Acquired Anorectal Disorders

Perianal and Perirectal Abscess

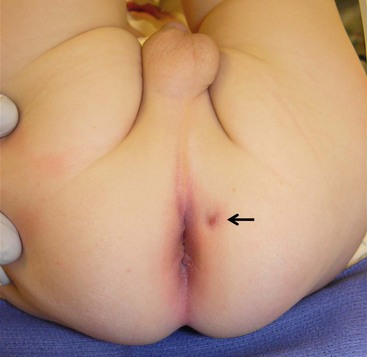

Perianal or perirectal abscesses are often encountered during infancy. The abscess typically presents as a fluctuant, tender mass in the perianal region (Fig. 37-1). A history of stool abnormalities is typically not elicited. Perianal abscesses are much more common in male infants and are infrequent in toddlers and older children.1 Crohn disease, immunodeficiency, glucose intolerance, and perianal trauma can be causative stimuli in the older child. It is unusual to find complex ischiorectal abscesses in children unless associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

FIGURE 37-1 Perianal abscesses are often seen in male infants. The abscess typically presents as a fluctuant, tender mass in the perianal region. Incision and drainage is the initial management of these abscesses.

For the infant, sitz baths are prescribed if the abscess does not appear to be fluctuant. Approximately one-third of abscesses thus treated resolve without recurrence.2 Approximately two-thirds require incision and drainage. Although drainage can be accomplished in the infant without general or topical anesthesia, we prefer a brief inhalational anesthetic to allow for adequate drainage and optimal patient comfort. Considerable debate exists with regard to making an effort to delineate a fistula at the time of abscess drainage, yet we prefer simple abscess drainage as the initial step.3,4 The patient begins sitz baths on the first postoperative day, and oral antibiotics are not needed once the abscess has been drained.

Fistula-In-Ano

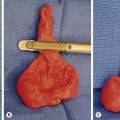

As many as 50% of perianal abscesses progress to a fistula-in-ano.5 The child is usually seen after two or more ‘flare ups’ of a perianal abscess that either continues to drain or forms a small pustule that ruptures, only to form again (Fig. 37-2).6 The fistula is commonly located lateral to the anus rather than in the midline. An intriguing theory has been suggested that fistula-in-ano results from infection in abnormally deep crypts that are under the influence of androgens. The fact that fistula-in-ano rarely follows a perianal abscess in female infants lends credence to this theory.7

FIGURE 37-2 As many as one-half of the perianal abscesses progress to a fistula-in-ano. In this photograph, the fistula is seen at 1 o’clock when the infant is in the lithotomy position.

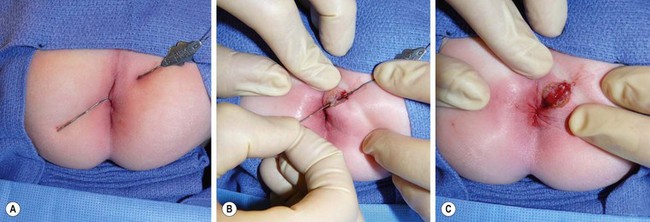

Our preferred operative technique for a fistula-in-ano is fistulotomy which is described within the caption of Figure 37-3. Following the procedure, we instruct the parents to place the infant in a sitz bath after each bowel movement, at least twice daily, and to separate the skin edges of the fistulotomy during bathing to promote healing by secondary intention. We reserve cryptectomy for patients with recurrence, which is rare after an adequate fistulotomy.

FIGURE 37-3 (A) At the time of operation, a small, fine, malleable probe is inserted through the fistula and can usually be gently advanced until it is visualized to exit the base of the involved crypt. (B) An incision is then made along the probe and is deepened through the superficial portion of the external sphincter. (C) After complete unroofing of the tract, the incision is usually left open, which may provide some distress on the part of the parents but usually does not cause much discomfort for the child.

