nervous system. Central poststroke pain (CPSP) is estimated to occur in up to 8% of patients following a stroke and can begin up to a month after the event [82]. It is thought that damage to the spinothalamic pathways is responsible for this pain. The most common treatment for CPSP is the use of amitriptyline, which is also commonly used as an antidepressant. This was prescribed early on in the patient’s management. However, it seemed to be of no benefit. Gabapentin, another neuropathic painkiller, was subsequently prescribed but made the patient very drowsy and he chose to cease taking it.

Conclusion

Although CPSP is one of the less common sequelae of stroke, it can be incredibly debilitating for those who experience it and is notoriously difficult to manage. Pharmaceutical management is often inadequate and can be associated with unpleasant side-effects. The outcome of this case study supports that of Yen and Chen [83], that the use of acupuncture alongside standard Western rehabilitation can be effective in the management of CPSP. Further investigation into the use of acupuncture for the management of this kind of neuropathic pain would be of great interest.

Part 2 Cerebral palsy

Acupuncture

The focus of acupuncture treatment will be very similar to that for stroke.

The effect of the treatment was measured by evaluating the children’s performance of physical exercise, social adaptability and their intelligence quotient (IQ) both before and after the treatment period. The results revealed ‘a very positive improvement in the children’s physical capability and an increase of their intelligence’ [84].

A clinical study of acupuncture looking at both the Bobath approach, commonly used by physiotherapists, and acupuncture was undertaken in 2005 [85]. This involved the treatment of 90 cases of spasmodic cerebral palsy patients aged from 1 to 10 years. The patients were randomly divided into three groups, with 30 members in each group: group A (acupuncture group), group B (rehabilitation training group) and group C (acupuncture and rehabilitation training group).

In a similar study, again with a mixture of exercise, Bobath techniques and acupuncture, Mu et al. [86] suggest that the combination of techniques can be effective. More recently a single case study [87] seemed to indicate that in the child studied a simple acupuncture intervention, regular needling of GB 34 and St 36, resulted in temporary cessation of involuntary extension contractions of the erector spinae muscle. This was not maintained between treatments. Although of limited value evidentially this case indicates that there may be a response worth full investigation in the future.

Acupressure as a single intervention has been recommended for cerebral palsy but this has little evidence base and seems to need to be undertaken regularly over a very long period [87]. Many of the acupressure points offered as useful for general mobilization of the soft tissues in cerebral palsy patients correspond clearly with trigger points known to Western medical acupuncture [88]. A form of light massage given regularly to areas of muscle with perceived physiological changes can be helpful in decreasing muscle tone; this type of massage is sometimes termed Tuina.

Part 3 Traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury is a form of acquired brain injury resulting from sudden trauma to the brain. This injury is commonly caused by road traffic accidents, but may also result from falls, assault, gunshot wounds and sporting injuries [89]. The brain may be damaged by accelerating, decelerating and impacting on the inside of the skull leading to bleeding, bruising and damage to nerve cells and fibres. The skull may remain intact or may be fractured [90]. Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide, causing up to 1.5 million deaths annually. It causes severe disability for 150–200 people per million each year and is the leading cause of disability for those aged under 40 years [91]. Injuries are more common in people aged 15–24 or over 75 years [92].

Prognosis

Outcome following traumatic brain injury depends on the severity of initial damage. Improvement in acute management means that some of those with severe injuries will now survive. These individuals are likely to develop substantial disability and require long-term support. Those with less severe injuries may be left with minor or moderate residual symptoms. However some of those with apparently minor injuries may experience long-lasting difficulties which have a substantial impact on their functional ability and participation within the wider community [92].

Traumatic brain injury and acupuncture

The focus of acupuncture shares similarities with the approach to stroke and includes the use of Yang meridians in the upper and lower limbs. However, the sudden and traumatic onset of injury may result in areas of local Qi or Blood stagnation as well as the effect of shock on the Heart and Kidney, causing depletion [75]. Common TCM patterns noted in traumatic brain injury include blood stasis, hyperactivity of Liver Yang, obstruction of Phlegm, deficiency of Kidney Essence and deficiency of Qi and Blood [93].

Very little research has been conducted in this condition. A Chinese study by He et al. [94] reported the use of acupuncture in 30 cases of posttraumatic coma. Patients in the treatment group (n = 15) received acupuncture and point injection in addition to standard care. This study reported that patients in the acupuncture group showed ‘obvious’ improvement in symptoms such as aphasia, hemiplegia, facial weakness and eye movement in comparison to the control group. These are interesting results but studies with more rigorous design and outcome measurements are required. A number of case reports have noted benefits from acupuncture in traumatic brain injury. Chen used needling of Shendao (GV 11) complemented by Guanyuan (CV 4) to improve circulation through the Governor and Conception Vessels [93]. He reported greater benefits from this option for relief of spasticity than from body, scalp or ear acupuncture. Donnellan reported benefits from body acupuncture for the relief of central neuropathic pain and mood disturbance in a patient with severe traumatic brain injury and multiple fractures [95].