Anal Fissure

An anal fissure commonly develops in a toddler whose diet changes from liquid to solid and whose stool consistency changes from soft to firm. A period of constipation results in a posterior midline tear in the anoderm below the mucocutaneous junction. The discomfort with defecation leads to further constipation, which aggravates the fissure and prevents healing. The diagnosis is made with a history of hematochezia, the child’s crying during bowel movements, and the recognition of a split in the anoderm. Operative interventions such as lateral internal sphincterotomy or fissurectomy are rarely necessary.8,9 We prefer sitz baths and an osmotic stool softener, such as polyethylene glycol, which usually results in healing.

For older children without evidence of IBD, topical 0.2% nitroglycerin ointment can be used. However, the collective evidence for utilizing topical glyceryl trinitrate suggests that this treatment is no better than placebo.10 Chemical sphincterotomy using Botulinum toxin is employed when nonoperative interventions have failed. We prefer a total of 25–50 units of Botulinum toxin A prepared in sterile saline. This volume is divided into four aliquots and injected into the sphincter complex in four circumferential quadrants.

An anal fissure in an older child or a teenager may be associated with Crohn disease.11 Immunomodulatory treatment of Crohn disease typically results in healing of the fissure.12,13 Topical application of tacrolimus ointment is a promising relatively new therapy.14 Internal sphincterotomy appears to be a relatively safe undertaking in this patient population, but only when local measures and immunomodulator therapy have failed.15

Anal Skin Tags, Hemorrhoids, and Other Perianal Vascular Lesions

A perianal skin tag is rarely an indication of other disease, although it may result from a healed fissure (Fig. 37-4). Although it is generally of no consequence, when large enough it can be bothersome and can affect adequate perianal hygiene. In these cases, local excision is reasonable.

FIGURE 37-4 This 1-year-old developed this anal skin tag secondary to constipation. Due to its size, it was excised.

Hemorrhoids are uncommon in the pediatric population, and rarely is operative therapy a necessary aspect of treatment. External hemorrhoids are located in the distal one-third of the anal canal and covered by anoderm. Symptoms from external hemorrhoids are generally due to thrombosis, and examination reveals a tender, bluish mass at the mucocutaneous junction (Fig. 37-5). Treatment consists of incision of the hemorrhoid and extrusion of the clot with subsequent sitz baths, dietary modification (fiber supplementation), and stool softeners. Internal hemorrhoids are extremely rare in children unless associated with portal hypertension. The treatment for bleeding from internal hemorrhoids due to portal hypertension should be aimed at decreasing portal pressure, either pharmacologically or surgically. In patients without portal hypertension, initial treatment of internal hemorrhoids should be focused on conservative measures such as the provision of stool bulking agents and topical treatment (sitz baths and topical pharmaceutical preparations). Rubber band ligation or operative hemorrhoidectomy is performed when conservative measures fail.

Rectal Prolapse

Rectal prolapse is a relatively common problem in young children and causes great distress to both child and parent. Prolapse can range from intermittent mucosal prolapse that reduces spontaneously to full-thickness prolapse, which often requires manual reduction. Regardless, prolapse should be reduced promptly to prevent vascular compromise. Rectal prolapse in children is likely precipitated by weakness of the pelvic levator musculature and a loose attachment of the rectal submucosa to the underlying muscularis. The latter often improves with time, whereas a weak and dilated pelvic floor may not.16 Straining during stooling, and long periods of sitting on the toilet, allows stretching of the pelvic diaphragm and other less well-defined rectal suspensory structures which results in prolapse.17 Up to 20% of cases of rectal prolapse diagnosed between 6 months and 3 years of age are associated with cystic fibrosis.18

The diagnosis is usually made by noting a rosette of mucosa when the child complains of discomfort while defecating (Fig. 37-6). Bleeding is occasionally noted, and rarely is it a source of significant disability. Unfortunately, it is uncommon for the child to be able to produce the prolapse in the examining room. We will ask the child to sit on the commode during an office visit in an attempt to demonstrate the prolapse. Often, it may be helpful to have the parents take a digital photograph during an episode so it can be viewed later at an office visit. Sometimes what appears to be rectal prolapse is an intussusception of the sigmoid colon.19 In these cases, an intact rectal suspension system exists but a dilated levator mechanism, coupled with a redundant sigmoid colon, allows for its intussusception. It is often difficult to differentiate between prolapse and intussusception clinically. Regardless, the entity must be reduced promptly to prevent vascular compromise.

FIGURE 37-6 This 2-year-old developed persistent rectal prolapse. The prolapse occurred several times daily and was not responsive to medical management. The child underwent submucosal sclerotherapy with 5% sodium morrhuate and the prolapse resolved.

Nonoperative treatment is the primary course of action in most cases. A change in defecation habits and provision of stool softeners may allow the pelvic musculature to resume its normal tone. We advocate that patients be restricted from spending prolonged periods of time on the commode. In addition, a child-specific commode or a step stool in front of an adult commode may eliminate straining-like behaviors. In patients who are identified with cystic fibrosis, enzymatic supplementation and improving malnutrition may be all that is required to eliminate episodes of prolapse.20

There are a number of operative approaches. Perianal cerclage tightens the anal outlet and prevents prolapse from recurring while the musculature of the pelvic floor re-establishes its normal anatomic relationship.21 The cerclage procedure is often effective, although one must be cautious to avoid making the cerclage too tight. This can be prevented by tying the cerclage over an appropriately sized Hegar dilator.22 Sclerotherapy with any number of compounds (30% saline, Deflux, 25% glucose, 5% sodium morrhuate) injected into the submucosal or retrorectal space produces an inflammatory response that theoretically prevents the rectum from sliding downward.23–27 We have found submucosal injection of 5% sodium morrhuate to be especially effective in children with mucosal prolapse unresponsive to nonoperative therapy. An open sclerosing procedure, in which the retrorectal space is developed and packed with gauze, is currently not routinely performed.28,29 Endorectal cauterization or mucosal stripping may be effective; however, there is little evidence that rectal prolapse is due to mucosal ‘overabundance,’ and we do not recommend this as primary surgical therapy.30,31