[1] World Health Organization WHO. Cerebrovascular Disorders. Geneva: Offset publications, 1978.

[2] Peterson S., Peto V., Scarborough P., et al. Coronary Heart Disease Statistics. London: British Heart Foundation, 2005.

[3] Adamson J., Beswick A., Ebrahim S. Is stroke the most common cause of disability? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;13(4):171-177.

[4] National Audit Office U. Reducing brain damage: faster access to better stroke care. London: The Stationery Office, 2005.

[5] Goldacre M.J., Duncan M., Griffith M., et al. Mortality rates for stroke in England from 1979 to 2004: trends, diagnostic precision, and artifacts. Stroke. 2008;39(8):2197-2203.

[6] Ebrahim S., Harwood R. Stroke: Epidemiology, evidence and clinical practice, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

[7] Wannamethee S.G., Shaper A.G., Ebrahim S. History of parental death from stroke or heart trouble and the risk of stroke in middle-aged men. Stroke. 1996;27:1492-1498.

[8] Wade D.T. Stroke (acute cerebrovascular disease). In: Stevens A.R.J., editor. Health care needs assessment: the epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1994:111-255.

[9] Legh-Smith J., Wade D.T., Langton-Hewer R. Services for stroke patients one year after stroke. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986;40:161-165.

[10] Burn J., Dennis M., Bamford J. Long-term risk of recurrent sstroke after a first- ever stroke. Stroke. 1994;25:333-337.

[11] Wade D.T., Langton Hewer R. Epidemiology of some neurological diseases with special reference to work load on the NHS. Int Rehabil Med. 1987;8(3):129-137.

[12] Department of Health. Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. London: Stationery Office, 1999.

[13] Balarajan R. Ethnic differences in mortality from ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease in England and Wales. BMJ. 1991;302:560-564.

[14] Juvela S., Hillbom M., Palomaki H. Risk factors for spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Stroke. 1995;26:1558-1564.

[15] Robbins A.S., Manson J.E., Lee I.M., et al. Cigarette smoking and stroke in a cohort of US male physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:458-462.

[16] Gill J.S., Zezulka A.V., Shipley M.J., et al. Stroke and alcohol consumption. N Engl J Med.. 1986;315:1041-1046.

[17] Christie D. Stroke in Melbourne, Australia: an epidemiological study. Stroke. 1981;12:467.

[18] Bulpitt C.J. Vitamin C and vascular disease. Br Med J. 1995;310:1548-1549.

[19] Kirshner H.S. Prevention of secondary stroke and transient ischaemic attack with antiplatelet therapy: the role of the primary care physician. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(10):1739-1748.

[20] Norris J.W., Hachinski V.C. Misdiagnosis of stroke. Lancet. 1982;i:328-331.

[21] Libman R.B., Wirkowski E., Alvir J., et al. Conditions that mimic stroke in the emergency department: implications for acute stroke trials. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:1119-1122.

[22] Bamford J., Sandercock P., Dennis M., et al. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991;337(8756):1521-1526.

[23] Wadley V.G., McClure L.A., Howard V.J., et al. Cognitive status, stroke symptom reports, and modifiable risk factors among individuals with no diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Stroke. 2007;38(4):1143-1147.

[24] The Stroke Association. Stroke is a Medical Emergency. UK. Northampton: The Stroke Association, 2008.

[25] IST. The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349:1569-1581.

[26] Chinese Acute Stroke Trial. CAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20 000 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Chinese Acute Stroke Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349(9066):1641-1649.

[27] Wardlaw J.M., del Zoppo G., Yamaguchi T. Thrombolysis for acyute ischaemic stroke (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library. (3):2002.

[28] Intercollegiate Working Party. Care after Stroke or Transient Ischaemic attack. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. Clinical Standards

[29] Ashford S., Turner-Stokes L. Management of shoulder and proximal upper limb spasticity using botulinum toxin and concurrent therapy interventions: A preliminary analysis of goals and outcomes. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2009;31(3):220-226.

[30] Elovic E.P., Brashear A., Kaelin D., et al. Repeated treatments with botulinum toxin type a produce sustained decreases in the limitations associated with focal upper-limb poststroke spasticity for caregivers and patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(5):799-806.

[31] Lai J.M., Francisco G.E., Willis F.B. Dynamic splinting after treatment with botulinum toxin type-A: A randomized controlled pilot study. Adv Ther. 2009;26(2):241-248.