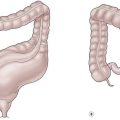

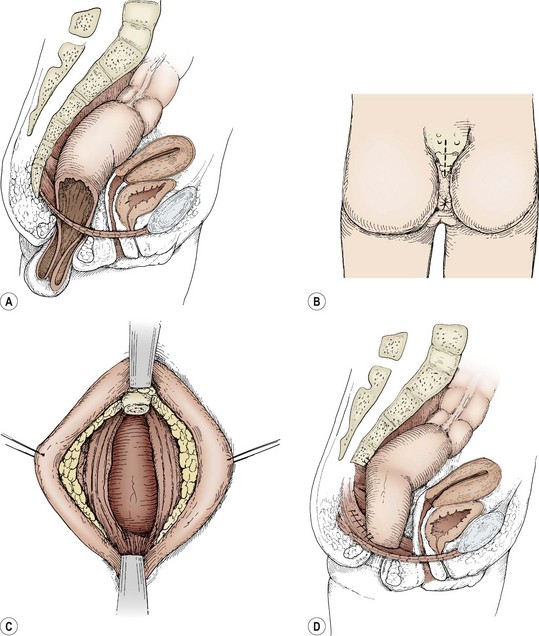

In patients with full-thickness prolapse, or for those who have failed nonoperative therapy, operative fixation techniques can be used. Transanal suture fixation of the rectum (Ekehorn rectopexy) has recently been used in a group of children with good success.32,33 Its benefit probably derives from the inflammation and adhesions that are produced by the mattress sutures. An extensive plication or reefing of the posterior rectal wall via a coccygectomy incision has been reported to have good results, but the morbid potential for a rectocutaneous fistula makes this a technique that we do not routinely employ.34 Laparoscopic rectopexy is an alternative to standard open rectopexy and is performed with two operating ports and a port for laparoscopic visualization.35,36 The rectum is mobilized and sutured to the periosteum of the sacral promontory in multiple locations with nonabsorbable suture. The operation has been successfully completed in children as young as 10 months of age, and results are encouraging. Open posterior rectopexy is yet another technique for rectal prolapse.37 Through a natal cleft incision, the coccyx is removed, the muscular hiatus is narrowed, and the rectum is suspended from the cut edge of the sacrum so that it cannot slide downward (Fig. 37-7). This maneuver immediately re-establishes the levator ani suspensory mechanism and narrows the anorectal hiatus. Successful resolution of rectal prolapse in 42/46 patients utilizing this technique over a 17-year period has been described.38

FIGURE 37-7 (A) A cut-away sagittal view illustrates the failure of the rectal suspensory mechanism to hold the rectum within the pelvis. (B) The posterior sagittal incision is depicted. (C) The coccyx has been removed and the posterior rectal wall exposed. (D) The pelvic diaphragm is closed posterior to the reduced rectum. The rectum is sutured laterally to the pelvic diaphragm. The rectum is further suspended from the cut edge of the sacrum. (A and D adapted from Ashcraft KW, Amoury RA, Holder TM. Levator repair and posterior suspension for rectal prolapse. J Pediatr Surg 1977;12:241–5; B and C from Ashcraft KW. Atlas of Pediatric Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994. p. 217.)

Rectal Trauma

Rectal trauma in pediatric patients generally occurs by one of two mechanisms. The first is from penetrating trauma after an accidental impalement injury or, occasionally, a gunshot (Fig. 37-8). The second, and more common, occurs as the result of sexual abuse. The most common clinical presentation is that of a chronic stellate laceration of the anus with edema (Fig. 37-9). Perianal condylomata are common sequelae in cases of sexual abuse. Careful questioning may reveal that a male member of the immediate family has penile condylomata. However, 25% of males who carry papillomavirus in the urethra have no external evidence of disease.39

FIGURE 37-8 This teenager sustained a gunshot wound to the buttocks with a suspected injury to the rectum. He underwent sigmoidoscopy followed by a diverting colostomy. Several days postoperatively, this contrast study was performed and revealed extravasation (arrow) from the rectal injury.

FIGURE 37-9 This male child was the victim of chronic sexual abuse and shows the typical stellate lacerations of the anal mucosa and skin.

The patient with an accidental injury to the anus is typically seen immediately after the incident. Sexual abuse is suspected when an inconsistent history of the mechanism of injury is elucidated or there is a delay in presentation. As with other forms of sexual abuse, difficulty is often encountered in obtaining an adequate history from the victim owing to fear, threats of retaliation, or guilt. Unexplained injuries to the rectum must be considered a manifestation of sexual abuse until proven otherwise, and should be investigated through the appropriate social service authorities.40–42

The child who has a traumatic rectal injury is usually difficult to examine. An impalement injury often requires rectal examination and/or sigmoidoscopy under general anesthesia (Fig. 37-10). This allows a complete assessment of the injury and also allows appropriate operative treatment if necessary. Photographs should be obtained to document the injury for medicolegal purposes. A retrograde urethrogram and/or voiding cystourethography should be obtained when there is suspicion of injury to the lower urinary tract.

FIGURE 37-10 This 14-year-old suffered a straddle injury after falling off a trampoline. He required examination under anesthesia. The perineal and rectal injuries were closed in layers without the need for colostomy.