[32] Ottenbacher K.J., Jannell S. The results of clinical trials in stroke rehabilitation research. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:37.

[33] World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002.

[34] Patel M., Coshall C., Lawrence E., et al. Recovery from poststroke urinary incontinence: associated factors and impact on outcome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(9):1229-1233.

[35] Schultz S., Castillo C., Kosner J., et al. Generalised anxiety and depression: assessment over 2 years after stroke. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5:229-237.

[36] Bernhardt J., Dewey H., Thrift A., et al. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39(2):390-396.

[37] Tay-Teo K., Moodie M., Bernhardt J., et al. Economic evaluation alongside a phase II, multi-centre, randomised controlled trial of very early rehabilitation after stroke (AVERT). Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26(5):475-481.

[38] Jones M., O’Beney C. Promoting mental health through physical activity: examples from practice. Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2004;3(1):39-47.

[39] Andersson S. Physiological mechanisms in acupuncture. In: Hopwood V., Lovesey M., Mokone S., editors. Acupuncture and Related Techniques in Physiotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:19-39.

[40] Bakheit A.M.O., Thilmann A.F., Ward A.B., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study to compare the efficacy and safety of three doses of botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) with placebo in upper limb spasticity after stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(10):2402-2406.

[41] Braus D.F., Kraus J.K., Strobel J. The shoulder–hand syndrome after stroke: a prospective clinical trial. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:728-733.

[42] Chantraine A., Baribeault A., Uebelhart D., et al. Shoulder pain and dysfunction in hemiplegia: effects of functional electricaal stimulation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;3:328-331.

[43] Aho K., Harmsen P., Hatano S., et al. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58(1):113-130.

[44] Skilbeck C.E., Wade D.T., Hewer R.L., et al. Recovery after stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1983;46:5-8.

[45] Partridge C.J., Johnston M., Edwards S. Recovery from physical disability after stroke: normal patterns as a basis for evaluation. Lancet. 1987;i:373-375.

[46] Wade D.T., Langton Hewer R. Functional abilities after stroke: measurement, natural history and prognosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;52:1267-1272.

[47] Humphrey P. Stroke and transient ischaemic attacks. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:534-543.

[48] Barer D.H., Mitchell J.R. Predicting the outcome of acute stroke: do multivariate models help? Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 1989;70:27-39.

[49] Jorgensen H.S., Nakayama H., Reith J., et al. Stroke recurrence: predictors, severity, and prognosis. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Neurology. 1997;48:891-895.

[50] Dursun E., Hamamci N., Donmez S. Angular biofeedback device for sitting balance of stroke. Stroke. 1996;26:1354-1357.

[51] Glanz M., Klawansky S., Stason W., et al. Functional electrostimulation in post-stroke rehabilitation: a meta-analysis of the randomised, controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:549-553.

[52] Visintin M., Barbeau H., Korner-Bitensky N., et al. A new approach to retrain gait in stroke patients through body weight support and treadmill stimulation. Stroke. 1998;29:1122-1128.

[53] Tekeoolu Y., Adak B., Goksoy T. Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) index score following stroke. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12:277-280.

[54] Kwakkel G. Impact of intensity of practice after stroke: Issues for consideration. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(13/14):823-830.

[55] Kwakkel G., Wagenaar C., Twisk J., et al. Intensity of leg and arm training after primary middle cerebral artery stroke: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:191-196.

[56] Mukherjee M., McPeak L.K., Redford J.B., et al. The effect of electro-acupuncture on spasticity of the wrist joint in chronic stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(2):159-166.

[57] Yuan X., Hao X., Lai Z., et al. Effects of acupuncture at Fengchi point (GB 20) on cerebral blood flow. J. Tradit. Chin Med. 1998;18(2):102-105.

[58] Litscher G., Schwarz G., Sandner-Kiesling A., et al. Effects of acupuncture on the oxygenation of cerebral tissue. Neurol Res. 1998;20(Suppl. 1):528-532.

[59] Yu Y., Wang H., Wang Z. The effect of acupuncture on spinal motor neuron excitability in stroke patients. Chin Med J (Taipei). 1995;56:258-263.

[60] Zhao Z.Q. Neural mechanisms underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;85:335-375.

[61] Wayne P.M., Krebs D.E., Macklin E.A., et al. Acupuncture for upper-extremity rehabilitation in chronic stroke: a randomised sham-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12):2248-2255.

[62] Ludwig M. Influence of acupuncture on the performance of the quadriceps muscle. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Akupunktur. 2000;43(2):104-107.

[63] Huang L., Zhou S., Lu Z., et al. Bilateral effect of unilateral electroacupuncture on muscle strength. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(5):539-546.

[64] Hopwood V., Lewith G., Prescott P., et al. Evaluating the efficacy of acupuncture in defined aspects of stroke recovery: a randomised, placebo controlled single blind study. J Neurol. 2008;255(6):858-866.