Treatment of penetrating rectal injuries often requires a diverting colostomy.43 However, primary repair without fecal diversion can be performed safely in select cases.44,45 When in doubt, one should divert the fecal stream to avoid the consequences of perineal infection. In general, isolated intraperitoneal rectal injuries can be treated with primary repair. Inaccessible or severe distal extraperitoneal rectal injuries should be treated by fecal diversion and presacral drainage.46 Accessible injuries to the distal rectum and anal canal can be repaired with the intent of reapproximating the underlying sphincter muscle mechanism and the overlying mucosa. In the victim who is found to have an acute laceration extending up the rectal wall, it is rarely necessary to perform a diverting colostomy, because these lacerations are not usually full thickness. However, patients with full-thickness injury should be managed by repair and diverting colostomy. When present, treatment of condylomata depends on the extent of disease. Although small lesions may be responsive to repeated applications of topical agents such as podophyllin or imiquimod, more extensive lesions require excision. Intralesional interferon may be a useful adjunct for recurrent disease.47

References

1. Fitzgerald, RJ, Harding, B, Ryan, W. Fistula-in-ano in childhood: A congenital etiology. J Pediatr Surg. 1985; 20:80–81.

2. Rosen, NG, Gibbs, DL, Soffer, SZ, et al. The nonoperative management of fistula-in-ano. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35:938–939.

3. Murthi, GV, Okoye, BO, Spicer, RD, et al. Perianal abscess in childhood. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002; 18:689–691.

4. Stites, T, Lund, DP. Common anorectal problems. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007; 16:71–78.

5. Poenaru, D, Yazbeck, S. Anal fistula in infants: Etiology, features, management. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:1194–1195.

6. Ross, ST. Fistula in ano. Surg Clin North Am. 1988; 68:1417–1426.

7. al-Salem, AH, Laing, W, Talwalker, V. Fistula-in-ano in infancy and childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:436–438.

8. Cohen, A, Dehn, TC. Lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy for treatment of anal fissure in children. Br J Surg. 1995; 82:1341–1342.

9. Lambe, GF, Driver, CP, Morton, S, et al. Fissurectomy as a treatment for anal fissures in children. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000; 82:254–257.

10. Tankova, L, Yoncheva, K, Kovatchki, D, et al. Topical anal fissure treatment: Placebo-controlled study of mononitrate and trinitrate therapies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009; 24:461–464.

11. Sweeney, JL, Ritchie, JK, Nicholls, RJ. Anal fissure in Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1988; 75:56–57.

12. Buchmann, P, Keighley, MR, Allan, RN, et al. Natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease. Ten year follow-up: A plea for conservatism. Am J Surg. 1980; 140:642–644.

13. Strong, SA. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007; 16:185–193.

14. Hart, AL, Plamondon, S, Kamm, MA. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease: Exploratory randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007; 13:245–253.

15. Fleshner, PR, Schoetz, DJ, Jr., Roberts, PL, et al. Anal fissure in Crohn’s disease: A plea for aggressive management. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995; 38:1137–1143.

16. Severijnen, R, Festen, C, van der Staak, F, et al. Rectal prolapse in children. Neth J Surg. 1989; 41:149–151.

17. Corman, ML. Rectal prolapse in children. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985; 28:535–539.

18. Park, RW, Grand, RJ. Gastrointestinal manifestations of cystic fibrosis: A review. Gastroenterology. 1981; 81:1143–1161.

19. Theuerkauf, FJ, Jr., Beahrs, OH, Hill, JR. Rectal prolapse. Causation and surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1970; 171:819–835.

20. Shwachman, H, Redmond, A, Khaw, KT. Studies in cystic fibrosis. Report of 130 patients diagnosed under 3 months of age over a 20-year period. Pediatrics. 1970; 46:335–343.

21. Zempsky, WT, Rosenstein, BJ. The cause of rectal prolapse in children. Am J Dis Child. 1988; 142:338–339.

22. Touloukian, RJ. Anorectal Prolapse, Abscess, and Fissure. In: Ziegler MM, Azizkhan RG, Weber TR, eds. Operative Pediatric Surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003:735–738.

23. Abes, M, Sarihan, H. Injection sclerotherapy of rectal prolapse in children with 15 percent saline solution. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 14:100–102.

24. Chan, WK, Kay, SM, Laberge, JM, et al. Injection sclerotherapy in the treatment of rectal prolapse in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:255–258.

25. Fahmy, MA, Ezzelarab, S. Outcome of submucosal injection of different sclerosing materials for rectal prolapse in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004; 20:353–356.

26. Shah, A, Parikh, D, Jawaheer, G, et al. Persistent rectal prolapse in children: Sclerotherapy and surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005; 21:270–273.

27. Zganjer, M, Cizmic, A, Cigit, I, et al. Treatment of rectal prolapse in children with cow milk injection sclerotherapy: 30-year experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2008; 14:737–740.

28. Balde, I, Mbumbe-King, A, Vinand, P. [The Lockhart-Mummery technique in the treatment of the total rectal prolapse among children. Concerning 25 cases (author’s transl)]. Chir Pediatr. 1979; 20:375–377.

29. Scheye, T, Marouby, D, Vanneuville, G. [Total rectal prolapse in children. Modified Lockhart-Mummery operation]. Presse Med. 1987; 16:123–124.

30. El-Sibai, O, Shafik, AA. Cauterization-plication operation in the treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2002; 6:51–54.

31. Hight, DW, Hertzler, JH, Philippart, AI, et al. Linear cauterization for the treatment of rectal prolapse in infants and children. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982; 154:400–402.

32. Sander, S, Vural, O, Unal, M. Management of rectal prolapse in children: Ekehorn’s rectosacropexy. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999; 15:111–114.

33. Schepens, MA, Verhelst, AA. Reappraisal of Ekehorn’s rectopexy in the management of rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:1494–1497.

34. Tsugawa, C, Matsumoto, Y, Nishijima, E, et al. Posterior plication of the rectum for rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995; 30:692–693.

35. Koivusalo, A, Pakarinen, M, Rintala, R. Laparoscopic suture rectopexy in the treatment of persisting rectal prolapse in children: A preliminary report. Surg Endosc. 2006; 20:960–963.

36. Tsugawa, K, Sue, K, Koyanagi, N, et al. Laparoscopic rectopexy for recurrent rectal prolapse: A safe and simple procedure without a mesh prosthesis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002; 49:1549–1551.

37. Ashcraft, K. Acquired Anorectal Disorders. In Ashcraft K, Holcomb GI, Murphy J, eds.: Pediatric Surgery, 4th ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005.

38. Ashcraft, KW, Amoury, RA, Holder, TM. Levator repair and posterior suspension for rectal prolapse. J Pediatr Surg. 1977; 12:241–245.

39. Rosemberg, SK, Husain, M, Herman, GE, et al. Sexually transmitted papillomaviral infection in the male: VI. Simultaneous urethral cytology-ViraPap testing of male consorts of women with genital human papillomaviral infection. Urology. 1990; 36:38–41.

40. Adams, JA. Medical evaluation of suspected child sexual abuse: It’s time for standardized training, referral centers, and routine peer review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999; 153:1121–1122.

41. Geist, RF. Sexually related trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1988; 6:439–466.

42. Kadish, HA, Schunk, JE, Britton, H. Pediatric male rectal and genital trauma: Accidental and nonaccidental injuries. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998; 14:95–98.

43. Haut, ER, Nance, ML, Keller, MS, et al. Management of penetrating colon and rectal injuries in the pediatric patient. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004; 47:1526–1532.

44. Bonnard, A, Zamakhshary, M, Wales, PW. Outcomes and management of rectal injuries in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007; 23:1071–1076.

45. Levine, JH, Longo, WE, Pruitt, C, et al. Management of selected rectal injuries by primary repair. Am J Surg. 1996; 172:575–579.

46. Weinberg, JA, Fabian, TC, Magnotti, LJ, et al. Penetrating rectal trauma: Management by anatomic distinction improves outcome. J Trauma. 2006; 60:508–514.

47. Congilosi, SM, Madoff, RD. Current therapy for recurrent and extensive anal warts. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995; 38:1101–1107.