[65] Ada L., Foongchomcheay A. Efficacy of electrical stimulation in preventing or reducing subluxation of the shoulder after stroke: a meta-analysis. Aust J Physiother. 2002;48(4):257-267.

[66] Shen F.F., Wu Q., Lin Z.R., et al. Effects of different interference orders of electroacupuncture and exercise therapy on the therapeutic effect of hemiplegia after stroke [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2008;28(10):711-713.

[67] Ouyang Q., Zhou W., Zhang C.M. The key of increasing the therapeutic effect of scalp acupuncture on hemiplegia due to stroke. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007;27(10):773-776.

[68] Han J.S. Electroacupuncture: an alternative to antidepressents for treating affective diseases? Int J Neurosci. 1986;29:79-92.

[69] Sawazaki K., Mukaino Y., Kinoshita F., et al. Acupuncture can reduce perceived pain, mood disturbances and medical expenses related to low back pain among factory employees. Ind Health. 2008;46(4):336-340.

[70] He J., Shen P.F. Clinical study on the therapeutic effect of acupuncture in the treatment of post-stroke depression. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2007;32(1):58-61.

[71] Molassiotis A., Sylt P., Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: A randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15(4):228-237.

[72] Khadilkar A., Phillips K., Jean N., et al. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for post-stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2006;13(2):1-269.

[73] Huang P., Liu M. Stroke and Parkinson’s Disease. Beijing: Peoples’ Medical Publishing House, 2007.

[74] Maclean W., Lyttleton J., Windstroke. Clinical Handbook of Internal Medicine. Sydney: University of Western Sydney Macarthur, 1998;624-654.

[75] Maciocia G. The Foundations of Chinese Medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1989.

[76] Beijing College. Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1980.

[77] Chan H.P.Y. Clinical trials of the treatment of stroke using various traditional acupuncture methods. Acupuncture for Stroke Rehabilitation. Boulder: Blue Poppy Press, 2006;27-32.

[78] Alexander D.N., Cen S., Sullivan K.J., et al. Effects of acupuncture treatment on poststroke motor recovery and physical function: a pilot study. American Society of Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2004;18(4):259-267.

[79] Fink M., Rollnik J., Bijak M., et al. Needle acupuncture in chronic poststroke leg spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):667-672.

[80] Park J., White A.R., James M.A., et al. Acupuncture for subacute stroke rehabilitation. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2026-2031.

[81] Zhang Z.H., Liu M., Asplund K., Li L. Acupuncture for acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:1-22., CD00317

[82] Bowsher D. Central post-stroke (‘thalamic syndrome’) and other central pains. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1999;16(4):593-597.

[83] Yen H.L., Chen W. An east–west approach to the management of central post-stroke pain. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:27-30.

[84] Zhou X.J., Chen T., Chen J.T. 75 infantile palsy children treated with acupuncture, acupressure and functional training. Chung Kuo Chung Hsi I Chieh Ho Tsa Chih. 1993;13(4):220-222.

[85] Wu Q., Chen H. The effect of acupuncture on improving the quality of life of cerebral palsy patients. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture. 2005;14(4):251.

[86] Mu R., Chen L., Liu L., et al. Combined acupuncture and functional exercises for infantile cerebral palsy in 45 cases. Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science. 2003;1(6):13-14.

[87] Watson P. Modulation of involuntary movements in cerebral palsy with acupuncture. Acupuncture Med. 2009:76-77.

[88] Dorsher P.T., Fleckenstein J. Trigger points and classical acupuncture points: part 3: relationships of myofascial referred pain patterns to acupuncture meridians. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Akupunktur. 2009;52(1):9-14.

[89] Dobkin B.H. Traumatic brain injury. The clinical science of neurologic rehabilitation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003;497-546.

[90] Campbell M. Acquired brain injury: trauma and pathology. In: Stokes M., editor. Physical management in neurological rehabilitation. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2004:103-124.

[91] De Silva M.J., Roberts I., Perel P., et al. Patient outcome after traumatic brain injury in high-, middle- and low-income countries: analysis of data on 8927 patients in 46 countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(2):452-458.

[92] RCP and BRSM. Rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: national clinical guidelines. Royal College of Physicians, 2003.

[93] Chen Y.X. Puncturing Shendao in treating hemiplegia following head injury. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture. 1997;8(3):293-294.

[94] He J., Wu B., Zhang Y. Acupuncture treatment for 15 cases of post-traumatic coma. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25(3):171-173.

[95] Donnellan C.P. Acupuncture for central pain affecting the ribcage following traumatic brain injury and rib fractures – a case report. Acupuncture In Medicine. Acupunct Med. 2006;24(3):129-133.